CHAPTER THREE

Let’s Look at the Rules

The more constraints one imposes, the more one frees one’s self. And the arbitrariness of the constraint serves only to obtain precision of execution.

—Igor Stravinsky

There are rules in sports. Three strikes and you’re out. You have to make ten yards in four downs to get another first down. You can’t touch the soccer ball with your hands. Rules are a great annoyance to the beginner, but to the experienced player, they make for a beautiful game.

Baseball is a confusing game for most non-Americans. There are so many rules and subtleties. I confess to not understanding the rules in soccer, although I am getting better. And forget about understanding hockey.

There are rules in economics, but many are not as well-known. And breaking these rules has consequences for individuals, companies, and countries. Sadly, there is no independent referee who can blow a whistle and stop the game, assess a penalty, and make you obey the rules. There is, however, a market that can decide not to buy your currency or your bonds if you don’t play by the rules.

We are going to look at some of the more important rules in this chapter. But, gentle reader, don’t panic. These rules are fairly easy to understand if we take out the academic jargon often associated with them. And if you get it, then it is much easier to understand the consequences of what happens when a nation violates the rules, both from a policy perspective and from a personal investing point of view.

Also sadly, there is not necessarily an immediate penalty for a violation. As we saw in the last chapter, a country can rock along for a very long time before that Bang! comes along and the flag finally gets thrown. But in the fullness of time, if a country does not correct its misbehavior, the end will be full of weeping and wailing and gnashing of teeth. And a lot of finger pointing—it is always the other side’s fault.

Note that the rules are the same for everyone and every country. These are basically accounting rules known as identity equations. They are like E = MC2 or F = MA (force is equal to mass times acceleration). They are just true. If they are not, then a thousand years of accounting is wrong. You may not like what they say or not like the consequences, but you have to deal with the real world, take it or leave it.

For instance, in 1976, as a very young entrepreneur (no one would hire me, so I had to work for myself), I had launched my first business, and my best friend did my taxes. I thought I had sent the IRS more than enough to cover me. Then he came to me with a tax bill that was more money than I had ever seen in one place. I guess the concept that I had to pay the employer’s side of Social Security had escaped my attention in my quest to simply survive, along with all sorts of alternative minimum taxes and other things I had never heard of. Reality can be a real bitch.

The importance of knowing the rules was forcefully driven home. And the rules we will now look at are every bit as important as knowing those tax laws. Even if you don’t know about them, they exist and will eventually come to haunt you (whether you’re an individual, a company, or a nation) if you ignore them.

The Federal Reserve and central banks in general are currently attempting a major and highly experimental operation on the economic body, without benefit of anesthesia. They are testing the theories of four dead white guys: Irving Fisher (representing the classical economists), John Keynes (the Keynesian school), Ludwig von Mises (the Austrian school), and Milton Friedman (the monetarist school). For the most part, the central bankers are Keynesian, with a dollop of monetarist thrown in here and there. They have every intention of using their liquidity tool to try to prevent deflation, spur the economy and encourage us to borrow and spend more. We’ll talk about how likely that is to work later.

Alice laughed. “There’s no use trying,” she said, “one can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t had much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

—From Through the Looking Glass, by Lewis Carroll

Economists and policy makers seem to want to believe impossible things in regard to the debt crisis currently percolating throughout the world. And believing in them, they are adopting policies that could well lead to tragedy.

Let’s look at the basic equation that summarizes a nation’s gross domestic product:

Which is to say, the gross domestic product of a country is equal to its total consumption (personal and business) plus investments plus government spending plus net exports. Again, this equation is known as an identity equation: It is true for all countries and times. And it is rather simple in concept but has profound implications.

Let’s examine some of those implications. First, what happens if the C drops? That means that, absent something happening elsewhere in the equation, GDP is going to drop. That circumstance is typically called a recession.

Keynesian economists argue that the correct policy response is to boost the G through fiscal stimulus, allowing consumers and businesses time to adjust and recover, and to gradually remove that stimulus as the economy returns to its normal growth trajectory. And as an added measure, it helps if the central bank will become more accommodative, with lower interest rates and an easy-money policy to give further stimulus to business and consumers. In most places and in most times in recent (as in 60) years, these policies have worked to help bring an economy through a recession.

There are, however, those who argue that such a policy also keeps in place the imbalances that cause the problems (such as ever-increasing growth in consumer borrowing and housing bubbles), and we’ll return to that argument later in the book, but for now let’s acknowledge that a boost in G provides a temporary boost in GDP. Elsewhere, we will show that the boost is indeed temporary, but few will argue that it does not make a short-term difference. We believe that the recent stimulus in the United States, as an example, did in fact have a temporary effect and kept the United States out of what might have been a depression, but not without its own costs. That debt must be repaid.1

Again, the idea is to try to offset the effects of a retrenching consumer and business sector and give the overall economy time to recover. The United States began to withdraw from the stimulus in the summer of 2010. And sure enough, the economy is slowing down. Only time will tell whether the economy is strong enough to return to a sustainable growth trajectory.

