If the fly is not presented properly to the fish, all the money in the world invested in costly equipment and flies, and all the hours spent perfecting your casting technique, will not improve your chances of catching fish. Time and time again, fishermen with the correct pattern for a given situation have little success, most often because their technique did not meet the standards that the fly called for. The fish, you must understand, is unimpressed as to whether the fly is gold-plated or tied by the most skilled craftsman in the world. If the fly does not act as its natural counterpart does while on or in the water, it will be rejected. In this chapter, our aim is learning correct presentation of a fly.

Remember how a trout views its food in its water environment, through its “window” or field of vision? As you will recall, trout do not see great distances. They only visualize and focus on food when it enters or drifts into their cone-shaped window, extending from the eye to the surface. Therefore, regardless of whether you fish a surface or subsurface fly, you must duplicate the situation by presenting your morsel upstream of the fish or its lie, allowing it to float down into view. That is the natural sequence of events to the fish. Presenting the fly directly at a rising trout, or to his holding spot, will all too often produce no results because, once again, the fly did not arrive as a natural insect would. Proper line drift is important, but so is how the fly appears to the fish when entering its field of vision.

All streams have multiple currents. Between yourself and the target area, faster or slower water current will be found; seldom will you find a stream with current equal from bank to bank. These multiple currents play havoc with the fly. The uneven water speeds either push or pull on your fly line, creating a “belly” in it, which, if allowed to remain on or in the water, will ultimately drag or skate the fly across or through the water. Since such movement, for the most part does not conform to natural insect behavior, you must manipulate the line to prevent or eliminate this belly and drag. In other words, you must learn to “mend” your line so that the fly travels at exactly the same speed as the current into which it has been cast—no faster, no slower.

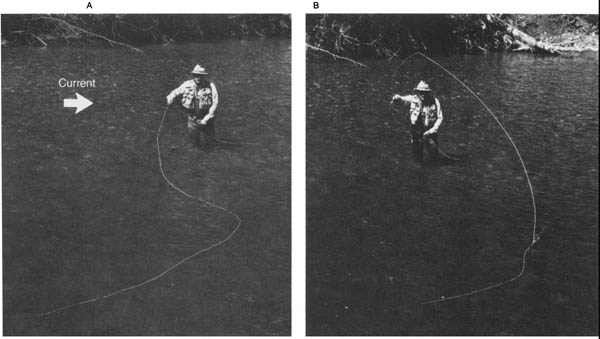

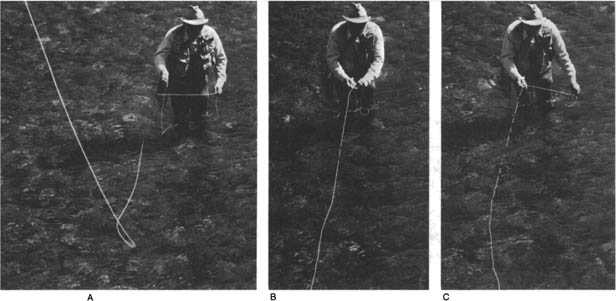

If, as is most often the case, fast water lies between you and your target area after you’ve made your cast, the line belly will quickly form downstream of where the fly lands. With your rod in hand, flip and roll the rod and line back upstream, to eliminate the belly.

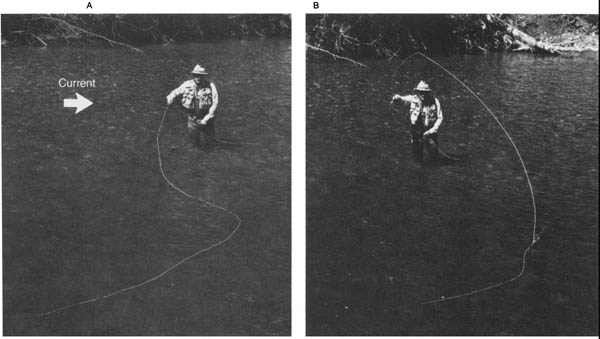

Many times your target is in fast water, while the water between you and it is slow. The fly lands and quickly begins to float downstream. However, the slower current soon slows the line, which forms a belly and restrains the fly’s movement downstream. To counter this form of drag, you must now roll and flip the rod in a downstream direction so that the fly is free to travel at the quicker current’s speed. In general, mending is a matter of watching the belly of the line. Roll the line in the direction opposite to the way the belly is forming.

