In my opinion, the real key to fly fishing success lies in understanding what fish feed on and what fly you can use to imitate those natural food species. Most aspects of fly fishing are fairly static. Equipment evolves slowly, and what was used 20 years ago may still be quite serviceable today. Fly casting is much like riding a bicycle: You might get a little rusty, but the technique never really leaves you. Streams may change because of flash floods or spring runoffs, creating new habitats while destroying others, but fish will still seek shelter in the same types of locations as they did before the stream change.

None of this can be said for the insect world. Although the habits and behavior of those insects that are the primary food sources of trout are somewhat predictable, they are never static. The more one knows about insects and their world, the greater success one will have with fish. Sadly, I estimate that 70 percent of practitioners know little or nothing about this area, and, what is worse, couldn’t care less.

For years, fly fishermen tended to resist the challenge presented by the profusion of insect life that surrounded their prey. Typically, the fisherman would select his fly based upon his own, or a friend’s success, or even on a magazine article that recommended the latest imitations. Little attention was paid to what the fly actually imitated. If the fly worked, great; if it didn’t, the fisherman would haphazardly try another of an estimated 30,000 fly patterns. The question of what was happening on, or in, the water was rarely asked. Today’s angler should start by asking what and why; then, provided he or she has some knowledge of entomology, make a reasonable fly selection relating to the insect activity of the moment.

Many beginning fishermen mistakenly think that, for success, one needs to know all the scientific names and jargon associated with insects, not only locally but throughout the entire fly fishing world. That is nonsense. Knowing what the prevailing insects in their various stages look like is far more important. Eventually, the Latin names of species can be helpful, for they provide a common language with which fishermen can exchange information, but as a beginner or intermediate fly fisherman, you needn’t worry about the scientific names yet. Instead, your main concern should be in identifying insects, and understanding their life cycles and the various stages within those cycles. Nothing more.

In studying trout foods (insects, primarily) anglers concern themselves with those that are aquatic (spend their life in a water environment) and those that are terrestrial (land-based). Each is important.

Aquatic insects represent the largest food group in the diet of freshwater fish. They exist in great numbers, and their abundance ensures their availability to the fish in one stage or another. In its own way, the fish both knows and understands each type and stage of an insect’s life. Therefore it makes good sense for you to know these stages, too.

Generally speaking, all aquatic insects have an underwater stage, referred to as the nymphal or larval stage, and an adult, or actual flying, stage. There are many orders of aquatic insects, each with its own peculiarities. To examine all would be unnecessary and confusing. Instead, let’s look at the main types that make up some 75 percent of the fish’s diet.

The mayfly is perhaps the most important—certainly the most written about—of all aquatic insect orders. Many fishing entomology books have devoted the greater part of their pages to this majestic and beautiful insect. More than any other type, the mayfly is entitled to be called “Queen of the Waters”.

Mayflies are relatively small insects, ranging from three millimeters to about 25 mm, or about one inch, in length. There are literally hundreds of different species throughout the world, but what prevails in one country may not be found in another, and what exists in one region of a country may be absent in another. Since many of the flies are similar in coloration and of course profile, an artificial pattern used in one area could very well work in another, requiring only a change in size for success.

A typical mayfly nymph.

Mayfly nymphs are best identified by their six legs, two or three tails, abdominal gills on the sides and tops of their bodies, and single wing pads.

The mayfly’s lifespan generally covers about one year, and 99 per cent of the time is spent in the water. From an egg, it quickly develops into a nymph stage, consuming smaller life forms and growing slowly until it reaches maturity—roughly a year from the time the eggs were deposited. Because there are millions upon millions of mayfly nymphs, and because of a phenomenon called “continual drift,” or daily downstream movement, these creatures are constantly being presented to hungry fish over the course of a year. Nymphs therefore constitute the greatest single food source of the trout, and thus are important as an imitative stage for the fly fisherman.

Upon reaching maturity, at a particular hour within a day, some of the surviving nymphs of a given species will lift off the bottom and struggle to the surface to hatch. Splitting out of their nymph cases, they emerge as fully formed, winged adult mayflies. This first adult stage is referred to as the dun stage because the upright wings themselves are dun or gray in color.

