CHAPTER SIX

The Future of Public Debt

An Unsustainable Path

Those who are most commonly creditors of a nation are, generally speaking, enlightened men; and there are signal examples to warrant a conclusion that when a candid and fair appeal is made to them, they will understand their true interest too well to refuse their concurrence in such modifications of their claims, as any real necessity may demand.

—Alexander Hamilton, Report on Public Credit, January 9, 1790

Our argument in Endgame is that while the debt supercycle is still growing on the back of increasing government debt, there is an end to that process, and we are fast approaching it. It is a world where not only will expanding government spending have to be brought under control but also it will actually have to be reduced.

In this chapter, we will look at a crucial report, “The Future of Public Debt: Prospects and Implications,” by Stephen G. Cecchetti, M. S. Mohanty, and Fabrizio Zampolli, published by the Bank of International Settlements (BIS).1 The BIS is often thought of as the central banker to central banks. It does not have much formal power, but it is highly influential and has an esteemed track record; after all, it was one of the few international bodies that consistently warned about the dangers of excessive leverage and extremes in credit growth. Although the BIS is quite conservative by its nature, the material covered in this paper is startling to those who read what are normally very academic and dense journals. Specifically, it looks at fiscal policy in a number of countries and, when combined with the implications of age-related spending (public pensions and health care), determines where levels of debt in terms of GDP are going.

Throughout this chapter, we are going to quote extensively from the paper, as we let the authors’ words speak for themselves. We’ll also add some of our own color and explanation as needed. (Please note that all emphasis in bold is our editorial license and that we have chosen to retain the original paper’s British spelling of certain words.)

After we look at the BIS paper, we will also look at the issues it raises and the implications for public debt. If public debt is unsustainable and the burden on government budgets is too great, what does this mean for government bonds? The inescapable conclusion is that government bonds currently are a Ponzi scheme. Governments lack the ability to reduce debt levels meaningfully, given current commitments. Because of this, we are likely to see “financial oppression,” whereby governments will use a variety of means to force investors to buy government bonds even as governments actively work to erode their real value. It doesn’t make for pretty reading, but let’s jump right in.

But before we start, let’s explain a few of the terms the BIS will use. They can sound complicated, but they’re not that hard to understand. There is a big difference between the cyclical versus structural deficit. The total deficit is the structural plus cyclical.

Governments tax and spend every year, but in the good years, they collect more in taxes than in the bad years. In the good years, they typically spend less than in the bad years. That is because spending on unemployment insurance, for example, is something the government does to soften the effects of a downturn. At the lowest point in the business cycle, there is a high level of unemployment. This means that tax revenues are low and spending is high. On the other hand, at the peak of the cycle, unemployment is low, and businesses are making money, so everyone pays more in taxes. The additional borrowing required at the low point of the cycle is the cyclical deficit.

The structural deficit is the deficit that remains across the business cycle, because the general level of government spending exceeds the level of taxes that are collected. This shortfall is present regardless of whether there is a recession.

Now let’s throw out another term. The primary balance of government spending is related to the structural and cyclical deficits. The primary balance is when total government expenditures, except for interest payments on the debt, equal total government revenues. The crucial wrinkle here is interest payments. If your interest rate is going up faster than the economy is growing, your total debt level will increase.

The best way to think about governments is to compare them to a household with a mortgage. A big mortgage is easier to pay down with lower monthly mortgage payments. If your mortgage payments are going up faster than your income, your debt level will only grow. For countries, it is the same. The point of no return for countries is when interest rates are rising faster than their growth rates. At that stage, there is no hope of stabilizing the deficit. This is the situation many countries in the developed world now find themselves in.

Our projections of public debt ratios lead us to conclude that the path pursued by fiscal authorities in a number of industrial countries is unsustainable. Drastic measures are necessary to check the rapid growth of current and future liabilities of governments and reduce their adverse consequences for long-term growth and monetary stability.

Drastic measures is not language you typically see in an economic paper from the Bank for International Settlements. But the picture painted in a very concise and well-written report by the BIS for 12 countries they cover is one for which the words drastic measures are well warranted.