Use the upstream mend when fast water lies between you and your target area. As soon as the line starts to belly downstream of the fly (A), roll the rod upstream (B). This, in turn, will roll the line upstream (C), eliminating the belly (D). Note: You may have to mend more than once to maintain a drag-free float.

A final note on fly line drag problems: As you progress with your fishing, you will learn to anticipate drag problems before they happen. Upon entering a good run of water, first look at the current and decide what drag problem you are likely to encounter. With practice you will find yourself mending your line before bellies and drag become a problem, which, in turn, will mean catching more fish. Such advance planning will give you a better chance to fool the fish the first time, when he is most vulnerable, rather than the third time, when he may be slightly suspicious.

There are four types of flies we can use to take fish in a stream: 1) the dry fly, or surface type fly; 2) the wet fly, which is fished subsurface; 3) a nymphal imitation, (also fished subsurface); and 4) the streamer, (subsurface, too). Each has its place and requires a different fishing technique that should be part of a successful angler’s repertoire.

A fly line that lands in water moving slower than where the fly lands can cause the fly to stall in the current rather than drift naturally with it (A). To eliminate the upstream line belly caused by the slower current, roll your arm and wrist downstream (B). This, in turn, will roll the line upstream (C), eliminating the belly (D). Be prepared to mend again for longer drag-free drift.

To many non-anglers, fishing the dry fly is what the sport of fly fishing is all about. Unfortunately, some fly fishermen regard dry fly fishing as the only way to fish, and approach it as a near-religious experience. I happen to think they’re wrong—fishing other fly types can be just as satisfying, and in the case of nymph fishing, as we’ll see, even more delicate an art than dry fly fishing. But I understand these purists’ enthusiasm: The ability of the fisherman to see the action take place—to actually see the trout take the fly right before the fisherman’s eyes—does make the dry fly an addictive technique.

The dry fly is an imitation of either an aquatic or a terrestrial insect in the adult stage that rides the surface of the water, making itself accessible to the trout. The fly is tied in a manner to mimic its counterpart in size, profile, and color. Since the way the fly rides the currents must duplicate a real insect’s movements, a few techniques must be learned to mirror nature. They are all needed for successful dry fly fishing.

Fishing a dry fly requires no special equipment. The same rod and reel you use for your other techniques will work fine. Rods were once classified as either stiff, (dry fly action), or soft, (wet fly action). The stiff, dry fly rods provided a quick action for striking a rising fish and a better responsiveness during the numerous false casts often required to dry the fly. Today, a medium-action rod will suffice for both surface and subsurface fishing.

Dry flies are generally tied from naturally buoyant materials. In addition, to facilitate floatation, they are constructed on very light wire hooks treated with a silicon ointment. Of course, to maintain buoyancy, they must be fished with a floating, rather than a sinking, fly line.

There are various methods used to fish the dry fly. They are designed not only to keep the fly floating, but also to keep it floating as naturally as possible. For purposes of discussion, we will group these methods into two broad categories: the upstream method, and the downstream method.

Upstream presentation is the approach used most often by today’s dry fly fishermen. To some, it is the only way to fish the dry fly. Fishing in England, I was sternly informed that, regardless of where I suspected the fish to be, I must present my fly upstream of the fish. As a stately English gentleman told me, “It just isn’t done any other way.” As you shall learn, however, that is not necessarily the case.

