CHAPTER FIVE

This Time Is Different

Our immersion in the details of crises that have arisen over the past eight centuries and in data on them has led us to conclude that the most commonly repeated and most expensive investment advice ever given in the boom just before a financial crisis stems from the perception that “this time is different.” That advice, that the old rules of valuation no longer apply, is usually followed up with vigor. Financial professionals and, all too often, government leaders explain that we are doing things better than before, we are smarter, and we have learned from past mistakes. Each time, society convinces itself that the current boom, unlike the many booms that preceded catastrophic collapses in the past, is built on sound fundamentals, structural reforms, technological innovation, and good policy.

—Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, This Time Is Different

Capitalism without failure is like religion without sin.

—Charles Kindleberger, Manias, Panics and Crashes

When does a potential crisis become an actual crisis, and how and why does it happen? Why did almost everyone believe there were no problems in the U.S. (or Japanese or European or British) economies in 2006? Yet now we are mired in a very difficult situation. “The subprime problem will be contained,” said Fed Chairman Bernanke, just months before the implosion and significant Fed intervention.

This chapter will attempt to distill the data assembled and the wisdom contained in a very important book by Professors Carmen Reinhart (of the University of Maryland) and Ken Rogoff (of Harvard University), which has catalogued more than 250 financial crises in 66 countries over 800 years and then analyzed them for differences and similarities.1 The database the authors have assembled is a first. What it does is allow us to see what has actually happened in a crisis rather than making assumptions (which assume away the real world—a favorite pastime of economists) or using theories that don’t seem to work out in the real world.

Rogoff was at the International Monetary Fund as the chief economist and director of research, and he persuaded Reinhart to join him as deputy director. It was the beginning of a collaboration in the exploration of the history of debt and crises that has given us so much new material. It is difficult to overstate the importance of this book, as heretofore we dealt with anecdotal evidence about crises. Their assembled data is a treasure trove of knowledge. The authors have conveniently organized the book so that one can read the first and the last five chapters, purposefully allowing people to get the main points without drilling into the mountain of details they provide. We strongly suggest you get the book and read it! Our summary in no way does justice to the sweep and scope of the book.

This is also a very sobering book. It does not augur well as for the ability of the developed world to blithely exit from our woes. This Time Is Different gives evidence to one of the main points of this book: that we have a lot of pain to experience because of the bad choices we have made. This pain will be felt throughout the entire developed world to varying degrees, and the emerging world will suffer, too, as we go through it. It is not a matter of pain or no pain. There is no way to avoid it. It is simply a matter of when and over how long a period we deal with the pain.

In fact, Reinhart and Rogoff’s research suggests that the longer we try to put off the pain, the worse the total pain will be. We have simply overleveraged ourselves, and the deleveraging process will not be fun, whether on a personal or sovereign level.

We are going to look at several quotes from the book, as well as an extensive interview they graciously granted. We have also taken the great liberty of mixing paragraphs from various chapters that we feel are important. Please note that all the emphasis is our editorial license. Let’s start by looking at part of their conclusion, which we think eloquently sums up the problems we face:

The lesson of history, then, is that even as institutions and policy makers improve, there will always be a temptation to stretch the limits. Just as an individual can go bankrupt no matter how rich she starts out, a financial system can collapse under the pressure of greed, politics, and profits no matter how well regulated it seems to be. Technology has changed, the height of humans has changed, and fashions have changed.

Yet the ability of governments and investors to delude themselves, giving rise to periodic bouts of euphoria that usually end in tears, seems to have remained a constant. No careful reader of Friedman and Schwartz will be surprised by this lesson about the ability of governments to mismanage financial markets, a key theme of their analysis.

As for financial markets, we have come full circle to the concept of financial fragility in economies with massive indebtedness. All too often, periods of heavy borrowing can take place in a bubble and last for a surprisingly long time. But highly leveraged economies, particularly those in which continual rollover of short-term debt is sustained only by confidence in relatively illiquid underlying assets, seldom survive forever, particularly if leverage continues to grow unchecked.