The authors start by dealing with the growth in fiscal (government) deficits and the growth in debt. The United States has exploded from a fiscal deficit of 2.8 percent to 10.4 percent today, with only a small 1.3 percent reduction for 2011 projected. Debt will explode (the correct word!) from 62 percent of GDP to an estimated 100 percent of GDP by the end of 2011 or soon thereafter. The authors don’t mince words. They write at the beginning of their work:

The politics of public debt vary by country. In some, seared by unpleasant experience, there is a culture of frugality. In others, however, profligate official spending is commonplace. In recent years, consolidation has been successful on a number of occasions. But fiscal restraint tends to deliver stable debt; rarely does it produce substantial reductions. And, most critically, swings from deficits to surpluses have tended to come along with either falling nominal interest rates, rising real growth, or both. Today, interest rates are exceptionally low and the growth outlook for advanced economies is modest at best. This leads us to conclude that the question is when markets will start putting pressure on governments, not if.

When, in the absence of fiscal actions, will investors start demanding a much higher compensation for the risk of holding the increasingly large amounts of public debt that authorities are going to issue to finance their extravagant ways? In some countries, unstable debt dynamics, in which higher debt levels lead to higher interest rates, which then lead to even higher debt levels, are already clearly on the horizon.

It follows that the fiscal problems currently faced by industrial countries need to be tackled relatively soon and resolutely. Failure to do so will raise the chance of an unexpected and abrupt rise in government bond yields at medium and long maturities, which would put the nascent economic recovery at risk. It will also complicate the task of central banks in controlling inflation in the immediate future and might ultimately threaten the credibility of present monetary policy arrangements.

While fiscal problems need to be tackled soon, how to do that without seriously jeopardizing the incipient economic recovery is the current key challenge for fiscal authorities.

Remember that Rogoff and Reinhart show that when the ratio of debt to GDP rises above 90 percent, there seems to be a reduction of about 1 percent in GDP. The authors of this paper, and others, suggest that this might come from the cost of the public debt crowding out productive private investment.

Think about that for a moment. We are on an almost certain path to a debt level of 100 percent of GDP in just a few years, especially if you include state and local debt. If trend growth has been a yearly rise of 3.5 percent in GDP, then we are reducing that growth to 2.5 percent at best. And 2.5 percent trend GDP growth will not get us back to full employment. We are locking in high unemployment for a very long time, and just when some 1 million people will soon be falling off the extended unemployment compensation rolls.

Government transfer payments of some type now make up more than 20 percent of all household income. That is set up to fall rather significantly over the year ahead unless unemployment payments are extended beyond the current 99 weeks. There seems to be little desire in Congress for such a measure. That will be a significant headwind to consumer spending.

Government debt-to-GDP for Britain will double from 47 percent in 2007 to 94 percent in 2011 and rise 10 percent a year unless serious fiscal measures are taken. Greece’s level will swell from 104 percent to 130 percent, so the United States and Britain are working hard to catch up to Greece, a dubious race indeed. Spain is set to rise from 42 percent to 74 percent and only 5 percent a year thereafter, but their economy is in recession, so GDP is shrinking and unemployment is 20 percent. Portugal? In the next two years, 71 percent to 97 percent, and there is almost no way Portugal can grow its way out of its problems. These increases assume that we accept the data provided in government projections. Recent history argues that these projections may prove conservative.

Japan will end 2011 with a debt ratio of 204 percent and growing by 9 percent a year. They are taking almost all the savings of the country into government bonds, crowding out productive private capital. Reinhart and Rogoff, with whom you should by now be familiar, note that three years after a typical banking crisis, the absolute level of public debt is 86 percent higher, but in many cases of severe crisis, the debt could grow by as much as 300 percent. Ireland has more than tripled its debt in just five years.

The BIS paper continues:

We doubt that the current crisis will be typical in its impact on deficits and debt. The reason is that, in many countries, employment and growth are unlikely to return to their pre-crisis levels in the foreseeable future. As a result, unemployment and other benefits will need to be paid for several years, and high levels of public investment might also have to be maintained.

The permanent loss of potential output caused by the crisis also means that government revenues may have to be permanently lower in many countries. Between 2007 and 2009, the ratio of government revenue to GDP fell by 2–4 percentage points in Ireland, Spain, the United States, and the United Kingdom. It is difficult to know how much of this will be reversed as the recovery progresses. Experience tells us that the longer households and firms are unemployed and underemployed, as well as the longer they are cut off from credit markets, the bigger the shadow economy becomes.