The hope is that with the stimulus you can give a jump-start to consumer final demand. In macroeconomics, aggregate demand is the total demand for final goods and services in the economy at a given time and price level. It is the amount of goods and services in the economy that will be purchased at all possible price levels. This is the demand for the gross domestic product (GDP) of a country when inventory levels are static.

Remember that for most developed economies consumer spending is the biggest part of the economy. In a recession, typically one or more parts of the economy, such as consumer spending and investment, retreat; therefore, the objective of stimulus is to get demand back on track. For economic theories that see final demand as the driving force behind growth, recessions are simply a problem of a lack of some part of our equation like consumer spending and/or investment. Get those back in gear, and the economy moves forward.

Now, in fairness to Keynes, he also asserted that governments should run surpluses in good times, something that most countries have not seemed to be able to do. In our view, one of the main faults of the Bush administration, in conjunction with a profligate Republican Congress, was that they squandered the surpluses that we now need. We will deal with Vice President Cheney’s assertion that “deficits don’t matter” in due course.

Before we go into the other, more profound implications of our equation, let’s visit a few other topics that will give us needed insight into understanding the dynamics of our current economic quandary.

There are two, and only two, ways that you can grow your economy. You can either increase your (working-age) population or increase your productivity. That’s it. There is no magic fairy dust you can sprinkle on an economy to make it grow. To increase GDP, you actually have to produce something. That’s why it’s called gross domestic product.

The Greek letter delta (Δ) is the symbol for change. So if you want to change your GDP you write that as:

That is, the change in GDP is equal to the change in population plus the change in productivity. Therefore—and I’m oversimplifying a bit here—a recession is basically a decrease in production (as normally, populations don’t decrease).

There is one clear implication: If you want your economy to grow, you must have an economic environment that is friendly to increasing productivity.

While government can invest in industries in ways that are productive, empirical evidence and the preponderance of academic studies suggest that private companies are better at increasing productivity and producing long-term job growth.

Going to the United States for a second, studies show that business start-ups have produced nearly all the net new jobs over the last 20 years. Let’s look at this analysis by Vivek Wadhwa.

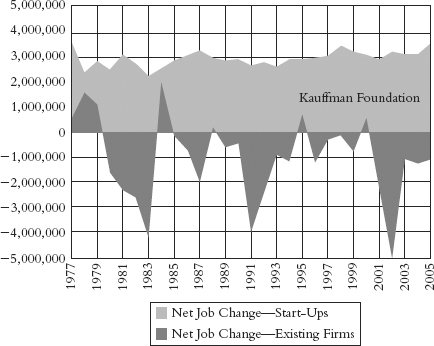

The Kauffman Foundation has done extensive research on job creation. Kauffman Senior Fellow Tim Kane analyzed a new data set from the U.S. government, called Business Dynamics Statistics, which provides details about the age and employment of businesses started in the U.S. since 1977. What this showed was that startups aren’t just an important contributor to job growth: they’re the only thing. [Figure 3.1] shows that most net jobs in the US were created by startups. Without startups, there would be no net job growth in the U.S. economy. From 1977 to 2005, existing companies were net job destroyers, losing 1 million net jobs per year. In contrast, new businesses in their first year added an average of 3 million jobs annually as [Figure 3.1] shows.

Figure 3.1 Start-Ups Create Most New Net Jobs in the United States

Source: © 2010 Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

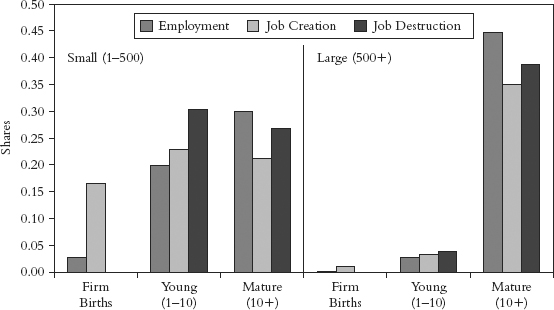

When analyzed by company age, the data are even more startling. Gross job creation at startups averaged more than 3 million jobs per year during 1992–2005, four times as high as any other yearly age group. [See Figure 3.2.] Existing firms in all year groups have gross job losses that are larger than gross job gains.

Figure 3.2 Job Creation and Loss by Firm Age (average per year, by year-group, 1992–2005)

Source: © 2010 Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

Half of the startups go out of business within five years; but overall they are still the ones that lead the charge in employment creation. Kauffman Foundation analyzed the average employment of all firms as they age from year zero (birth) to year five. When a given cohort of startups reaches age five, its employment level is 80 percent of what it was when it began. In 2000, for example, startups created 3,099,639 jobs. By 2005, the surviving firms had a total employment of 2,412,410, or about 78 percent of the number of jobs that existed when these firms were born.

So we can’t count on the Intels or Microsofts to create employment: we need the entrepreneurs.1

This concept is borne out and enhanced by another study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, “Who Creates Jobs? Small vs. Large vs. Young?” by John C. Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda.2

While there are certainly large firms that are adding jobs (Google, Apple, etc.), on average large firms (500-plus workers) are net destroyers of jobs. Figure 3.3 makes clear that it is start-ups that add the jobs that drive employment. We commend the study to you.

