Casting is an important component of fly fishing, but as you will learn while progressing through the sport, it is not the most important. That statement may come as a surprise, but in fact, the selection of a fly, where the fly is placed, how the fly operates while on or in the water—all these things take precedence over the casting operation. Fly casting is often overemphasized to the point of intimidating the beginning angler. Casting myths are numerous and often perpetuated by those fishermen who themselves have not mastered all aspects of the sport.

For many years, if you could cast a fly you were thought to be an expert. Little attention was paid to whether you caught any fish; that was more or less assumed. Each year I watch fly fishermen, dressed to the nines, casting a beautiful line with few results. What fish these “around the bend fishermen” manage to catch are mysteriously taken in places too remote and rugged for others to document.

To put it plainly, the correlation between catching fish and your ability to cast a line is minimal. Many practitioners will tell a novice that fly casting is just too hard to learn. Nonsense! Practice will make you a better caster, but even without practice, most people, in a very short time, can learn to cast a fly well enough to catch fish.

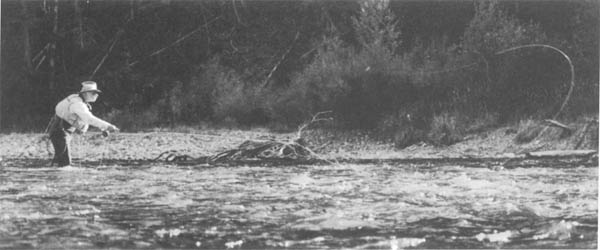

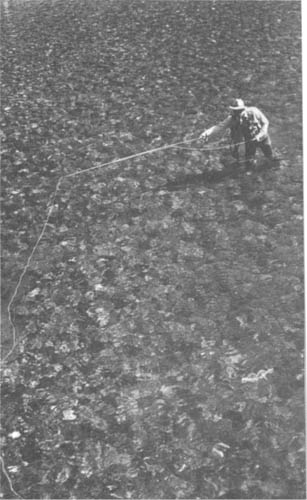

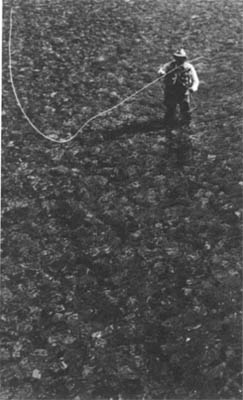

Another myth believed by many beginners is that you must cast great distances before you’re able to catch fish. In fact, most fish taken on a fly are hooked anywhere from ten to 25 feet from the angler, not the 80 or 100 feet that some anglers would have you believe. Every year, without fail, I have fishermen tell me how they made a 90-foot cast, dropping a dry fly within a circle the size of a teacup and taking the 20-inch trout that was quietly sipping naturals (that is, natural insects) off the surface. To make the story more interesting, the storyteller will sometimes throw in a 20-mile-per-hour cross-wind. In actuality, even if your hand-eye coordination was exceptional, the vast amount of slack line on the water would make setting the hook extremely difficult at that distance. No, sorry: If a fish is caught at 90 feet, more than likely the fish was responsible for the accident, not the long-distance caster.

Anglers, even professional instructors, all have their egos and would like you to believe there is only one way to cast—their way. Such is not the case. Granted, there are certain points and functions that should be learned and adhered to, but because people have different physiques and abilities, everyone will develop his own casting style. The same point applies to any sport. For example, all professional golfers have slightly different swings from each other, but all, when they hit the ball, apply the same basic principles. Adapting our unique characteristics to basic principles is the key to successful fly casting just as it is to successful golf.

The function of fly casting is to get the fly from point A to point B as efficiently as possible. It is only a means to an end and should be looked upon as just that. Our intent is to catch fish, not to impress them or other people with the beauty of the cast. And don’t think for a second that a fish is going to say, “That was a beautiful tight loop, Mr. Jones; therefore, I will take your fly.”

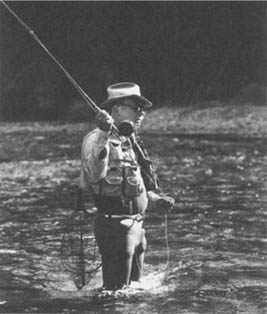

Fly casting requires little or no strength. It is the flexing and reflexing, often referred to as the loading and unloading of the rod, that makes the line work. Because strength is not a requirement for successful casting, many women and children often acquire the techniques more readily than beginning males, since they don’t try to muscle (or “macho”) the rod. They let the rod do the work, systematically using the hands, wrist, and arm to set the flexing and reflexing action of the rod in motion.

Fly rod function is analogous to pole-vaulting. The vaulter plants the pole, and his own body weight (plus momentum) loads the vaulting pole with energy. However, it is not his strength that lifts him up and over the bar. No, it is the release of that energy along the flexible shaft that drives him up and over. The same thing happens with a fly rod: The weight of the line loads the rod, and the movement of the arm and the flick of the wrist set the rod in motion, delivering the line.