Clearly, we are looking at a watershed event in public spending in the United States, United Kingdom, and Europe. Because of the Great Financial Crisis, the usual benefit of a sharp rebound in cyclical tax receipts will not happen. It will take much longer to achieve any economic growth that could fill the public coffers.

Now, let’s skip a few sections and jump to the heart of their debt projections.

The Future Public Debt Trajectory

There was some discussion whether we should summarize the following section or use the actual quotation. We opted to use the quotation, as the language from the normally conservative BIS is most graphic. We want the reader to understand their concerns in a direct manner. This is in many ways the heart of the crisis that is leading the developed countries to endgame. It is startling to compare this with the seeming complacency of so many of our leading political figures all over the world.

We now turn to a set of 30-year projections for the path of the debt/GDP ratio in a dozen major industrial economies (Austria, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, the United Kingdom, and the United States). We choose a 30-year horizon with a view to capturing the large unfunded liabilities stemming from future age-related expenditure without making overly strong assumptions about the future path of fiscal policy (which is unlikely to be constant). In our baseline case, we assume that government total revenue and non-age-related primary spending remain a constant percentage of GDP at the 2011 level as projected by the OECD. Using the CBO and European Commission projections for age-related spending, we then proceed to generate a path for total primary government spending and the primary balance over the next 30 years. Throughout the projection period, the real interest rate that determines the cost of funding is assumed to remain constant at its 1998–2007 average, and potential real GDP growth is set to the OECD-estimated post-crisis rate.

Here, we feel a need to distinguish here for the reader the difference between real GDP and nominal GDP. Nominal GDP is the numeric vale of GDP, say, $103. If inflation is 3 percent, then real GDP would be $100. Often governments try to create inflation to flatter growth. This leads to higher prices and salaries, but they are not real; they are merely inflationary. That is why economists always look at real GDP, not nominal GDP. Reality is slightly more complicated, but that is the general idea. That makes these estimates quite conservative, as growth-rate estimates by the OECD are well on the optimistic side. If they used less optimistic projections and factored in the current euro crisis (it is our bet that when you read this in 2011, there will still be a euro crisis, and that it may be worse) and potential recessions in the coming decades (there are always recessions that never get factored into these types of projections), the numbers would be far worse. Now, back to the paper.

As noted previously, this text is important to the overall intent.

From this exercise, we are able to come to a number of conclusions. First, in our baseline scenario, conventionally computed deficits will rise precipitously. Unless the stance of fiscal policy changes, or age-related spending is cut, by 2020 the primary deficit/GDP ratio will rise to 13% in Ireland; 8–10% in Japan, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States; [Wow! Note that they are not assuming that these issues magically go away in the United States as the current administration does using assumptions about future laws that are not realistic.] and 3–7% in Austria, Germany, Greece, the Netherlands and Portugal. Only in Italy do these policy settings keep the primary deficits relatively well contained—a consequence of the fact that the country entered the crisis with a nearly balanced budget and did not implement any real stimulus over the past several years.

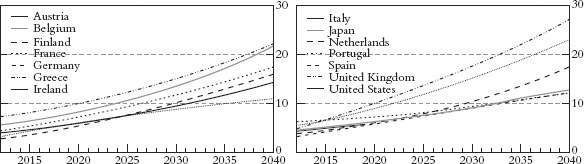

But the main point of this exercise is the impact that this will have on debt. The results [in Figure 6.1] show that, in the baseline scenario, debt/GDP ratios rise rapidly in the next decade, exceeding 300% of GDP in Japan; 200% in the United Kingdom; and 150% in Belgium, France, Ireland, Greece, Italy and the United States. And, as is clear from the slope of the line, without a change in policy, the path is unstable. This is confirmed by the projected interest rate paths, again in our baseline scenario. [Figure 6.1] shows the fraction absorbed by interest payments in each of these countries. From around 5% today, these numbers rise to over 10% in all cases, and as high as 27% in the United Kingdom.

Seeing that the status quo is untenable, countries are embarking on fiscal consolidation plans. In the United States, the aim is to bring the total federal budget deficit down from 11% to 4% of GDP by 2015. In the United Kingdom, the consolidation plan envisages reducing budget deficits by 1.3 percentage points of GDP each year from 2010 to 2013 (see e.g. OECD (2009a)).