Figure 3.3 Shares of Employment, Job Creation, and Destruction by Broad Firm Size and Age Classes (annual average rates 1992–2005)

Source: National Bureau of Economic Research, “Who Creates Jobs? Small vs. Large vs. Young?” by John C. Haltiwanger, Ron S. Jarmin, and Javier Miranda.

Run through the data from around the world. Where have the vast majority of long-term net new jobs come from, even in China? The private sector. And what is the mother’s milk of the private sector? Money. Investments. Angel investors. Private banking. Private offerings. Public offerings. Loans. Personal savings. Money from friends and family. Borrowing against houses. Credit cards. And anything else that provides capital to business.2

Want to increase productivity and jobs? The best way, it seems, is to encourage private business, especially start-ups.

Now let’s go back to our first equation. You remember,

We will spare you the mathematical rigmarole, but if you play with this equation some, you come up with the following:

That is, the savings of consumers and business equal that which is available to business investment, which in turn helps to grow the economy. But there is a rather large but.

Those savings are also what finances government debt. Unless a central bank elects to print money, government debt must be financed by the private sector. That means, if the fiscal deficit is too large, it will crowd out private investment. But as we have seen, private investment is what fuels productivity growth, so if you don’t have enough savings to satisfy private investment needs, you are choking off productivity growth and the creation of new jobs.

Japan is an instructive example. The government debt-to-GDP ratio has risen from 51 percent in 1990 to over 220 percent by the end of 2011, absorbing almost all of the rather enormous savings of the Japanese public. And what have they gotten for their largesse? Nominal GDP is where it was 17 years ago, and there have been no net new jobs for two decades. Think about that for a moment. In 1990, many pundits were proclaiming that Japan would overcome the United States in the near future. Now they have suffered two lost decades and are on their way to a third as government debt has absorbed whatever capital would have been available to private investment. (See our analysis of Japan further on.)

If you are a country facing a population decline (like Japan), to keep your GDP growing, you have to increase your productivity even more. That is why we have so much to say about demographics later in the book. Population growth (or the lack thereof) is very important. Russia is facing a very serious problem over the next 20 years that will require either a significant increase in productivity or large immigration to stave off a collapsing economy. Russia’s population has declined by almost 7 million in the last 19 years, to 142 million. United Nations estimates are that it may shrink by about a third in the next 40 years. But that’s a story for another book.3

Back to Vice President Cheney’s famous assertion that “deficits don’t matter.” In one narrow sense, he is right. Let’s play a thought game.

Suppose we start a business where the income grows by $100,000 a year every year. Assuming 5 percent interest rates, we could borrow $1 million every year and never really encounter a problem, as our income would be growing at twice the rate of debt service. We are running a deficit as a business (spending more than we make), but the deficit doesn’t matter, since our profits and productivity increase more than the debt service. In 10 years, we owe $10 million, but we are making $1 million and could actually pay down the debt in less than 10 years if we stopped borrowing so much money.

For that business, deficits don’t matter.

But what if interest rates rose to 10 percent and our profits dropped in half? Then, Houston, we have a big problem. Now our profits don’t cover the interest payments. In fact, we have to borrow money just to make the interest payments. As long as friendly bankers cooperate, we can survive. And because we were so profitable for so long, they might just keep lending, assuming that things will get back to normal.

But at some point we need to start showing a profit, or they will stop making those loans and suggest we sell assets or even take them from us.

In that case, deficits matter a whole lot.

It is the same for countries. Governments cannot run deficits in excess of the growth in GDP without eventual consequences. As we will see in the chapter covering the research of Rogoff and Reinhart, things go along well until Bang! bond investors lose confidence in the ability of a government to pay its debt, even if that debt is denominated in a currency the government can print! Bond investors become concerned that the currency will lose its value faster than the interest on the bond will grow. Then interest rates rise, making it even harder for the country to pay back its debt.

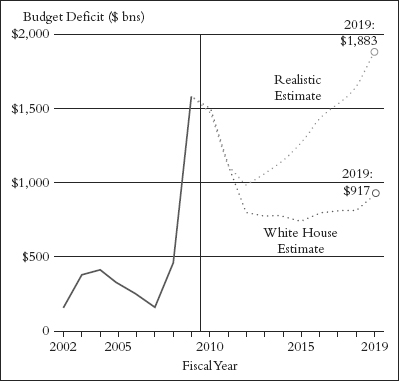

We all know about Greece, but let’s look at the United States. Our fiscal deficit for 2010 is projected to be about 9 percent of nominal GDP (now roughly $14.3 trillion), down from 12 to 13 percent a short while ago. The Congressional Budget Office currently projects that the deficit will still be $1 trillion in 10 years. The Heritage Foundation thinks a more realistic estimate is closer to $2 trillion in just nine years as Figure 3.4 shows. Regardless of the eventual outcome, both numbers are very troubling.