The dun is important to fly fishermen because it quickly invites surface feeding by the fish. The fragile mayfly remains on the water’s surface until its wings become aerodynamic enough for flight. To the trout waiting below, these vulnerable creatures represent an easy meal. To the angler waiting above, this stage represents perhaps the greatest delight of the sport—dry fly fishing (more later).

The duns not ending up in the stomach of fish will lift gracefully from the water and proceed immediately to the bank, where they undergo a second metamorphosis, unique to the mayfly, during which they shed their minutes- or hours-old identity and pass on to the final mating, or spinner stage.

Anywhere from 30 minutes to 24 hours after reaching this second adult stage, the mayflies gather over the stream or lake in clouds for mating. Each female will descend grasping a male from above, with actual mating taking place in mid-air. After conception, both insects fall to the water, where the female deposits her newly fertilized egg mass. Spinner activity is noticeable when clouds of mayflies form over the water, and a vivid up-and-down flight movement is performed by both insects. After death, which happens very soon after the fly hits the water, the on-the-water profile of the mayfly spinner changes from the upright wing of the dun to a flat, laid out or “spent” winged outline. This spent-spinner stage is, of course, important, from both a fishing and a fly imitation standpoint.

The adult life of these insects is extremely short. The order of mayflies Ephemeroptera derives its name from the insects’ “ephemeral” or “short lived” existence. Propagation is the only purpose of the adult stage, for the adult does not have mouth parts for eating. Fortunately for trout fishermen, these stages last just long enough for us to enjoy some of our grandest moments.

The caddisfly comes from the order Trichoptera. Even though these insects are the subject of few published texts and have never been as popular an imitation as the mayfly, the caddis is extremely important to our sport. Like the mayfly, the caddis has hundreds of different species, and because the eggs are deposited in such great numbers, it represents a primary food source for fish.

The caddis differs from the mayfly in that its entire metamorphosis takes place under the water. From an egg, it transforms into a larva, or wormlike stage, which takes one of three forms: It builds what is known as a caddis-case around its body, it swims freeform, attaching itself to weeds by a fine silk strand, or it constructs a tiny net structure between rocks to catch its food.

The next most important food for trout is the caddis, often called a grandom or a sedge. Characterized by its tent-like wings, the caddis is the primary trout food in many streams.

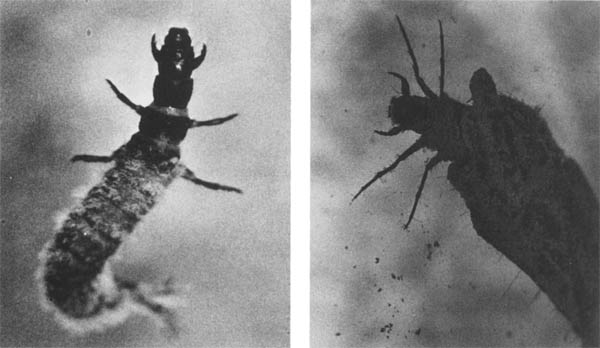

Caddis larva.

Two different typical caddis larvae: freeswimming (left) and case (right). Caddis larvae are chiefly identified by their wormlike appearance, the presence of their six legs behind the head, and their lack of visible wing pads, antennae, and tails.

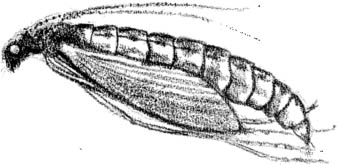

Caddis pupa.

This is the form the caddis assumes as it begins its rise to the water’s surface. Its chief identifying points are its six long legs, two long antennae, and two wing pads on the sides of the main body.

Caddis adult.

The best way to identify a caddis adult is by the tentlike profile of its wings. An adult caddis’s flight somewhat resembles a moth’s.

Case-makers construct their houses out of microscopic debris, particles of sand or organic material available in the waterways they inhabit. The larva stays within this case throughout its larval stage, the case expanding as larval growth occurs. Because these cased caddis—often called periwinkles or rock rollers—do not particularly lend themselves to movement within the stream (they often attach to rocks or other debris), they have not proved to be a very successful model for fishermen to imitate. Duplicating them visually presents no problem, but mimicking their movement (or non-movement) in the water is difficult. The free-swimming caddis-larva is a better bet for fishermen. This unattached, worm-like larva drifts slowly near the bottom of the stream. A good imitation successfully mimics this delectable morsel.

