Many people think of fly fishing as restricted solely to streams and rivers. But because lakes and ponds offer quantity, variety, and many times very large fish, including trout, they present fishermen with fine opportunities to expand their angling experience. Consequently, lakes should be on the must-do list of any fly angler.

There is something mysterious about a lake. What lurks in its depths is a question that excites the imagination. Sinking a fly through the lake’s various strata, retrieving it, and feeling the unexpected strike of a fish, I come to realize that fishing a lake can never be boring: the allure of the unknown is always there.

To fish lakes successfully, you must understand their aquatics, structure, and depth. Because lakes are different from streams, featuring a distinct aquatic environment, you must also alter your fishing technique, equipment, and angling thought.

Conventionally, lakes are divided into two categories, highland and lowland types. The differences in elevation mean differences in both the types and the quantity of food in them. Lowland lakes, up to 6,000 feet, are generally the most fertile, containing the greatest array of aquatic food sources for fish. Higher in altitude, especially above 10,000 feet, aquatic life dramatically diminishes and becomes very specific to the region.

With their insect diversity, lowland lakes are often more productive than high lakes in terms both of numbers and size of fish. Often, immense populations of insects are fed upon by the fish during all stages of their development, offering a smorgasbord of food for fish. In addition, leeches, various crustaceans including freshwater shrimp, and, of course, other fish further enhance the diet. Although the mayfly and caddisfly are found in all types of waters, including lakes, there is a host of food types in the lake’s ecosystem that can be preferable to the fish. Slow-water species, such as midges, damselflies, dragonflies, leeches, and shrimps, are some of these.

Midges are one of the most important contributors to the food chain in both lowland and highland lakes. In fact, where waters are very cold, the midge may be the predominant aquatic insect. That is certainly the case in cold regions such as northern Canada. Fish eat all the various midge stages, from larva to adult; therefore, if you intend to fish Northern lakes, you need to carry representative patterns.

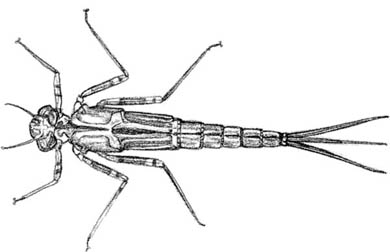

Damsel and dragonflies are among the more significant insects on lakes and ponds. Most of the time these flies are fished imitating their sub-aquatic, or nymphal, form—the adult stage of these insects is not often available to the fish, which makes a surface, or adult, imitation unnecessary.

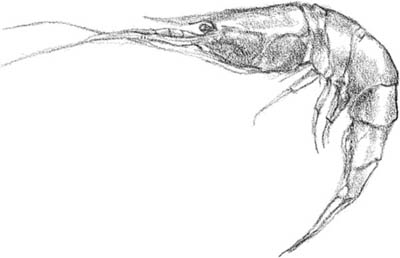

Leeches and crustaceans are also greatly prized by lake fish. Leeches are universal, and, because of their quantity, fish feed on them readily. In addition, freshwater shrimp (crustaceans) are an important and common food source. In some lowland lakes, it is not unusual to find populations of 200 to 500 freshwater shrimp per square foot. Anglers should carry several patterns to imitate each of these food sources.

The above insects and crustaceans tend to be the primary food sources in lakes and ponds, but they are certainly not the only edibles available. Very large fish have very big appetites, and forage, or baitfish, are the most obvious way to satisfy their needs. Consequently, if trophy-size trout are your objective, fishing various streamer imitations is often a good bet, regardless of the lake’s altitude.

As you move higher into the mountains, insect diversity diminishes, making fishing frightfully difficult or sinfully easy. Only one or two specific insects may be present, and exacting fly imitations are often needed to seduce the selective trout. The opposite can also be true: Anything that falls to the water may quickly be devoured by the undernourished fish population. In general, observe what is on or in the water for a clue to local feeding. Shoreline debris is also a source of information. High lakes can be fickle, but, because of the location, are a delight to fish.

Midges.

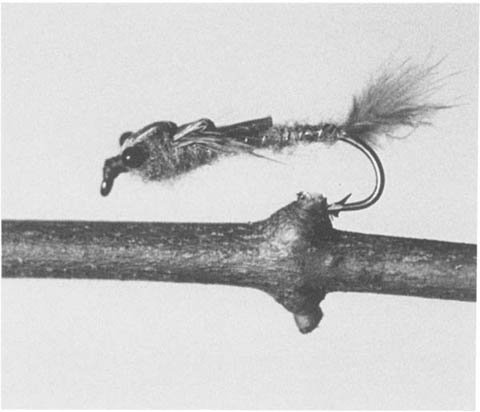

Midge imitation.