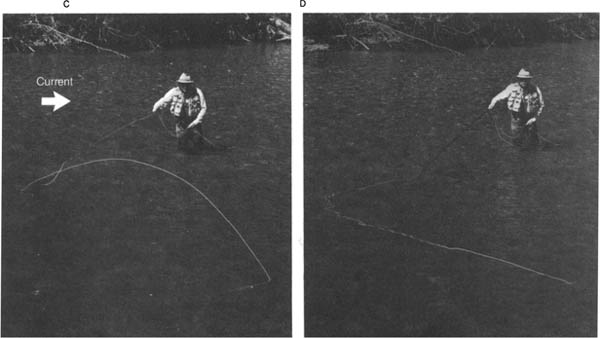

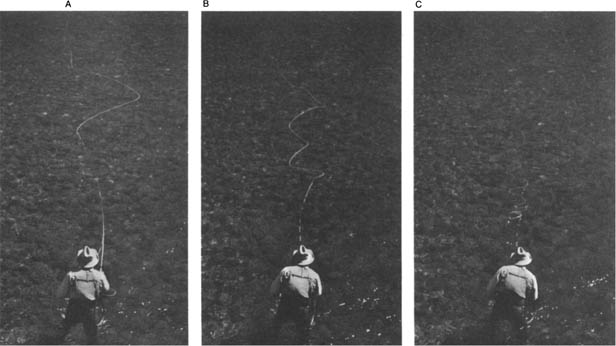

When fishing a dry fly upstream, be prepared for the line to start drifting back toward you the moment it touches the water. To avoid losing a fish due to such slack, you must retrieve the drifting line. First, cast (A). The moment the line hits the water, place the line you’ve been holding in your free hand over the index or middle finger of your rod hand (B). By pulling the line through this control point (C), the excess line can be efficiently retrieved.

True, there are several reasons, besides tradition, for using the upstream casting method. First, approaching a fish from below helps to keep us undetected. Remember, fish face upstream into the current to better intercept their food and to facilitate breathing. Also, multiple crosscurrents exist, which create fly drag, and the upstream method helps us to reduce that problem and facilitate the natural float of the fly.

Once you have taken a position in the stream and selected the area where you wish to drop your fly, cast up and slightly across stream, allowing the fly to land above the suspected lie. As the fly begins its float downstream, retrieve, or strip in, excess line by placing the line in the index or middle finger of your rod hand and pulling with the other. That is done so that if the fish does come to your fly you can strike quickly. Keep the fly floating as long as possible, even if it has passed the spot where you thought it would be taken. Remember, after the fly enters the fish’s window, the fish may follow it for some distance. This whole process may have to be repeated two and three times before the fish actually comes to the artificial fly.

Whether the cast is directly upstream, or upstream and slightly across, this technique is a tried-and-true method for fishing the dry fly. But there will be spots that can’t be reached or properly fished by casting upstream, particularly in very selective spring-creeks. In such cases the downstream method may be more useful.

There will be times when a favorable presentation position cannot be obtained by upstream casting. When peculiarities of the stream flow indicate, or because of delicate water situations, such as flats, a downstream cast may be your best method. Keep in mind that your movements are now much more distinguishable to the fish. Keep your distance. Make your normal cast to a spot above the target area, but instead of retrieving line, as in the upstream uproach, feed it out at a speed that will allow the fly to float naturally. Allow the fly to float for as long as possible; the fish may follow, and you don’t want to snatch the fly away from it.

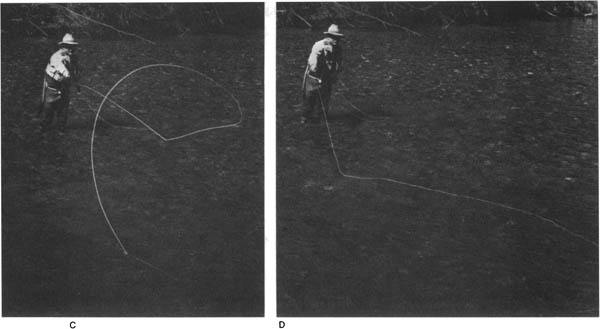

As the fly line extends out on the forward cast (A), wiggle the rod quickly back and forth (B), creating serpentines in the line (C). In the water, these serpentines slowly uncoil, allowing a natural downstream float to the target. To continue the float, pay out more line.