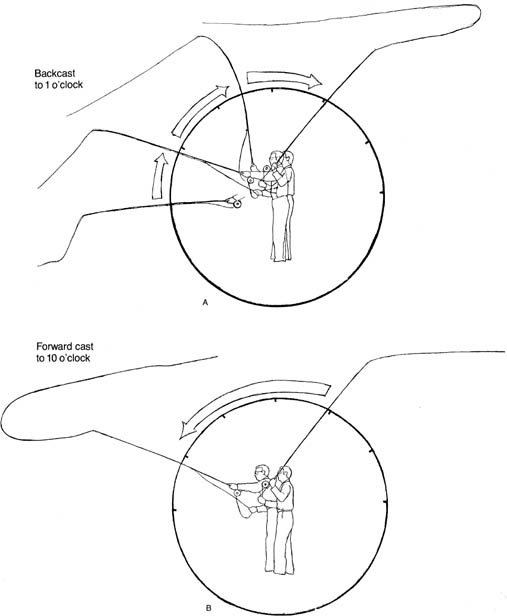

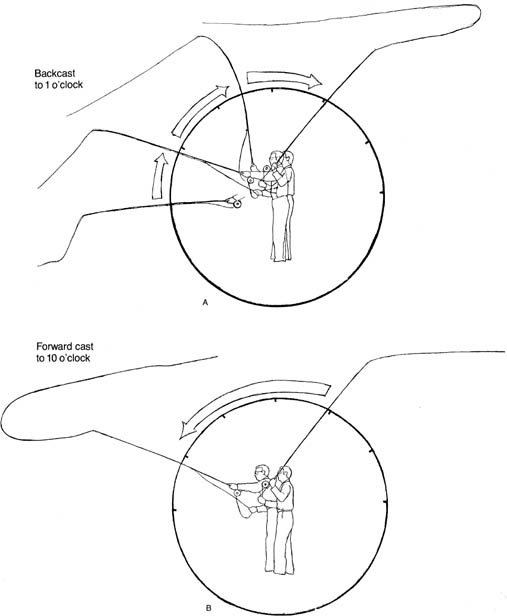

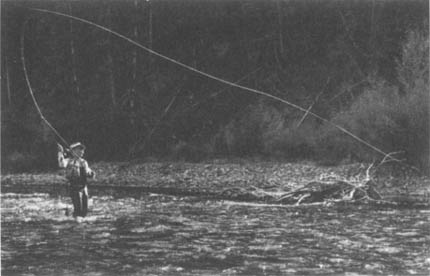

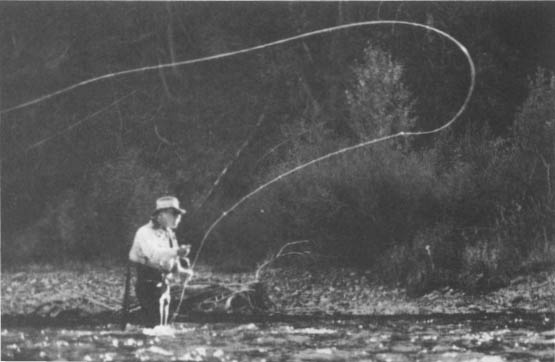

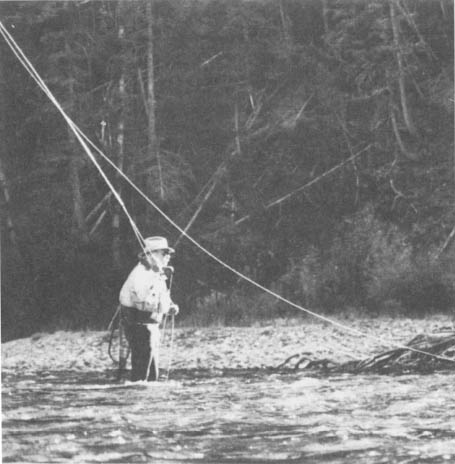

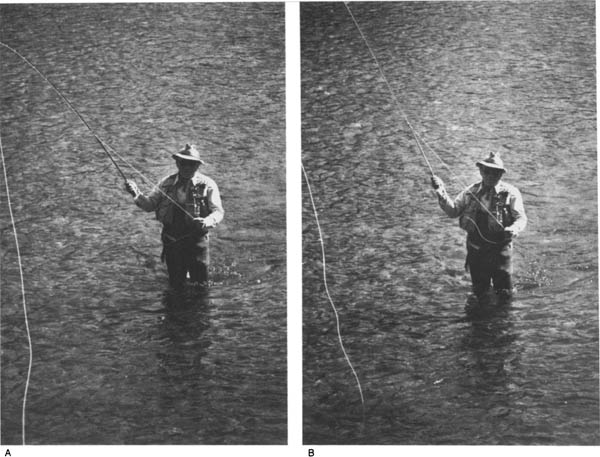

The basic fly cast consists of a backcast and a forward cast. The parameters of these motions have traditionally been taught as related to the hand positions on a clock, and this is still a good way of thinking about it. The backcast is started with the rod in the nine o’clock position, ending at one o’clock. The forward cast starts at one o’clock and ends at ten o’clock.