Damselfly nymph.

Damselfly nymph imitation.

Leech.

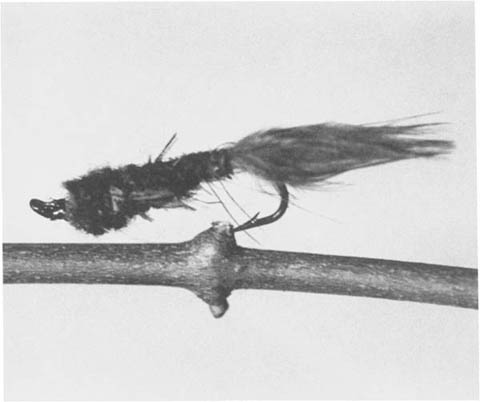

Leech imitation.

Shrimp.

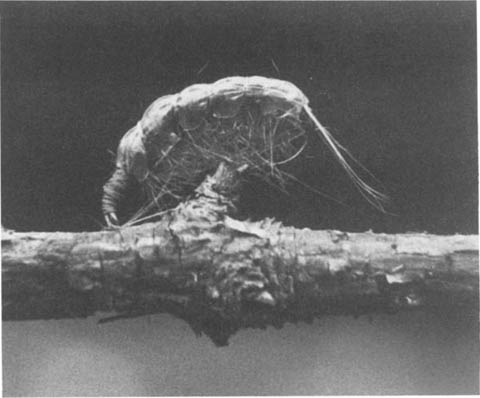

Shrimp imitation.

Food sources are important, but, as on all fishing waters, if you don’t know where to place your fly, you may be the world’s greatest entomologist and still fail.

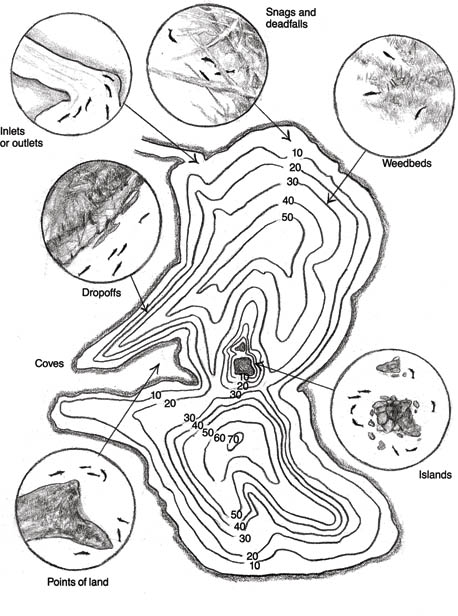

At first glance, lakes and ponds give very few clues as to the whereabouts of the fish. Unless fish are actually rising, the smooth, expansive surface serves to conceal the underwater topography, making the entire impoundment appear to be a vast, unreadable wasteland. Streams are made of runs, pools, riffles, and flats, all of which say something definite about fish lies. To the inexperienced fisherman, lakes do not have these obvious signs. Yet they do have other characteristics that can actually be read as easily as a stream. Let’s look at a few of the more distinguishable places in which fish will be located.

Drainage lakes are by far the most productive and also the most abundant of the Stillwater fisheries. Water inlets arrive from streams, providing plentiful spawning areas, additional food supplies, and fresh oxygen. Therefore, inlets and outlets, if present, are among the first areas you should fish in an impoundment. Fish congregate around these spots, and they should be fished extensively.

In lowland lakes weedbeds are very important. As altitude increases, weedbeds thin out. In the very high lakes they are often nonexistent. As you might suspect, weeds harbor aquatic insect life, and fish like to be close to their food sources. When fishing weedbeds, place your fly on the edges, holes, or channels of the beds, making it more visible to the fish.

Just as in streams, fish have a natural liking for depth changes, often referred to by bass fishermen as “structure.” Where the geomorphology of the lake is altered there is an ideal place for fish—and for the fisherman to place his fly.

In shallow lakes, drop-offs are easily spotted. But in deep water there are some anglers, especially the bass fishermen, who use sonar depth finding equipment that aid the fisherman in discovering the underwater structure. Although I am not a confirmed advocate, these instruments not only map the lake bottom but locate schools of fish as well, which does help explain some questions about fish location.

Another classic drop-off situation is the location of the old streambed if the lake is manmade. Fish will always hold in these areas.