To examine the long-run implications of a gradual fiscal adjustment similar to the ones being proposed, we project the debt ratio assuming that the primary balance improves by 1 percentage point of GDP in each year for five years starting in 2012. The results are presented in [Figure 6.1]. Although such an adjustment path would slow the rate of debt accumulation compared with our baseline scenario, it would leave several major industrial economies with substantial debt ratios in the next decade.

This suggests that consolidations along the lines currently being discussed will not be sufficient to ensure that debt levels remain within reasonable bounds over the next several decades.

An alternative to traditional spending cuts and revenue increases is to change the promises that are as yet unmet. Here, that means embarking on the politically treacherous task of cutting future age-related liabilities. With this possibility in mind, we construct a third scenario that combines gradual fiscal improvement with a freezing of age-related spending-to-GDP at the projected level for 2011. [Figure 6.1] shows the consequences of this draconian policy. Given its severity, the result is no surprise: what was a rising debt/GDP ratio reverses course and starts heading down in Austria, Germany and the Netherlands. In several others, the policy yields a significant slowdown in debt accumulation. Interestingly, in France, Ireland, the United Kingdom and the United States, even this policy is not sufficient to bring rising debt under control.

And yet, many countries, including the United States, will have to contemplate something along these lines. We simply cannot fund entitlement growth at expected levels. Note that in the United States, even by draconian cost-cutting estimates, debt-to-GDP still grows to 200 percent in 30 years. That shows you just how out of whack our entitlement programs are, and we have no prospect of reform in sight. It also means that if we—the United States—decide as a matter of national policy that we do indeed want these entitlements, it will most likely mean a substantial value added tax, as we will need vast sums to cover the costs, but with that will lead to even slower growth.

Long before interest costs rise even to 10 percent of GDP in the early 2020s, the bond market will have rebelled. (See Figure 6.2.)This is a chart of things that cannot be. Therefore, we should be asking ourselves what is endgame if the fiscal deficits are not brought under control. Quoting again from the BIS paper:

Figure 6.2 Projected Interest Payments as a Percentage of GDP

Source: Bank for International Settlements, OECD, authors’ projections.

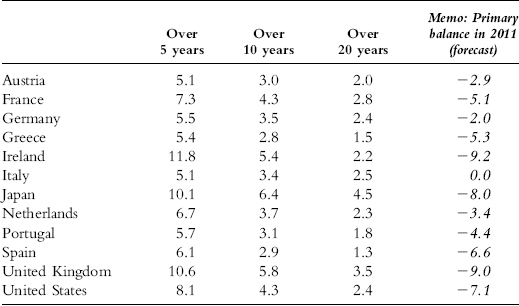

All of this leads us to ask: what level of primary balance would be required to bring the debt/GDP ratio in each country back to its pre-crisis, 2007 level? Granted that countries which started with low levels of debt may never need to come back to this point, the question is an interesting one nevertheless. [Table 6.1] presents the average primary surplus target required to bring debt ratios down to their 2007 levels over horizons of 5, 10 and 20 years. An aggressive adjustment path to achieve this objective within five years would mean generating an average annual primary surplus of 8–12% of GDP in the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom and Ireland, and 5–7% in a number of other countries. A preference for smoothing the adjustment over a longer horizon (say, 20 years) reduces the annual surplus target at the cost of leaving governments exposed to high debt ratios in the short to medium term.

Table 6.1 Average Primary Balance Required to Stabilize the Public Debt/GDP Ratio at 2007 Level (as percentage of GDP)1

Source: Bank for International Settlements, OECD, authors’ calculations.

Can you imagine the United States being able to run a budget surplus of even 2.4 percent of GDP? More than $350 billion a year? That would be a swing in the budget of almost 12 percent of GDP.

