Fish possess certain important senses that all anglers should understand. In this chapter, we’ll study the habits and characteristics of trout, for it is those fish that fly anglers most frequently pursue. In later chapters, we will concentrate on saltwater and warmwater species.

The trout is certainly the most common target of fly fishermen. It is synonymous with the sport. Therefore, as an angler you should learn to recognize the various trout species and understand their habits relative to their environment.

Years ago, fish biologist and author Paul Needham, in his books Trout Streams and A Guide to Freshwater Biology, placed the cutthroat at the top of the trout hierarchy. He considered the cutthroat the true trout, from which evolved the rainbow and the golden. Today, many fish taxonomists—specialists in fish classification—question this theory, instead believing that some other (distant) ancestor is the forerunner of all trout, including the cutthroat.

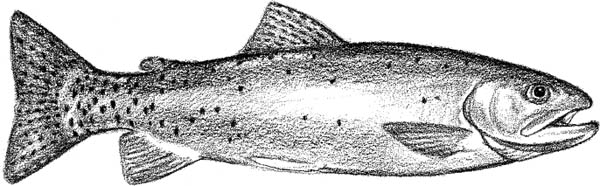

The cutthroat was the original trout in the West. Its range covered the entire Rocky Mountains west to the Pacific Coast. Within that immense geographical area are found numerous subspecies, many of which are located only short distances from one another. Today all cutthroat are classified and referred to under the Latin name Salmo clarki.

From an identification standpoint, the cutthroat gets its name from the two red slashes that appear under and on the outside of its lower jaw. Its brownish yellow sides are highlighted by black spots, and some anglers refer to the fish as “the black spotted trout.” Because the cutthroat is closely related to the rainbow, the two can and will spawn together, both in the wild and through hatchery programs. This unique cross produces what is called a “cut-bow,” a fish with a superb growth rate but little reproductive capacity, especially in hatchery-reared fish.

The cutthroat trout.

From a fisherman’s standpoint, the true cutthroat, although not as active when hooked as a rainbow or a brown, is a great fish. Because pure cutthroat fisheries are likely to be in remote locations, the fish is somewhat easily deceived by the fly. On the Yellowstone River, cutthroat, although selective as the season progresses, for the most part can be disappointingly easy prey.

Since cutthroat migrate to the sea, they provide good sport for Northwest fishermen as they feed along the estuaries before entering the river systems to spawn.

The cutthroat is a very important species, one that needs our protection if it is to survive.

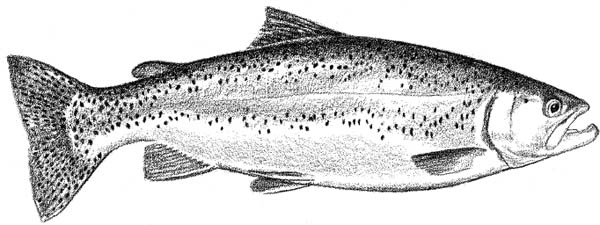

If the trout family has a world traveler it would have to be the rainbow, for it has been introduced in countless trout streams in North and South America, Europe, New Zealand, and Australia. Only the brown trout rivals the rainbow in its range of distribution and transplantation.

Originally, the rainbow was found on Pacific coastal streams of the western United States. But because fish culturists and hatchery managers found the rainbow so easy to propagate, it quickly became the trout for transplant.

The first rainbow eggs were transported to Michigan in the 1870s, and thereafter the eggs were quickly introduced to the Eastern Seaboard streams. Most of that original stock came from the subspecies Salmo shasta, a native of the McCloud and Kern rivers in northern California. Referred to as either the McCloud or Kern River strain of rainbow, today’s fish, because of overzealous fish culturalization, have unfortunately altered their genetic structure, making identification of the original stock difficult.

The rainbow, like the cutthroat, is highly migratory and has many subspecies throughout the United States and Mexico. Taxonomists once felt that the influence of salt water divided the family of rainbow into two distinct species, gairdneri (what was called steelhead) and its freshwater cousin irideus (the non-migratory strain). Today, regardless of these early distinctions, all rainbow trout are scientifically termed Salmo gairdneri.