This time may seem different, but all too often a deeper look shows it is not. Encouragingly, history does point to warning signs that policy makers can look at to assess risk—if only they do not become too drunk with their credit bubble–fueled success and say, as their predecessors have for centuries, “This time is different.”

Sadly, the lesson is not a happy one. There are no good endings once you start down a deleveraging path. As I have been writing for several years, much of the entire developed world is now faced with choosing from among several bad choices, some being worse than others. This Time Is Different offers up some ideas as to which are the worst choices.

There seems to be no magic point at which a crisis develops. Things go along, and then the bond market loses confidence, seemingly in a short period. It is that ephemeral quality of confidence that is crucial to the operation of a bond market and the lack thereof that so quickly erodes any semblance of its normal functioning. Without confidence, the ability to roll over debt or borrow new debt at affordable rates collapses, as does the liquidity in the financial markets and the economy. It is a sad story that has been repeated over and over again over the centuries. We think we have progressed, but as previous chapters have demonstrated, we can no more repeal the basic laws of economics than we can repeal the law of gravity.

Let’s jump to an interview John did with the authors:

KENNETH ROGOFF: One of the epiphanies that I had sort of in the process of doing the book and Carmen may well have had this epiphany a decade before me, but it was that a lot of the academic writing on debt and the research on debt is about, “Gosh it’s tough. We’re giving this debt to our children and we should really care about our children and our grandchildren and if we run big debts that’s not a good thing.” There was a Nobel Prize given a couple of decades ago to James Buchannan basically for his writings about learning about debt and how to think about it. But you know the fact is that when you run these big debts, the problem is not with your children or your grandchildren, it’s in your lifetime. If you get to really high debt levels, you don’t make it. The market eventually gets concerned. They get concerned about whether your grandchildren or your children are going to pay, and suddenly interest rates go up and you run into problems. But you are absolutely right, this is something in our lifetime, not necessarily a debt crisis, but we have to deal with it. It’s not something we can just put off completely to our children.

CARMEN REINHART: Let me just add to that. I think one of the reasons to be concerned right now about debt issues is that it cuts across both the public sector and the private sector. The last time that the U.S. and some of the major advanced economies had debt levels that encroach on where we are now was around World War II. And around World War II, the private sector was lean and mean; they had worked down their debts during the depression and during the war. But now everyone is indebted.

JOHN MAULDIN: Yes, and what is happening, it seems, is that the government is trying to step in and take up the slack as the private sector reduces its leverage, and so overall leverage in the economy is not being reduced; it’s actually growing. And with your work—and this was one of the things that kind of struck me—it’s the combined debt. It’s not just government debt or private debt, it’s that combined debt that gets to a point where something has to give. Leverage has to go down, it has to be defaulted on, you’ve got to—we don’t want to use the word austerity too much, but you’ve got to start paying it down. You’ve reached an end point.

KENNETH ROGOFF: It’s particularly external debt that you owe to foreigners that is particularly an issue. Where the private debt so often, especially for emerging markets, but it could well happen in Europe today, where a lot of the private debt ends up getting assumed by the government and you say, but the government doesn’t guarantee private debts; well, no, they don’t. We didn’t guarantee all the financial debt either before it happened, yet we do see that. I remember when I was first working on the 1980s Latin Debt Crisis and piecing together the data there on what was happening to public debt and what was happening to private debt, and I said, gosh the private debt is just shrinking and shrinking, isn’t that interesting. Then I found out that it was being “guaranteed” by the public sector, who were in fact assuming the debts to make it easier to default on.

Now back to the book:

If there is one common theme to the vast range of crises we consider in this book, it is that excessive debt accumulation, whether it be by the government, banks, corporations, or consumers, often poses greater systemic risks than it seems during a boom. Infusions of cash can make a government look like it is providing greater growth to its economy than it really is. Private-sector borrowing binges can inflate housing and stock prices far beyond their long-run sustainable levels and make banks seem more stable and profitable than they really are. Such large-scale debt buildups pose risks because they make an economy vulnerable to crises of confidence, particularly when debt is short term and needs to be constantly refinanced. Debt-fueled booms all too often provide false affirmation of a government’s policies, a financial institution’s ability to make outsize profits, or a country’s standard of living. Most of these booms end badly. Of course, debt instruments are crucial to all economies, ancient and modern, but balancing the risk and opportunities of debt is always a challenge, a challenge that policy makers, investors, and ordinary citizens must never forget.