The use of a wet, or subsurface, fly is the oldest method in fly fishing; it was used to the exclusion of other methods through the mid-1800s. Today, its popularity has diminished, having fallen to the more exacting science of fishing imitation nymphs.

The wet fly itself denotes a particular fly pattern designed to imitate an immature, or drowned, winged insect that has arrived from land or by water. This differs from a nymph in that the nymph, a separate aquatic stage, is not yet winged and therefore has a completely different silhouette. The two fishing methods are often referred to collectively as “fishing wet,” and because the fly and the strike of the fish are not necessarily seen, but rather felt, different types of equipment and techniques are needed.

Wet flies, of course, carry more weight than the delicate dry flies. Absorbent materials tied on heavier wire hooks help the fly sink below the surface. Floating fly lines can be, and are, used for fishing wets, but the use of sink-tip and full-sinking fly lines of various densities can often help to sink a fly beyond the depths that it would reach with a floating line. Traditionally, rods used to fish wet were very soft so that they would quickly telegraph and also absorb the surprising, often jolting, strike of a fish. Today standard rods do the job well.

Once a wet fly is chosen, your first task is to determine the proper fishing depth. Remember, fish occupy places where the food comes to them. During a hatch, fish will typically locate themselves close to the surface where they can pick off the sub-aquatics as they begin to hatch, although at other times they will occupy a middle-depth position, intercepting drifting food coming off the bottom. When no hatch is in progress the fish will most often hold near the bottom of a stream where there is plenty of protection and little current. Your job, then, is to present the fly at the proper depth where the fish is located.

The quartering-down-and-across technique is a traditional method for fishing the wet fly. Because the line, leader, and fly, when swinging across the current, are very taut, the strike of a fish is quickly telegraphed to the angler. Also, the swinging fly appears to swim through the water, giving it a lifelike motion. For these reasons, quartering down and across is the method used most often by anglers of all abilities.

The cast is made slightly down and across stream. The current creates a belly in the line, which in turn swings the fly across the current to a final destination directly downstream of the angler. The fly is most often taken during the swing, and if it is not, the fisherman can twitch the rod, which will impart additional action to the fly.

Strikes can also occur while the fly hangs in the current below the angler, and they can be fairly abrupt. Thus, striking, or raising the rod tip to set the hook, becomes unnecessary; the fish will generally hook itself. Because fish are often hooked when the fly is in this downstream position, I have known many fishermen to forgo the cross-stream cast and swing, casting directly downstream and hanging the fly in the current. Although big fish are not often deceived by the latter method, it is the abrupt strike, so easily detected, that appeals to these fishermen.

This method is often referred to as the grease-line or Wood’s technique, (after its originator, Arthur Wood). Before the wet fly begins its swing with the current, the line is mended upstream, controlling the speed of the fly as it moves across the current. In this technique, you throw the fly slightly downstream and across. As the fly begins to swing against the current, roll an upstream mend in the line so the fly drifts at a more natural, consistent rate. You may have to mend two or three times before the fly reaches its final position downstream. Then you pick it up and repeat the process.

The dropper fly is an old tried and true method still very effective. Based on the adage that, if one is good, two may be better, a dropper fly is simply an additional fly tied into the main leader. Some people even tie a third fly on for good measure.

The first fly is attached to the main leader tippet. About 18 inches up the leader (and this can vary), another piece of monofilament is attached and a second fly is tied to it. For those who would like to try a third fly—although I found that it creates a lot of tangling—an additional monofilament can be attached another 18 inches higher on the leader. The dropper fly technique can be fished either down and across, or down and across with a mend, depending on the current.

