Spring creeks, or flat, slow-moving waters, present the most difficult and challenging fishing situations for all fly fishermen. Because of the complex insect populations, the very slow, gin-clear water, and the often highly sophisticated, selective fish, many anglers avoid spring creeks altogether. I have seen many fishermen commence the cocktail hour at eleven in the morning, rather than the traditional five in the afternoon, after becoming mystified to the point of despair by the complex hatch and feeding activity characteristic of this water. Still, spring creeks offer large fish and tremendous challenges, and for both these reasons, they are the classic fly fishing waters.

“Spring creek” is a generic term describing a type of water known in England as a “chalk stream,” and in the eastern United States as “limestone waters.” Because the creeks’ main source of water is underground, water temperatures remain constant, creating an ideal environment for both aquatic insects and fish. Also, the large underground aquifers that feed spring creeks contain a great deal of the limesalts that create high alkalinity, so important to stream life. Huge weed and grassbeds flourish, which, in turn, harbor great populations of insects and offer protection for fish. Compared to streams of more normal alkalinity, the creeks’ insect populations are enormous, in terms of types of species as well as in sheer numbers. Spring creeks are literally insect factories in which the resident fish grow to be both large and selective in their feeding habits.

There are additional factors that give spring creeks a special mystique. Though in places they may resemble freestone streams, with pockets, pools, and runs, for the most part spring creeks consist of flat, slow-moving water. Because the water moves at a snail’s pace, fish have ample time to examine your offering, determining whether the fly adheres to the fish’s present feeding interests. If it doesn’t, you don’t catch fish. Your fly, therefore, must be a more exacting imitation than is needed on other types of water.

Finally, fish tend to lie fairly close to the surface when surface-feeding in spring creeks. In these instances, the cone-shaped window through which the trout views its food is quite small, maybe only four to six inches in diameter, and the fly must be presented precisely where it will float over the fish, thus adding to the angler’s problems.

The quality of a spring creek is not necessarily measured by the quantity of fish you catch; it has more to do with the fascination of meeting a challenge with your wits and skill. Even though spring creeks are difficult to fish, the problems encountered can be overcome as long as you approach them intelligently and systematically. You must understand insect hatches and present the appropriate fly selections.

Spring creeks offer a buffet of food for fish. Other than the apparent mayflies, caddisflies, and small midges, they harbor good populations of damsel and dragonflies as well. Crustaceans, such as fresh-water shrimp, crayfish, sow-bugs, backswimmers, and the like, add still another dimension to the smorgasbord. Moreover, each stage of each species represents a different kind of feeding opportunity that the fisherman must be aware of. A basic understanding of entomology is essential.

As I have mentioned, slow-moving water necessitates a more precise selection of fly imitation. The size, profile, and color of the fly need to be exact; they should not be compromised if you can help it. Since the flies must be tied with such precision, the use of hackle, or the wrap feather that gives our conventional dry fly patterns such a fuzzy appearance, must be kept to a minimum or in some cases avoided. Body and wing outline are extremely important on flies used for spring creek fishing, and hackle can distort the profile of the fly. Fly-pattern styles such as compara dun, thorax types, and parachute flies (where the hackle is tied horizontal to the hook, versus perpendicular), work well. But it is the no-hackle flies, popularized by Doug Swisher and Carl Richards, that in my opinion are the most effective types used on spring creeks today.

The following is a fairly complete list of fly patterns that will duplicate most fly hatches on spring creeks throughout the United States and various parts of the world. Many hatches are similar in coloration but different in size; I have listed the basic color patterns. If purchased in a variety of sizes, these flies should meet the various spring-creek fishing criteria. Note also: Two basic fly styles are listed, no-hackles and thorax type, for the purpose of availability. Depending on where you do your fishing, one or both styles should be available. Remember, local assistance is invaluable.