And this is key. Read it twice (at least!):

Perhaps more than anything else, failure to recognize the precariousness and fickleness of confidence—especially in cases in which large short-term debts need to be rolled over continuously—is the key factor that gives rise to the this-time-is-different syndrome. Highly indebted governments, banks, or corporations can seem to be merrily rolling along for an extended period, when bang!—confidence collapses, lenders disappear, and a crisis hits.

Economic theory tells us that it is precisely the fickle nature of confidence, including its dependence on the public’s expectation of future events, which makes it so difficult to predict the timing of debt crises. High debt levels lead, in many mathematical economics models, to “multiple equilibria” in which the debt level might be sustained—or might not be. Economists do not have a terribly good idea of what kinds of events shift confidence and of how to concretely assess confidence vulnerability. What one does see, again and again, in the history of financial crises is that when an accident is waiting to happen, it eventually does. When countries become too deeply indebted, they are headed for trouble. When debt-fueled asset price explosions seem too good to be true, they probably are. But the exact timing can be very difficult to guess, and a crisis that seems imminent can sometimes take years to ignite.

How confident was the world in October 2006? John was writing that there would be a recession, a subprime crisis, and a credit crisis in our future. He was on Larry Kudlow’s show with Nouriel Roubini, and Larry and John Rutledge were giving him a hard time about his so-called doom and gloom. “If there is going to be a recession, you should get out of the stock market” was John’s call. He was a tad early, as the market proceeded to go up another 20 percent over the next eight months. And then the crash came.

But that’s the point. There is no way to determine when the crisis comes.

As Reinhart and Rogoff wrote:

Highly indebted governments, banks, or corporations can seem to be merrily rolling along for an extended period, when bang!—confidence collapses, lenders disappear, and a crisis hits.

Bang is the right word. It is the nature of human beings to assume that the current trend will work out, that things can’t really be that bad. The trend is your friend until it ends. Look at the bond markets only a year and then just a few months before World War I. There was no sign of an impending war. Everyone knew that cooler heads would prevail.

We can look back now and see where we made mistakes in the current crisis. We actually believed that this time was different, that we had better financial instruments, smarter regulators, and were so, well, modern. Times were different. We knew how to deal with leverage. Borrowing against your home was a good thing. Housing values would always go up. And so on.

Now, there are bullish voices telling us that things are headed back to normal. Mainstream forecasts for GDP growth this year (2010) are quite robust, north of 4 percent for the year, based on evidence from past recoveries. However, the underlying fundamentals of a banking crisis are far different from those of a typical business-cycle recession, as Reinhart and Rogoff’s work so clearly reveals. It typically takes years to work off excess leverage in a banking crisis, with unemployment often rising for four years running.1

It’s the Deleveraging, Stupid!

The reason this recession is different is that it is a deleveraging recession. We borrowed too much (all over the developed world) and now have to repair our balance sheets as the assets (housing, bonds, securities, etc.) we bought have fallen in value. A new and very interesting (if somewhat long) study by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) found that periods of overleveraging are often followed by six to seven years of slow growth as the deleveraging process plays out. No quick fixes.

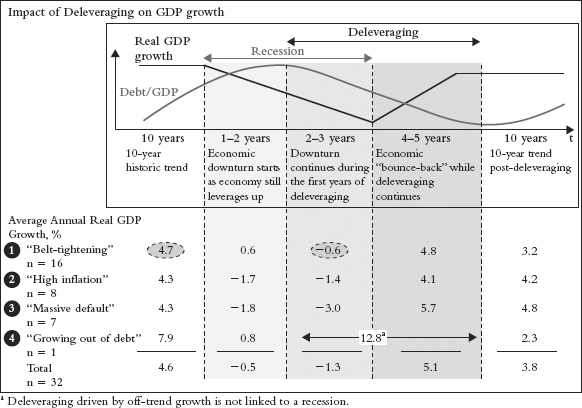

Figure 5.1 shows the phases of deleveraging.