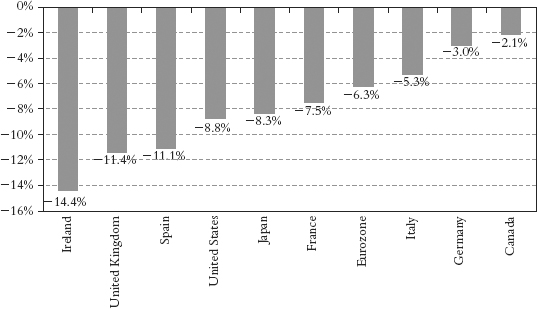

Now, we come to the section where they talk about the risks associated with the fiscal deficits. And by the way, we should note that 25 of 27 European countries are running deficits in excess of 3 percent of GDP. Ireland has a deficit of 14.3 percent. Portugal is at almost 10 percent. Greece is at almost 14 percent.

Look at the Figure 6.3 showing fiscal deficits. Notice that France is over 8 percent. The Eurozone as a whole is over 6 percent. Wow. We’ll look at the implications of this later.

Figure 6.3 Government Deficits/Surpluses as Percentage of GDP

Source: Bloomberg, Variant Perception.

The first risk is, of course, higher interest rates brought about by what the BIS authors term increased risk premia. In essence, investors want to get paid more for their increased risk. Interest on Greek debt for five-year bonds was 15 percent in May 2010. Now it is artificially propped up, but 10-year bonds are still yielding 10 percent. There is no way for the Greeks to grow their way out of the problem if interest rates are at 10 percent to 15 percent, up almost fourfold in less than a year. Rates are rising for other European peripheral countries as well. Ireland and Spain have seen their bonds rise whenever the European Central Bank hasn’t stepped in to help out.

[The second risk] associated with high levels of public debt comes from potentially lower long-term growth. A higher level of public debt implies that a larger share of society’s resources is permanently being spent servicing the debt. This means that a government intent on maintaining a given level of public services and transfers must raise taxes as debt increases. Taxes distort resource allocation, and can lead to lower levels of growth. Given the level of taxes in some countries, one has to wonder if further increases will actually raise revenue.

The distortionary impact of taxes is normally further compounded by the crowding-out of productive private capital. In a closed economy, a higher level of public debt will eventually absorb a larger share of national wealth, pushing up real interest rates and causing an offsetting fall in the stock of private capital.

This not only lowers the level of output but, since new capital is invariably more productive than old capital, a reduced rate of capital accumulation can also lead to a persistent slowdown in the rate of economic growth. In an open economy, international financial markets can moderate these effects so long as investors remain confident in a country’s ability to repay. But, even when private capital is not crowded out, larger borrowing from abroad means that domestic income is reduced by interest paid to foreigners, increasing the gap between GDP and GNP.

This squares solidly with the work done by Rogoff and Reinhart, showing that when the debt of a country reaches about 100 percent of GDP, there is a reduction in potential GDP growth of about 1 percent. As we wrote earlier, government debt and spending do not increase productivity. That takes private investment. And if government debt crowds out private investment, then there is lower growth, which is what the Rogoff and Reinhart study clearly shows.

And finally, the BIS authors note the risk that a government cannot run deficits in times of crisis to offset the effects of the crisis, if they already are running large deficits and have a large debt. In effect, fiscal policy is hamstrung.

The Challenge for Central Banks

Interestingly, the authors worry that one of the real problems central banks may face is that inflation expectations may become unanchored in the absence of a willingness on the part of the government to show fiscal constraint. Without some evidence of that willingness, monetary policy could lose any ability of being effective.

In other words, no matter how much the people at the Fed might like to help in a crisis, they may not be able to do anything effective if the U.S. government does not deal with its deficits. Again, from the BIS paper:

A second mechanism by which public debt can lead to inflation focuses on the political and economic pressures that a monetary policymaker may face to inflate away the real value of debt. The payoff to doing this rises the bigger the debt, the longer its average maturity, the larger the fraction denominated in domestic currency, and the bigger the fraction held by foreigners. Moreover, the incentives to tolerate temporarily high inflation rise if the tax and transfer system is mainly based on nominal cash flows and if policymakers see a social benefit to helping households and firms to reduce their leverage in real terms. It is, however, worth emphasizing that the costs of creating an unexpected inflation would almost surely be very high in the form of permanently high future real interest rates (and any other distortions caused by persistently higher inflation).

In John’s recent discussion with Richard Fisher, president of the Dallas Fed, he made it clear that the current leadership of the Fed knows it cannot excessively print money. So who is the BIS looking at when they talk about the temptation to inflate?