Figure 3.4 Obama Budget Deficit Would Bring Annual Budget Deficits to $2 Trillion

Source: Heritage Foundation. Calculations based on data from the Congressional Budget Office and the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

Dr. Woody Brock has written a very important paper on why a country cannot grow government debt well above nominal GDP without causing severe disruptions to the overall economic system.3

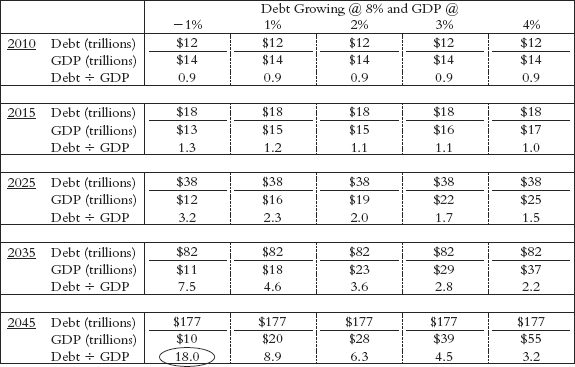

We are going to reproduce just one table from that piece in Table 3.1. Note that this was Brock’s worst-case assumption, adding 8 percent of GDP to the debt each year, and not the 9 to 12 percent we are experiencing today. The Congressional Budget Office long-range projections are growing worse with each estimate, and that assumes a very rosy 3 percent or more growth in the economy for each of the next five years. Under Brock’s scenario, the national debt would rise to $18 trillion by 2015, or well over 100 percent of GDP. Take some time to study the tables, but note that we are going to focus on 2015 and not the outlier years.

Table 3.1 Federal Debt Growth Scenario

Source: Woody Brock.

Brock makes the assumption that U.S. debt will grow about $1.5 trillion a year. That means that by 2015, even assuming an average of 2 percent growth of the economy, the debt-to-GDP ratio would be 110 percent (or 1.1 in Brock’s table).

And in just another 10 years, by 2025, if the deficit were not brought under control, debt-to-GDP would climb to 200 percent. Note that the Heritage Foundation suggests that, under current budgetary law, the deficit will grow by more than the $1.5 trillion a year that Brock projects, in the not too distant future.

The point here is not to predict some future catastrophe but to point out what can happen very quickly if deficits are not brought under control.

It is our contention that long before we ever get to that point (say 2020), the bond market will revolt, interest rates will rise, and the results will be very unpleasant. And that’s for the United States. As we will see later in the book, without some serious intervention, that unpleasant ending could happen to a host of countries in the developed world.

Governments can increase their debt as long as the increase is less than the growth in nominal GDP. It may not be a wise choice to do so, but it does not kill the goose. That is why Cheney argued that deficits don’t matter. The deficit he was commenting on was less than the growth in nominal GDP. We assume that he never thought we (in the United States) would see deficits of 12 percent (worse in some countries). But he should have.

Deficits matter because in good times it is helpful to run surpluses and pay down the debt so that there is room for a policy response in bad times. Running deficits all the time limits their use when you may need them most, as many countries are finding out. There are limits to what even the largest and most powerful nations can borrow. Those limits may seem a long way off, but they are there. And as we will see, there is no magic number that says the end is near. There is no way to determine when the crisis comes.

As the highly acclaimed work of Professors Rogoff and Reinhart (to which we later devote a whole chapter) shows:

Highly indebted governments, banks, or corporations can seem to be merrily rolling along for an extended period, when bang!—confidence collapses, lenders disappear, and a crisis hits. (This is going to be a constant theme throughout the book. It is critical to understand the precarious nature of the bond markets!)4

Voters around the world are increasingly worried that governments are not only taxing the goose that lays the golden eggs but also risking the very life of the goose. And unchecked deficits do in fact risk the economic life of a country. You can get away with them for a while, but at some point you have to deal with them or risk becoming Greece. Or Argentina.

Let’s look at another serious implication, again using the United States as our example.

A $1.5 trillion yearly increase in the national debt means that someone has to invest that much in Treasury bonds. Let’s look at where the $1.5 trillion might come from. Let’s assume that all of our trade deficit comes back to the United States and is invested in U.S. government bonds. That could be as much as $500 billion, although over time that number has been falling. That still leaves $1 trillion that needs to be found to be invested in U.S. government debt (forget about the financing needs for business and consumer loans and mortgages).

A trillion dollars is roughly 7 percent of total U.S. GDP. That is a staggering amount of money to find each and every year. And again, that assumes that foreigners continue to put 100 percent of their fresh reserves into dollar-denominated assets. That is not a safe assumption, given the recent news stories about how governments are thinking about creating an alternative to the dollar as a reserve currency. (And if we were watching the United States run $1.5 trillion deficits, with no realistic plans to cut back, we would be having private talks, too.)

There are only three sources for the needed funds: an increase in taxes, increased savings put into government bonds, or the Fed monetizing the debt, or some combination of all three.

Leaving aside the monetization of debt (for a later chapter on inflation), using taxes or savings to handle a large fiscal deficit reduces the amount of money available to private investment and therefore curtails the creation of new businesses and limits much-needed increases in productivity. That is the goose we will kill if we don’t deal with our deficit.

