CHAPTER SEVEN

The Elements of Deflation

If Americans ever allow banks to control the issue of their currency, first by inflation and then by deflation, the banks will deprive the people of all property until their children will wake up homeless.

—Thomas Jefferson

Given the enormous levels of debt globally and the massive amount of government spending, one of the more important questions of the moment is whether we will face inflation or deflation. The quick answer is yes.

Without trying to be too facile, in most (developed) countries, there is the potential for both, so the trick is to figure out in what order they will come. For the next two chapters, we will look first at deflation and then at inflation (and hyperinflation!). We’ll explore what causes either economic event to happen.

The classic definition of deflation is a period of actual decline in the general price level and an economic environment that is characterized by inadequate or deficient aggregate demand.

The United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the European periphery are experiencing powerful, simultaneous deflationary forces that come from excessive debt and forced liquidation. This has created a classic balance sheet recession where after the bursting of a nationwide asset price bubble, a large number of private-sector balance sheets are left with more liabilities than assets. In response, central banks and fiscal authorities have launched equally massive increases the size of their balance sheet and increased spending to compensate for the private sector retrenchment. Even so, they have only managed to slow down the deleveraging and disinflation. But as we will see, that can change.

I (John) am a big fan of puzzles of all kinds, especially picture puzzles. I love to figure out how the pieces fit together and watch the picture emerge, and I have spent many an enjoyable hour at the table struggling to find the missing piece that helps make sense of the pattern.

Perhaps that explains my fascination with economics and investing, as there are no greater puzzles (except possibly the great theological conundrums or the mind of a woman, about either of which I have only a few clues).

The great problem with economic puzzles is that the shapes of the pieces can and will change as they try to fit in against one another. One often finds that fitting two pieces together changes the way they meld with the other pieces you thought were already nailed down, which may of course change the pieces with which they are adjoined, and suddenly your neat economic picture no longer looks anything like the real world.1

There are two types of major economic puzzle pieces.

The first are those pieces that represent trends that are inexorable: trends that will not themselves change, or if they do, it will be slowly, but they will force every puzzle piece that touches them to shift, due to the force of their power. Demographic shifts or technology improvements over the long run are examples of this type of puzzle piece.

The second type is what we can think of as balancing trends, or trends that are not inevitable but, if they come about, will have significant implications. If you place that piece into the puzzle, it, too, changes the shape of all the pieces of the puzzle around it. And in the economic supertrend puzzle, balancing trends can change the shape of other pieces in ways that are not clear.

Deflation and inflation are in the latter category. They change the way almost all other variables behave.

Deflation and inflation are two sides of a coin, making some people winners and others losers. There is no way around it. Moderate inflation can help borrowers and hurts creditors, while moderate deflation hurts borrowers and helps creditors. (High levels of inflation or deflation hurt everyone as no one wants to borrow or lend.) As inflation eats away at debt, it punishes both savers and lenders. When faced with deflation, however, people change the way they consume, save, invest, and live.

When you become a Federal Reserve Bank governor, you are taken into a back room and are given a DNA transplant that makes you viscerally and at all times opposed to deflation. Deflation is a major economic game changer.

There are two kinds of deflation: good deflation and bad deflation. Good deflation that comes from increased productivity is desirable. In the late 1800s, the United States went through an almost 30-year period of deflation that saw massive improvements in agriculture (such as the McCormick reaper) and the ability of producers to get their products to markets through railroads. In fact, too many railroads were built, and a number of the companies that built them collapsed. Just as we experienced with the fiber-optic cable build-out, there was soon too much railroad capacity, and freight prices fell. That was bad for the shareholders but good for consumers. It was a time of great economic growth.

We all understand good deflation intuitively since we have experienced that in the world of technology, where we view it as normal that the price of a computer will fall, even as its quality rises over time. Indeed, we would all be surprised if our iPads did not fall rapidly in price and show greatly improved quality over the next decade. That is a kind of deflation we can all live with. In fact, in a world of rising productivity in any industry, prices should fall.

Even the good deflationary period of the late 1800s was not without its troubles. Many farmers suffered tremendously with falling prices, and there was significant social unrest. Most of them bought their farms with loans and borrowed money to buy seeds and machinery. As we know, deflation helps lenders and hurts borrowers. Falling prices and fixed debts became a terrible combination for farmers. Unsurprisingly, because of deflation, during the last 30 years of the nineteenth century, money dominated politics, and candidates like William Jennings Bryan suggested more inflationary alternatives to a hard gold standard.