The Bank of England comes to mind, where inflation has surprised to the upside for the past two years (either the Bank of England is really bad at forecasting inflation, or they may not be too uncomfortable with it). Also Japan. And a number of smaller European central banks. Countries that would not mind their currencies falling, especially if the euro continues to slide. As the BIS notes, the temptation is going to be large. But there is no free lunch. Such things can spiral out of control and either end in tears or in someone like a Paul Volcker wrenching the economy into serious recession. We think the final sentence of the paragraph just quoted serves as a warning that such a policy dooms a country to even worse nightmares.

Now we come to the conclusion of the paper (again, all emphasis is ours):

Our examination of the future of public debt leads us to several important conclusions. First, fiscal problems confronting industrial economies are bigger than suggested by official debt figures that show the implications of the financial crisis and recession for fiscal balances. As frightening as it is to consider public debt increasing to more than 100% of GDP, an even greater danger arises from a rapidly ageing population. The related unfunded liabilities are large and growing, and should be a central part of today’s long-term fiscal planning.

It is essential that governments not be lulled into complacency by the ease with which they have financed their deficits thus far. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, the path of future output is likely to be permanently below where we thought it would be just several years ago. As a result, government revenues will be lower and expenditures higher, making consolidation even more difficult. But, unless action is taken to place fiscal policy on a sustainable footing, these costs could easily rise sharply and suddenly.

Second, large public debts have significant financial and real consequences. The recent sharp rise in risk premia on long-term bonds issued by several industrial countries suggests that markets no longer consider sovereign debt low-risk. The limited evidence we have suggests default risk premia move up with debt levels and down with the revenue share of GDP as well as the availability of private saving. Countries with a relatively weak fiscal system and a high degree of dependence on foreign investors to finance their deficits generally face larger spreads on their debts. This market differentiation is a positive feature of the financial system, but it could force governments with weak fiscal systems to return to fiscal rectitude sooner than they might like or hope.

Third, we note the risk that persistently high levels of public debt will drive down capital accumulation, productivity growth and long-term potential growth. Although we do not provide direct evidence of this, a recent study suggests that there may be non-linear effects of public debt on growth, with adverse output effects tending to rise as the debt/GDP ratio approaches the 100% limit (Reinhart and Rogoff (2009b)).

Finally, looming long-term fiscal imbalances pose significant risk to the prospects for future monetary stability. We describe two channels through which unstable debt dynamics could lead to higher inflation: direct debt monetization, and the temptation to reduce the real value of government debt through higher inflation. Given the current institutional setting of monetary policy, both risks are clearly limited, at least for now.

How to tackle these fiscal dangers without seriously jeopardizing the incipient recovery is the key challenge facing policymakers today. Although we do not offer advice on how to go about this, we believe that any fiscal consolidation plan should include credible measures to reduce future unfunded liabilities. Announcements of changes in these programs would allow authorities to wait until the recovery from the crisis is assured before reducing discretionary spending and improving the short-term fiscal position. An important aspect of measures to tackle future liabilities is that any potential adverse impact on today’s saving behavior be minimized. From this point of view, a decision to raise the retirement age appears a better measure than a future cut in benefits or an increase in taxes. Indeed, it may even lead to an increase in consumption (see, for example, Barrell et al. [2009] for an analysis applied to the United Kingdom).

The risk that no one talks about is the level of foreign investment in some of these countries and the consequent rollover risk. By this, we mean that when a bond comes due, you have to roll over that bond into another bond. If the party that bought the original bond wants cash to invest in something else or just does not want your bond risk anymore, you have to find someone to buy the new bond. Greece has a large number of bonds coming due soon. It is not just the new debt; they have to find someone to buy the old debt. And that is why they need so much money.

But it is not just a Greek problem. About 45 percent of Spain’s debt is owned by non-Spaniards, and they need to roll over old debt and new debt of 190 billion euros this year alone. That is bigger than the entire GDP of Portugal. Spain cannot finance this internally. But will foreigners buy 90 billion euros and, if so, at what price if they are not convinced that Spain will enact serious austerity measures?

