XXV

HIGH on the slope above the pond, and walled in with June grass, the corn-patch of the farm garden has been lying unplanted while waiting for warmer weather. We are so far to the north and so liable here to late frosts that early planting is a risk with such things as corn, though we plant as early as we can, well knowing that late planting brings another risk when the cold of autumn comes in a night across the hills. This year we have had rather a cold early summer, and these cold June nights have seen frosts in the lowlands of the farms. This morning, however, a change came, the sun rising hot and living over an earth already warmed with a south wind which had risen in the night.

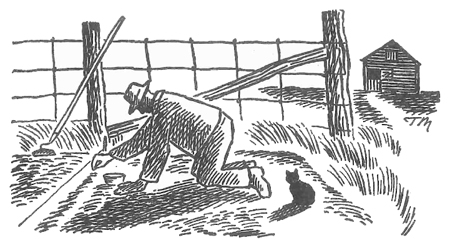

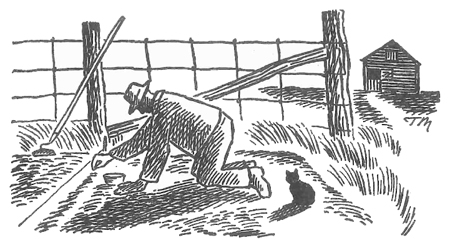

In this northern world, a good planting day is almost a ritual accord with Nature, so much depends on it and so little time have we to lose. All up and down the farm land, we all of us went early to our work, and from my own field I could see Irving and his horses rhythmically harrowing an acre just too far away for me to hear his voice stopping and urging on his team as they walked parallel to the blue waters of the pond. Our neighbors to the south, meanwhile, had gone down to their already half-planted garden, active and busy figures working with the earth in the welcome heat and splendor of the day.

Lawrence having come to give me a hand, we got in our summer corn, both of us gratefully busy not with death but with life. Lawrence has been home about a year from the wars. He is in his later twenties, a young man of middle height and very powerfully built, and we like to have him work with us not only for his good temper but also for that serene, almost placid, quality which so often accompanies great physical strength. He has blue eyes, white teeth, and a great shock of yellow hair which, because he wears no hat, the sun burns to a kind of straw color above the healthy tan of his face.

Lawrence has long been a friend of the farm, having lived with us here in the old days, and shared the summer and the winter work and the autumn evenings by the open fire.

Working in the corn patch, the sun seemed to stand still in a sort of agricultural high noon. The earth was not hot, but warm to the touch like the side of a living animal, and growing warmer every hour as it lay basking in the sun. So warm, so radiant was the sun that there seemed no shadows on the patch in the glare of fruitful light, though in a corner the brown-paper bags of fertilizer stood hunched with a lump of shade to one side.

On the new telephone wires, a single barn swallow sat for a long while, living in his own world, and well aware of ours. We planted in rows, dropping the seed in careful spacing, Lawrence carrying an aluminum dipper he fancies and I a small lard pail which does duty every year. The patch had already been manured, a great load of old, well-seasoned barn manure having been worked in and harrowed under; dried clots and lumps of it lay dusty underfoot. One could smell the hot earth and the life within it and the sun.

Pale-yellow, wrinkled, horny, and shrunken, the corn lay in the furrows, sown on earth we had scuffed over a sprinkling of commercial. There it would awaken and rise up as corn, the truly sacred plant of America, the staff and symbol of its ancient being. The long rains would come from the east and the sea, and the black thundershowers from the west, and time and the earth would create a new thing, and the green and rustling sound of corn would be heard on the August wind.

When we had finished, we both of us washed in the shed, gratefully sluicing and soaping off field dust, sweat, and the clinging smell of fertilizer, and holding our heads beneath the plentiful warm water pouring from a tap. I had no blisters to study for it is long since I have blistered easily.

When we felt comfortable and clean, and had changed clothes in the shed chambers, we went together into the big kitchen where Elizabeth was waiting, into the pleasant room with its afternoon “sunlight, its domestic order, and its sense of peace.

FARM DIARY

Have been planting some hills of “Butternut” squash, an excellent vegetable one can use from late summer on into early winter. For summer use, I like the Italian summer squash or vegetable marrow called the “Cocozelle” because it grows quickly, cooks promptly, and makes many a pleasant dish. The old-fashioned “summer squash” has never been so good since the government straightened its neck. / The farm bell having rusted up over the winter, Lawrence has taken it down to the village to be sanded and re-gilded. / Our friend Bee Day—Mrs. Maurice Day—presents us with a share of wonderful clam chowder just off the stove, and we warm it up at home, drop in the “Boston crackers” and finish it to the last potato slice and the last sublime clam.

* * *

In summer, the menfolk of our state make the best of the warm months and do the field work stripped to the waist. Long before the late, shirtless war was upon us, it was almost a state custom to work thus rigged, and one looked from the road out on what might have been an agricultural community of Fenimore Cooper Indians in blue denim pants. In our climate the fashion seems to me an excellent one, though it is perhaps not one to be followed in regions of fiercer heat and light.

The scene thus set is vigorous and alive, and there is a classical rightness to it. It is far removed from the idiot world of vitamin pills. The field and the workers are one; they form an earthly unity, and share together the weight of the sun and the brushing by of the wind. Our abstract civilization is all the poorer for having lost its sense of living by the body as well as by the brain and nerves. When it deals with the flesh, it vulgarizes it, having no sense whatever of its meaning. Perhaps it is well to remember once in a while that we were made in a human completeness of bone and sinew, and given the earth for our inheritance and good cheer.