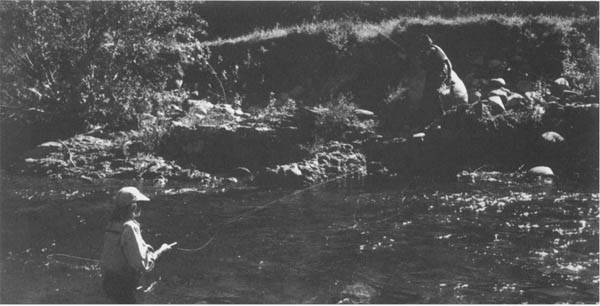

The sport of fly fishing is often thought of as a gentlemanly endeavor, pursued with respect for both the surrounding environment and the fish themselves. In addition, the fly fisherman takes great care in all other aspects of the sport, including the equipment he uses and its maintenance, his understanding of the food sources of fish, his use of proper techniques and their refinements. Because the fly fisherman’s involvement in his sport is so complete, it is probably fair to say that casting a fly as a means of catching fish is probably performed with greater attention to detail than any other method. And this consciousness naturally extends to matters of stream etiquette, which, in essence, is based pretty much on the good old Golden Rule: To wit, if we observe certain standards of respect and even deference toward our fellow fishermen, then perhaps we will have a right to expect the same from them.

Although not carved in granite, there are a few rules to which we must adhere while sharing the stream (and lake, and saltwater) environment with other people.

Countless stories are told about the rudeness of our fellow fishermen. For the most part, this coarse behavior is not intentional; rather it comes from not understanding the etiquette the sport requires. For some fly fishermen, educating these impertinent souls just isn’t their style; but I believe, if we refrain from doing so, the problem of not respecting other people’s fishing will remain.

As a general rule all fishermen should be given enough room to carry out their angling as the conditions and location require. Every person has his individual preferences. In the West there are some who like total seclusion and will leave the stream if they see another fisherman. Still others like companionship and camaraderie, also a part of the sport. Not knowing which type you are confronting, you’re well advised to avoid crowding and give the other fisherman adequate space to enjoy his sport.

I once had an experience in which a companion and I had selected a spot containing a few very large fish that we knew would be working during a particular evening hatch. Upon our arrival we found ourselves alone, but after a few minutes another angler appeared, obviously upset that we had taken his spot. Slowly, as the hatch progressed, he made his way, inch by inch, step by step, closer to the rising fish that we were working. Finally, in disgust, I stopped and asked him if he would like to take my location, since he was standing virtually on top of me anyway. To make matters worse, he happened to be an acquaintance and an angler who should have known better. The hard truth is, no matter how many times you have fished a stream or a certain pool, you do not own the river, the location, or the fish. Whoever is there first gets to fish it. Respect that right.

Anglers always try to reach the best pool first, before it has been fished by others. But, unfortunately, there will be times when another fisherman occupies your spot when you arrive. The proper thing to do is to wait until your predecessor has completed his stay before even thinking of stepping into the water. Even when the other person appears to have finished up, it is a good idea to ask whether he has completed his fishing before wetting your line. Since he was there first, you must respect his right to fish the pool at his own speed and leisure, regardless of your schedule.

Fly fishing has its contemplative moments, which usually involve sitting on the bank, waiting, and watching, rather than actually fishing. When you encounter such a scene, you must always ask the other angler his intentions before setting foot in the water. There is nothing more annoying than when, after you’ve decided to rest a fish or a run, someone else comes along and starts fishing it. If you respect the other person’s reasons for waiting, you will gain a friend.

There is always a question as to who has the right of way when one fisherman is fishing upstream and another is fishing down. Although upstream fishing is prevalent, wet fly and streamer fishing traditionally requires a downstream method. But because greater water disturbance is generated by the downstream angler, and because the upstream working fisherman has greater wading problems, the upstream working angler has the right of way over someone who is fishing down. The downstream fisherman should retire from the river or walk around the other angler, avoiding the undue disturbance that his technique often brings.