But It’s More Than the Deficit

We talked earlier about how increasing government debt crowds out the necessary savings for private investment, which is the real factor in increasing productivity. But there is another part of that equation: the percentage of government spending in relationship to the overall economy. Let’s look at some recent analysis by Charles Gave of GaveKal Research.

It seems that bigger government leads to slower growth. Figure 3.5 demonstrates the current situation in France, but the general principle holds across countries. It shows the ratio of the private sector to the public sector and relates it to growth. The correlation is high.

That is not to say that the best environment for growth is a 0 percent government. There is clearly a role for government, but there is a cost to the government sector that takes money away from the productive private sector. Not all private investment is productive, however—for example, housing in the 2000s!

Gave next shows us the ratio of the public sector to the private sector when compared with unemployment (again in France). While there are clearly some periods when there are clear divergences (and those would be even clearer in a U.S. chart), there is clear correlation over time.

And that makes sense with our argument that it is the private sector that increases productivity. Government transfer payments do not. You need a vibrant private sector and small businesses to really see growth in jobs.

At some point, government spending becomes an anchor on the economy. In an environment where assets (stocks and housing) have shrunk over the last decade and consumers in the United States and elsewhere are increasing their savings and reducing debt as retirement looms for a large swath of the aging baby boom generation, the current policies of stimulus make less and less sense. As Gave argues:

This is the law of unintended consequences at work: if an individual receives US$100 from the government, and at the same time the value of his portfolio/house falls by US$500, what is the individual likely to do? Spend the US$100 or save it to compensate for the capital loss he has just had to endure and perhaps reduce his consumption even further?

The only way that one can expect Keynesian policies to break the “paradox of thrift” is to make the bet that people are foolish, and that they will disregard the deterioration in their balance sheets and simply look at the improvements in their income statements.

This seems unlikely. Worse yet, even if individuals are foolish enough to disregard their balance sheets, banks surely won’t; policies that push asset prices lower are bound to lead to further contractions in bank lending. This is why “stimulating consumption” in the middle of a balance sheet recession (as Japan has tried to do for two decades) is worse than useless, it is detrimental to a recovery.

With fragile balance sheets the main issue in most markets today, the last thing OECD governments should want to do is to boost income statement at the expense of balance sheets. This probably explains why, the more the US administration talks about a second stimulus bill, the weaker US retail sales, US housing and the US$ are likely to be. It probably also helps explain why US retail investor confidence today stands at a record low.5

This is the fundamental mistake that so many analysts and economists make about today’s economic landscape. They assume that the recent recession and aftermath are like all past recessions since World War II. A little Keynesian stimulus, and the consumer and business sectors get back on track. But it is a very different environment. It is the end of the debt supercycle. It is Mohamed El-Erian’s new normal.

As we will see in a few chapters, the periods following credit and financial crises are substantially different, play out over years (if not decades), and are structural in nature and not merely cyclical recessions. And the policies needed by the government are different than in other cyclical recessions. We will go into those later in the book, as it differs from country to country. Business as normal is not the medicine we need, but it is what many countries are going to attempt.

Not Everyone Can Run a Surplus

The desire of every country is to somehow grow its way out of the current mess. And indeed that is the time-honored way for a country to heal itself. But let’s look at yet another equation to show why that might not be possible this time. It is yet another case of people wanting to believe six impossible things before breakfast.

Let’s divide a country’s economy into three sections: private, government, and exports. If you play with the variables a little, you find that you get the following equation. Keep in mind this is an accounting identity, not a theory. If it is wrong, then five centuries of double-entry bookkeeping must also be wrong.

By domestic private sector financial balance, we mean the net balance of businesses and consumers. Are they borrowing money or paying down debt? Government fiscal balance is the same: Is the government borrowing or paying down debt? And the current account balance is the trade deficit or surplus.

The implications are simple. The three items have to add up to zero. That means you cannot have both surpluses in the private and government sectors and run a trade deficit. You have to have a trade surplus.

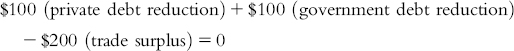

Let’s make this simple. Let’s say that the private sector runs a $100 surplus (they pay down debt), as does the government. Now, we subtract the trade balance. To make the equation come to zero, it means that there must be a $200 trade surplus.

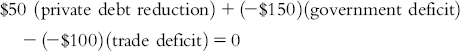

But what if the country wanted to run a $100 trade deficit? Then that means that either private or public debt would have to increase by $100. The numbers have to add up to zero. One way for that to happen would be:

(Remember that we are adding a negative number and subtracting a negative number.)

Bottom line: It is the change in these things that matters, so you have a trade deficit but it must fall if you want to have more private investments. You can run a trade deficit, reduce government debt. and reduce private debt, but not all three at the same time. Choose two. Choose carefully. It is the relative changes in these three items that matter over time.

We are going to quote from a paper done by Rob Parenteau, the editor of The Richebacher Letter, to help us understand why this simple equation is so important. Rob was writing about the problems in Europe, but the principles are the same everywhere.