The wet fly is not used as frequently as the more precise nymphal imitations. Today, fishing a nymph imitation is more or less synonymous with “fishing wet.” Because a nymph reacts differently in the water than any other fly, it requires different techniques to simulate its action.

A typical dropper-fly arrangement.

The nymph or larval stage of aquatic insects makes up the greater part of a fish’s diet. As we have seen, the adult stage lasts as little as a few hours out of an insect’s year-long existence, but the nymphal stage is available to the trout throughout the year, and is therefore a stage well worth imitating. The nymph has various ways of moving about in a stream, and our fishing technique must be adapted to that.

A nymph either crawls or swims near, or on, the bottom of the stream, and during hatching, it travels from bottom to surface, where it is at the mercy of the current. It is these movements that trout notice and respond to, and they can be imitated by the nymph fisherman using either downstream or upstream techniques.

This method is closely associated with fishing the wet fly but can work nicely with the nymph as well. By casting slightly down and across, the fly is allowed to swing with the current until it is directly below the fisherman. In actuality, nymphs do not swim or swing in this manner. The method works because the fly is first allowed to sink, and the current, pushing against the line, causes a rising motion of the fly, which simulates the natural upward movement of the nymph. As with the wet fly, once the fly is directly downstream, it should be held there a few seconds. The current will wave the fly in an up-and-down motion, closely imitating a swimming nymph struggling to reach the surface.

While this technique may fool some of the fish some of the time, the law of averages says that it won’t fool all of the fish all of the time, and almost certainly not the largest and smartest. Yes, it is a proven technique, and with it, you will always take your share of fish. But other methods will give you better odds.

Here, the object is to let the nymph drift, rather than swing, with the current. This technique more closely mimics a natural nymph. Cast across and slightly downstream. As the fly sinks and begins its drift, the belly in the line must be eliminated by throwing an upstream mend, slowing the fly. An additional mend should be made as the fly moves across the current, keeping the line from interfering with the fly’s natural float. The idea is to let the fly drift, instead of drag, through the water.

Developed by Jim Leisenring, one of the great Pennsylvania wet fly fishermen, this method takes the down and across and mend method and adds a twist.

Leisenring understood that the rising motion of the artificial nymph looks natural to the fish. As the fly, originally presented above the fish, reached the proper location, the fisherman, by lifting the rod, would impart an upward movement to the fly. This, as with other downstream methods, is particularly effective when fishing caddis pupa, which, you will remember, rise very quickly from the bottom to the surface. The technique is very simple but very effective.

Although the various downstream methods will catch an ample amount of fish, it is the upstream techniques, once learned by the angler, that, overall, will be the most productive. Cast upstream, the nymph imitation more closely resembles a natural insect.

Nymphs, when they break loose from the bottom, are generally at the mercy of the current. Helpless, they must drift along until they either reach the surface for hatching, or attach themselves to another obstruction. The fisherman’s challenge is to simulate this helplessness for as long as possible, and the continuous, or dead drift, method generally does the trick.

Cast the fly, quartering up and across stream. As the fly begins its downstream drift, retrieve the excess line from the water and throw an upstream mend in the line. This allows the fly to sink as deep as possible. When the fly is directly across from you, throw another upstream mend and continue mending as the fly moves downstream. The objective is to keep the fly as deep and unfettered in its drifting motion as possible. With this method, the fly will always lag to some degree, even with mending, some distance behind the fly line itself. If the fly is allowed to drift correctly, the strike will most likely occur when the fly is at its deepest point, or directly across from you.

This method is far and away the most effective technique for fishing a nymph. Because you are not casting across currents which can cause drag problems, the direct upstream method allows the fly to float downstream in a natural looking dead drift manner. Cast directly upstream, above where you think fish are holding. As the fly comes toward you, strip in the excess line. If you feel or see the line stop, strike immediately by lifting the rod straight up. (More on how to strike at the end of this chapter.) When the fly is five feet away, pick it up and quickly repeat, moving six inches over from the original cast.

