To the inexperienced angler, reading or understanding fishable water can be both mysterious and confusing, but if you are to become successful with a fly, knowing the fish’s environment is a must. Learning the unique characteristics of trout habitat means studying, observing, and actually fishing a stream. Eventually, you begin to “see” the water in terms of its potential for trout fishing.

In many ways, fly fishing is a sport learned through trial and error, especially with regard to reading water. Water is classified by fishermen into three basic categories: 1) flatwater or spring creeks, 2) lakes and ponds, and 3) freestone, or fast-moving, streams. In this chapter, we’ll focus upon the most readable and most commonly fished water, that of freestone streams.

When one thinks of trout streams, it is the fast-moving, tumbling mountain versions that typically come to mind. Called “freestone” streams because their water moves freely and quickly over a stone or rock base, this fast-moving water yields areas of suitable shelter for fish to rest or remain stationary (hold). Before learning about these places, though, let’s make sure we understand some things about the first ingredient to a stream’s productivity: its water quality.

The mere existence of water does not guarantee that it will be suitable for trout or for any other fish. Water may flow crystal-clear through a pristine setting, but if it lacks the necessary minerals and chemical and organic compounds, neither fish nor other aquatic life can flourish.

The ecology of a trout stream is a complex weave of interrelated elements. Stream biologists consider a host of variables—dissolved oxygen, hydrogen sulfides, and nitrogen levels, for example—when determining the quality of water. All are important, but over the years I have found one factor to be of overriding importance to waterborn organisms, the alkalinity level of the water, or its measured Ph factor.

Spring creeks, such as this one in Pennsylvania, are normally rich in natural chemicals vital to fish and insect life.

A stream’s alkalinity is the measure of its concentration of calcium carbonate, a chemical usually formed from carbon dioxide and various limestone salts. The greater the concentration of calcium carbonate, the higher the alkalinity; the lower the concentration, the more “acid” the water. The more limestone found in the area where a stream drains, the stronger the likelihood that the stream can support aquatic life. Why?

Alkalinity is measured according to a Ph scale of 1 to 14, 7.0 being neutral, neither acid nor alkaline. Trout and other freshwater fish have an internal Ph slightly higher than 7.0. When water is highly acidic (the opposite of alkaline, which is called “soft water”), these fish use most of their bodies’ energy trying to maintain a more neutral Ph balance. As a result, acid-type streams affect both fish growth and total population numbers, mostly for the worst. Aquatic insects follow the same course, which is one reason there is so much concern about acid rain and its effect on our waterways.

Streams with a Ph factor between 7.3 and 7.5, or hard water, are very precious. They are high-yield fish factories, producing dense populations of aquatic insects, which in turn are fed upon by thriving numbers of trout and other species. Classic examples of this type of water include the fabled chalk streams of England, the great Pennsylvania limestone waters, and the spring creeks of the northern Rockies.

As you can see, a stream’s chemical content is vital to fish, but they have other, equally important, needs: namely, where they will live within the water system.

Fish concern themselves with three fundamental needs: 1) security, 2) low current flow, and 3) food supply. These three elements will determine where they will locate themselves within a given waterway.

Security is of greatest importance to a fish. Over the course of the fish’s life it is subjected to numerous dangers, mostly owing to its role as food for higher forms of life. It is only later in life, after it has grown large enough to be a victim in the old hook and line game, that fishermen join the fish’s list of predators. During growth, fish do head-on battle with water scorpions, small mammals, snakes, and other fish. Winged danger from birds, such as blue herons, kingfishers, eagles, and osprey, is also omnipresent. Consequently, a trout’s first concern is to locate a home that offers physical protection from all sides and from above.

Fish in a stream will also secure a place where the current is greatly reduced. Just like humans, a fish is naturally reluctant to fight the current, for, in its case, the energy needed to do so reduces its ability to perform other survival tasks.

Ideally, rather than moving for food, the fish locates itself where food continually goes to it. That means finding a spot where the current moves the food, though once again, the fish seeks a careful balance between the energy it must expend to hold in the current for its meal, and the meal itself. Security and current speed factors, always take precedence over food supply; though a fish can and will move to wherever a meal is being served, it will do so especially if the new spot is more advantageous.

A fish is territorial about its secure spots, or holding lies. It will protect its home, driving other fish away from the prime spot. Several fish can exist within a given hold, but the biggest fish will typically occupy the most advantageous locations.

All fish have a natural tendency to migrate, primarily for spawning and/or for a better food source. Most resist daily or weekly migration because, once again, the energy expended would be too great. Nevertheless, frequent migration does occur. On any day, fish may be driven out by other fish, or they may be caught and taken out by fishermen. Regardless of what causes a fish to abandon its hold, the space will quickly be taken over by another.