The rainbow is easily distinguished by a red stripe that travels the length of the fish from gill plates to tail and by hundreds of black spots covering the dorsal (back) side of the body. For anglers, the rainbow has few equals. It can be highly selective and at the same time quite “gregarious” in coming to your offering. When hooked, it puts on a display of long runs and active aerials, for which it has become renowned. There is no doubt that the rainbow trout will always be central to the fly fisherman’s world.

The rainbow trout.

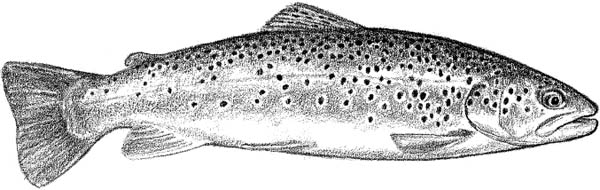

If there is one trout that quickly gains the respect of fly fishermen throughout the world, it has to be the brown trout. Not an American breed, the brown comes from a range that originally covered large parts of Europe and Asia. In all probability this was the “speckled fish” that the Macedonians were catching with their primitive flies in northern Greece 4,000 years ago.

The brown trout arrived on this continent in the early 1880s and immediately received criticism from the brook trout fishermen of the Eastern Seaboard. Because of its intelligence and determination to survive, the unsophisticated approaches that were adequate for catching brook trout failed with the brown. For this reason the brown trout has survived nicely in many eastern and midwestern trout streams over the years. Later, the brown was planted in the northern Rockies, South America, and New Zealand, ranking it a close second to the rainbow in world distribution.

Because it is more difficult to raise in hatcheries, the brown trout’s use in stream planting programs has been limited. Fish culturists, however, have come to realize that because of its ability to withstand warmer temperatures, marine degradations, and fishing pressure, the brown may be the trout of the future.

A migratory fish, the brown, like the rainbow, was divided into sea-run and freshwater varieties. The sea-run fish was called Salmo fario and the stay-at-home fish Salmo trutta, which has now become the generic taxonomic name for the species as a whole. There is also a distinction made between the original strains. Those that came from Germany were referred to as the “German brown”; the others, reared in a Scottish hatchery, were known as the “Lochlaven brown.” Today, the two are difficult, if not impossible, to distinguish and are known collectively as German brown.

The brown trout.

The brown trout is easily recognized by its butter-colored sides, highlighted by black and red spots that follow the lateral line of its body. Early American fishermen thought it to be ugly compared to the beautiful brook trout, but today our fondness for the fish has rendered it a beautiful specimen indeed.

From a fishing standpoint, the brown has no peer. A cut above other trout in intelligence, it demands knowledge, experience, and cunning of the fisherman who tricks it into taking his fly. When hooked, it runs for every obstacle in the stream that might entangle your line. A true warrior, it will make long runs, jump, and totally exhaust itself in the effort to get free. Each time I catch a brown trout, regardless of its size, I have an inner feeling of accomplishment that I don’t necessarily get from catching other trout. I am one of those who truly believe that the brown is a cut above its brothers.

The brook trout was the original trout of the eastern and midwestern United States—the eastern counterpart of the cutthroat. From the north, in Canada, its range extended south to the streams of Georgia and west as far as the headwaters of the Mississippi. It was this beautiful fish at which early North American fishing was aimed.

Strictly speaking, the brook is not a trout, but belongs to the char family, which includes the Lake Trout, Dolly Varden, Arctic Char, and a few other species. Its scientific name is Salvelinus fontinalis, meaning “fish of the springs.” Its char characteristics require that it live in very clear and cold water, and because of that requirement, populations have continually shrunk in the East and Midwest, where the above requirements have disappeared. Today the largest brook trout are found in the cold, remote reaches of its northern range and in the West where there is coldwater seepage.

