Regardless of their ability, fly fishermen will always be confronted with problems in catching fish. Solving those problems can often be quite frustrating, so you must develop a troubleshooting technique that at least provides a systematic method for sorting out the problems in a logical manner.

Problem solving is really a process of elimination. We observe, and then we try something; if unsuccessful, we try something else. Slowly, we eliminate all the variables, hopefully working our way to a successful conclusion. This process is much like a doctor analyzing and curing an illness. He will first observe and then eliminate all the things that could not be causing the problem. He then runs tests to determine which of the remaining possibilities is the culprit. Knowing the cause, he can implement the cure.

In fly fishing most problems fall into three categories. First is presentation, or where we place the fly and how it reacts while on or in the water. Second is the fly itself. Does it simulate what the fish is presumed to be feeding on that day or what the fish is accustomed to eating? Finally, if both presentation and fly seem correct, you must turn to the leader.

With presentation, the angler’s concerns consist of where he is fishing the fly and how the fly is being displayed to the fish while on or in the water. Say that you have chosen a likely run of water but so far have had poor results. It’s time to ask yourself a series of questions to determine if presentation is your problem. Have you covered the water systematically? Has your system been such that the fish has not been spooked? (Remember the productive grid.) Are you sure of the fish’s holding area? Many times I have watched a fish feed on the surface only to discover that his actual holding spot is several feet from the rise form. By casting the fly around the rise you can assure yourself that the fish has actually seen what you’re offering.

Once you have covered all the productive water, and you feel confident the fish has seen your fly (with little or no result), you must then ask yourself whether the fly drifted naturally to him. Was there unnecessary fly drag? Perhaps you need to mend your line either upstream or downstream, depending on the line belly. If casting downstream, feeding line out may be all that is needed.

Generally, fly drag is quite obvious to the fisherman, but there are times when this factor will be far from clear. I remember angling over a fish during a very nice hatch, but without success. The fly imitated the hatch and, I thought, passed over the fish drag-free, but still the fish was not interested. Frustrated, I went back to the bank to consider the situation. When I reentered the water about ten feet upstream of where I had been fishing I presented the fly and on the first cast the fish gulped it down. I deduced that the problem had been a slight drag, which was discernible to the fish but not to me 30 feet away. Changing my stream position solved the problem.

Once you are convinced that the fly is being presented properly and that it has been seen by a fish, you can confidently move to the next possibility, that the fish simply doesn’t like what you’re dishing up.

Selecting the right fly can be the most important and troublesome problem to the angler. Regardless of how well the fly is presented, if it is not the right one it will be rejected. In solving fly problems overall, you must first try to isolate a fly profile that the fish is feeding on or is recognizable to the fish. These basic profiles include, in the order of their elimination:

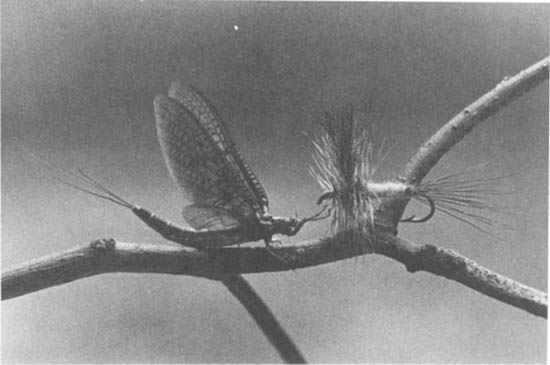

1) an upright dun or mayfly,

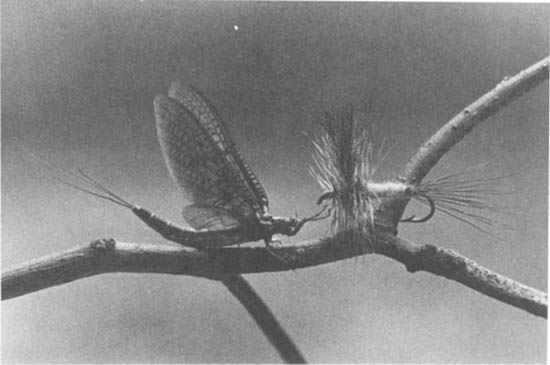

2) a downwinged fly of a caddis or stonefly,

3) a nymph,

4) a spinner, or spent winged fly, or

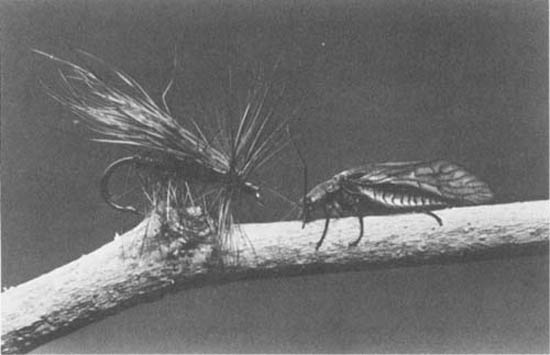

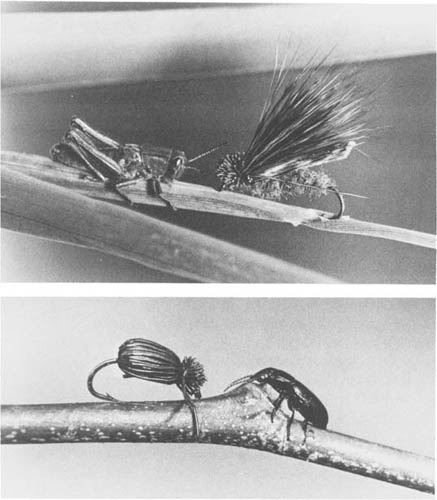

5) a terrestrial.

