Why people pursue fly fishing rather than other fishing methods has probably been the most debated question concerning the sport. There is no definitive answer to this question. One person’s attraction may not be another’s, but certain common bonds—a love of the outdoors, a passion for understanding various species, and a patience born of deep feeling for the beautiful complexity of the sport—unite all fly fishermen.

Under my father’s tutelage I began as an angler when I was six. I have fished the fly every season since, and my love for it continues to grow unabated. I can’t seem to get enough of fly fishing, and when the season for it ends in Sun Valley, where I live, I find myself packing my gear to fish the fly in other parts of the world. What is it about the sport that draws us so completely to it?

Essentially, fishing as a pastime is a game, and the sport of fly fishing is its pinnacle. In all games we have an opponent and in the sport of fishing the opponent becomes the fish itself. Because this incredible adversary neither lies nor cheats but rather reacts upon its own instincts for survival, the intrigue of angling for it on equally honest terms runs deep.

For most people, the fishing game starts at an early age, simplified in form and technique. A fishing pole, a plain line, a pocket full of hooks and sinkers, and a coffee can filled with night crawlers or grasshoppers generally starts the game in motion. But after awhile, something begins to happen. Through observation of fish habits and, perhaps, an inherent desire to make the game more complex, the angler slowly turns his attention toward the fly rod and the insects so attractive to the fish. By becoming a fly fisherman, the angler discovers he has entered a world and a game that can consume him for the rest of his life. Dealing as it does with Nature and her creatures, the sport of fly fishing is always variable, never constant, and the angler alert to its variations learns something new on every outing. Indeed, the daily subtle changes that the angler faces are one reason why the appeal of fly fishing is so great for so many people.

The knowledge gained through fly fishing holds special appeal, too. A good fly fisherman finds himself becoming an amateur ichthyologist studying fish, a hydrologist analyzing water, an entomologist identifying insects, and a meteorologist recognizing weather patterns. All these subjects require a lifetime of attention and study, but the quest for knowledge is one of the sport’s continuing attractions.

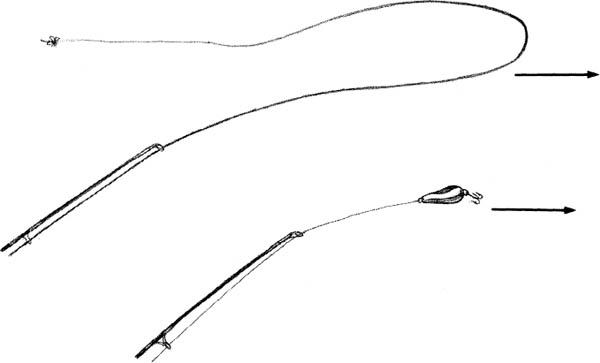

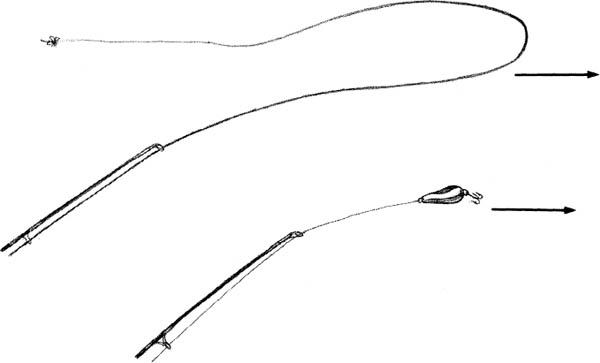

Fly fishing has often been described as an art form. In other methods of fishing, the weight of lure, plug, or bait propels the cast. In fly fishing, the motion of the rod casts the fly line and the line, in turn, the fly. Placing the fly exactly where it should go requires precision and skill—and more delicacy and “touch” than does any other casting method. In fly fishing, as we shall see, the presentation of the fly—that is, the manner in which it is laid on the water and made to act—is at least as important as the choice of the fly. The “chuck and chance” technique so often characteristic of other casting methods won’t work for the fly fisherman. He must put in the hours to perfect both his casting and his presentation techniques.

In other fishing methods (lower illustration), the weight of the lure, plug, or bait propels the cast. In fly fishing (upper illustration), the motion of the rod casts the fly line, which, in turn, casts the fly.

Most fly fishermen ultimately become more interested in the method than in the final outcome of fishing the fly. They rapidly acquire a quiet admiration for the fish they hunt, and they come to realize that to kill it is to kill the very thing that keeps them coming back to the water. It becomes more important that the fish survive to be hooked again—and again—for it is in the hunting, stalking, and deceiving that the satisfaction lies, not in the keeping and killing.

Fly fishing is not an especially “physical” sport. All it really requires is a desire to learn. Because it actually sparks that desire, fly fishing’s appeal is broad, and women and children of all ages can and do become equal participants with men, and sometimes even prove to be the better anglers.

Fly fishing is an endlessly aesthetic sport. Roderick Haig-Brown neatly summed up its appeal for any angler, young or old, male or female, in his book A River Never Sleeps: “I still don’t know why I fish or why other men fish except that we like it and it makes us think and feel. But I do know that if it were not for the strong, quick life of rivers, for their sparkle in the sunshine, for the cold greyness of them under the rain and the feel of them about my legs as I set my feet hard down on rocks or sand or gravel, I should fish less often. A river is never quite silent, it can never of its very nature be quite silent. It is never quite the same from one day to the next. It has its own life and its own beauty and the creatures it nourishes are alive and beautiful also. Perhaps fishing is for me only an excuse to be near rivers. If so I’m glad I thought of it.”

This book has been written not only for novice or entry-level fly fishermen but also for those fishermen who have attained, or wish to attain, an intermediate’s grasp of the sport. It is not a book on advanced technique, theories, and application, but rather a book that specifically deals with detailed and pertinent information that should be known by any fly fisherman. In addition to the basic information, such as fly casting, entomology, and various fly fishing techniques, I will touch upon the use of the fly rod for such fish as bass, steelhead, and salmon, as well as saltwater species.

In fly fishing, as in any other sport, misconceptions abound, and this book is intended in part to clear up some of them.

More than anything, this book is a primer on fly fishing. If reading it stimulates you to learn even more about the sport, then it will have accomplished its purpose.

—Bill Mason

Sun Valley, Idaho

Frontispiece to the original edition of The Boke of St. Albans (1496). The section in the book titled “Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle,” attributed to Dame Juliana Berners, is widely considered the first how-to text on fly fishing.