As a caddis larva begins to mature, it either closes off its little case, or, if a free swimmer, makes a small cocoon around itself, to complete its metamorphosis to the adult stage. At full maturity—called the pupa stage—the caddis traps air bubbles in its case and rapidly makes its way to the surface. This rapid upward movement induces slashing and charging rises from the trout that sometimes signal the angler that caddis pupa are on the move. From a back eddy, I once observed caddis pupa hatching and noted that the speed of the rise from bottom to top was comparable to the speed of a released cork rising from the bottom of a bathtub. This rising stage is the most important of the underwater stages of caddis for the fly fisherman.

Upon reaching the surface, the pupa sheath splits open and the adult stage immediately lifts off the water. In profile, the adult’s wings lie tentlike over its body—a much different profile than that of a mayfly. In flight, the caddis somewhat resembles a moth. Flying to the bank, it remains there perhaps two or three days before mating in the vegetation. After mating, it returns to the water to deposit the eggs, again becoming a likely meal for fish.

In general, I have always found the greatest activity in the caddis in late afternoon or early evening. I have seen them by the millions doing their life-and-death dances over streams teeming with hungry trout. Because caddis are very prevalent and important insects, fishermen should carry at least a few of the imitative patterns that suggest the natural. To forget the caddis is to leave a large gap in a well-rounded fly box.

The stonefly is the third most important of the aquatic insects. It’s important to remember, however, that there is no real hierarchy among insects. Each type—mayfly, caddis, stonefly, or others—has its moment when the trout concentrate on it as a food source. It’s just that, because of their numbers, some insects have more moments than others.

Stoneflies are unique in that they must locate themselves in fast-water streams. Although a relatively small order of insects, the stonefly becomes extremely important to the angler at certain times of the year, and its overall size range—seven mm to over 50 mm in length—ensures the attention of even the largest fish in the streams.

The stonefly has two stages, nymph and adult. As a nymph, it may remain underwater from one to three years, depending on the species. The larger species generally have longer lifespans. At various times of the year the nymphs are very abundant, and, because they crawl and cling rather than swim about, they become fairly helpless if detached from the streambed. Thus, fish will readily grab a good fly imitation that is allowed to dead-drift (more on this technique later) through good holding water.

Typical stonefly nymph.

Nymphs are easily identified by their two wing pads, or cases, two antennae and tails, and fuzzy gill hairs, or filaments, surrounding their six legs.

Typical stonefly adult.

Adults can be identified by their double wings folded over the top of the body, their large antennae, and twin, widely separated tails.

On its day of maturity, instead of floating to the surface like the mayfly and caddis, the stone fly crawls out of the water onto rocks, trees, or the bank and splits out of its case, leaving behind an exterior skeleton often observed by fishermen. The adult may live on the bank for three to five days before mating farther up on the land, after which it flies back to the water, where it deposits some 10,000 eggs, and thus, again, becomes important to both fish and fisherman.

Its importance increases with its size. The East has its giant Perla stones, while the West boasts hatches of both the Golden and the famous Salmon flies. What makes these unique among all aquatic hatches is that the flies reach 50 mm in length—about the length of an adult man’s little finger. Insects so large often attract eight-to-ten pound trout that otherwise remain on the bottom, feeding on either nymph or fish forms.

The stonefly also comes in smaller sizes, in both the East and the West. Early brown and black stoneflies occur throughout the country. In the West the brightly colored yellow stones, often referred to as “yellow Sallys” or “Mormon girls,” are abundant enough to provide good fishing activity for all fishermen.

Wherever stoneflies exist they should be fished diligently. Their overall size, both in adult and nymph stages, makes them ideal food for fish. You should be armed with some stonefly patterns, especially if freestone water is your fare.

Depending upon location, midges can be a major food source for fish. They can exist by the billions and can take precedence over all other aquatic insects. The midge falls into the immense order of Diptera, or True Flies, an order containing gnats, mosquitoes, craneflies, and many others.

Midges are found primarily in the slow-moving waters of lakes, ponds, or spring creeks, but can also be found within the slower sections of freestone water. In general, midges are very small in size and for that reason are often overlooked by the unobservant angler. Like the caddisfly, the midge has a larva stage which looks like a thread-shaped worm on the bottom of a stream. At maturity the larva pupates, drifts, and hangs just below the surface of the water before emerging as an adult.