The backcast starts with the rod at the nine o’clock position, ending at one o’clock (A). The forward cast starts at the one o’clock position, ending at ten o’clock (B).

It is important to think of the cast in these terms, for the beginning caster needs to know what position his rod should be in throughout the cast.

Before you begin to practice your fly casting, choose a place without obstructions such as trees, shrubs, fences, or buildings. Obviously, a pond would be ideal, but a lawn, a swimming pool, or an actual river will work as well. Avoid a practice location that is on dirt or concrete pavement, for damage to the fly line can occur. I also recommend not using an actual fly with a hook, for it can become an eye-injuring weapon, certainly in the hands of a beginner. All that is needed to simulate a fly is a small piece of yarn, of the approximate weight of a fly, tied to the end of a leader. This will aid not only in turning over the leader when cast, but also in your developing some degree of accuracy.

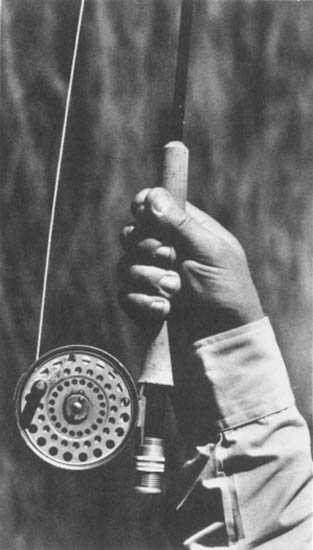

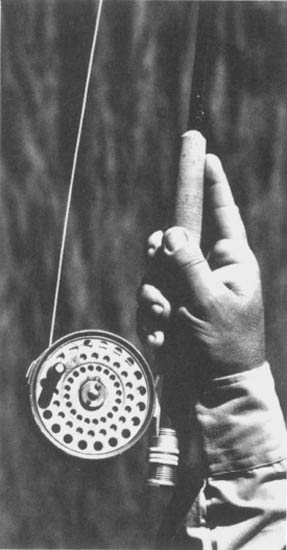

To start, pick up the rod and grip it with the thumb extended on top of the handle. If this feels uncomfortable, a simple baseball grip can also be used. There are some who extend their index finger down the rod grip, but I have found that after a day of casting or of handling very big rods, the index finger and hand will get fatigued. To avoid this, get in the habit of extending the thumb.

Before you start the backcast, strip off from the reel and extend through the guides approximately 20 feet of fly line. If you are right-handed, hold the line in your left hand tightly but comfortably, at about waist level. When first learning to fly cast, don’t get in the habit, although many do it, of gripping the fly line itself in the rod hand, for this position is improper in actual fishing and casting situations. Holding the line in the opposite hand is also more efficient; you can add more line to the cast simply by loosening the grip of the line itself in your hand.

The term “backcast” is to some extent misleading. It implies that the beginning portion of the cast goes directly back. In reality, you not only go back, but you actually lift the rod as well. Consequently, I call this portion of the cast the “up and back cast.”

With ten to 15 feet of line extending from the rod tip, place the rod in the nine o’clock position. As you slowly raise the rod, reaching the ten o’clock position, the weight and tension of the line will cause the rod to load, or flex. Upon reaching ten o’clock apply the “power stroke” (a term I use lightly) or quick wrist flick, which will activate the rod tip and start the line up and behind you. This stroke is stopped at about 12 o’clock, at which point you lock your wrist and, while the line uncoils behind you, drift your arm and rod to the one o’clock position. With the rod in the one o’clock position, you have reached the most critical point for a begining caster, because it is here that the most common mistake is made: the tendency of the beginner to break his wrist, going beyond the one o’clock position. Some experienced anglers can get away with a wrist break, but for a novice it means trouble, allowing the line to hit the ground and/or not letting the line extend above and behind you.

Correct grip.

The baseball grip (also correct).

A not-recommended grip.

To avoid breaking the wrist past one o’clock, novice fly casters were once taught to keep the arm close to the body. In fact, it was recommended that something breakable and valuable, but thin—like a full pint of whisky—be held under the armpit while the cast was in motion to properly motivate the learner. Today, however, we teach that the arm is a mere extension of the rod, which gives casting a more fluid arm movement. If you have trouble finding one o’clock with the rod, try 12; if that doesn’t work, try 11. Slowly you will find the right spot at which to stop your arm movement.

(Note: All rod positions in the photographs are the mirror image of clock positions mentioned in the captions. Thus, when the rod is at three o’clock in the photograph, think nine o’clock; when the rod is at eleven o’clock, think one o’clock, etc.)