Wading through a run where another fisherman intends to fish or is already fishing is another common mistake. While fishing the famous Green Drake hatch on the Henry’s Fork in Idaho with a fellow guide and store owner, Mike Lawson of Henry’s Fork Anglers, I experienced a classic example of this problem. Upon arriving at the water, we saw other fishermen scattered about, fishing to the selective rises. Now, the Henry’s Fork is a wide, but wadable river, and can nicely accommodate a great number of fishermen. We entered the water, and found our own fish to work, but, typical of the Henry’s Fork, we also found ourselves near other fishermen. Suddenly, on the bank, a car came roaring to a halt. A person jumped out, scanned the water, quickly donned waders and vest, entered the water, and proceeded to walk right through, not only my fish, but everyone else’s as well, putting them all down. Frustrated and a bit amazed, I asked the fisherman what in the hell he was doing. As he kept plowing through the water he turned and said, “Well, I need to get to the other side.” If he really needed to do that he should have gone upstream or downstream to cross, avoiding other fishermen. Do not wade through an area where fishing is taking place.

Unfortunately, the paths near most streams parallel the bank. Fishermen love to watch the water for any working fish that might be present. Because the banks themselves are often higher than the stream, observation is easy, not just for the angler, but—you guessed it—for the trout, too. If a fisherman happens to be working a run or working a bank you are walking along, give him a wide berth by walking back and around his location. Never allow yourself to become visible to the fish another angler is working, for you will surely spook those fish.

Walking or standing on the bank near where another angler is fishing also shows bad manners. Here, the bankside angler’s high profile will put fish down.

Private water should also be respected by the fly fisherman. Always ask permission for access rather than operating on the assumption that all fish are public and therefore the land surrounding belongs to the public as well. Once you have received permission, be sure to close fences after entering and see that they are secure. Do not litter or disrupt crops or habitats. Respect people’s property as you would hope they would respect yours.

Landing and playing fish also has its set of rules. In most cases, the angler who has hooked a fish has the right of way throughout a stream. If an angler has a running fish and needs to pass through your area, let him do so. Reel up and either step back to the bank or remain stationary and allow him to go around you. Also, never take the responsibility of landing another man’s trout unless you are asked to assist; it can end in disaster. Even if the angler asks for help, give it willingly but proceed with caution: Your mistake could cause great disappointment and frustration to your fellow fisherman.

The above does not cover all the myriad streamside problems that may occur, just the most common ones. The manner in which we conduct ourselves on the various fishing waters is obviously as important as how we fish them. Etiquette, although it does not carry the force of law, or even regulation, is fundamental to the sport of fly fishing. And coupled with our attitude toward the fish and their environment, our manners become perhaps the most important aspect of the sport. The very future and livelihood of our sport depends on each of us and how we act, whatever our level of ability or our method.

Perhaps the greatest challenge facing fishermen, both today and in the future, is preserving the water systems that make the sport possible. Simply stated, if there is not adequate water for fish to thrive, all fishing, fly fishing included, will be impossible. Every fisherman must, therefore, concern himself with the precious environment in which fish are born, survive, and perpetuate themselves.

Up until the 1970s, the word “conservation” had only a dictionary meaning for most of us. Often, the manipulation of natural resources was governed by complacency and greed. Each bred an attitude that, in effect, said if one water resource became non-productive there would always be others to take its place. Well, I’m saddened to report that we are slowly running out of fishable systems. If we are not careful we will destroy what is left.

Industry has undeniably brought great wealth to individuals and to the nation. But, sadly, in too many instances, it has degraded most waterways it has touched. Streams that flowed through industrialized areas were often regarded either as highways, or as repositories for waste—everything from toxic chemicals to sewage—that affects not only the fish but the entire aquatic ecology. Poor forestry practices, particularly clearcutting, have caused erosion, clogging our streams and creeks with silt that renders them totally unsuitable for spawning or fish life.

Man has also taken it upon himself to divert the flow of our rivers to his own purposes. Hydroelectric dams, while providing cheap energy to the masses and irrigation to the farmer, have, in many cases, totally eliminated migratory runs of salmon and steelhead that existed in abundance just a few decades ago. Little thought was given to fish when the dam-building craze was at its height. Inadequate or nonexistent fish ladders were the norm, and nitrogen supersaturation at the base of the spillways, caused by the plunging water, was never anticipated. Granted, some dams have also provided fabulous tail race trout fisheries below the dams, but for the most part, dams have brought more harm than good. Only in recent years have the problems caused by dams been addressed, and largely through the efforts of fishermen will future runs of migratory fish survive.