Midge larva.

These simple creatures are best identified by their wormlike bodies and lack of a visible head, body, or tail.

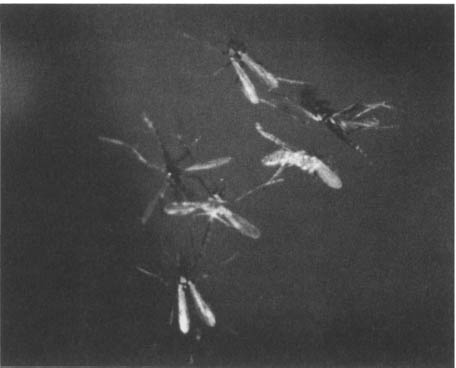

Midge adults.

The adult midge is best identified by its mosquito-like profile and single pair of rounded wings, which are shorter than the body.

All midge stages can be important to the angler, but most fishermen concentrate on the pupa and adult stages. Pupa imitations are tied with very thin bodies and a bulbed head and are fished on long leaders just underneath the surface. The adult will also remain on the surface for some length of time, making it an important dry fly model. Because of their quantity, adult midges often congregate tightly together, creating small balls on the surface. Trout will often choose to concentrate their feeding on these masses, rather than taking one fly at a time.

Anglers are often surprised and fooled to see fish actively pursuing such small insects, passing up larger and more delectable aquatics, such as mayflies and caddis. Recognizing midge activity is important, therefore, especially in slow-water situations when either nothing of consequence appears on the water or, again, very visible aquatic insects are not being fed upon while fish are continually rising. If you look carefully at water surface, you will probably find midges. Your imitation should be fished precisely in terms of size and profile.

There are many, many other aquatic insects of importance, the most significant of which are found in lakes and ponds. These will include damsel-flies, dragonflies, alder flies, and the non-insect form of leeches and freshwater shrimp. Because they mainly inhabit still water we will discuss them in more detail in the chapter on lakes and ponds.

Aquatic insects are the trout’s primary food, but there are times during the latter summer months when terrestrial insects become important, too. Terrestrials don’t live or breed in water, but are land-based and become available to fish when they fall or are blown into the water. In the eastern United States, where most aquatic hatches end by midsummer, terrestrials may become the main food source for fish. In the West, hatches last throughout the summer, but, because terrestrials are in great abundance, they are expected and sought out by fish.

Included in the category of terrestrials are a variety of ants and beetles, the green oakworm of the East, and—the most universal of all terrestrials—grasshoppers and leafhoppers. After landing on a water surface, terrestrial insects are unable either to fly or to lift themselves away, and thus become vulnerable prey for trout.

Fishing grasshoppers can be an exciting and rewarding experience. The fly is large enough to attract big fish, and because the imitation is easily seen on the water and can be crudely presented, it is easily fished by anglers of all abilities. In fact, many times a sloppily presented fly will get the best results.

The knowledgeable angler should carry a full array of terrestrial imitations in various sizes. A fly box should contain both black and cinnamon ants, in flying and non-flying stages, leafhoppers and grasshoppers, black beetles and, if you fish in the northeastern United States, green oakworms. I always carry a few terrestrials with me and have found they can make the difference between success and failure in some highly selective trout waters.

Once a fish reaches a length of perhaps 15 inches, it begins to supplement its diet with other fish. When a fish reaches a very large size, its-cuisine may consist solely of other fish. Referred to as forage or bait fish, the edible types are endless: dace, shiners, the alevian of the Great Lakes, chubs, small perch, the very important bullheads, or sculpins, and, of course, other trout. Flies used to imitate fish are referred to as streamers, for they are tied in such a manner that when wet they flow backward, forming the outline of a baitfish.

To give you an idea of the gluttonous attitude of some fish toward baitfish: I once had a customer catch an 18-inch trout and elect to kill it for breakfast. Upon netting the fish, we found the tail of a five-inch-long sculpin protruding from its mouth—a robust meal in itself for a fish that size. Upon cleaning the fish, we found 18 undigested large stoneflies. And yet, with all this food, some still not even swallowed, it had taken a large stonefly imitation! Where the fish planned to put this latest morsel I haven’t the foggiest idea.

Ants.