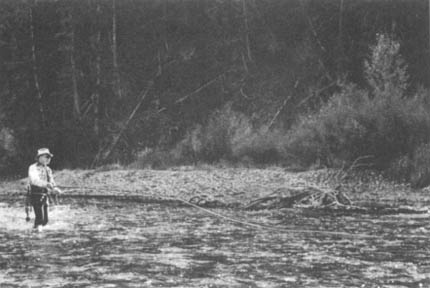

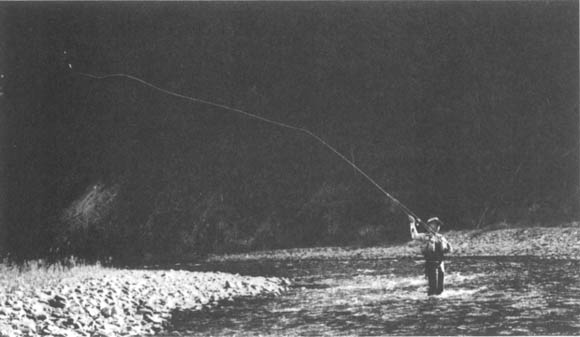

Before the backcast begins, the rod should be at the nine o’clock position, with 20 feet of line extended (A).

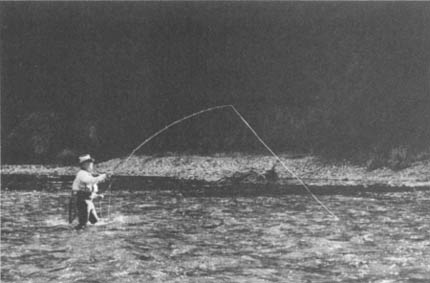

To begin the backcast, lift the rod to the ten o’clock position (B). This causes the road to begin flexing, or “loading.”

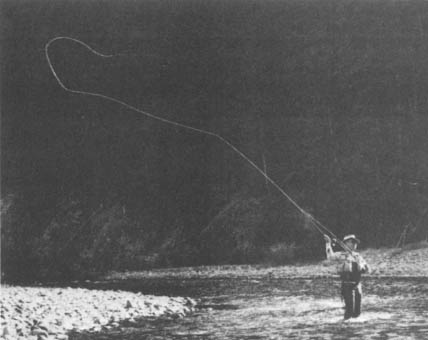

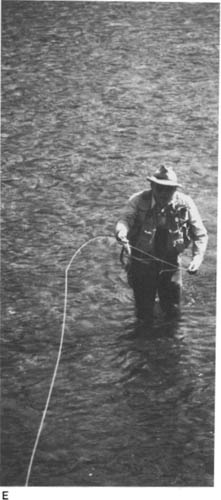

As the line travels backward, let the arm and rod drift back approximately to the one o’clock position (E).

When the rod reaches the one o’clock position, the wrist should be locked. At all costs, avoid breaking the wrist beyond this position (F).

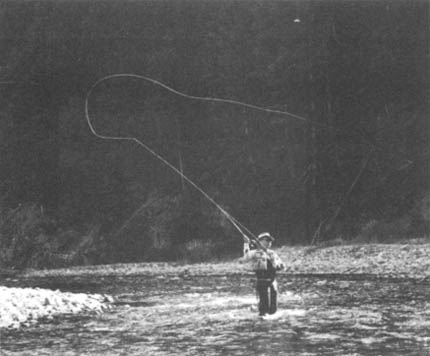

Upon reaching the ten o’clock position, apply the power stroke by quickly flicking the wrist and stopping at 11:30 (C). Note how the rod attains a fully loaded position.

After you halt the power stroke, the rod quickly unloads or reflexes (D). This causes the line to be driven backwards. Remember: It is the rod’s loading and unloading action that makes the cast work, not the strength of the caster.

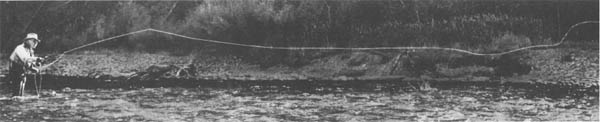

At the end of the backcast, the line should be fully extended behind you (G).

Good rod position at the end of the backcast.