It was once thought that the reservoirs created by dams would provide an endless supply of recreational resources, but they quickly developed into storage facilities for silt or toxic wastes, altering the complete ecology of the water. Yes, there was and is fishing in these impoundments, but biologists today concede that it is only a matter of time before many become useless for fish and recreational fishing.

Diverting rivers causes as many problems as harnessing their energy. It seems that every lover of the outdoors wants his little cabin in the woods beside a stream, but he does not want that friendly little river to turn on him and flood. To protect his property and investment, he “rip-raps”—channels the course of the river away from his private domain. This seemingly sensible precaution robs the fish of vital habitats. What was once a meandering river system, providing adequate habitat and holding water for fish, quickly turns into a velocity shoot, transferring water from Point A to Point B as quickly as possible. Little is left in these stretches for the fish to survive in.

Some of these intolerable conditions and hardships perpetrated by man on fish were done with high purpose and nothing but the best of intentions—except they backfired. Through ignorance, for many years fishermen, as well as various fish and game management personnel, felt that wild fish populations, once depleted, could easily and simply be replaced through massive introductions of hatchery-raised species. At the turn of the century, fish culturists distributed various species that did help populate river systems with good variety. But after World War II, when fishing popularity increased and wild fish populations rapidly diminished, sportsmen clamored for more fish. Planting was thought to be the solution to the problem. Unfortunately, many of the same well-intentioned officials who were responsible for the ambitious planting programs have recently discovered how destructive hatchery-raised fish can be to the productivity of the river systems.

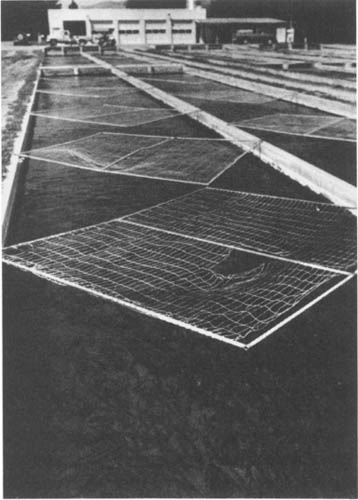

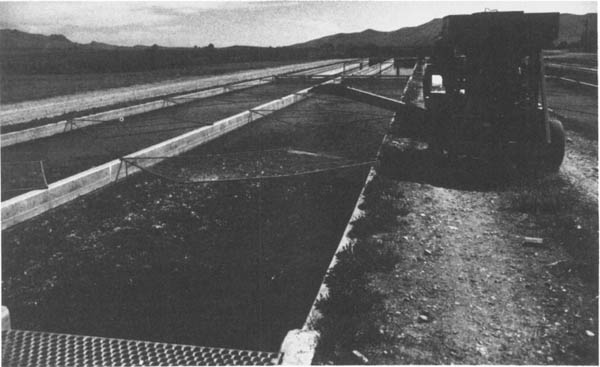

Hatchery fish are raised in great quantities and in a congested environment unlike that of natural streams.

Hand-fed through most of their lives, hatchery fish tend to have difficulty adapting to natural feeding. Consequently, when introduced to streams, many die within a short period of time.

In one very important Montana Fish and Game study, conducted on the Madison River in the early 70s, the truth about supplementation came to light. First, hatchery fish were seen to have a very high mortality rate when introduced into the natural environment. Because they had been hand-fed in the hatchery to a catchable size, many simply were not able to adapt to the competitive wild environment. Also, it was discovered that when hatchery fish were introduced in great numbers to a particular river location, they tended to drive out the otherwise territorial resident wild trout. The overall effect was that the planted fish died, the wild fish disappeared, and a small fish population remained in the river. What little population remained to spawn turned out to be a breed greatly inferior to those that had originally existed.

Fishery management people also dabbled in the genetic structure of trout, looking for a fish capable of maturing very rapidly, obtaining a uniform size, and even spawning at different times of the year for easier management within the concrete raceways of the hatcheries. The result was a genetically inferior species that, although easily reared, no longer attained uniform growth but took on a girthless, snakelike profile.