The question of fiscal sustainability looms large at the moment—not just in the peripheral nations of the eurozone, but also in the UK, the US, and Japan. More restrictive fiscal paths are being proposed in order to avoid rapidly rising government debt to GDP ratios, and the financing challenges they may entail, including the possibility of default for nations without sovereign currencies.

However, most of the analysis and negotiation regarding the appropriate fiscal trajectory from here is occurring in something of a vacuum. The financial balance approach reveals that this way of proceeding may introduce new instabilities. Intended changes to the financial balance of one sector can only be accomplished if the remaining sectors also adjust in a complementary fashion. Pursuing fiscal sustainability along currently proposed lines is likely to increase the odds of destabilizing the private sectors in the eurozone and elsewhere—unless an offsetting increase in current account balances can be accomplished in tandem.

. . . The underlying principle flows from the financial balance approach: the domestic private sector and the government sector cannot both deleverage at the same time unless a trade surplus can be achieved and sustained. Yet the whole world cannot run a trade surplus. More specific to the current predicament, we remain hard pressed to identify which nations or regions of the remainder of the world are prepared to become consistently larger net importers of Europe’s tradable products. Countries currently running large trade surpluses view these as hard won and well deserved gains. They are unlikely to give up global market shares without a fight, especially since they are running export led growth strategies. Then again, it is also said that necessity is the mother of all invention (and desperation, its father?), so perhaps current account deficit nations will find the product innovations or the labor productivity gains that can lead to growing the market for their tradable products. In the meantime, for the sake of the citizens in the peripheral eurozone nations now facing fiscal retrenchment, pray there is life on Mars that exclusively consumes olives, red wine, and Guinness beer.6

This has profound implications for those countries struggling to deal with large government deficits, large trade deficits, and a desire on the part of individuals and businesses to reduce their debt while wanting the government to curtail its spending. Something in that quest has to give.

The time-honored (and preferred) way a country digs itself out from a debt or financial crisis is for a country to grow its way out of the problem. And that is what Martin Wolf, the highly regarded columnist for the Financial Times in London, suggests that Great Britain should do.

Wolf argues (rather cogently) that the answer is to increase exports and for a further weakening of the pound. Quoting:

Weak sterling, far from being the problem, is a big part of the solution. But it will not be enough. Attention must also be paid to nurturing a more dynamic manufacturing sector. With the decline in energy production under way, this is now surely inescapable.7

When Martin Wolf writes, he reflects what the cognoscenti of Britain are thinking. The pound is already down by 25 percent against the dollar as we write. We think it could go down even further. John has long been on public record that the pound could reach parity with the dollar (when the pound was much stronger) and before the Fed decided to go down the path of Quantitative Easing 2 (QE2), which is essentially a potential devaluation of the dollar.

How can Britain accomplish this? The Bank of England will have to print more money to help the current deficit crisis even as the government institutes austerity measures. We see that hand waving in the back. The question is, “Wouldn’t that be inflationary?”

Of course it would. That’s the plan. A little inflation, along with decreasing deficits, will result in a weaker currency and therefore (hopefully) more exports. In this way, England will grow its way out of the crisis. Of course, inflation means one can buy less with the domestic currency, especially from foreign markets. Those on fixed incomes get hurt, and maybe even savagely hurt, depending on the level of inflation, but the hope is that it will be mild inflation spread out over time, which is better for people (and governments) who are indebted.

Here is their dilemma. To reduce the government’s fiscal deficit, either private business must increase their deficits, the trade balance has to shift, or some combination. It is lucky for the United Kingdom that it can, in fact, allow the pound to drift lower by monetizing some of their debt—lucky in the sense that they can at least find a path out of their morass. Of course, that means that pound-denominated assets might drop by another third against the dollar. It means that the buying power of British citizens for foreign goods is crushed. British citizens on pensions in foreign countries could see their locally denominated incomes drop by half from their peak (well, not against the euro, which is also in free fall).

What’s the alternative? Keep running those massive deficits until ever-increasing borrowing costs blow a hole in your economy, reducing your currency valuation anyway. Remember that if you reduce government spending, in the short run, it will act as a drag on the economy, so you are guaranteeing slower growth in the short run. As I have been pointing out for a long time, countries around the world are down to no good choices.

Britain’s economic path could include a much slower economy (maybe another recession), much lower buying power for the pound, and lower real incomes for its workers, yet they have a path that they can get back on track in a few years. Because they have control of their currency and their debt, which is mostly in their own currency, they can devalue their way to a solution.

Some of my fondest memories were made in Greece. I like the country and the people. But they have made some bad choices and now must deal with the consequences.

We all know that Greek government deficits are somewhere around 14 percent. But their trade deficit is running north of 10 percent. (By comparison, the U.S. trade deficit is now about 4 percent.)

Going back to the equation, if Greece wants to reduce its fiscal deficit by 11 percent over the next three years, then either private debt must increase or the trade deficit must drop sharply. Those are the accounting rules.