Figure 5.1 Real GDP Growth Is Significantly Slower in the First Two to Three Years of Deleveraging

Source: International Monetary Fund, McKinsey Global Institute analysis.

Let’s look at some of their main conclusions (and they have a solid 10-page executive summary, worth reading.) This analysis adds new details to the picture of how leverage grew around the world before the crisis and how the process of reducing it could unfold.

- Leverage levels are still very high in some sectors of several countries—and this is a global problem, not just a U.S. one.

- To assess the sustainability of leverage, one must take a granular view using multiple sector-specific metrics. The analysis has identified 10 sectors within five economies that have a high likelihood of deleveraging.

- Empirically, a long period of deleveraging nearly always follows a major financial crisis.

- Deleveraging episodes are painful, lasting six to seven years on average and reducing the ratio of debt to GDP by 25 percent. Typically, GDP contracts during the first several years and then recovers.

- If history is a guide, many years of debt reduction are expected in specific sectors of some of the world’s largest economies, and this process will exert a significant drag on GDP growth.

- Coping with pockets of deleveraging is also a challenge for business executives. The process portends a prolonged period in which credit is less available and costlier, altering the viability of some business models and changing the attractiveness of different types of investments. In historic episodes, private investment was often quite low for the duration of deleveraging. Today, the household sectors of several countries have a high likelihood of deleveraging. If this happens, consumption growth is likely to be slower than the pre-crisis trend, and spending patterns will shift. Consumer-facing businesses have already seen a shift in spending toward value-oriented goods and away from luxury goods, and this new pattern may persist while households repair their balance sheets. Business leaders will need flexibility to respond to such shifts.2

The Lex column in the Financial Times observed, concerning the report:

It may be economically and politically sensible for governments to spend money on making life more palatable at the height of the crisis. But the longer countries go on before paying down their debt, the more painful and drawn-out the process is likely to be. Unless, of course, government bond investors revolt and expedite the whole shebang.3

And that is the crux of the matter. We have to raise more than $1 trillion annually in the United States from domestic sources for as far as the Budget Office makes its projections. Great Britain has the GDP-equivalent task. So does much of Europe. Japan is simply off the radar. Japan, as John has noted, is a bug in search of a windshield.

Sometime in the coming few years, the bond markets of the world will be tested. Normally, a deleveraging cycle would be deflationary, and lower interest rates would be the outcome. But in the face of such large deficits, with no home-grown source to meet them? That worked for Japan for 20 years, as their domestic markets bought their debt. But that process is coming to an end.

James Carville once famously remarked that when he died, he wanted to come back as the bond market, because that is where the real power is. And we think we will find out all too soon what the bond vigilantes have to say.

The point is that complacency almost always ends suddenly. You just don’t slide gradually into a crisis, over years. It happens! All of a sudden, there is a trigger event, and it is August 2008. And the evidence in the book is that things go along fine until there is that crisis of confidence. There is no way to know when it will happen. There is no magic debt level, no magic drop in currencies, no percentage level of fiscal deficits, no single point where we can say, “This is it.” It is different in different crises.

One point we found fascinating. When it comes to the various types of crises the authors identify, there is very little difference between developed and emerging-market countries, especially as to the fallout. It seems that the developed world has no corner on special wisdom that would allow crises to be avoided or allow quicker recovery. In fact, because of their overconfidence—because they actually feel they have superior systems—developed countries can dig deeper holes for themselves than emerging markets.

Oh, and the Fed should have seen this crisis coming. The authors point to some very clear precursors to debt crises.

As we will show, the outsized U.S. borrowing from abroad that occurred prior to the crisis (manifested in a sequence of gaping current account and trade balance deficits) was hardly the only warning signal. In fact, the U.S. economy, at the epicenter of the crisis, showed many other signs of being on the brink of a deep financial crisis. Other measures such as asset price inflation, most notably in the real estate sector, rising household leverage, and the slowing output—standard leading indicators of financial crises—all revealed worrisome symptoms. Indeed, from a purely quantitative perspective, the run-up to the U.S. financial crisis showed all the signs of an accident waiting to happen.