Used most on spring-creek, or slow-water, streams where the trout is seen rising or is visible to the angler, this technique is much like fishing a dry fly. Cast above the trout and allow the fly to float into the window of his vision. Remember, you are working to one fish, not a general area, so the actual drift of the fly need not be longer than 10 feet. When your fly passes the fish, cast back upstream and repeat the process.

One of the most difficult things about fishing a nymph, especially upstream, is detecting the strike of the fish. It is for this reason that many fishermen are reluctant to fish wet, preferring the dry fly, with which all the activity is observable. The downstream, or wet fly, method helps, for the strike is felt, but it is still not as effective at catching larger, warier fish as fishing the nymph upstream. What often happens is that a fish takes and rejects your fly, but because there is so much line on or in the water or the water surface is so disturbed, the strike goes undetected.

To better detect the subtle take, consider using a surface indicator. Attached to the leader 24 or 36 inches above the fly, according to the depth you wish to fish, an indicator essentially acts as a bobber. When the indicator stops or is suddenly pulled under the surface, you should immediately raise the rod, setting the hook.

Indicators take many forms. In the past, some fishermen tied a bushy dry fly (without the hook) up from the fly, but today nymph indicators, because of their acceptance by anglers, have become sophisticated. Some fly line manufacturers place at the tip of the fly line a flourescent three-foot section that can easily be seen by the angler. The butt section of some leaders are now dyed flourescent for the same reason. Acrylic yarns, stick-on foam indicators, fashioned pieces of cork, and tiny flourescent plastic tubes that can be slid to adjust for variations in depth are all highly visible, whether on or in the water, and can all be effective. Because fishermen can “see” what is happening, the use of indicators has made nymph fishing an important way of taking fish. Remember, 90 percent of a trout’s feeding is done subsurface. The fisherman who is reluctant to fish subsurface is missing a big part of the sport.

As we have learned, once fish reach a certain size, they either supplement their diet with other fish or totally concentrate on them for their food supply. Tending to be rather lazy, big fish will expend as little energy as possible to obtain their food, looking for forage fish that are easy prey—slow-swimming, crippled, or dying.

A crippled fish has trouble retaining its momentum. Holding in one spot is a struggle. Its energy depleted, it will turn on its side and float to the surface. After regaining some of its strength it will quickly swim toward the bottom, searching for a secluded holding spot. This process will continue as the fish slowly loses ground and drifts downstream.

Oftentimes large fish will create their opportunities by swimming fiercely at a gathered group of minnows, stunning one or two, which can then be swallowed at leisure. Minnows congregate in the shallow water. When attacked, the congregation bolts out of the water, as though someone had thrown a handful of pebbles in. If you have ever seen big fish working baitfish in the ocean, you know how that looks on a larger scale.

Fishing a streamer or baitfish imitation is measured in the quality of the fish, rather than the quantity. Remember, you are now looking for larger fish, and, because their percentage of the population is small, you will have to be more persistent in your fishing.

The key to streamer fishing success is patience. In a mile section of a trout stream, perhaps less than ten percent of the fish population will feed on other fish. In addition, only two of the ten percent may have residence in the particular pool or run you have selected to cast your fly. Because big fish are known to feed only once in every three to five days, you very well may be fishing for only one or two fish within that area. For such a small, select group, you must have patience if you are to be successful.

I’ve known many streamer fishermen who rate the success of their days not in how many fish they have landed but in how many strikes they have had. A five- or six-strike day can be a great day, for these anglers know that, considering the size of streamer they were using, the size of fish that came to the fly very possibly would be in the trophy category. Let me illustrate. During one unusually warm fall, I fished the Yellowstone River above Livingston, Montana, and, after three full days of fishing, I could count my strikes on one hand. Discouraged, I contemplated moving to another river system, but elected to try one more run before leaving the area. On the fifth cast I hooked a beautiful six-pound German brown that made the entire three days a success. Moral: Without patience, you will never be successful in catching a trophy fish on a streamer.

