“I don’t believe in ghosts,” Brynn announced. She fingered the dress of the doll Price had given her, then placed it on the windowsill. The three siblings sat in their pajamas in the library. Brynn was in her bed with her sheets drawn up over her lap. She wore a nightgown that was too small for her, pulling across her shoulders and exposing her twig wrists. “It just doesn’t make sense. All the time the world has been here, all those people, we’d be overrun with them.”

“Did someone tell you there were ghosts here?” Price asked.

“Ephraim said it looked haunted.”

Ephraim had been examining his toes, but he snapped his head up when she said that. “I didn’t mean I actually thought it was haunted. I just said that it looked that way. Like if this were a movie, this would be a haunted house. But not in real life.”

Brynn shrugged. “I was just pointing out that it’s not possible.”

“You’re right,” Price said. “But if you do get scared, all you have to do is think about your breathing. You just breathe in and out really slowly, through your mouth. That’s what Coach always has us do for a big race and it works every time. Sometimes when I’m really excited the night before, I do it while I’m lying in bed and it puts me right to sleep. Okay?”

“Okay,” Brynn agreed.

A gust of wind picked up and shook the panes of the window. It sounded like someone knocking to get in. Brynn took a deep breath in and exhaled.

“Good,” Price said. “Now listen. I think we’re going to have to start acting more grown-up. Mom’s under a lot of stress and we need to help her out as best we can.”

He didn’t look at Ephraim, but the words felt like tiny little arrows pricking him all over his body. Ephraim shuddered thinking of that night’s dinner. He’d asked their mother how long they’d be staying. When she said she wasn’t sure, he demanded, “How about a ballpark? A few weeks or months or what?” Ephraim didn’t know why he’d pushed his fragile mother. He was angry. Angry about being ripped away from his if not happy then stable existence back in Cambridge. Angry that his dad was not at the table, but instead sat silent in the bedroom upstairs. None of this was his mother’s fault, he knew, but he couldn’t seem to stop himself.

Then things had gotten worse. “We’ll be here long enough for you to attend school,” she had told them. “You’ll start tomorrow. The caretaker stopped by earlier and we arranged for him to pick you up and drive you in.”

Ephraim shoveled his spaghetti into his mouth, fuming at this latest development.

“I’ve never started a new school before,” Brynn said.

Their mom reached out and ruffled her hair. “You’ll do just fine, Brynn. I’m not worried about you at all.” Her glance quickly darted to Ephraim, then back down at her plate.

“Do you think they have a nice library?” Brynn asked.

“I’m sure they have a lovely library,” their mother said.

Ephraim snorted. He imagined a room full of dusty old books, with a librarian who wore a bun and glasses slipping down her pointy nose. It would be nothing like the library at their school in Boston, which was sunny and full of new books and computers.

“We’ll make it work, Mom,” Price said. Which was easy for Price to say.

In the library of the Water Castle, Price continued taking on the role of head of household. Ephraim wanted to be angry—who had made Price boss?—but it wasn’t like he was about to step up. “We each need to pitch in more,” Price said. “We need to do the dishes and maybe make dinner from time to time. Whatever we can to make life easier for Mom. I can bike into town whenever we need anything, but you guys will need to help around here.”

Ephraim walked over to the large telescope by the window. When he looked through the eyepiece, he saw that the glass on the far end was cracked.

Maybe Price had the right idea, he told himself. Maybe this would be his chance to make things work. Sure he’d never been anything more than mediocre back in Boston, but it was all relative. Compared to the kids in this small, middle-of-nowhere town, he would no doubt seem like an intellectual superstar. Coming from the city, he’d be far more sophisticated, too. Maybe this was just the chance he needed to reinvent himself. For however long they’d be there, he could be a different guy. A cool guy. A smart guy. A guy with lots of friends.

“Okay,” Brynn said. “I can keep things organized. I can make the shopping lists, too. Mom always forgets them at home anyway, and Dad just draws pictures when it’s his turn to do the shopping.”

Ephraim was in a reverie about the potential for newfound popularity when he realized they were both staring at him. “I’ll help out, too,” he said. “Somehow.”

“Good,” Price said. “Now I suggest we all go to sleep. It’s been a long day, and tomorrow will be another long one.”

He sounded like a person trying on his father’s clothes, but Ephraim and Brynn both nodded, and Price and Ephraim left for their individual rooms.