Of course, the United States was hardly alone in showing classic warning signs of a financial crisis, with Great Britain, Spain, and Ireland, among other countries, experiencing many of the same symptoms.

On the one hand, the Federal Reserve’s logic for ignoring housing prices was grounded in the perfectly sensible proposition that the private sector can judge equilibrium housing prices (or equity prices) at least as well as any government bureaucrat. On the other hand, it might have paid more attention to the fact that the rise in asset prices was being fueled by a relentless increase in the ratio of household debt to GDP, against a backdrop of record lows in the personal saving rate. This ratio, which had been roughly stable at close to 80 percent of personal income until 1993, had risen to 120 percent in 2003 and to nearly 130 percent by mid-2006. Empirical work by Bordo and Jeanne and the Bank for International Settlements suggested that when housing booms are accompanied by sharp rises in debt, the risk of a crisis is significantly elevated. Although this work was not necessarily definitive, it certainly raised questions about the Federal Reserve’s policy of benign neglect.

The U.S. conceit that its financial and regulatory system could withstand massive capital inflows on a sustained basis without any problems arguably laid the foundations for the global financial crisis of the late 2000s. The thinking that “this time is different”—because this time the U.S. had a superior system—once again proved false. Outsized financial market returns were in fact greatly exaggerated by capital inflows, just as would be the case in emerging markets. What could in retrospect be recognized as huge regulatory mistakes, including the deregulation of the subprime mortgage market and the 2004 decision of the Securities and Exchange Commission to allow investment banks to triple their leverage ratios (that is, the ratio measuring the amount of risk to capital), appeared benign at the time. Capital inflows pushed up borrowing and asset prices while reducing spreads on all sorts of risky assets, leading the International Monetary Fund to conclude in April 2007, in its twice-annual World Economic Outlook, that risks to the global economy had become extremely low and that, for the moment, there were no great worries. When the international agency charged with being the global watchdog declares that there are no risks, there is no surer sign that this time is different.

By that, Reinhart and Rogoff mean that the attitude of the market in general and central bankers in particular was that “this time is different,” and so we did not need to worry about the warning signs. The entire point of the book is that it is never different. We just somehow believe we are in a special situation.

We have focused on macroeconomic issues, but many problems were hidden in the “plumbing” of the financial markets, as has become painfully evident since the beginning of the crisis. Some of these problems might have taken years to address. Above all, the huge run-up in housing prices—over 100 percent nationally over five years—should have been an alarm, especially fueled as it was by rising leverage. At the beginning of 2008, the total value of mortgages in the United States was approximately 90 percent of GDP. Policy makers should have decided several years prior to the crisis to deliberately take some steam out of the system. Unfortunately, efforts to maintain growth and prevent significant sharp stock market declines had the effect of taking the safety valve off the pressure cooker.

Remember the illustration we used in Chapter 1 about the difference between small fires in Baja California and large destructive fires in California proper? Trying to prevent small crises only leads to bigger ones if the system is not allowed to operate freely.

The signals approach (or most alternative methods) will not pinpoint the exact date on which a bubble will burst or provide an obvious indication of the severity of the looming crisis. What this systematic exercise can deliver is valuable information as to whether an economy is showing one or more of the classic symptoms that emerge before a severe financial illness develops. The most significant hurdle in establishing an effective and credible early warning system, however, is not the design of a systematic framework that is capable of producing relatively reliable signals of distress from the various indicators in a timely manner. The greatest barrier to success is the well-entrenched tendency of policy makers and market participants to treat the signals as irrelevant archaic residuals of an outdated framework, assuming that old rules of valuation no longer apply. If the past we have studied in this book is any guide, these signals will be dismissed more often than not. That is why we also need to think about improving institutions.

. . . Second, policy makers must recognize that banking crises tend to be protracted affairs. Some crisis episodes (such as those of Japan in 1992 and Spain in 1977) were stretched out even longer by the authorities by a lengthy period of denial.