Small islands are another important area near which fish will hold. Aquatic insects congregate in the shallows, thus providing an irresistible food source for the fish.

Where land protrudes into the lake, fish will congregate. A point of land is actually a depth change. A point does not stop at the bank but extends under the water for some distance, making for a depth change situation on either side of the point. Fish that reside near jutting points of land enjoy the advantage of both depth and any food supplies migrating to these areas.

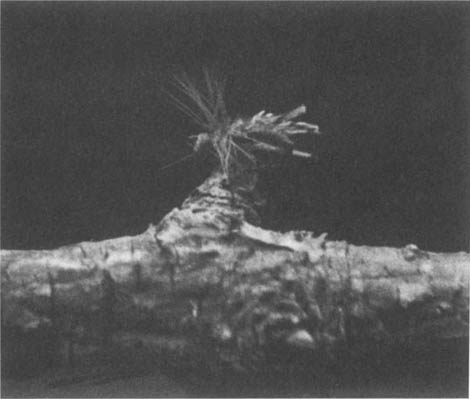

Deadfalls are found in all lakes but are extremely important in high mountain lakes. They provide overhead protection for cruising trout and harbor-clinging aquatic insects. I think I’ve never visited a high lake where I didn’t find one or two fish hanging around shoreline deadfalls. Deadfalls can be a nuisance for fishermen because of snagging, but don’t pass them up.

Coves are generally the shallowest places in lakes and invariably have the warmest water. In the early part of the season fish will congregate in coves because they are among the first places insect activity will be found. Throughout the season, I always look for rising, feeding fish in these areas, for as a rule, fish cruise through coves looking for easy prey.

Springheads are extremely important to all Stillwater fisheries, especially if they are the main source of a lake’s or pond’s water. The constant temperature and fresh oxygen supplied by the underground water help provide an ideal environment for fish. But because they are subsurface, springs are often difficult for fishermen to locate. Listening to other anglers who may have stumbled onto a spring is always a good way to get information. Bubbles coming to the surface are another indicator of an underground water source. Also, because spring sources deposit white calcium in the area of the springhead, there will be distinguishing white marks nearby. You can also take temperature readings. General lake water is 60 to 65 degrees; a spring will be closer to the 50-degree mark or colder.

Typical holding areas for trout in a lake include, clockwise, top, snags and deadfalls, weedbeds, islands, points of land, coves, (including dropoffs and springheads), and inlets or outlets. Studying the topography around a lake can yield further clues concerning trout whereabouts.

A good rule to follow is this: If you find a spring, fish the area hard.

Cliffs and rock faces are generally the deepest shoreline parts of lakes and ponds. The crevices in the rocks harbor both insects and baitfish, so that fish of all sizes cruise these areas. The shadows shed by the rock and outcroppings along its face also provide shelter available nowhere else in the lake. You should always fish near these outcroppings.

There will be times when the lake or pond will show no inlets or outlets, snags, points of land, islands, or visible drop-offs. What do you do then? Look to the land around the lake, for it might give you clues as to what is happening underwater.

Visualize the continuation of whatever landmarks there are extending under the water from the lake’s shoreline. Draws and undulations at the lake’s edge are indicators of possible underwater drop-offs. These might be your best clue to where the fish will lie. In general, try to visualize the lake in cross-section.

It may sound odd even to mention that if you find surface feeding fish you should cast your fly to them, but for some reason I have seen countless fishermen ignore this obvious sign and pursue other kinds of areas. Don’t miss your chance. The fish are solving a very important problem for you: location. There is no need to guess.

The areas discussed above are not the only ones fish will hold in lakes, but they are the prominent ones. Now that you have a better idea of the fishable topography of a lake, you need to address another important factor, the depth at which fish hold.

The ecosystem of a lake can be complex. The productivity of a lake is measured in terms of its ability to retain oxygen, its layering of solar energy for photosynthesis, and its temperature ranges.

Like all creatures, fish seek the most comfortable place or depth to reside, where they will have the most advantageous mix of the elements that are vital to their survival.

Lakes have three layers that are significant in understanding where fish will be: the epilimnion, the thermocline, and the hypolimnion. The top layer, the epilimnion, can be as little as a few inches, extending down to as much as 60 feet. Because the water temperature in this layer is generally too warm for comfort, fish will not reside here. The middle layer, the thermocline, is the stratum most fish seek. Beginning anywhere from a few inches to the rare depth of 60 feet below the surface, the thermocline is generally only three to ten feet thick but contains the optimum combination of oxygen, temperature, and light penetration. The bottom layer, or hypolimnion, may be quite thin, only a few inches up from the bottom, or thick, extending upward to meet the more ideal level of the thermocline. Regardless of thickness, though, the hypolimnion is unlikely to hold fish because of a lack of oxygen and unsuitable temperatures.