Each stream, regardless of geographical location, has its own set of fingerprints, or characteristics, that make it unique. Actual on-stream experience is important for the newcomer, but there are some general stream characteristics that always indicate the possibility of good shelter for fish. Depth and reduced velocity, especially combined, are two of thé most important.

Time and again I have found depth and depth changes to be significant indicators of holding water for fish. If we could view a stream in cross-section, we would see that water current works as logic would predict. Because air offers little resistance, the top layer of water has the fastest current. As we go deeper the current becomes slower. The very bottom is the slowest of all, owing to friction from the bottom itself. If there isn’t sufficient depth (about two feet), fish will most likely not be found there.

Normally, the deeper and slower the water, the greater the number of fish.

However, depth alone does not always denote good holding water. Unless there is something to obstruct the swiftness of the river’s flow, such as uneven rocks and boulders, depth can be useless. One season I fished a run of water that, to the eye, looked ideal for fish. It was a large run with a thigh-deep center. For the entire season, however, I was disappointed in both the number and the size of fish the pool produced. Finally, to relieve my curiosity and frustration, I donned a mask and snorkel to have a look at the pool from a fish’s point of view. What I saw was an incredibly smooth streambed, with rocks of uniform size and type, providing absolutely no protection from the current. No wonder the pool was such a poor producer.

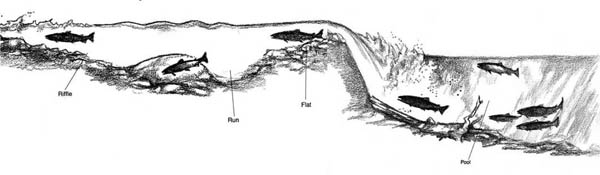

Now that you understand the importance of depth and water velocity to fish, let us define the four basic types of water that represent various degrees of depth: riffles, runs, pools, and flats.

Fish hold in many places in a stream. Some are not easily detected by the inexperienced angler, but the big four—riffles, runs, pools, and flats—should be recognized and learned by every fisherman.

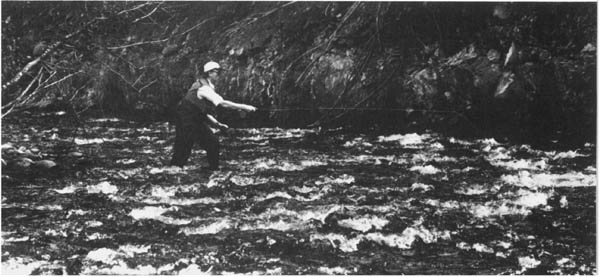

A riffle is the fastest fishable water in a stream. It may be only knee-deep—perhaps two-and-a-half feet of water—but it is sufficient holding water for fish. What creates the riffle effect of the water is large rocks, either exposed or unexposed. The rocks obstruct the current and create the holding areas. Fishermen often refer to this type of water as “pocket water,” and angling in it as “fishing the pockets.” Depending upon the size of the stream, the pockets or “slicks” created by the obstructions can be small or quite large. But as great as this water is, it can create fishing problems for the angler.

Because the water is moving very quickly with erratic current changes, controlling the fly isn’t easy. Short and/or direct upstream casts are often needed to control the speed of the fly as it passes through and over the holding water. Short casts allow you to lift the fly line over multiple crosscurrents, and upstream casts keep the fly in one continuous current. (More on these fishing techniques in Chapter Seven.)

Riffles.

This is generally the fastest fishable portion of a stream. With their small areas of smoother pocket water and slicks (both downstream of rocks), riffles are always worthwhile fishing spots.

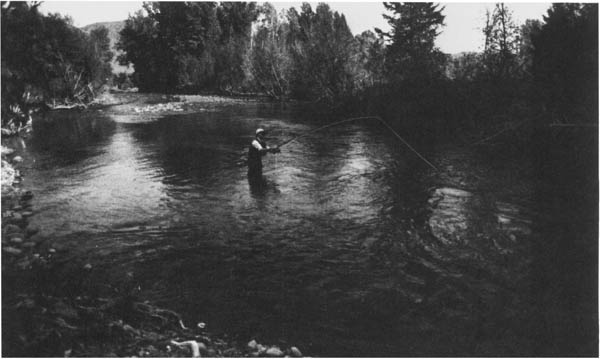

Runs.

Runs are classic fly fishing locations. Coming off a riffle, or fast-water stretch, the stream both slows and deepens, making for an ideal trout habitat.