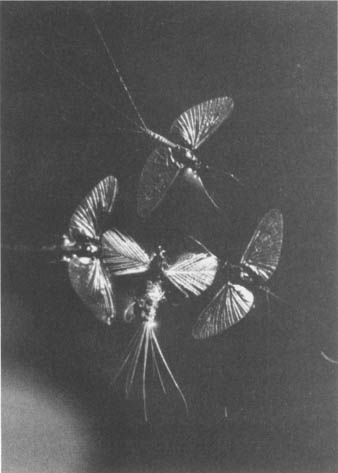

Some spring creek hatches are so dense, that the chance of a trout taking your imitation are nearly impossible. In this photograph, a cloud of Tricorythodes, or “trico,” as they are commonly known, has reached the spinner stage and is about to hit the water.

Because spring creek water is so clear and the food so abundant, fly imitations must be more exact than for most other fly fishing situations. There is a trico imitation in this picture. Can you find it?

Spring Creek Fly Assortment

Gray/Yellow No Hackle, #16, #18, #20, #22

Slate/Tan No Hackle, #14, #16, #18

Slate/Gray No Hackle, #16, #18

White/Black No Hackle, #20, #22, #24

Brown Henspinner, #14, #16, #18, #20, #22, #24

Yellow Henspinner, #16, #18

White/Black Spinner, #20, #22, #24

Pale Morning Dun Emerger, #16, #18, #20, #22

Gray Thorax, #14, #16, #18

Olive Thorax, #16, #18, #20

Pale Morning Dun Floating Emerger, #16, #18

Pale Morning Dun Floating Nymph, #18

Brown Ephemerella Nymph, #12, #14, #16, #18

Mason Beatis Nymph, #16, #18

Partridge Caddis, #14, #16, #18, #20

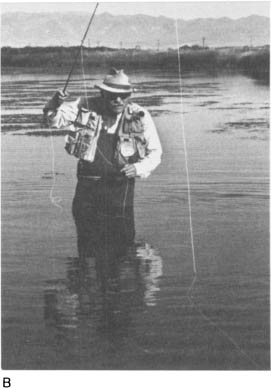

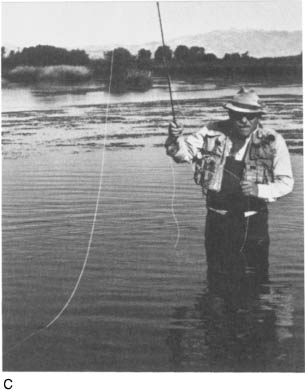

Precise fly imitations are needed, but good fishing approach is equally important.

The approach to spring creek fish is much like a safecracker’s approach to a safe. You must be delicate and careful, moving slowly, and closely observing the situation in front of you. Because spring creek water is not “readable” in the sense of riffles, runs, and pools, you generally locate fish by looking for feeding activity. Spring-creek fishing thus becomes a hunting and stalking operation, where you spot the prey and then make your stalk to take it. Pick one fish and move very carefully toward it, for disturbances in this water will not only cause it to stop feeding but can “put him down” (off feeding) for the remainder of the hatch. Wading through the water as though you were late for dinner will only spell disaster. Once you know the fish’s whereabouts, you must maneuver into a position to cast to it.

Traditionally, it has been thought that the upstream cast is solely associated with fishing the dry fly, regardless of what type of water you are on. It’s true that in fast water, upstream casting helps minimize fly drag and places the angler below the fish’s area of perception, but in spring creeks the conventional upstream cast is likely to be unsuccessful. Why? Because the first thing the trout views of this cast is not the fly, but the leader. What to do? By maneuvering himself upstream and at a 45-degree angle to the fish, the trouter can present the fly and allow it to drift downstream, ahead of the leader, making it more acceptable to the trout. Whether or not the fish actually sees the leader remains a topic of controversy, but we do know that presenting the fly in this manner is far more effective than the conventional upstream approach. Remember: fly first, not leader first.