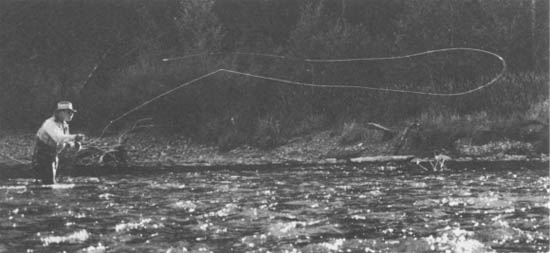

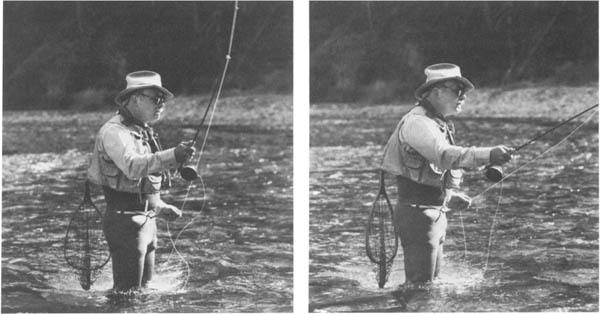

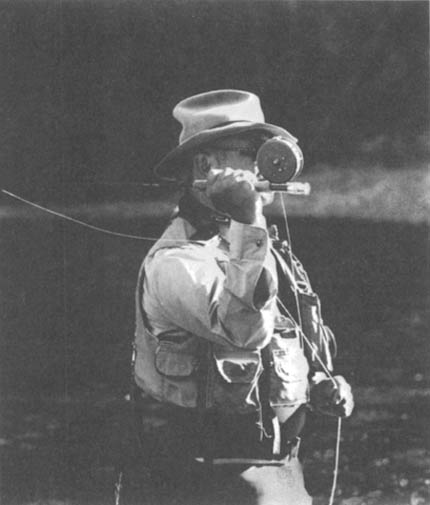

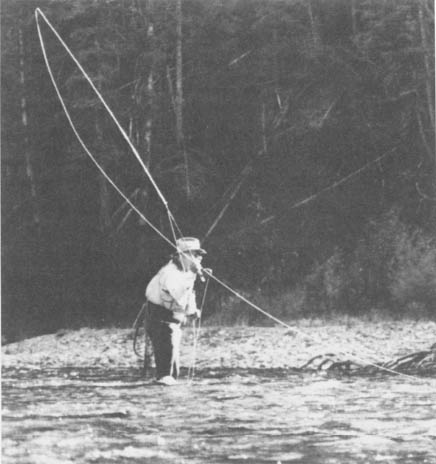

At one o’clock, hesitate slightly, allowing the line to completely lay out behind you. When the line reaches its full extension and before it begins to drop down below the plane of the rod tip, you should begin the forward cast. Don’t wait too long, for letting the line drop too low causes additional problems. When to start the forward movement of the rod is a matter of timing and feel. A good way to learn this important maneuver is to turn slightly around and look for the fully extended line. Once you learn the proper timing, however, you should stop “peeking” and rely on your feel of the rod either tugging or reloading. A tug at one o’clock means the weight of the line is reflexing or reloading the rod, preparing it for the forward cast.

The most common mistake the inexperienced caster makes on starting the forward cast is flicking the wrist from one o’clock in an effort to get the line forward. Don’t do it. Instead, start the forward movement by driving or pushing the rod forward while maintaining the rod in the one o’clock position. Some people call this first forward cast movement the “punch.” The rod has not moved from the one o’clock position—it has only been driven from the shoulder to a point out in front of us. What this very important movement does is load and flex the rod and help straighten out the line behind you.

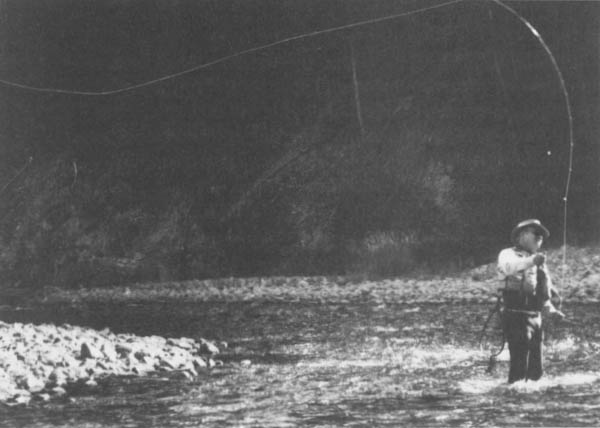

At the instant the line is fully extended behind you, begin the forward cast. You do this not by flicking the wrist forward, but by driving, or punching, the rod forward (A). This driving or punching action further straightens the line and starts the rod-loading process for the forward cast.

With the rod fully loaded (flexed) and in front of you, flick your wrist forward quickly to send the line on its forward flight (B).

After flicking the wrist forward, stop the rod at the ten o’clock position (C). Again, it is the unloading of the flexed rod that makes the cast work, not the strength of the caster.

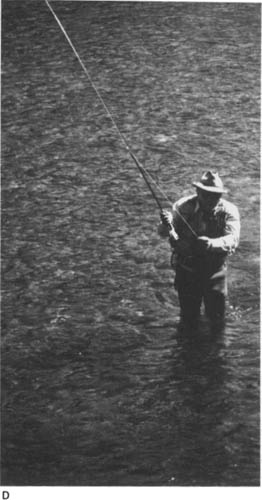

As the line begins to travel forward, the rod should remain at ten o’clock (D).

For line control and accuracy, the loop of the fly line should be tight and even (E). Loop tightness is determined by how quickly you flick your wrist. A slow flick opens the line, creating a wider loop.

As the line approaches its target (F), note that the rod remains at ten o’clock. The rod should never touch the water.

The line now extends fully (G) . . .

. . . and falls to water’s surface (H). Note that the rod remains at the ten o’clock position.

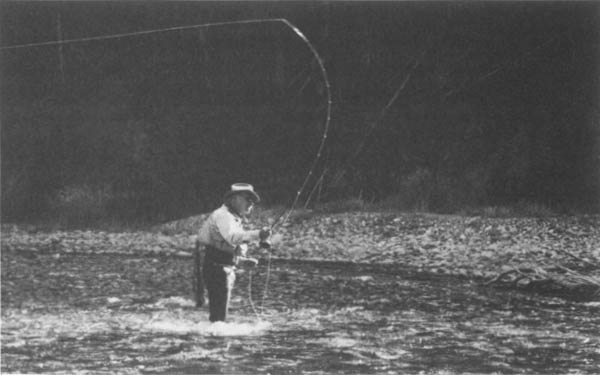

The drive, or punch, is perhaps the most important part of the forward cast. With the rod at one o’clock (A), do not flick the wrist, but first punch, or drive, the arm forward (B), until the rod is slightly in front of you. Then, and only then, do you flick your wrist forward (C), initiating the forward cast.