Listen to European Central Bank Governing Council President Jean-Claude Trichet:

As regards fiscal policies, we call for decisive actions by governments to achieve a lasting and credible consolidation of public finances. The latest information shows that the correction of the large fiscal imbalances will, in general, require a stepping-up of current efforts. Fiscal consolidation will need to exceed substantially the annual structural adjustment of 0.5% of GDP set as a minimum requirement by the Stability and Growth Pact. . . .

The longer the fiscal correction is postponed, the greater the adjustment needs become and the higher the risk of reputational and confidence losses. Instead, the swift implementation of frontloaded and comprehensive consolidation plans, focusing on the expenditure side and combined with structural reforms, will strengthen public confidence in the capacity of governments to regain sustainability of public finances, reduce risk premium in interest rates and thus support sustainable growth.2

This is a man who wants some serious austerity. No garden-variety cuts here and there. And that brings us to the heart of the problem. The chart a few pages ago showed the large fiscal deficits involved. If those are tackled seriously, it will put many countries into outright recessions and reduce the growth in others. Some, like Greece, will be in what can only be called a depression.

The entire Eurozone is at serious risk of another recession if it has not already entered into a second phase as this book is published. And one country after another is going to have to convince foreigners to buy its debt. But if they make the cuts, their GDP will fall, ironically increasing their debt-to-GDP ratio and making investors demand even higher rates, which becomes a very vicious spiral.

Again, as Reinhart and Rogoff wrote: “Highly indebted governments, banks, or corporations can seem to be merrily rolling along for an extended period, when bang!—confidence collapses, lenders disappear, and a crisis hits.”3

Sovereign debt as an investment for banks was a good idea only a little while ago. Take cheap money, lever up, and make a nice spread. No longer is it such a good idea. Credit spreads are widening all over Europe. Interest rates are rising for the European periphery.

We once again find ourselves on a Minsky journey to a rather distressing Minsky moment. Hyman Minsky famously taught us that stability breeds instability. The more things stay the same, the more complacent we get, until Bang! We get the Minsky moment. We always seem to think this time is different, and it never is.

The Minsky journey is where investment goes from what Minsky called a hedge unit, where the investment is its own source of repayment; to a speculative unit, where the investment only pays the interest; to a Ponzi unit, where the only way to repay the debt is for the value of the investment to rise. The end of the journey is always the Minsky moment of violent markets and unwanted volatility.

We had that Minsky journey and Minsky moment in 2008, when the financial systems of the world collapsed. No one wanted U.S. mortgage debt, and every financial institution worried what was on the balance sheet of other banks. The interbank lending system froze.

Greece is now at its Ponzi moment of financing. As John Hussman pointed out, if interest rates are at 15 percent when you roll over debt, and your country is not growing, you have no way to actually service the debt. And thus, the Minsky moment when the markets walk away. Bang! From Hussman’s letter:

The basic problem is that Greece has insufficient economic growth, enormous [fiscal] deficits (nearly 14% of GDP), a heavy existing debt burden as a proportion of GDP (over 120%), accruing at high interest rates (about 8%), payable in a currency that it is unable to devalue. This creates a violation of what economists call the “transversality” or “no-Ponzi” condition. In order to credibly pay debt off, the debt has to have a well-defined present value (technically, the present value of the future debt should vanish if you look far enough into the future).

Without the transversality condition, the price of a security can be anything investors like. However arbitrary that price is, investors may be able to keep the asset on an upward path for some period of time, but the price will gradually bear less and less relation to the actual cash flows that will be delivered. At some point, the only reason to hold the asset will be the expectation of selling it to somebody else, even though it won’t be delivering enough payments to justify the price.

Unless Greece implements enormous fiscal austerity, its debt will grow faster than the rate that investors use to discount it back to present value. Moreover, to bail out Greece for anything more than a short period of time, the rules of the game would have to be changed to allow for much larger budget deficits than those originally agreed upon in the Maastricht Treaty.4

And if Greece has further problems, the market will look at Spain (and Portugal and Ireland). For Spain to continue to get financing, the market must believe they are going to make a credible effort at austerity measures. And because they need so much foreign financing, that moment may be sooner than we now think, as their rollover risk is massive. If Spain gets slapped, then who will be next?

There are examples of countries that have worked their way out of even worse problems and have done so without default. But those examples always came with currency devaluation and higher inflation. The Eurozone countries cannot devalue their currencies. The risk in Europe is that the austerity measures bring about deflation, which makes the debt an even greater burden.