But here’s the problem. Greece cannot devalue its currency. It is (for now) stuck with the euro. So how can they make their products more competitive? How do they grow their way out of their problems? How do they become more productive relative to the rest of Europe and the world?

Barring some new productivity boost in olive oil and produce production, there is no easy way. Since the beginning of the euro in 1999, Germany has become some 30 percent more productive than Greece. Very roughly, that means it costs 30 percent more to produce the same amount of goods in Greece than in Germany. That is why Greece imports $64 billion of goods and exports only $21 billion.

What needs to happen for Greece to become more competitive? Labor costs must fall by a lot, and not by just 10 or 15 percent. But if labor costs drop (deflation), then that means that taxes also drop. The government takes in less, and GDP drops. The perverse situation is that the debt-to-GDP ratio gets worse, even as they enact their austerity measures.

In short, Greek lifestyles are on the line. They are going to fall. They have no choice. They are going to willingly have to put themselves into a severe recession or, more realistically, a depression.

Just as British incomes relative to their competitors will fall, Greek labor costs must fall as well. But the problem for Greeks is that the costs they bear are still in euros. It becomes a most vicious spiral. The more cuts they make, the less income there is to tax, which means less government revenue, which means more cuts, and so on.

And the solution is to borrow more money they cannot at the end of the day hope to pay. All that is happening is that the day of reckoning is delayed in the hope for some miracle.

What are their choices? They can simply default on the debt. Stop making any payments. That means they cannot borrow any more money for a minimum of a few years (Argentina seemed to be able to come back fairly quickly after default), but it would go a long way toward balancing the government budget. Government employees would need to take large pay cuts, and there would be other large cuts in services. It would be a depression, but you work your way out of it. You are still in the euro and need to figure out how to become more competitive.

Or you could take the austerity, downsize your labor costs, and borrow more money, which means even larger debt service in a few years. Private citizens can go into more debt. (Remember, we have to have our balance!) This is also a depression.

Finally, you could leave the euro, which implies a devaluation. This is a very ugly scenario, as contracts are in euros. The legal bills would go on forever.

There are no good choices for the Greeks. No easy way. And then you wonder why people worry about contagion to Portugal and Spain?

We see that hand asking another question: Since the euro is falling, won’t that make Greece more competitive? The answer is yes and no. Yes, relative to the dollar and a lot of emerging market currencies but not to the rest of the European countries, which are their main trading partners. A falling euro just makes economic export power Germany and the other northern countries even more competitive.

Europe as a whole has a small trade surplus. But the bulk of it comes from a few countries. For Greece to reduce its trade deficit is a very large lifestyle change.

Germany is basically saying you should be like us. And everyone wants to be. Just not everyone can.

Every country cannot run a trade surplus. Someone has to buy. But the prescription that politicians want is for fiscal austerity and trade surpluses, at least for European countries. That is the import of Martin Wolf’s editorial we quoted previously. He is as wired in as you get in Britain. And in a few short sentences, he laid out the formula that Britain will pursue. Devalue and put your goods and services on sale. Figure out how to get to that surplus.

Germany has been thriving because much of Europe has been buying its goods. If the rest of Europe is forced by circumstances to buy less, that will not be good for Germany. It’s all connected.

Yet politicians want to believe that somehow we all can run surpluses, at least in their country. We can balance the budgets. We can reduce our private debts. We all want to believe in that mythical Lake Woebegone, where all the kids are above average. Sadly, it just isn’t possible for everyone to have a happy ending.

Before we leave this part of the chapter, here are a few thoughts about the situation in the United States. The mood in the country, if not in Washington (at least before the elections last November), is that the deficit needs to be brought down. Consumers are clearly increasing savings and cutting back on debt. But those accounts must balance. If we want to reduce the deficits and reduce our personal debt, we must then find a way to reduce the trade deficit, which is running about $500 billion a year as we write, or about $1 trillion less than the deficit.

First off, saving more, as we think likely, will mean less spending and thus fewer imports over time. But if the United States is going to really attempt to balance the budget over time, reduce our personal leverage, and save more, then we have to address the glaring need to import $300 billion in oil (give or take, depending on the price of oil).

This can only partially be done by offshore drilling. The real key is to reduce the need for oil. Nuclear power, renewables, and a shift to electric cars will be most helpful. Let us suggest something a little more radical. When the price of oil approached $4 a few years ago, Americans changed their driving and car-buying habits.

Perhaps we need to see the price of oil rise. What if we increased the price of oil with an increase in gas taxes by 2 or 3 cents a gallon each and every month until the demand for oil dropped to the point where we did not need foreign oil? If we had European gas mileage standards, that would be the case now.

And take that 2 or 3 cents and dedicate it to fixing our infrastructure, which is badly in need of repair. In fact, the U.S. Infrastructure Report Card (www.infrastructurereportcard.org) grades the United States on a variety of factors (and the link has a very informative short video). Done by the American Society of Civil Engineers, the 2009 grades include:

| Aviation (D) | Hazardous Waste (D) | Roads (D−) |

| Bridges (C) | Inland Waterways (D−) | Schools (D) |

| Dams (D) | Levees (D−) | Solid Waste (C+) |

| Drinking Water (D−) | Public Parks and Recreation (C−) | Transit (D) |

| Energy (D+) | Rail (C−) | Wastewater (D−) |

Overall, America’s infrastructure GPA was graded a D. To get to an A requires a five-year infrastructure investment of $2.2 trillion.