Because the brook does not live as long as other trout species (usually four to six years compared to a rainbow’s or brown’s six to eight years), it never achieves immense size. The largest on record is only 14½ pounds, caught on the Nipigon River in Ontario, Canada, by Dr. W.J. Cook. Larger brook trout have been reported in South America, but none officially documented. Today, the largest brooks are caught in Labrador and Argentina.

Brook trout planted in western Rocky Mountain streams differ genetically from their eastern forebears due to hatchery techniques. Overpopulation from planting is the general rule, especially in high lakes and beaver ponds, and as a result, brook trout tend to run small.

The brook trout.

The brook trout is probably the most beautiful of our freshwater fish. Its sides and back are various shades of gunmetal grey, highlighted by cream, orange, and red spots. Its fins are nicely edged in white, and during spawning the belly will turn a lovely orange-red color.

Fishermen prize brook trout not just for their good looks but also for their active defense of their freedom—and for their culinary qualities. A bit “gregarious” and many times a little foolish, they accept a fly readily and are easily caught. Fishermen who breakfast on their catch will always rank the brook at the top of the list. Since their populations are not hurt by the elimination of a few fish, the brook trout is ideal for a streamside meal.

A high altitude fish, the golden trout is found in the streams and lakes of the California mountains and the Rockies. As a general rule you must hike to find them. Because of their habitat, goldens are smaller than rainbows and browns.

The golden, Salmo aquabonita, originated in the headwaters of the Kern River in California and was transported to other alpine locations in Idaho, Wyoming, Montana, and some other western states. Today the largest of the species, reaching 10¼ pounds, have been caught in these northern Rockies locations.

This trout is instantly recognized by its solid golden color, highlighted by a few black spots and red striping along its lateral line, belly, and gill plates. It rivals the brookie as one of the prettiest and most unusual-looking of the trout.

The golden trout.

Because goldens live in high lakes they may exhibit a fickleness that is characteristic of alpine dwellers. Determining their specific aquatic diet will help, and when that is discovered and appropriately matched, they accept standard flies easily. When hooked, goldens can be as active as any other fish, depending on the temperature of the lake. To catch one of size is always a treat that more than justifies the long walk and difficult search for the golden’s secret hiding spot.

To fully understand trout behavior, and thus be able to fool them with a fly, you must know something about their sensory apparatus—hearing, smell, and sight. Thanks to their aquatic environment and the challenges to their survival, trout have evolved especially sophisticated sense organs.

Many anglers make the mistake of assuming trout and other fish to be stupid. Our experience with hatchery-raised, pen-fed fish has probably reinforced this attitude. But fish raised in the wild are far from stupid; in fact, they often prove to be brilliant when matched against a fisherman. This brilliance, of course, is not manifested in the form of reasoning, but rather in an acute, instinctive cunning.

Fish do hear, but in different and in some respects more sophisticated ways than humans do. They not only detect frequencies within the range of the human ear, but can also distinguish very low frequencies that are inaudible to us.

Fish have two sound receptors. The first runs along the lateral length of the fish’s body and is designed to pick up general frequency vibrational information. The second receptor is an ear, located in the inner skull, used to detect the movement of tiny aquatic organisms, which make up the fish’s diet. The ear can pick up frequencies very much lower than the human ear can detect and thus are able to locate invertebrates even when the water is murky. The sound of a large fly, such as a grasshopper, landing on the water is well within the range of this ear.

A fish cannot distinguish the human voice outside its water environment because the water acts as a muffler. Talking loudly on a trout stream therefore will not disturb the fish. On the other hand, throwing rocks into the water, banging oars on the sides of boats, or wading clumsily is easily identified as a danger signal by the fish.

The olfactory sensors in fish are much more sophisticated than once was thought. Years ago, it was not quite understood how salmon and other migratory fish found their way back to their original spawning beds. Credit for this amazing feat has now been assigned to the fish’s olfactory system, and this is a clue to just how sensitive fish smelling apparatus in general is, especially when it comes upon alien odors. Because man comes from an environment with an array of smells that have nothing to do with the aquatic world, he can unsuspectingly transmit many alarming odors to the fish. The smell of tobacco and, worse, petroleum-based products such as insect repellant, line cleaners, and fly dressings can warn fish away from your fly.