Ants are an important food source, sometimes preferred by trout over all others. Many times, an ant imitation will catch fish when all other fly patterns have failed

Beetles.

Various species of beetles, when found in abundance, are another important trout food. Always carry a few imitations in different sizes when you go on stream.

Grasshoppers.

The grasshopper is the king of the terrestrials. Grasshopper imitations in various sizes often take large fish.

Baitfish.

Larger trout supplement their diet with baitfish, such as the sculpin, shown here.

If you are looking strictly for larger fish, fishing a bait imitation, or streamer, should definitely be considered. Large fish spend their time concentrating on other fish as food, and you should give them what they want.

Throughout this book, I have continually referred to “the hatch,” but, to many beginning fly fishermen, the term can be somewhat confusing and ambiguous. In specific terms, a hatch is the actual hatching of an adult insect. But, generally speaking, the term refers to any activity or movement of insect stages above or below the surface of the water. Hatching activities are as inevitable as the seasons and therefore somewhat predictable; we use this predictability as a means of deciding when and where we want to fish.

All aquatic insect species have their ecological niche. As part of the orderliness of nature, each species appears not only during a certain part of the year but at certain times of the day. A “hatch” may last for two or three hours or, if the weather is inclement, for an entire day. Also, hatches of one particular species may appear every day for two to six weeks before completing their yearly cycle. In addition, different hatches of different species can be sequential, overlapping, or simultaneous with others.

A fishable hatch requires insect quantity. Although there is no absolute minimum, generally hundreds of insects must appear on the water before fish will feed. While entomologists may get excited about one insect of a rare species, fish are only interested in those that appear in plenty. A curiosity, therefore, is not a fishable fly.

The mechanism that triggers an insect hatch is somewhat mysterious and not fully understood. Obviously, insect maturation is involved, but water temperature and air humidity can also be factors. An insect has a refined apparatus for detecting the slightest change in air or water temperature and barometric pressure. This unique registering system can either cause a hatch to stall until more favorable conditions develop, or speed its timetable.

During early spring and summer when air and water are often cool, most hatches will commence in early afternoon or at the warmest part of the day. As summer progresses toward its highest temperatures, midday air temperatures can be too hot, with hatches shifting to morning or early evening. Surprisingly, though, it appears to be the humidity of these periods rather than the water temperature that stimulates these shifts. Many entomologists now theorize that nymphs as well as adults have trouble emerging from their cases or their exoskeletal skins without a certain moisture content in the air. Therefore, during the heat of late summer little hatch activity will be found between noon and, say, five o’clock when the air is insufficiently humid.

Weather can also trick insects into hatching. If a heavy afternoon thunderstorm appears, severely darkening the sky, the insects may register that evening has arrived and begin their emergence. While there is heavy overcast or drizzling rain, hatching can occur throughout the day, especially if the hatching species is known to emerge in late afternoon.

We are fortunate to know something about what causes insect activity. Our guidelines are at best general rules, but they do allow us to chart the fishing season with reasonable assurance that a particular hatch or hatches will occur within a general period of time. Without this predictability, fishing a hatch would be a crap shoot at best.

Multiple and complexed hatches present the greatest problems to fishermen. The task is always easiest if just one natural species is on the water and the choice of imitation is obvious. But when several species of one particular type of fly (multiple), or two or more different orders (complexed), are hatching at once, determining the fish’s choice can be difficult.

When two different mayflies of distinctly different sizes appear on the water, the inexperienced angler naturally chooses the larger fly, figuring it is easier to see and fish obviously prefer the greater food content. I have fished hatches where the very large mayflies, the western Green Drakes, were present, but the much smaller Pale Morning Dun (Ephemerella) was there in greater profusion and the larger specimen was completely ignored. As a rule, select the fly that is present in the greatest quantity; quantity takes precedence over size.

In a complexed hatch you may have a mayfly species emerging, a mayfly spinnerfall dropping to the water, caddis depositing their eggs, and a host of midges delicately riding the current. Many times, trial and error must be the rule, but if you can detect the quantity factor, or visually observe what the fish are taking, you can eliminate some of the possibilities.