The evidence was there. So why did the Fed miss it?

A pointed critique is leveled at the Fed and Greenspan, and at Bernanke in particular, by Andrew Smithers in his powerful book (now updated) Wall Street Revalued: Imperfect Markets and Inept Central Bankers. The foreword is by one of our favorite analysts, Jeremy Grantham. This ties nicely into the themes explored by Reinhart and Rogoff.

The book is a withering critique of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), among other economic theories. Smithers argues that because the tenets of EMH are so ingrained, Greenspan and Bernanke could not recognize the bubble, because they believed in the efficiency of markets. “Dismissing financial crisis on the grounds that bubbles and busts cannot take place because that would imply irrationality is to ignore a condition for the sake of theory.” Which they did.

As Grantham wrote in the foreword:

My own favorite illustration of their views was Bernanke’s comment in late 2006 at the height of a 3-sigma (100-year) event in a US housing market that had no prior housing bubbles: “The US housing market merely reflects a strong US economy.” He was surrounded by statisticians and yet could not see the data. . . . His profound faith in market efficiency, and therefore a world where bubbles could not exist, made it impossible for him to see what was in front of his own eyes.4

Reinhart and Rogoff show time and time again that bubbles always end in tears. Markets and investors are, in fact, irrational. What kind of Fed governor would it have taken to suggest that housing was in a bubble and we were going to have to take steps to slow it down—raising rates, analyzing securitization and ratings? It would have taken one tough hombre. In fact, we had Greenspan, who encouraged the unchecked expansion of the securitized derivatives market. And a Congress that would not allow proper supervision of Fannie and Freddie (which is going to cost U.S. taxpayers on the order of $400 billion). The list is long.

Some Parting Words from Rogoff and Reinhart

And in the coming crisis? Who will step forward and channel their inner Paul Volcker, forcing the economy back from the precipice?

Let’s finish this chapter with a few paragraphs from the end of the interview John did with Rogoff and Reinhart:

JOHN MAULDIN: Well let’s bring that back now to the U.S. and our situation. We’re not without some choices, but our choices to me seem to be either take the Japanese direction and end up where Japan does in something unsustainable or to begin to gradually, but significantly, reducing the debt. We’re not going to take the Austrian solution and just shut it all down and throw ourselves into a depression. But somehow or another, we’ve got to show some fiscal discipline so that the bond market will behave. Is that your assessment as well? Or do you see a different path for us?

CARMEN REINHART: I don’t think we have as much time as Japan. We are borrowing from the rest of the world, and our saving rates are pretty low despite the anemic uptake we’ve had, which seems huge from a recent standpoint, but it’s anemic by historic standards. So we don’t have as much time as Japan does.

JOHN MAULDIN: Really? [As in I was both shocked and scared!]

CARMEN REINHART: I think that if you look at the more aggregated debt picture in the United States, there are outside—I was listening to some analysts who are fluent in an area that I am not, which is state finances. And we of course all know about California, but what was alarming about their presentation was that they had tiered up the various states that had debt problems of different degrees. What I’m getting at is the debt situation in the United States, on the whole, doesn’t offer you I think the length of time that many politicians think we have because of the reasons I just enumerated.

KENNETH ROGOFF: I would say that virtually every country in the world is grappling right now with how fast we get out of our fiscal stimulus and how much do we worry about this longer term problem of debt. And I fear that altogether too many countries will wait too long, which doesn’t mean you end up getting forced to default, it just means the choices get more painful. Something we just find as a recurrent theme, is you’re just rolling along, borrowing money and it seems okay, and that’s what a lot of people say and wham, you hit some limit. No one knows where it is, what it is, but we know you hit it. Carmen and I do have numbers of what are really high debts and what aren’t. And the U.S. will hit that [limit] and there are people who say it is not a problem and everyone loves us, greatest country in the world, where else will the Chinese invest? And you want to hear a great “this time it’s different” theme that’s a new one.