Unlike fishing a nymph, where the cast and the drift are so important, fishing streamers calls for working the fly in such a manner as to mimic crippled fish. Rather than working in an upstream manner, you fish a streamer by working downstream from the head to the tail of the pool, making sure the fly is worked through all sections of the pool. There are various line retrieves and rod movements we commonly use to impart good action to the fly. Let’s take a look at a few.

In the direct left-hand pull, you cast the fly directly across stream, at first allowing the fly to sink. As it swings across current, strip or pull the line with systematic strips and continue doing so until the fly is directly downstream from you. The strike can come at any time.

In the rod pump retrieve, we are not retrieving line, but using the rod tip to give the streamer a darting action. After casting across stream, and as the fly begins to swing in the current, pump the rod tip sharply in an up-and-down fashion. Do so until the fly hangs in the current downstream of you. The darting action of the fly will mimic the movements of a fish that is unable to swim effectively.

I’ve found the pull and pump method to be especially successful on big water where long casts are made. Because an overabundance of line is in the water, simple retrieving of the line or the pump of a rod tip will not move the fly enough to give it the telltale erratic movement of a vulnerable fish. A combination of pulling the line and pumping the rod tip simultaneously will communicate more dramatic action to the fly. Cast across and slightly downstream. As the fly begins to swing, pull down on the line held in your left hand and simultaneously pump the rod tip up and down. Allow the line to slip slowly back up through the guides, and then repeat. This is similar to the first movement of double-haul casting.

I learned the technique known as “the crippled or panicked retrieve” from one of the legendary streamer fishermen, the great writer Joe Brooks. He used it both on big water and in the shallow, placid water of spring creeks. You cast across and downstream to either a feeding fish or a selected holding spot. As the fly enters the water, flick the rod tip up and down very quickly five or six times, causing the fly to skitter just underneath the surface and creating an erratic movement that often entices big fish to strike without much hesitation. Where you know a fish is present, you will have your answer right away. Either he will move quickly to the fly or he won’t. There never seems to be a middle ground. If there is no action, quickly cast to another spot.

Remember, in fishing a streamer you have to impart some erratic swimming action to the fly in order to be successful. This action will elicit the vicious strike so characteristic of big trout. If you are patient and willing to tie on the really big fly, you have as good a chance as anyone of landing the fish of a lifetime.

Now that you have learned a bit about equipment, how to cast the fly, where fish are likely to be, what fish are most likely to feed on, and some of the methods and techniques used to fish various fly imitations, it’s time to review the step-by-step procedures required whenever we’re about to fish an actual stream.

After donning your waders and rigging your rod:

1. Select a portion of the stream that will be productive, remembering the four stream types: riffles, runs, pools, and flats. Note the depth of the area and speed of the current and think about the casting, mending, and stripping techniques you’ll need to fish effectively.

2. Analyze your approach, following the productive grid method of fishing a stream. Predetermine precisely where you will start fishing and where you will end, and also where you will place your first and last casts.

3. Try to determine what the fish are feeding on by first observing what insects are on the water or flying about. If no apparent feeding activity is taking place, select a general dry fly imitation such as an Adams, Royal Wulff, or Elk-Hair Caddis, and consider using a subsurface imitation—a wetfly, nymph, or streamer—if the dry fly proves to be unsuccessful.

4. After selecting the fly, determine the best method for fishing the particular imitation that duplicates the actual movements of the insect.

5. Before casting, analyze the various current problems that may disrupt your presentation and fly drift. Try to anticipate problems and take corrective measures before they happen, to avoid fly drag.

6. Now, enter the water quietly and make your first cast.

Choosing the right fly, or “breaking the code” is a problem common to all anglers. But you can choose correctly if you follow a systematic approach.