Stillborn activity has recently been recognized as an important factor in aquatic hatching activity overall. The term applies to a hatching insect that, in trying to free itself of its nymphal shuck, or case, gets trapped. Fish quickly realize that these forms will not fly away and they key on these cripples rather than on the fully developed adult flies. All aquatic orders have stillborn activity, and various flies are tied to imitate this condition. Therefore, especially on selective waters, stillborn is not a category to be ignored by the serious angler.

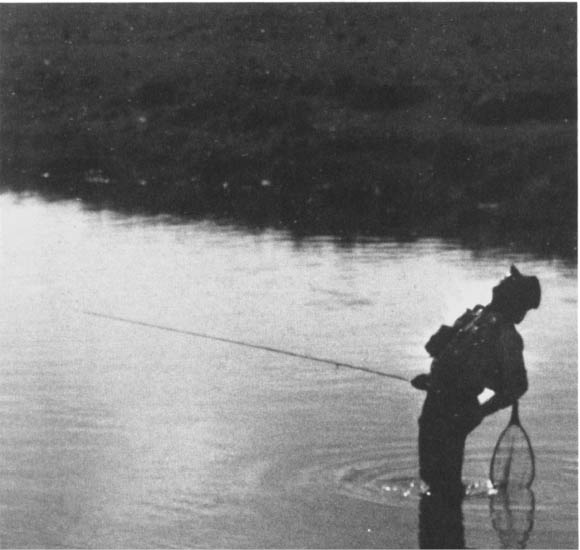

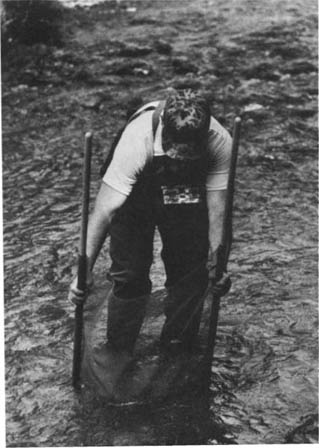

Now that you have learned at least the basic foods of fish, the obvious question arises as to how one finds out what fish are in fact feeding upon. The first and certainly most obvious and simplest method, is observing what insect is on or flying about the water itself. If an unknown or an undistinguishable insect has flown to the bank, it is often wise to walk over and examine the adult for size, coloration, and type. When insects are found or seen on the water, you can easily collect samples by using a small aquarium net carried in the vest. For both immediate and long-term research, actual seining of the river system helps to identify not only insects that are presently hatching but also those species of insects that live within the river system in quantity and are very close to maturity and thus hatching. Seining the river is somewhat laborious but can be accomplished by attaching fine mesh, such as window screening, to two poles or stakes, pushing the stakes into the streambed, and then kicking up the bottom just upstream of the net itself.

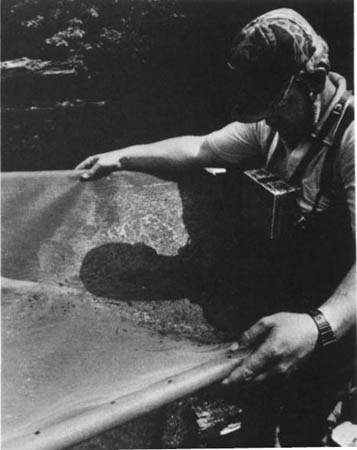

One of the most frustrating situations in the world of fly fishing is when you have feeding fish in front of you and can’t identify or see what the fish are eating, especially in freestone water. One very quick and easy method of solving the mystery is to check small backwaters, eddys, and small side pools of water where insects tend to collect. Many times these areas identify not only what is presently taking place but also what might have taken place earlier in the day or on previous days. And, finally, perhaps the most effective method in identifying insects, or more precisely what the fish has been feeding upon, is to check the actual content of the fish’s stomach and esophagus. This is done not by killing the fish, but rather by pumping its stomach, using a simple, syringe-type stomach pump. This delightful gadget is easy to operate and does not harm the fish. Rather, it efficiently relieves the fish of its morning or afternoon meal. Many times you will be surprised and enlightened at what you find using this device.

Look in the air.

Being able to recognize various insects in flight is a crucial skill for the serious fly fisherman. Often, the answer to what the fish are feeding upon is in the air around you.

Look in trees and bushes.

Examples of both aquatic and terrestrial insects that fish might be feeding upon can often be found in the streamside greenery.

Look in shallows.