That infrastructure has to be paid for, and we need to buy less oil. We know price makes a difference, and the majority of that 2 or 3 cents needs to stay in the United States, where it was taxed, and forbidden to be used on anything other than infrastructure. (And while we are at it, why not build 50 nuclear plants now? We’ll get into this and more when we get to the chapter on the way back for the United States.)

The Competitive Currency Devaluation Raceway

Greg Weldon described the competitive currency devaluations in Asia in the middle of the last decade as similar to that of a NASCAR race. Each country tried to get in the draft of the other countries, keeping their currency and selling power more or less in line as they tried to market their products to the United States and Europe. This is a form of mercantilism, where countries encourage exports and, by reducing the value of their currencies, discourage imports. It also helps explain the massive current account surpluses building up in emerging market countries, especially in Asia.

There is the real potential for this race to become far more competitive. Indeed, Martin Wolf’s few sentences are the equivalent of the NASCAR announcer saying, “Gentlemen, start your engines.”

We touched on Britain. But there are structural weaknesses in the euro as well (again, discussed in later chapters). In the early part of the last decade, when the euro was at $0.88, John wrote that the euro would rise to $1.50 (seemingly unattainable at the time) and then fall back to parity with the dollar by the middle of this decade. He was an optimist, as the euro went to $1.60 but is now retracing that rise.

The title for the chapter on Japan is “A Bug in Search of a Windshield.” While the currency of the Land of the Rising Sun is very strong as we write, there are real structural reasons, as well as political ones, that lead us to predict that the yen will begin to weaken. At first, it will be gradual. But without real reform in government expenditures, the yen could weaken substantially. A fall of 50 percent or more against the dollar by the middle of this decade (if not sooner) is quite thinkable.

The euro at parity. The pound at parity. The value of the yen cut in half. What is the response of emerging market countries around the world? Do they sit by and allow their currencies to rise and make it more difficult to compete with Europe and Japan? The Swiss are clearly not happy with the rise of the Swiss franc. The Scandinavian countries? The rest of Asia?

And now the Fed is embarking on QE2 under the guise of fighting deflation and a possible slowing of the economy into recession, but one of the outcomes will be a lower dollar as we put our own car into the competitive devaluation raceway. And as long as the Fed is printing, all bets are off as to who will win the race to the bottom.

And what of China? Europe is an extremely important market to them. Do they sit by and let their currency rise (a lot!) against the euro and hurt their exports? But if they react, then that makes the United States unhappy and starts another competitive devaluation throughout Asia.

What does the United States do? Its senators are mad enough about the valuation of the Chinese yuan. Do Schumer, Graham, and colleagues start talking about tariffs on European goods? On Japanese goods?

The United States and the world went into a deep recession in the early 1930s, but it took the protectionist Smoot-Hawley Act to stretch it out into a prolonged recession. It was a beggar-thy-neighbor policy that swept the world. It was disastrous and sowed the seeds for World War II. There was an unintended consequence on every page of that bill.

In a few years, the world will be at a significant risk of protectionist policies damaging world trade. Let us hope that cool heads will be at the forefront and avoid the policies that so clearly would hurt all.

This chapter has been a kind of introduction to the macroeconomic forces that are at play in the world in which we find ourselves. While much of the developed world has no good choices, we (each country on its own) still must decide on a path forward. We can choose between bad choices and what will be disastrous choices. We can make the best of what we have created and move on. If we make the correct choices to solve the structural problems, we can emerge with a brighter future for ourselves and our children. If we choose to avoid the problems, we will hit the wall in spectacular and dramatic fashion.

As Ollie said to Stan (Laurel and Hardy), “Here’s another nice mess you’ve gotten me into!” A nice mess indeed!

And now, let’s spend the next few chapters examining some of the problems we face.

1Some people like my friend Martin Barnes from BCA say government debt is never really repaid—it is in effect a giant Ponzi scheme. The way to avoid a crisis is to prevent the Ponzi scheme from spiraling out of control.

2We are reminded of the improbable story of Fred Smith, the founder of FedEx, who early in the history of the company could not make payroll. So he flew to Las Vegas and wagered what little cash they had, and incredibly made enough ($27,000) to keep the company alive. Not exactly orthodox investment banking procedure, but it is illustrative of the crazy, gung-ho nature of some entrepreneurs. Between 50 and 80 percent of all business start-ups in the United States do not exist after five years, depending on your source for the data. We guess Fred figured he could get better odds in Vegas. Starting a business is fraught with peril. Getting the cash is one of the larger problems.

3We are not against a healthy government sector. But when government becomes too big or absorbs too great a share of private savings, it chokes off productivity and growth. And that hurts job creation. That is especially true when a government runs large fiscal deficits.