Again, creating problems of these kinds was not the intention of those involved. In their enthusiasm for enhancing our fisheries, few foresaw the end results. Certainly, in the early stages of fishery experimentation, there was no way of knowing that crossing various genetic strains of fish would produce weaklings. But now there is a scientific basis for understanding these phenomena and many state programs are moving to rectify the situation, by reducing hatchery planting and watching more closely the genetic structure of the fish.

In all fairness to hatchery programs, it should be noted that, although they can have serious negative side effects in a wild trout fishery, there are waterways and impoundments that would be completely devoid of fish were it not for these programs. Lake systems that freeze solid during the winter, become excessively warm in summer, or have a limited capacity to perpetuate fish populations need to be planted. Also, because most states have different water types, containing varying degrees of temperature ranges, were it not for introduction programs, a full array of both cold and warm water species would not exist.

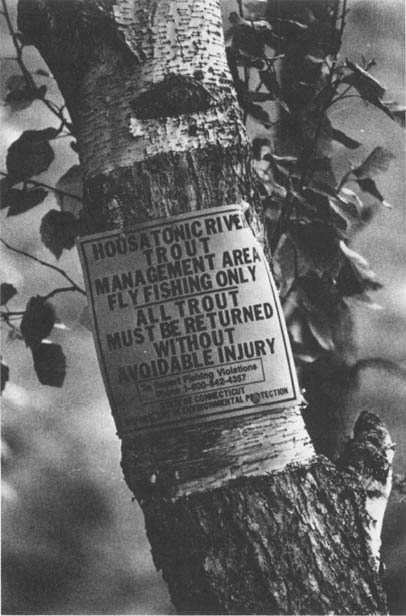

A necessary sign of the times.

Hatcheries do have their place, but for the fly fisherman of today and the future it is obvious that some type of catch-and-release or restricted kill regulations, accompanied by more enlightened attitudes, is vitally necessary if we are to have fish of any consequence in years to come.

It is a fact that we are not living in an era that existed 50 or 100 years ago. Today, because of excessive fishing pressure, we can no longer live with the idea that we are entitled to an unlimited supply of fish. As my good friend Jack Hemingway stated and is often quoted, “It is not the responsibility of state fish and game commissions and agencies to supply protein to the fishing public.” We know that the fish and game departments have tried to rectify a bad situation by supplementation, but we also know now that those efforts, however well intentioned, are detrimental to the water systems in the long run. More and more states are beginning to recognize that catch-and-release regulations have positive effects on both the fisheries and the fishermen. Today, those areas with highly restrictive regulations often produce not only substantial quantities of fish, but large, quality individuals as well. Fishermen quickly see the difference and gravitate to these areas, recognizing that where fish are plentiful and smart, there is more sport and more pleasure. Your consideration is also needed.

Even with catch-and-release regulations to guide us, the fish are still threatened unless we pay close attention to the manner in which we handle and release them. Most fish, especially trout, are fragile and cannot withstand excessive abuse at the hands of a fisherman. The slightest loss of blood or mild overexertion from overplaying can be lethal. Therefore, when hooking, playing, landing, and releasing fish, we must take care to minimize any damage. Barbless hooks are always a good idea, since they are easily removed without tearing the jaw or drawing blood. Also, instead of shotputting a fish back to the water, it is very important to hold it for a few moments facing upstream and move it back and forth, allowing it to get needed oxygen back into its bloodstream, and thus ensuring its survival.

How we regard and handle the environment in which fish live is our biggest challenge for the future. You may live in an area that is relatively free of environmental problems, but don’t be complacent. What becomes deplorable in one part of the country can, and will, reach you as well. Regardless of where and how problems exist, we must all get involved if we are to save the life-giving water and fish habitat that we presently have. It cannot be the other person’s fight. If we are to have fishing for our children and our children’s children, we must all take a stand against those practices, organizations, and people that bring destruction to our water systems. It is simply up to all of us.

Simple fly-tying equipment allows you to create your own imitations of the foods that fish feed upon.