Before making your cast, stand for a moment and watch the feeding characteristics of the fish. Some fish will hold and feed in one position, while others will move from side to side and/or upstream and down. Look for the fish’s feeding pattern and present your fly accordingly. If you don’t and the fish is rather active in its feeding movements, a mispresented fly can be trouble. Let me give you an example.

Fishing with a customer one day, I approached a very large rainbow feeding on small mayfly spinners in a very shallow backwater where the current was nonexistent. The fish’s feeding pattern was distinctive. It would start at one end of the backwater and slowly make its way upstream, sipping the small naturals as it went along. Upon reaching a certain spot, it would turn downstream, swim back to its original starting position, and repeat the process. Knowing that in the shallow clear water a poorly laid cast would be detected during the fish’s upstream movement, we waited until it turned away from us and headed for its starting position before we made our cast. On our fourth presentation, the fish made the mistake of taking our offering instead of a natural. The fish would never have been hooked if we had not first watched and analyzed the situation before casting.

In spring creeks, there are a multitude of current changes, most caused by the weedbeds abundant in these waters. Since the drift of the fly is crucial, and since several different currents can exist between you and the fish, you need to present your fly in such a manner as to produce slack in both line and leader so that the fly itself is not affected by these extraneous water movements. Remember, you are fishing to one fish, not an entire holding area; therefore, the float of the fly must be absolutely natural, covering not more than ten feet.

Fly casts that create slack line go by many names—the pile cast and the hesitation cast, to name two—but they all have the same goal: to pile the leader on the water surface so that while the fly journeys downstream to the fish the leader unravels quietly, creating a natural float. To create this slack while casting, stop the rod abruptly at the end of the forward cast (11 o’clock). This causes the line and leader to bounce back much like an elastic band, and the leader to fall to the water in serpentines, or on top of itself.

Because the amount of coiled leader can vary from cast to cast, and because the fly should be kept from dragging before it reaches the fish, you must also feed out additional line as the fly makes its way downstream. To do this, quickly flip the rod tip up, which will propel the line through the guides and out onto the water. Feeding line must be done before the drifting fly runs out of coiled leader. Therefore, as soon as the fly begins its drift, start feeding more line.

Your overall intent should be to place the fly in a direct line above the fish, but even the most expert of anglers sometimes miscast. Fortunately, however, we can maneuver the fly into the proper position. In many cases, fly casts are too long, going beyond our target area. To bring the fly into proper alignment to the fish, all you have to do is lift the rod tip very slowly, and actually drag the fly into position. Once it’s where you want it to be, quickly drop the rod tip and begin feeding line out until the fly reaches the fish. Not only does this technique eliminate visible coiled leader around the fly, it also realigns the fly for the proper drift line to the fish, which is equally important.

Spring-creek fishing is really a hunting, stalking, and, oftentimes, a waiting game. After isolating a feeding trout, quietly maneuver yourself upstream of it so that it is in a quartered downstream position (at a 45-degree angle) to yourself, and plan on casting to a target four to eight feet above it (A).

Make your cast, stopping the forward part of the movement at the eleven o’clock position (B). This causes the line and fly to jerk back, creating slack for the fly’s drift to the fish.

After the forward cast touches down, keep the rod tip high (C). Then . . .

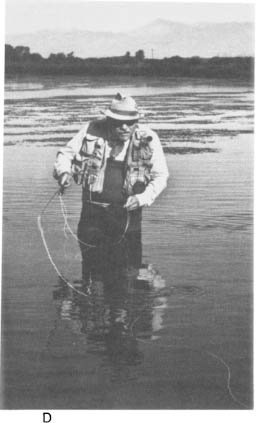

. . . very quickly drop the rod tip down, almost to the water’s surface (D). This piles additional line on the surface, ensuring the fly’s continuous, drag-free drift to the fish.