Once the rod and hand are slightly in front of you, flick your wrist, which unloads (unflexes) the rod, causing the line to be driven forward. Stop the arm and wrist flick at ten o’clock, allowing the line to fully extend and drop to the water as a complete unit. Do not bring the rod to nine o’clock, or the line will hit the water with a disturbing splash.

As you drive the rod forward on the forward cast, it is important to drive for a point on the horizon. Do not drive upward for the sky, nor downward for the water. If the line’s horizontal plane is thrown at too vertical an angle, the line, when extended, will pile back on the water, on top of itself. Guides call this mistake a bull’s-eye cast, the line making rings around itself and the fly falling in the middle. The line should fully extend out, then drop as a unit, and of its own accord, to the water.

As the line moves backward on the backcast and, most important, forward on the forward cast, your objective is to achieve a tight loop with the line. Tight loops give greater accuracy and also slice through high winds with greater efficiency. Tight loops are directly related to how quickly—not powerfully—you flick your wrist to actuate the rod tip (literally, to put it into mechanical motion). If on the forward cast you turn the wrist over slowly, the rod tip will unflex slowly, causing the line to roll out in a wide loop. If the wrist is turned over quickly, the rod tip actuates quickly, providing the desired tight loop.

It is important to note that fly casting, like any other mechanical sport, requires practice. Casting efficiency does not come automatically and does require a certain amount of work. But regardless of your casting abilities, there are certain mistakes and problems that do develop time and again to casters at all levels. The following is a list of the most common casting problems encountered.

If your backcast does not extend the line fully, undoubtedly you are not applying enough power, or snap, on the backcast motion to drive the line back. Remember, the rod is not a fairy wand; you can’t baby it and you must use some authority. Apply more power and snap when lifting the line off the water.

Snapping the line is caused by not allowing the line to extend fully outwards on the backcast. Still uncoiling when the forward cast is started, the line snaps, or pops, like a bullwhip. To avoid line snapping, allow the line to extend completely by hesitating a bit longer before starting the forward cast.

Catching ground and bushes behind you is a common problem for the beginner. The cause is either waiting too long at the end of the backcast, allowing the line to fall, or, as in most cases, allowing the rod to travel past the one o’clock position, a consequence of breaking your wrist.

To correct the first problem, shorten your delay in starting the forward cast. If you are breaking your wrist—the most common mistake—you should pay attention to where your rod is positioned at the end of the backcast. If visualizing the rod at one o’clock is difficult, try thinking of the rod position at 12 o’clock, or perpendicular to the ground.

Breaking the wrist, or allowing the rod to go far beyond the one o’clock position, is the beginning caster’s single most common mistake.

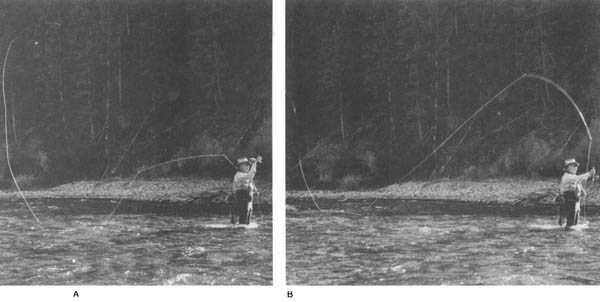

Breaking the wrist on the backcast initiates a host of problems. First, the line fails to extend fully, instead hitting the water behind you (A). Second, the line is not straight for the forward cast (B), resulting in a cast that does not drive out smartly in a tight loop (C), but rather, dies and falls to the water in a heap (D).

When the line has been driven toward the sky rather than toward the horizon, the line piles up on itself. Your angle of attack is wrong. Also, when starting your forward cast, you’re probably flicking your wrist immediately, rather than driving or punching the rod forward before snapping the wrist. Again, the line should be driven to a position on the horizon and allowed to drop to the water as a unit.

When the loops of your forward cast become very wide, or open, accuracy eludes you. The cause of wide loops lies in the quickness with which the wrist is snapped on the forward cast. To rectify the problem and create tight loops, simply snap the wrist quicker; don’t roll the wrist.

Hooking your fly on the line on the forward cast is a very common problem. Overpowering the rod—applying more strength and power than the rod flex can handle—is the most common cause. The result is a delayed reaction. To fix this, ease up on your power stroke. Also, chances are you have not driven or punched the rod forward from the one o’clock position. Driving—punching forward—is a must if the rod and line are to work well together.

Line splash disturbs fish, which never helps the fisherman. In most cases, you have not stopped the rod at ten o’clock during the forward cast, allowing the line to fall of its own accord. The rod tip touches the water, causing the line to crash upon the surface. To correct this, halt the forward cast at ten o’clock, allowing the line to extend fully and fall gently as a unit to the water.