The three had always lived in the city, in a large home by city standards, but still piled on top of one another. Their mother, too, had grown up in a townhouse on Beacon Hill. Only their father had ever lived in the country. The siblings were used to the noise of cars, sirens, and most of all, each other. Spread out about the house as they were, no one felt at ease.

It did not help that everything was different, even the little things—especially the little things. The light switches were two round buttons, rather than an up-down switch. The sinks had one tap for cold, one for hot, and the stopper was labeled, in small script, waste. The carpets were threadbare, as if centuries of feet had carried the wool away with them. Each room had a fireplace with a stack of logs, ready to burn, along with giant mirrors, sconces on the walls, and beds so high even Price needed a stool to climb in.

It was not home.

It might have felt like an adventure if they were there for another reason, but none of them could forget why they had traveled to this giant house.

Price did ten sets of push-ups, then lay in bed and concentrated on regulating his breathing and pulse, just like he’d told the others to do. The first night in the house, he was able to put himself to sleep. Brynn removed stacks of books and placed them around the bed that Price and Ephraim had carried down from the third floor. She sat against the rattling windows of the library, reading the books with a headlamp strapped to her forehead.

Ephraim tried to do as Price had said. He closed his eyes and focused on breathing in and out, but before he knew it his eyes were wide open and his mind was racing. He was stuck in this town, in this creepy house, for an indefinite amount of time. He was going to have to start at a new school. And, of course, he could not forget that his father had had some sort of brain malfunction that kept him from speaking, reacting, and, Ephraim feared, feeling and remembering.

Ephraim got out of bed and went to the window. The moon, thin to the point of being barely visible, hung over the river. Though the light was dim, Ephraim made out a cluster of bats on the opposite shore. He shifted his gaze to the grounds of the house. He could make out shapes but wasn’t sure what they were—bushes, statues, walls.

There were two large oaks, and from each hung a swing. One of them swung back and forth, while the other was dead still. He wondered who had put them there and who had used them. It seemed inconceivable to him that a family had lived here.

He heard the humming—like a piano hitting one note and holding it for an impossibly long time. Below it was a sort of skittering noise. Ephraim was normally not the type of boy who investigated strange sounds in the night, but he figured if some sort of violence befell him, at least he wouldn’t have to go to school the next day.

The sound seemed to be coming from the far end of the house. He walked down the hall with his hands trailing along the textured wallpaper. At the end of the hall was a large window that overlooked the driveway up to the house, and he could almost imagine the people who had lived here before him standing where he stood: waiting, surveying.

The sound was definitely louder here, and higher pitched—one key up on the piano. He ran his hands along the wall, checking for vibrations. He had about given up when he noticed a blue glow. It seemed to be all around the house, growing brighter and brighter. He leaned against the window, his palm flat against the cool glass, turning his head from side to side to try to find the source of the glow. Just when he determined that it seemed to be coming from up above, there was a flash of light bright enough to blind him. The whole world seemed to turn blue. Ephraim’s eyes burned and he blinked until he could see again.

The humming subsided. It was still there, but barely discernible, and the skittering was gone completely. His vision glowed around the edges with the memory of the flash. He stood and waited. Waited. Nothing happened. He just stared out the window. Beyond the driveway was the town. A smattering of lights remained lit. He kept waiting for another flash, and when it didn’t come he wondered if he had imagined the whole thing, or if it was some trick of the eye.

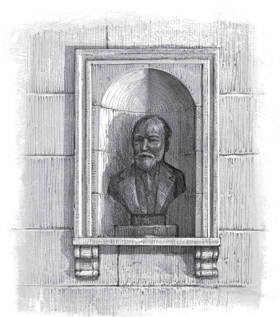

Either way, he was finally starting to feel tired. He started back down the hall and stopped at a small alcove that held, on a pedestal, a bust sculpted out of bronze. He leaned in to read the inscription: ORLANDO PRIAM APPLEDORE, KEEPER OF THE FLAME. The statue was dusty, so he blew on it. The dust sparkled in the scant light. It was a very lifelike sculpture, especially considering it was made of bronze. The eyes were closed, but Orlando seemed to be lost in thought, as if he might open his eyes at any moment and reveal his grand idea.

“Well, Orlando,” Ephraim said softly. “I hope you don’t mind us being in your house. It’s not exactly where I want to be.”

Orlando had no reply.