Because of the water speed created by a substantial gradient drop, a riffle often turns into a run of water, one of the most important water types in the river system. A run will be both deeper and slower moving than a riffle. First, the descending fast water erodes the bottom, adding depth to the area, and, second, because the bottom begins to flatten out, the current tends slow down.

A run is usually about waist-deep (three-and-a-half to four feet). Because the current has slowed measurably compared to the speed of a riffle, a run is a delight, not just for the fish, but also for the fishermen.

Another characteristic of a run is that one part, either the side or the middle, will be deeper and a bit faster than the rest. There will be a definite center current. Fish will hold both in the deepest part and in the shallower water next to this heavier center current.

Runs are the great classic water for all types of fishing. Because they are often numerous on a stream, good quantities of fish will hold throughout. Their current is less erratic than that of a riffle, so fly visibility and drift are not the problem that they are on faster water. Runs should be fished systematically, starting at the tail and moving upstream, fishing all parts.

As mentioned, runs of water are generally considered the premier fly water in a trout stream. With the possible exception of flats, a run is generally the maximum depth from which fish will feed to a surface imitation, regardless of a hatch. But there is deeper water still, and this we call a pool.

A pool is perhaps the most easily distinguished type of water, if for no other reason than that it offers a good swimming hole for non-anglers. It is created either by heavy plunging water, like a waterfall, or by a dramatic gradient drop that erodes the bottom to a depth of six feet or more. This depth eliminates many of the angling techniques employed on other types of water.

Fish are generally reluctant to move more than three-and-a-half to four feet upwards from the bottom to take aquatic surface insects. They will do so only when the hatch is significant enough—when there are insects of sufficient size or quantity—to warrant the energy expenditure necessary to intercept these tasty morsels. Therefore, more often than not, pools are best fished with weighted nymphs and possibly streamer imitations. A pool’s depth may even require sinking-type fly lines—sink-tips or wetheads—for the angler to fully work the fish holding near the bottom.

In general, it is the slowed water and overall depth that make pools ideal holding water for trout. They should never be passed up.

Pools.

Deep pools are the most easily-distinguished holding waters. Because of their depth, they are often fished successfully with underwater fly patterns, such as nymphs and streamers (more later).

Flats.

Flats are characterized by shallow, slow-moving water, which must be approached cautiously lest you spook the fish. Lighter leaders, more precise imitations, and perhaps even a downstream presentation of the fly are often required (more on presentation later).

The last of the big four is the flats. As the name implies, these are large flat sections within an otherwise fast-moving stream. With little gradient drop in a flat, the water moves slowly, with minimal surface disturbance. Flats are generally even in depth from bank to bank, and relatively shallow throughout. A center current is not prominent as it is in a run of water.

Because the current is even and slowed, flats can become good stationing water for trout, especially while an insect hatch is in progress. Fish will move into these areas where they can easily locate and pick off the insects drifting about. But because of the shallower water and relatively undisturbed surface, the flats may not be the fish’s primary shelter area. Caution should be the rule when approaching and fishing these areas.

Fishing flats requires care in casting and presenting the fly. The slower the water, the more easily trout can spot imperfections. Leader size can be significant and, because the surface is undisturbed, the fly itself must conform more closely to the natural.

You will quickly learn that runs, riffles, pools, and flats overlap each other, and it is sometimes difficult to distinguish where one begins and the other ends. Riffles can quite gently transform themselves into nice runs of water. And runs, especially in their tail sections, can develop into flats. But if you can learn to distinguish these four basic types of water you will be well on your way to adequately fishing most of the best areas in freestone streams.

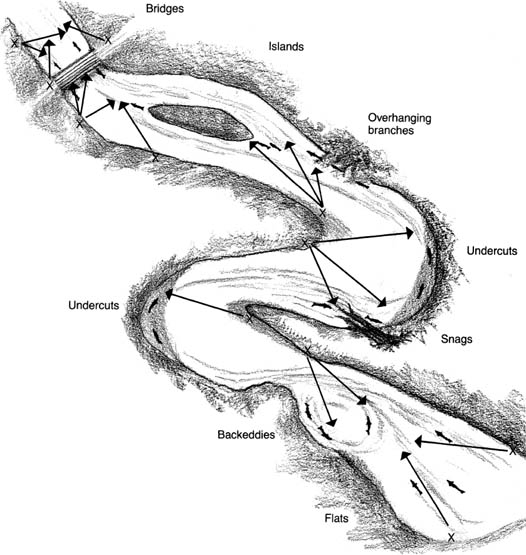

In addition to the big four, there are other sections in a stream that hold fish and require specific techniques and considerations. River bends, undercut banks, fallen trees, islands, stream inlets, drop-offs, and back eddies are just a few.