The beginning caster should learn to cast in a straight up-and-down motion, not sidearm. Greater accuracy of fly presentation will result. There will be occasions, because of low-hanging shrubbery, when a side cast is necessary, but still the basic components of the cast remain the same. The clock face is still the reference point: The cast begins at nine, stops at one and comes back to ten—all we have done is laid the clock on its side.

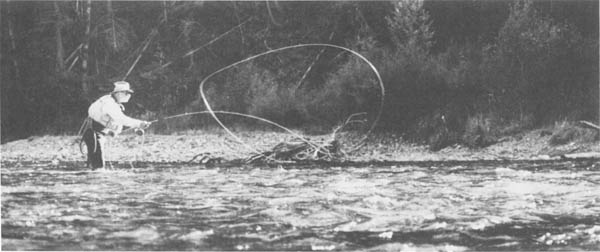

The roll cast is very useful and practical for all anglers of all abilities. It has many applications but is most often used when an angler has a large obstruction directly behind him, making a normal backcast impossible. The roll cast is easy to do, so much so that some of my beginning students have asked why they can’t use the roll cast instead of the normal cast.

To start, lay 15 or 20 feet of fly line on the water. It is best to try the roll cast on water, as water creates sufficient tension for the line to operate efficiently. Slowly raise the rod until it reaches the one o’clock position and then stop. Remember, you can’t make a backcast. The line should now be to the outside of the rod and a portion of the line should also be lying on the water. After line and rod have come to a complete stop, drive the rod forward and flick the wrist. The line will roll up and out.

The basic roll cast has multiple uses. The roll cast pickup, for example, is used to take the fly off the water and start the normal cast. After making a normal roll cast without letting the fly and line hit the water on the forward roll, start the backcast when the fly and line are in the air.

You can also change direction with the roll cast. Because streams have current, the fly will eventually end up below you. To get the fly and line upstream or into a more favorable casting position, roll the rod in the direction you wish to go and you will find that the line will follow the rod. This can be done either to the right or to the left. Remember, the basic roll cast technique still applies.

To start the roll cast, allow 15 to 20 feet of line to lay in front of you (A).

Slowly lift the rod to the one o’clock position, allowing the fly line to hang both behind and to the outside of the rod. When the rod reaches the one o’clock position, bring it to a complete but momentary stop (B).

With the rod driven forward, the line begins its rollout (E),

To start the forward cast, first drive, or punch the rod forward, hard, then flick the wrist. This starts the line forward (C).

The line on the water creates both tension and resistance, causing the rod to flex and load. Remember, the rod does the work. Your arm and wrist merely set it in motion (D).

sending the fly to its target (F).

Wind is the fly fisherman’s nemesis. I know people who literally reel up their lines and hang up their rods when wind appears. Unfortunately, they are missing some good angling opportunities—fish don’t stop feeding (unless a hatch is blown off) just because the wind blows.

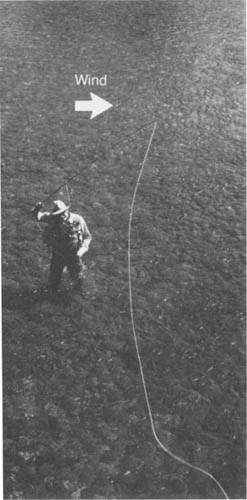

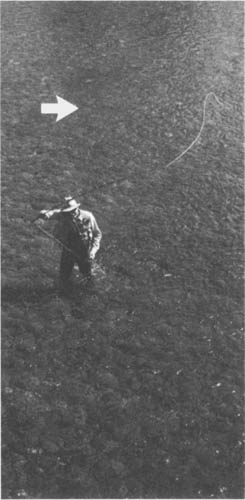

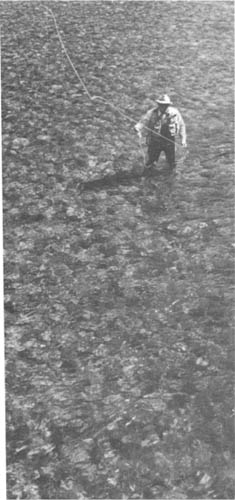

Wind blowing directly in your face, although not pleasant, can be dealt with by increasing line speed through the use of the double-haul cast (more in a moment). Crosswinds create greater problems. If you are a right-handed caster and the wind is blowing left to right, the line and the fly will be blown away from you, diminishing your cast’s accuracy. When the wind is blowing right to left, the situation worsens; to some right-handed casters, the fly can quickly become a lethal weapon. To rectify this problem, simply move the cast from the right side of the body over to the left. Remember, you are still making your normal cast. The motion stays within the confines of the clock, but instead of taking the rod straight up and down, lift the rod at an angle up over your head, until the rod tip is on your left side. Go through the normal motions of a cast; the line and fly will be blown away from you instead of into your body. Do not make the cast with your arm coming across the chest, as the motion is awkward and generates little power. In any wind situation, it pays to keep your casting loops tight.