It should now be obvious that, in addition to understanding the most likely physical habitats for fish, you need to discover the depth at which the fish are concentrated. To ignore the layering aspect of the lake environment is to limit your degree of success. When you fish a lake your main objective is to place yourself where the fish are. The fish are there and if you can find the spot, you will catch them.

The feeding habits of lake fish can lend themselves to either surface or subsurface fishing. There are times for both, and it is up to the angler to analyze what is happening and use the appropriate method based upon the situation.

Dry fly or surface fishing is obviously appropriate when the fish are feeding on adult insects in or on the surface film. Because there is no current, the fish swims to the fly, rather than waiting for the fly to drift to it. Therefore, after selecting an appropriate imitation, you must determine the direction the fish is moving and make your cast ahead of it, leading it slightly. If you cast directly at a rise form, you stand the chance of either spooking the fish or placing the fly where the fish was, not where it is going. Watch for dorsal and tail fins to indicate direction.

You’ll need a floating fly line, and the dry fly you select is just as important as when you are fishing rivers and streams. Analyze what is on the water and make your choice using the same imitation requirements you always use—size, profile, and color.

Fishing the dry fly is fun and exciting, but to most serious lake fishermen, fishing the underwater stage of the insects and other life forms is not only the most important but also the most productive method. It is often said that 90 percent of feeding in a stream is done beneath the water’s surface. In a lake the figure may be closer to 98 percent. I have even seen anglers who know this fooled into thinking that the fish were surface feeding when in actuality they were feeding on nymphs just below the surface. What happens is that the upward momentum of a fish chasing down its prey creates the apparent rise form that is typical of surface feeding. Fishing subsurface imitations is so prevalent in lakes and ponds that even I, a professional fisherman, have trouble remembering the times when I have actually used a dry fly.

In using a subaquatic imitation (except in shallow lakes or for near surface-feeding fish), you must first change your fly line from a floating to a sinking type, tie on the appropriate nymph or subsurface imitation, and then try to determine at what depth the fish are feeding, or where the thermocline layer is located. To do this, sink and retrieve the fly at various depths until some action or response by the fish occurs. Either start at the surface and work down, or vice versa. Employ a counting method (“One thousand one, one thousand two,” etc.) to identify the proper depth for future casts.

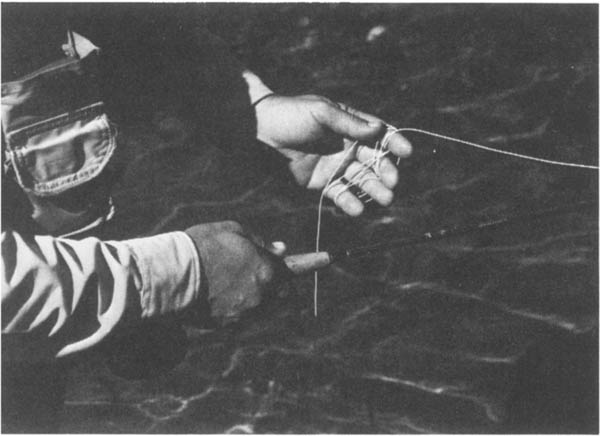

Ideally, you want line, leader, and fly to sink at the same rate, but that seldom happens. The leader is not of the same density and therefore lags behind the sink rate of the fly line. To counter this problem your flies should be weighted, allowing at least the fly and fly line to sink at the same rate. To further remedy the leader problem, use very short leaders, no more than three to six feet in length.

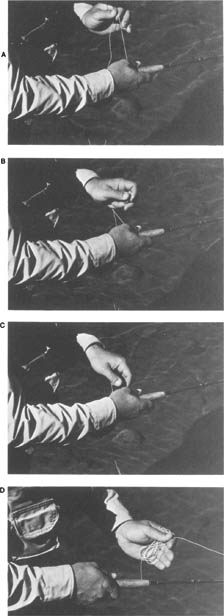

Once the fly has reached thé desired depth, it is time to retrieve the line, mimicking the swimming motion of natural insects or fish. With the rod tip extended downward, into the water, first make one or two long retrieves, or pulls, of the line, making sure, as you do so, to press it against the rod handle with the middle or index finger of your rod hand. These first long strips will straighten out most of the irregularities that might have developed in the line, leader, and fly during their descent. After you straighten the line, your retrieves should follow one of several patterns designed to make the fly mimic natural movements.