Friends and I once gathered handfuls of live grasshoppers and offered them to the fish, producing a frenzy of enthusiastic feeding activity. Next, I presented a close artificial imitation dressed with a commercial silicone-based fly floatant. A fish quickly rose to the surface but would not take; it followed about an inch away, finally slipping back to its holding spot. We then applied to the same artificial fly a product designed both to float the fly and to disguise human odors; the same fish was quickly caught and released.

That kind of situation may happen only occasionally, or it may happen more than we realize. Whichever the case, it’s important to know what is on your hands that could be transmitted to the fly. There are some commercial products that will disguise the alien smells that so abundantly surround our human life. Because the olfactory receptors are located on the front of the fish’s head, you can bet that the trout will use this extraordinary power to its advantage when examining your fly, especially if it is out of the ordinary and doesn’t conform to the criteria of the materials the fish is feeding on.

It’s hard to say whether sound, smell, or sight is of greatest importance to fish. But it is sight that most fishermen concentrate on when they try to fool fish with a fly. We know that sight is important to the fish, for before it actually takes the food in its mouth it must see and accept it. Nevertheless, the water environment makes the fish’s eyesight different from our own in important ways.

A trout’s eyesight is quite acute, but its water environment limits the distances it can see clearly. It can distinguish movement from far away, but actual identification of that movement may be impossible. Where the trout excels is in its ability to focus at very close range—within an eighth of an inch. It is this ability that often explains a failed hookup when the fish has seemed to devour your fly. Slow-striking by the fisherman is not the cause; the fish has merely changed its mind and rejected the imitation at close range.

Fish can also make judgments based on color and profile. Behavioral research has shown that fish react to color, not merely primary colors, but subtle shades and hues. Coloration becomes insignificant only at the darkest part of the day, around midnight, when fish seem to see in shades of gray and black. Therefore, a fisherman who disregards color when selecting his fly is in for a big surprise.

All of a trout’s food, on or in the water, is perceived through what is known as the trout’s “window.” Since the trout cannot see long distances, only food appearing within its viewing area gets its attention. The window is cone- or megaphone-shaped, extending from the eye upward at an ever-increasing diameter. The diameter of the circle at the surface will vary with the depth of the fish. The deeper the fish, the wider the cone; the shallower the fish, the narrower the visual cone.

Only when an item passes into that visual cone can a fish truly distinguish and inspect it. If the object is outside the cone, the fish may be alerted that something is floating toward it, but, again, only when the food actually floats downstream and enters the cone does the fish’s sight take over. Thus, to increase our chances of a strike, we must duplicate that natural sequence of activity in presenting our fly to the fish.

The Trout’s “Window”

The deeper the fish is in the water, the larger its cone-shaped “window” of vision. Only when an object passes into this window can the fish inspect it.

Once a fish, or a likely holding spot for fish, has been located, the inexperienced fisherman usually delivers his fly directly at that spot. Because the fly has not drifted naturally into the fish’s field of vision, success is unlikely; the imitation has not arrived in the same manner as real food. The fisherman should therefore place his fly upstream of the fish’s holding area and allow the fly to float downstream into the visual cone, thus duplicating nature.

The other senses, touch and taste, can be important to fish, but it is difficult to understand where one sense takes over from another. We do know that fish are extremely sensitive to the texture of a fly, natural or not. A hard-bodied artificial that looks technically correct often will be rejected, whereas a soft and fuzzy hoax will be more readily accepted. Here, touch has obviously influenced the fish.

Whatever you believe to be the most important of its senses, you must keep in mind that all the fish’s senses are highly developed, subtle, instinctive, and adaptive, and that it constantly uses them to survive. Fishermen are just one, if perhaps the noisiest, smelliest, and most visible, of his enemies.

All right. We have examined the principal species of trout and how they use their senses for survival. Now we must look at where and why they locate themselves in a body of water. To overlook this aspect, despite everything else you know so far, will most certainly reduce your chances of success.

Understanding where fish locate themselves within a stream is fundamental to fly-fishing success.