Yes, there are other insects of slightly different profiles, but by far these are the most common. Your next step is to determine whether you have a non-feeding or a feeding fish.

1. An upright dun, or mayfly.

2. A downwinged fly, such as a caddis or stonefly.

3. A nymph.

4. A spinner, or spent winged fly.

5. Two typical terrestrials.

Non-feeding or inactive fish are the most difficult to select flies for. Because there is no visible insect, there is no one fly you can isolate. Your procedure becomes a process of elimination, starting with an upright dun or mayfly and going through the various fly profiles until you find something of interest to the fish.

Although there is nothing sacred about it, the sequence of profile elimination should follow the progression mentioned above. Start with a conventional up-winged dry fly that most commonly imitates a mayfly dun. Next, move to a downwinged fly representing either caddis or stonefly. Moving on, try a nymph, then a spinner or spent winged fly, and finally a terrestrial type such as an ant, beetle, or grasshopper. Again, you are looking for something that is recognizable and of interest to the fish.

Getting the attention of the fish can take on many forms. Obviously, if more than one fish quickly takes your offering you can stop right there, but life is generally not that easy. It is when the fish either rises or strikes at the fly but at the last second rejects it by letting it slide on past, or jumps over it, or bats it about with his body, that you know the problem is not yet solved. Knowing that the fish at least likes something about it, your first move is to change its size, in most cases to a smaller fly. There will be times when a bigger fly is more acceptable, but that is not generally the case.

After you feel comfortable that you have exhausted all the size variables, you should then try the final imitation requirement, color. Color itself can be rather elusive, but if you have been fishing with a dark fly in various sizes with no results, try a lighter colored one. If this doesn’t work, move to a different profile and start the process over again.

When fish are feeding, you can discard the guessing game to some extent. Observe for yourself what fly is in the air or on the water. Capturing a specimen in your hand or with a net or in your hat can help you choose a close imitation. Problems arise when two or more types of insects are prevalent.

Let’s say a mayfly hatch is under way. Naturally, you select a proper profile imitation, matching both size and color. But there may be another, smaller mayfly present without your knowing it, or perhaps the fish has chosen the actual nymph as its target. Time to observe the feeding scene more closely. Also, in the midst of a mayfly hatch, a stonefly or small caddis could be depositing eggs on the water and the fish may be taking these, completely ignoring the mayfly. Such complexed hatch situations, as they’re called, present neverending variations and problems. You must be patient. Again, eliminating the variables should lead you to the correct fly.

If you have established that the fish is seeing the fly, that the fly is floating drag-free, and that a precise imitation has been selected, you must then open your thinking to the possibility that something more mundane and not terribly obvious is your problem—namely, the leader.

There will always be controvery as to whether fish actually see the leader or whether the leader tippet imparts microscopic drag not apparent to the distant angler. We know that both can be a problem. Unfortunately, many good fly fishermen think the leader tippet is totally unimportant, that only presentation and fly selection need their attention. But over my many years of fishing, I have proved to myself that tippet size is often involved in one’s success or lack of it. Let me illustrate.

Years ago, while fishing a famous spring creek, I had a very small mayfly hatching in profusion that eluded my every effort at imitation. The insect had a subtle yet irresistible coloration. Consequently, I concentrated my efforts on tying different hues in slightly varying styles. For about two weeks I had worked without success over three- and four-pound fish feeding on freshly hatched duns. A surprise was about to happen.

During this time a woman friend gave me some very fine transparent nylon sewing thread, which, on testing, appeared to be extremely strong. I tied a piece to the end of my leader, retied the fly, and presented the new package to the fish. Without any hesitation the fish took it. The problem had not been the presentation or the fly, but the size of leader I was using! I doubted that the fish had seen the leader because of my downstream casting approach, but the heavier leader was obviously setting up microscopic drag, creating an unnatural movement of the fly in the delicate-water situation. This microscopic drag was not observable to me 30 feet away, but it must have been highly visible to the fish inspecting it from one inch away.

Many people, for fear of breaking off a big fish, use leader tippets that are too large. When I hear their explanation, I emphasize to them that fish breakoff is secondary to their problem; what is primary is that the fish gets hooked in the first place. If you can’t hook him, you’ll never have a chance to land him.

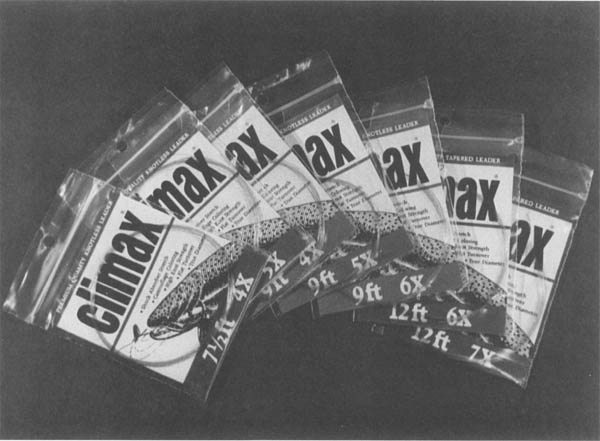

Smart fly fisherman always carry an assortment of leaders of different diameters with them when they go on stream.

Problem solving on the stream is an important aspect of fly fishing. It is a skill that is developed over time. The key is to be systematic, isolating and eliminating those variables that don’t point to the problem. These problems can be extremely complex, taking up the better part of an entire fishing season in finding the solutions. But if you patiently adhere to an established process of elimination, concentrating first on presentation, then on the fly, then on the leader—you will almost certainly solve your problem. Moreover, you will acquire a skill that will greatly enhance a day’s fishing on any body of water.

The author hooks an 18-inch rainbow trout on Silver Creek. Note the position of the rod and hands: up to keep the line tight and the hook in place.