Every river eventually makes turns, creating bends. These bends may be radical or gentle, but always they offer the strong likelihood of holding trout. Owing to water velocity, the deeper water will be to the outside of the bend, where the action of the current has eroded both bank and bottom. Larger fish gravitate to such spots. During a hatch, the fish may move into shallower water on the inside of a bend to feed, so care must be taken on approaching and fishing turns in the river.

To fish a bend, try taking up a position on the inside of the curve, fishing across to the deeper water. Standing on the outside bank puts the fish at your feet and a presented fly will tend to be swept toward you. It may not always be possible to reach the inside of the curve, especially in bigger rivers, but it should always be your goal.

Undercut banks are generally created by a radical bend in the river. They are excellent homes for fish. Not only is food being swept in to them, but security is assured by impenetrable overhead and side protection. Undercuts are typically found along oxbow-type streams that wind their way in serpentine fashion through meadows. Fish them from the inside portion, allowing the fly to be swept next to or into the undercut.

Banks don’t have to be undercut to provide good trout habitat. Current is often slowed along any bank, and brush and trees afford the fish invaluable overhead protection. Food is also generated at streamside. For these reasons, you can bet that, if there is sufficient depth, the bank will be occupied by a fish. Note, however, that if the water is too shallow, all the other benefits of streamside living will not induce a fish to locate there.

Banks and overhanging trees.

Slow-moving water along a bank and overhead protection provided by trees and brush afford ideal holding water for trout.

Any place trees have fallen into a river system provides good fishing lies. The tree acts as an obstruction, very similar to a rock. The upstream portion of the tree, or snag, will slow the current, and if the tree is big enough it can create quite a substantial space. Below the snag, the water will slow dramatically, which all fish love. Unfortunately, when you hook a fish near a snag there is a good chance the fish will make macrame of your leader by weaving it around projecting branches. To avoid that, you must be craftier and more forceful than usual in working the fish out into open water. I have seen many a good fish escape in the tentacles of downed trees.

Rocks and boulders.

Fish hold not only near the downstream side of rocks and boulders, but often near the upstream side as well.

Islands are another fishable area in trout streams. Most are nothing more than very, very large rocks. The upstream portion of these obstructions creates an immense slackwater. Along the sides of the island the current will be slow, but is the most likely holding spot for trout is downstream of the island at the place where the two channels meet. Reasons: First, the two-current impact creates turbulence, which, in turn, erodes the bottom and adds depth; second, the opposing forces tend to neutralize one another, slowing the current. The downstream slackwater created by an island can in some cases extend a hundred yards downstream before the slowed water gathers steam once again. Never pass up islands, for they almost always hold fish.

The place where smaller streams join larger ones is essential water for fish. An incoming stream can carry a higher water velocity, which will tend to dig out and erode the bottom, adding depths where fish may lie. And, as with islands, the joining currents will offset each other, slowing the water for some distance.

Inlets, or side streams.

Incoming streams usually deepen and neutralize the flow of the main stream at the point where the two intersect. Too, they offer an additional food source and, sometimes, cooler water, both desirable to trout.

There is also the matter of temperature. If the main stream tends to heat up in mid-summer, fish will congregate around inlets where the water is apt to be fresher and colder. The Firehole River in Yellowstone Park is a classic example. By August, the Firehole reaches temperatures that are uncomfortable for trout, and, as a result, the fish will move near inlets or even make their way up the sidestreams, seeking cooler water. Incoming streams can also bring in new types of food that fish may find succulent. Explore these waters thoroughly; they will hold trout.

Fish love to congregate on, or just below, drop-offs. Either subtle or dramatic depth changes, drop-offs almost always are distinguishable by changes in the color of the water. In fishing them, I tell my customers to fish where the light water meets the dark. Drop-offs can be almost anywhere in a stream—along banks as well as at midstream. If the drop-off precedes a deep pool, most of the fish will be found on, or slightly upstream, of the drop-off itself. Present your fly above the drop-off and allow it to float into the pool. Generally, it is where the fly actually passes over the drop-off that the action will commence.

Back eddies are generally situated along a bank and are caused by a heavy center current deflecting from an outcropping—a rock, a tree, or a point of land—and creating a circling effect behind the obstacle. Here the current will actually flow upstream in a whirlpool. Back eddies almost always hold fish. It is important to realize that many of the fish in a back eddy will actually face downstream because the current will be flowing upstream. Present your fly below the fish and let the current carry it to him.

As this drawing shows, fish like to hold in many different locations along a stream or river. Here, the best locations for the angler to fish from are indicated by X’s.