The problem with having more liabilities than you can service means that someone has to take the loss. A report by Arnaud Marès at Morgan Stanley lays out the problem very well.

Debt/GDP ratios are too backward-looking and considerably underestimate the fiscal challenge faced by advanced economies’ governments. On the basis of current policies, most governments are deep in negative equity.

This means governments will impose a loss on some of their stakeholders, in our view. The question is not whether they will renege on their promises, but rather upon which of their promises they will renege, and what form this default will take.

So far during the Great Recession, sovereign (and bank) senior unsecured bond holders have been the only constituency fully protected from partaking in this loss.

It is overly optimistic to assume that this can continue forever. The conflict that opposes bond holders to other government stakeholders is more intense than ever, and their interests are no longer sufficiently well aligned with those of influential political constituencies.5

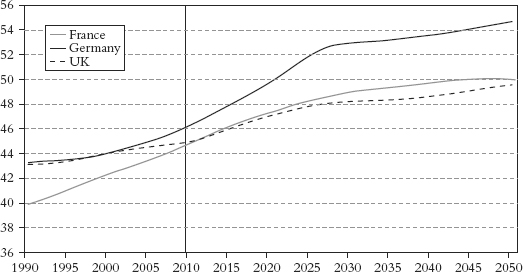

The author of this report highlights that most of the obligations countries now have is to their pensioners and senior citizens. Naturally, governments could cut Social Security or Medicare and reduce the future liability. There is no way that would fly politically. The complication is that as countries grow older, most of the voters also happen to be senior citizens. As Figure 6.4 from the report shows, in the United States and Europe, older voters will be the majority of voters in 2020. Politically, governments have very little time to make adjustments to retirement and medical benefits.

Figure 6.4 Age of the Median Voter

Note: Calculations assume stable turnout ratio for each age group, based on turnout at the most recent parliamentary election.

Source: UN, Bundeswahlleiter, INSEE, Ipsos-Mori, Morgan Stanley Research.

If governments can’t formally renege on their commitments and promises to seniors yet at the same time, they can’t reasonably pay back bondholders, what can they do? As Marès points out, there is a well-known pattern in government behavior called financial oppression:

There exists an alternative to outright default. “Financial oppression” (imposing on creditors real rates of return that are either negative or artificially low) has been used repeatedly in history in similar circumstances.

Investors should be prepared to face financial oppression, a credible threat against which current yields provide little protection.

Financial oppression has taken place in the past as an alternative to default in countries that are generally considered to have a spotless sovereign credit record. Examples include: the revocation of gold clauses in bond contracts by the Roosevelt administration in 1934; the experience by then Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton of issuing perpetual debt at an artificially low yield of 2.5% in the UK in 1946–47; and post-war inflationary episodes, notably in France (post both world wars), in the UK and in the US (post World War II). Each took place at a time when conflicting demands on finite government resources were high, and rentiers wielded reduced political power.6

Currently we’re beginning to see the financial oppression in developed countries. In the United States, the United Kingdom, and Europe, governments have forced their social security funds to only buy government bonds.

In the United States, for example, the Social Security dollars go to Treasury. Treasury issues so-called bonds against them. It would be incorrect to call these bonds because they’re really IOUs. Social Security gets a so-called bond, but they can’t sell it to anyone but the Treasury. A real bond can be marketed in the open market, but these securities issued to the Social Security Trust Fund are unmarketable and thus can only be redeemed at the U.S. Treasury. Even though the Treasury spends the Social Security money, it still counts these tax receipts against the federal deficit, masking the scale of the problems.

In Japan, government-controlled entities have been busy buying up Japanese government bonds (JGBs) for quite some time. The three largest holders of JGBs are Japan Post Bank, Japan Post Insurance, and Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF). However, there is a limit to how much these public piggybanks can be abused to buy public debt. Japan Post Insurance will soon not be a likely buyer because insurance reserves have been on a steady decline, given Japan’s demographics, and their year-over-year JGB holdings growth is almost 0 percent. At some stage, you run out of suckers to buy government debt.

What is certain is we will only see more efforts at financial oppression, but we will see increasing attempts to monetize deficits and reduce the future value of liabilities through inflation. It will not be pretty.