Both during and after a hatch, small side pools and back eddies are a good source of information about insect activity.

Use a seine.

A simple seine, made with short poles and fine netting, is an excellent tool for helping to determine which nymphs and hatching insects are present underwater.

Look under rocks.

Even without a seine, you can discover the nymph species present in a stream by examining a few rocks from the stream bed.

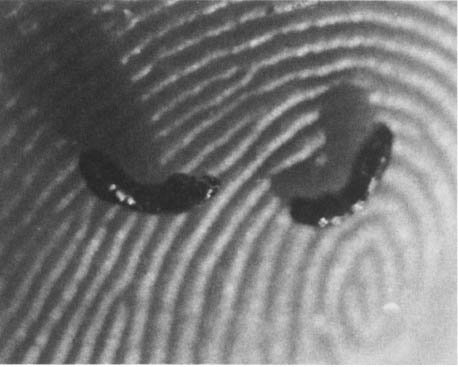

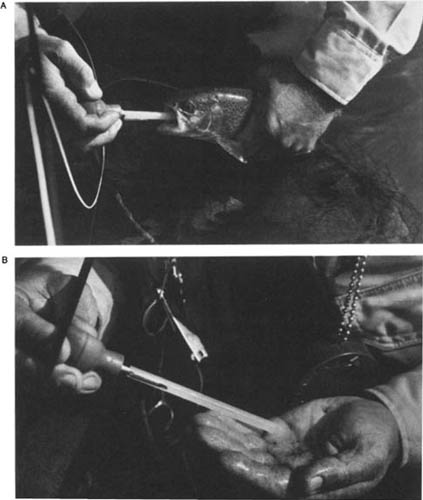

Use a stomach pump.

A stomach pump allows you to examine a fish’s diet without killing the fish. When using one, first squirt a tiny amount of water into the fish’s stomach, then suck out the stomach’s contents (A). Reload the pump with water, squirt the contents into your hand and observe (B). Always clean the pump afterwards.

All else being equal, having made an adequate cast and presented the fly properly, you want a consistent fly pattern, that is, one that works 90 per cent of the time. Unfortunately, many anglers are ignorant of entomology and have not observed what fish are feeding on, and thus concentrate on a fly that, all too often, hasn’t been especially successful.

Most fly fishermen fall into two categories: those who are solely pattern-conscious and those who first analyze what is on the water before going to their fly boxes. The pattern-conscious fishermen concentrate their selections on a small group of flies they have carried over the years, regardless of what these old standbys imitate. As mentioned earlier, their information is obtained from past successes, friends, or magazine articles claiming that the fly will work under any conditions. Alas, life is never so easy. I once went fishing with a gentleman on his home waters, and when I politely asked him what pattern he was going to use he told me, “Mr. Mason, I put an Adams on 30 years ago and I haven’t taken it off since.” Now, the Adams happens to be a very good general-use fly, but with that attitude the angler limits himself to just one of the countless species that do exist and are fed on by fish. I remember another elderly gentleman who told me, “If they don’t want a Royal Wulff, they can damn well go hungry.” Again, in both cases, such an attitude dramatically limits the opportunities to take fish, especially in a selective hatch situation.

In matching a hatch, there are criteria we should follow, especially if we are fishing a dry fly. They include size, profile, and color.

Size is the most important fly characteristic that anglers can duplicate. Forced to choose, I would rather have the appropriate size of fly than its exact profile or matching color. Fish understand size, and the smaller the natural fly, the more exacting the fish’s judgment. Granted, small flies can be troublesome to see, and we tend to cheat a bit with larger imitations than the natural. But, for the most part, we end up cheating ourselves, because the trout know the difference. What often appears extremely small, and therefore close enough, to us will be passed up by fish who are looking for a more specific size.

Very large flies can also be a problem. What logically appears irresistible to us may be just plain suspicious to fish. A hatch of very large mayflies, caddis, or stoneflies does not necessarily mean that the fish will automatically begin to feed on it. These flies represent something so uniquely big that apprehension is the trout’s first reaction. It is only after a few days of random feeding that the fish, having sampled the hatch thoroughly, will become reckless in their approach to an imitation.