Whether or not you have located a prime piece of water or are an accomplished caster, all can be rendered useless if you do not fish your chosen water carefully and systematically. Regardless of the type of fly you use and the technique you employ, your fishing approach to the selected piece of water is critical.

In most cases, especially in fast water streams, you should approach the fish from behind, actually casting at various angles upstream. Fish face upstream to activate their gills more efficiently for oxygen, and to intercept food being carried toward them. Approaching from behind, you minimize the odds of being detected by the fish. Beyond this basic rule, you must now consider where to place your first, second, and third casts.

Anglers of all abilities tend to make a common but serious mistake. I call it the “grass is greener on the other side” syndrome. Walking into the stream, the angler will deliver his first cast, not in front of him, but completely across to the other bank. What this angler has just accomplished is to disturb every fish between himself and the opposite bank with his fly line. Don’t do it!

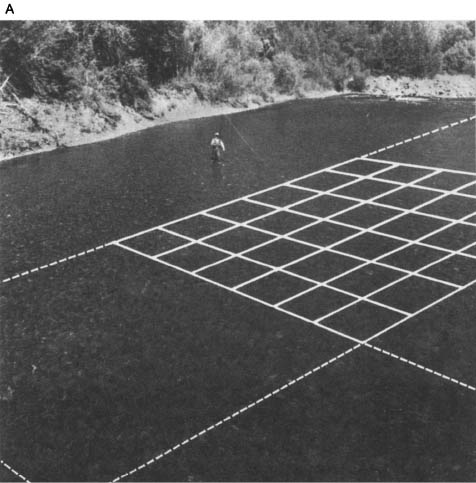

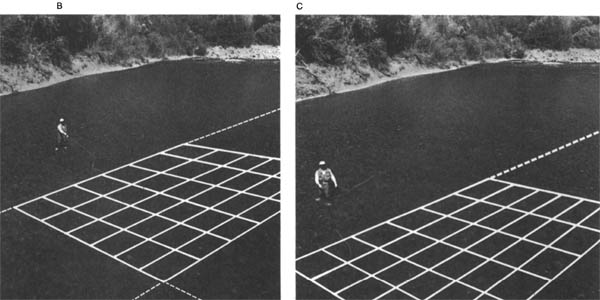

To fish any location properly, approach from the tail or bottom portion and work toward the head. Before making a cast, analyze the holding water, pinpointing where you want to begin and where you will eventually finish up. You are identifying what I call the productive grid of water.

Visually divide your location into sections. If the pool is expansive, you can cut it into three, four, or five sections. Next, mentally impose a grid of two-foot squares onto each section. Your objective is to pass the fly over or through each and every square. Your first cast is short and directly in front of you. After thoroughly working those squares, extend the cast to the next group, and so on, until you have fished the entire section, before moving up to the next.

Fishing the Productive Grid

To improve your fishing success, mentally divide a stretch of productive water into a grid, and work it systematically, starting at the tail and the square of water nearest you (A). After working every square in that area, move upstream to the next section (B) and repeat the process, remembering to make your first cast to the nearest square and working outwards. In this sequence there are three sections. Depending on their size, water stretches can be divided into as many as ten sections, or as few as two.

Another common mistake comes when a feeding fish is spotted in an upper section yet to be worked. Don’t immediately begin casting to him, for again, you will spook all fish between you and the riser. Stick to your game plan, making a mental note of where the fish was feeding to be sure to cover that spot in your sequence. Obviously the fish likes the spot and will be there when you arrive.

After fishing the first section, move upstream (or in some cases downstream) to the next. The first cast is short, the next longer until you have completed all parts of that section.

As you can see, it is important to understand where fish are and how to approach those areas to maximize their potential. Novice anglers often waste time by devoting themselves to spots that will not be productive. Remember, only a certain number of areas within a stream hold fish. Also, you may have chosen one of the finest sections of the stream, but if you approach it haphazardly you will minimize your chances to succeed. From a section that could yield five, six, seven fish, the reckless fisherman is likely to take only one or two. Stop, observe, think, and analyze before entering the water. Your fishing will be much more satisfying if you do.

Now that you have some idea about where fish are and how to approach the water, it is time to learn what they feed on. Without this basic understanding, you will spend fruitless hours, regardless of how well you have mastered the cast or learned to read the water. To ignore what fish eat is perhaps the greatest mistake you can make, and, surprisingly, it’s one even veteran anglers are often guilty of.

The adult mayfly is widely regarded as the Queen of the Trout Waters. Most conventional fly patterns are tied to imitate this insect. Note the upright wings, tapered body, and long, delicate tails: chief means of identifying the mayfly.