John, you started out this conversation on how we got started in this research and this was one of the things in our 2003 paper that is now built into the early chapter or two of the book that just got us really excited was this realization of how not only theoretically but quantitatively you see it, that countries have the threshold that they hit that we’ve found ways to try and crudely measure, where the interest rates you’re charged just explode.

It was an epiphany for us because it helped us understand in a really clear way, why it was that the IMF program that we were involved with, and watching and commenting on, so many of them seemed to run awry. We would be presented with this calculation with, “Oh well, their debt is 50 percent, and we’re going to let them go slow and run it up to 55 percent before we start getting it down.” But you know if they are running into trouble at 50 percent, and you let it go up to 55 percent, the interest rate could just explode on you as the markets just don’t have confidence. And then in our more recent works that we just finished, this paper, “Growth in a Time of Debt,” we found that there was a parallel effect for advanced countries where they hit these growth limits at 90 and 100 percent.

And just again and again, this theme that there is a ceiling out there, and absolutely what Carmen said was right. We do know something about it, there is a big standard error around it, but if you don’t owe any money, you don’t have to worry if the market loses confidence and what kind of debtor you are going to be. And if you owe a ton of money, especially if you borrowed a lot short term, you’ve got a lot to worry about, and in our more recent work we were able to sort of demonstrate that somewhat more indirectly, but nevertheless feel that we really saw evidence of that. Not only for emerging markets, but for advanced countries like the United States.

CARMEN REINHART: Let me make a remark that sort of highlights my wet rag personality. One of the emphases in our analysis is that you do have these long cycles of indebtedness. Both the buildup and the unwinding show a lot of persistence; it’s not quick. During the buildup phase, this is when we are all geniuses. We are all geniuses because usually asset prices are going up and growth is buoyant. I think without even calling on extreme scenarios, I think if you look not just at the United States, but the global situation, apart from some emerging markets, which in the past few years have delivered. There is a lot of public and private debt so that on the public side, you can’t expect continued stimulus because they actually have debt problems that are actually pushing them in the other direction. And on the private side, if you look at the historical statistics in the United States on the last piece that Ken and I did, we plot those statistics since 1916 for the United States. And we haven’t been as levered, not withstanding whatever deleveraging we have seen in the very recent past; we are still highly, highly leveraged as a nation. And the same can be said for most other advanced economies. So what am I getting at to your question, John, is that I think we are in for a period of subpar growth. And in a period of subpar growth, I think that it is not something that you are going to have the same kind of investment environment that we had in the run-ups to the IT bubble and in the run-ups to the subprime crisis. I think it’s going to be a different, more sobering environment.

JOHN MAULDIN: It’s what I call a muddle through economy. It makes it very, very difficult for us to say we’re going to grow our way out of this problem. But Carmen, what you seem to be saying—and maybe Ken as well—is unless we really do something much quicker. Quite frankly when you said we don’t have as much time as the Japanese, that was very disconcerting to me. What you are suggesting is that interest rates could take a run up in a deflationary environment that we are in right now, which seems almost is a contradiction.

KENNETH ROGOFF: I just want to say something a little calmer, but not necessarily calm, but reinforcing what Carmen said. Slow growth is here, that’s just [comes] with this debt, no matter what way you turn. Greece is extreme, but they’ve got to tighten their belt and whatever they figure out how to get help, doing it gradually or whether they do it quickly, they’ve got to tighten their belt and it’s going to mean slower growth. It’s going to mean raising taxes, etc. Same thing in many, many countries in the world, it’s a matter of figuring out the timing. Some countries won’t tighten their belts soon enough, won’t figure out how to do it. They will actually go to the IMF first and then after failures with the IMF, eventually some of them will even default. But with the slow growth, whatever way you turn, you tighten your belt. Barring certainly a great, unbelievable period of technology growth or a friend from outer space helping us out, we do face slow growth, as Carmen said. I don’t know if that means you want to jump on it faster, hyperfast, but it certainly is something to be aware of in planning for everyone.

1Reinhart and Rogoff’s work assesses only federal debt. If you add in state and local debt, which must be paid for by the same tax base, it is actually worse than the federal numbers indicate.