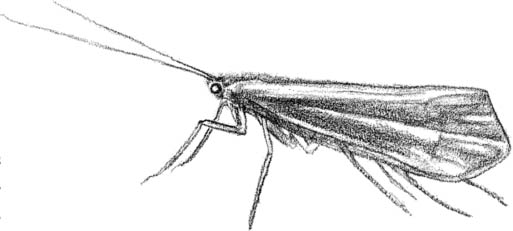

Matching the hatch: size, profile, and color.

Once you’ve determined what’s hatching, find an imitation whose size, profile, and color match it.

Fish also have short memories. If an insect is not seen or has disappeared from the area, fish will soon forget it. Fish need constant reinforcement. I once guided a gentleman who had had great success with grasshoppers in August. He returned the following June for more of the same, but, because hoppers were not out, he caught nothing. He quickly changed his thinking about his choice of fly. Size is important; your fly must conform as closely as possible to the size of whatever is being eaten that day, or that moment, or you, too, will catch very little.

Different insects have their own distinct profiles as they appear on or in the water, and these silhouettes are of great significance to fish. Mayfly duns appear with an upright wing, but the spinners of the mayfly are often laid out flat, in what is known as a spent position. The caddis folds its wings into a tent over its body, and the stonefly has its own way of flattening its wings when not yet spent. Trout understand these profile changes, so naturally we tie flies in shapes that match them. To ignore profile is to ignore an element fundamental to fly imitation.

Years ago, color was given more credence than it presently is. A close color match is usually good enough, so long as size and profile are met. Coloration is pretty much in the eye of the beholder, or flytier. Ten people might sit down to a flytying vise to produce a replica of a natural specimen found on the water, and six different color combinations probably would result. One person might see more yellow where another sees a bit more olive; a touch of gray might be the predominant hue seen by a third person. In all likelihood, all three will work if size and profile are correct. The key here is to select a fly color that is as close to the natural as possible.

There is a staggering number of fly patterns available today, many of which are very close in coloration. Therefore, the beginning angler should choose a simple selection that first meets the basic color of most insects—gray, cream, olive, brown. After selecting a fly pattern, he should then purchase them in a variety of sizes that can meet onstream requirements. Although I dislike the pattern-conscious approach, the following is a basic selection of flies that an angler will need for success.

Adams #12, #14, #16, #18, #20 |

Tan Elkhair Caddis #12, #14, #16 |

Light Cahill #14, #16, #18, #20 |

Olive Elkhair Caddis #12, #14, #16 |

Light Hendrickson #14, #16, #18, #20 |

Little Yellow Stone #12, #14 |

Gordon Quill #12, #14, #16, #18, #20 |

Little Black Stone #12, #14 |

Red Quill #14, #16, #18, #20 |

Hemingway Caddis #14, #16, #18 |

Hairwing Flies (for very fast water)

Royal Wulff #12, #14, #16, #18

Gray Wulff #12, #14, #16

Grizzly Wulff #12, #14, #16

Yellow Humpy #12, #14, #16, #18

Gold-Ribbed Hare Ear #10, #12, #14, #16 |

Green Caddis Larva #12, #14, #16 |

Prince Nymph #10, #12, #14 |

Zug Bug #12, #14, #16 |

Otter Shrimp #10, #12, #14, #16 |

Olive Woolly #8, #10, #12, #14 |

Tan Caddis Pupa #12, #14, #16 |

Brown Woolly #8, #10, #12, #14 |

Olive Caddis Pupa #12, #14, #16 |

Black Woolly #8, #10, #12, #14 |

Black Ant #14, #16, #18 |

Crowe Beatle #14, #16, #18 |

Black Flying Ant #14, #16, #18 |

Dave’s Hopper #8, #10, #12, #14 |

Cinnamon Ant #14, #16, #18 |

Green Oakworm #14, #16 (Eastern U.S.) |

Muddler Minnow #4, #6, #8, #10, #12 |

Black Marabou #4, #6, #8 |

Light Spruce #4, #6, #8 |

Black Woolly Bugger #2, #4, #6, #8 |

Dark Spruce #4, #6, #8 |

Olive Woolly Bugger #2, #4, #6, #8 |

Note that the above list is only a general guide. When in an unfamiliar area, you should always check with the local fly shops for advice. The people there know what is hatching and effective, as well as where and when. Local consultation can be your greatest ally.

Selecting the right fly is important, but even the best fly, if not fished properly, will fail to bring success.