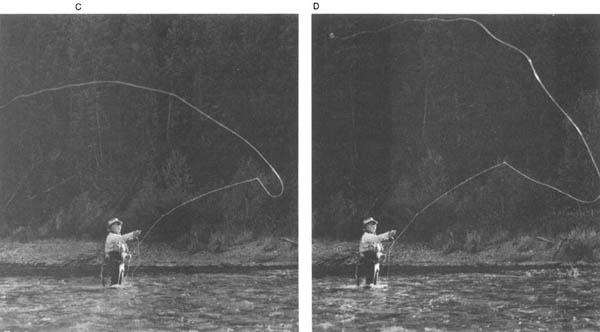

Crosswinds are never fun, especially those that blow the fly and line against you. To avoid this problem, move the cast to the opposite side of your body, where the fly will be blown away from you (A).

Using the basic casting motion, lift the rod at an angle over your head (B), not across your body.

Backcast, following the basic clock position (although now the clockface is parallel to the water) (C).

Let the line extend fully behind you on the backcast (D). Then . . .

Drive, or punch the rod forward to start the forward cast (E).

The line will drive out, just as with a regular cast, with no loss of power or accuracy (F).

Most river systems have multiple currents. Between you and your target area there will inevitably be a fast section of water that, when the line lands, will drag the fly out of position. One way to alleviate this problem is to use what is known as a reach cast, which throws the line upstream or, if necessary, downstream, depending on the current.

To complete the reach cast, make your normal cast, but when starting the forward movement, as the line begins to uncoil in front of you, and before the line lays out completely, quickly throw or reach out to the side with the rod in the direction you wish to go. That will put the line upstream or downstream of the selected holding water. The reach cast is easy to perform and can resolve many of the fly’s float and drift problems.

The reach cast, which can be made to the left or right, has many uses, but is generally used to offset multiple current problems. To reach cast to the right, start your normal forward cast (A).

As the line shoots forward, and while it is still above the water, extend both the rod and your arm to the right (B).

With the rod in this position, let the line fall to the water (C).

To perform a reach cast to the left, once again start with the basic casting motion (A).

As the line begins to lay out, extend your arm and rod either across your body or over your head, again while the line is in the air (B).

Let the line fall to the water (C).

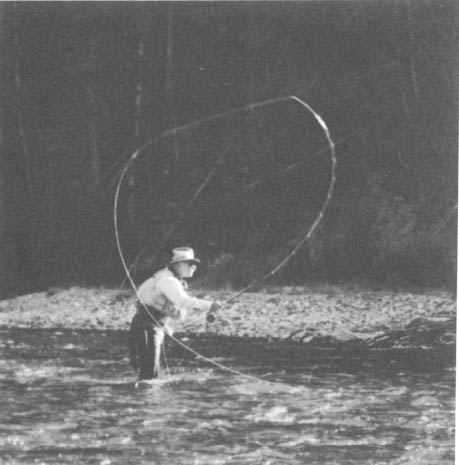

The double haul should not be undertaken until you’ve mastered the basic cast, but once you have reached an intermediate level, you should include the double haul in your repertoire of casts. The double haul is used, 1) for achieving greater distance and, 2) when irritating wind becomes a problem. Essentially, with the double haul you are increasing the line speed to roughly half again what it would be with a normal cast.

Performing the double haul is a bit like rubbing your stomach and patting your head at the same time. It requires two simultaneous movements, both on the backcast and on the forward cast. The cast is initiated with the rod in the normal starting position. With your opposite hand holding the fly line halfway between the reel and the first stripping guide, lift the rod in a normal casting motion, and at the same time, pull down sharply on the fly line with your opposite hand. As the line extends on the backcast, let your rod arm, along with the opposite hand holding the line, drift up and back to the one o’clock position. On the forward cast, as you drive the rod forward, again pull down sharply on the line with the opposite hand. As the rod reaches ten o’clock, release the line and let the remaining line shoot through the guides.

The double haul is used for attaining greater casting distance and cutting through wind. Both are achieved by increasing the speed of the line on the forward cast. As you start your backcast, simultaneously pull down on the line held in the opposite hand (A, B).

In learning the double haul, it is best to take it in steps. First, perfect the backcast portion. After you’ve coordinated the line pull and the cast correctly, try the forward cast. After both have been mastered, put them together. You will probably be amazed at your ability. Remember, don’t overpower the rod. A natural casting stroke, quickness, and power are all that’s needed.

As the line extends behind you, let both the line and your hand drift upward with the momentum of the backcast (C).

As you start to drive, or punch, the forward cast, once again pull down on the line held in the opposite hand (D).

With the line out in front of you, you can either let any remaining line shoot through the guides to finish the cast (E), or repeat the double haul procedure.

The above casts should be learned by every caster. But remember, fly casting is only a means to an end. As you will learn, if the correct fly is not on the leader, and the fly is not correctly presented to the fish, the best casters in the world will never accomplish their goal. It’s not necessary to look stylish or pretty while casting, as long as you become efficient. After you examine all aspects of the sport, I am sure you will agree that casting is what it is—just casting.

An 18-inch rainbow trout uses sound, smell, and sight to move in on its prey.