This is a useful slow retrieve when fishing nymphs in either lakes or streams. Use the thumb and finger (A), to gather line in the palm of the hand (B). Repeat the maneuver by dipping and lifting the hand for more line (C). Once you’ve gathered four or five coils (D), drop them to avoid tangles and continue the retrieve.

This popular finger retrieve should be used with caution since removing the line from the fingers can be difficult, and in salt-water fishing, where the fish can be large and powerful, the angler risks injuring or even losing a finger if there’s a strike.

The most common retrieve is rhythmic: a series of even-length pulls that make the fly swim or dart like a lively insect. Another popular retrieve is to strip the fly five or six times and then stop, which lets the fly settle as insects often do. To make the fly swim slowly, rather than dart, there is also the overhand, or figure eight, retrieve where the line is gathered slowly into your left hand. No matter which retrieve you use, if strikes don’t come, try varying the speed of the retrieve. Speeding up will often produce strikes. Yet, at other times, you must use a very slow retrieve to get results. Remember, the fly must look natural, it must swim. If the fly is allowed only to sit, it will never produce a strike from a fish.

No hard and fast rule governs your choice of gear for lake fishing. There will be times, especially in small ponds, when delicate fly rods will be more successful, but for the most part I like to fish lakes with a rod slightly more powerful and longer than one I would use for a normal stream. A rod eight-and-a-half to nine feet, handling at least a seven-weight line is usually a good choice. The more powerful rods are better for making longer casts and for fighting the larger fish often found in impoundment.

Even more important in lake fishing is your choice of fly line. I prefer a weight-forward fly line to a double-taper—once again for its ability to cast greater distances. It is imperative that you reach the fish. Nothing is more frustrating that to find yourself casting ten feet short of where you know the fish are. Besides a floating fly line, I like to carry both slow- and fast-sink lines for fishing the various depths of the lake. High-density, or extremely fast-sinking, fly lines usually are not necessary and can be detrimental. Remember, it is important not only to control the rate of sink, but also to be able to fish the fly at the depth where the fish are located. Therefore, over the years I have found a slow-sinking line the best. It allows the fly to remain at a particular level for a long time without sinking beyond it.

A general, single action trout reel is more than adequate. Make sure it has enough line capacity to handle a very large trout. At least 100 yards of backing may be required, and small reels simply won’t do the job. I’ve had fish run 150 to 200 yards in a lake. Without sufficient reel capacity and adequate backing, I would have lost them.

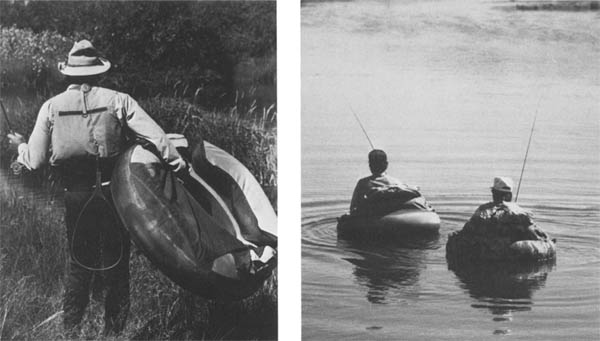

People fish lakes in different ways. Those who backpack into high mountain lakes are pretty much restricted to wading from shore. Those who can drive to their destinations may use floating devices, either boats or the now very popular float tubes.

In the past 15 years float tubes, or belly boats, have captured the fancy of the fishing fraternity. Today, they are manufactured far and wide, with innovations designed to provide comfort and convenience while fishing. They come with back rests, which also act as backup floatation for emergencies, big pockets for carrying fly boxes, aprons to collect fly line as it is stripped from the reel, and rodholders.

Quite safe, float tubes were involved in only one death that I know of, and in that case it was cardiac arrest that ended the fisherman’s life before the tube tipped over. Indeed, it is probably accurate to say that float tubes are at times safer than boats, especially when an unexpected storm materializes. Float tubes will ride the swells, while a boat can easily be swamped. As an added protection (and some states now require it), you can wear a flotation vest.

Float tubes.

Float tubes, or “belly boats,” provide anglers access to places in lakes and slow-moving deep streams unavailable to them by wading. Too, they afford anglers a lower profile in the water than do boats or wading.

Fishing in lily pads for bass and other warmwater species often requires pinpoint casting technique.