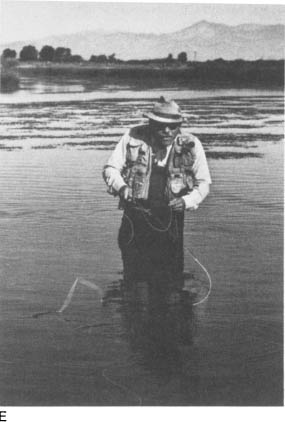

You can also feed out more line for a drag-free drift by shaking the rod tip up and down, or from side to side (E). Never let the water current pull out additional line; that can only lead to drag.

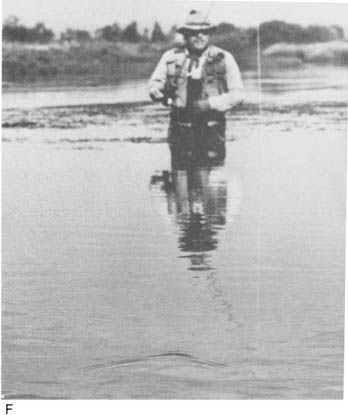

If the cast goes beyond the intended target, very slowly lift the rod tip and carefully drag the fly to the proper position (F). Now quickly drop the rod tip, feeding out line before the fly reaches the fish’s window.

What I have discussed is the basic approach to presenting a fly to a fish on a spring creek. So that it becomes perfectly clear, let’s review in sequence the necessary steps for fishing success.

Assuming that, by observation, including netting or scooping insects, you have chosen a fly that meets precisely the requirements of size, profile, and color:

1) Select one fish worthy of your efforts.

2) Carefully and quietly maneuver into a position where the fish is at a 45-degree angle downstream of you.

3) Watch the fish’s feeding habits, determining whether it is moving about or is stationary.

4) Pick a spot where you wish the fly to land above the fish.

5) Make your cast, but stop it abruptly at 11 o’clock on the forward cast, causing leader to pile up on the surface.

6) If the cast is too long, lift the rod tip, slowly dragging the fly into position.

7) As the fly begins to drift toward the fish, feed line out by quickly flipping the rod tip.

8) If the fly is not taken, allow it to drift downstream beyond the fish before picking up and recasting.

Once again, remember, you are fishing to one particular fish. The fly’s float distance is no more than eight or ten feet, with the fly first presented five to six feet above the fish and allowed to float on another four feet or so beyond him before it is removed from the water and recast. Strive for as little water disturbance as possible. Also, don’t give up on the fish after only one or two casts. If you have selected the right pattern, if you have made the proper presentation and drift, and, if you are persistent, you will be successful.

Successfully deceiving a selective trout in a spring creek is one of fly fishing’s greatest satisfactions.

Spring creeks dictate a bit more thought on equipment needs than one would use on the average river, a requirement sometimes overlooked even by accomplished anglers. In general, spring creek rods, reels, and leaders are more delicate and precise.

The emphasis placed in choosing the average fly rod is on fly casting, with little attention given to its fishability. Since flat-water leader tippets are very fine, ranging from 5x to 7x in diameter, your spring creek rod should be relatively soft so that it can absorb the strike and run that large fish make on these gossamer leaders. In addition, fly line should be chosen not only to match the soft rod’s flex but also to minimize unnecessary water disturbance when it lands. Fly line should be within the three-to six-weight category. Heavier weight lines are totally unnecessary and often detrimental to your fishing. Finally, because the leader tippets used are so delicate, a smooth-running reel with a fine adjustable drag helps to protect from breakoffs.

The quality of spring creek fishing is not necessarily measured in the quantity of fish you catch; it has more to do with the fascination of meeting its special challenge with your wits and skill. I can tell you that the challenge is great and the rewards even greater. They represent the classic in dry fly fishing and may very well be the ultimate in the sport.

Don’t restrict your angling to streams and rivers. Good trout can also be taken on cold-water lakes and ponds.