Bad deflation comes from a lack of pricing power and lower final demand. It hurts the incomes of both employer and employee and discourages entrepreneurs from increasing their production capacity and thus employment. This is what we saw in the Great Depression, when prices collapsed by 25 percent, and we’ve seen this in Japan after the bubble burst in 1989. Once the deflationary dynamic is started, people form deflationary expectations. They expect prices to keep going down. They realize that goods will fall in price, and it creates the incentive to postpone spending.

Most of us have grown up experiencing only inflation, and many of us have seen firsthand the problems of rampant inflation in the 1970s. The threat of deflation, therefore, may seem like a fantasy to most readers. But the risks of deflation are real and cannot be easily dismissed. Currently, unemployment is almost 10 percent in the United States (and quite high throughout much of Europe), which is almost twice its average of the past two decades, and capacity utilization is at very low levels. The economy has started turning up, but any double dip or a later recession could easily tip prices below 0 percent and start a deflationary dynamic where we all suffer from the elements of deflation.

If we have a double dip recession in 2011 or one soon thereafter when inflation is already low, there is a real chance we could get deflation, so let’s get familiar with it.

The Elements of Deflation: What Deflation Looks Like

Just as every schoolchild knows that water is formed by the two elements of hydrogen and oxygen in a very simple combination we all know as H2O, so bad deflation has its own elements of composition. Let’s look at some of them (in no particular order).

- Excess capacity and unemployment—First, deflation can happen because the real economy has tremendous slack and there is excess production capacity. It is hard to have pricing power when your competition also has more capacity than he wants, so he prices his product as low as he can to make a profit, but also to get the sale. The world is awash in excess capacity now. Eventually, we either grow the economy to utilize that capacity, or it will be taken off line through bankruptcy, a reduction in capacity (as when businesses lay off employees), or businesses simply exiting their industries. When the economy has excess slack, we see high and chronic unemployment. It reduces final demand, as people simply don’t have the money to buy things.

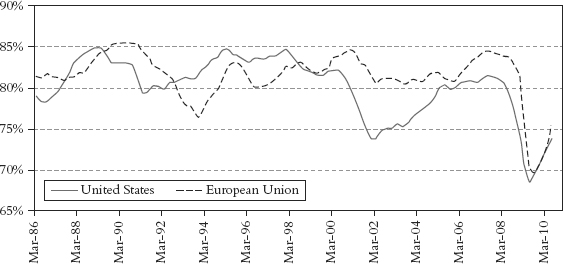

As Figure 7.1 shows, even after a strong bounce back from the lows following Lehman’s bankruptcy, we are still below troughs of previous recessions.

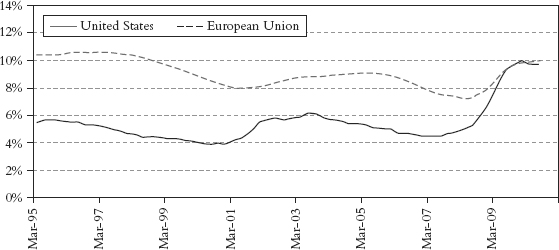

As Figure 7.2 shows, unemployment rates are near 10 percent in the United States and the European Union.

- Wealth effect in reverse—Deflation is also associated with massive wealth destruction. The events since the fall of 2007 have certainly provided that element. Home prices have dropped in many nations all over the world, with some exceptions like Canada and Australia (which may be in its own housing bubble!). Trillions of dollars of wealth has evaporated, no longer available for use. Likewise, the bear market in equities in the developed world has wiped out trillions of dollars in valuation, resulting in rising savings rates as consumers, especially those close to a wanted retirement, try to repair their leaking balance sheets.

And while increased saving is good for an individual, it calls into play Keynes’s paradox of thrift. That is, while it is good for one person to save, when everyone does it, it decreases consumer spending. Decreased consumer spending (or decreased final demand, in economic terms) means less pricing power for companies and is yet another element of deflation.

- Collapsing home prices—Falling home prices and a weak housing market are one more element of deflation. This is happening not just in the United States, but also much of Europe is suffering a real estate crisis. Japan has seen its real estate market fall almost 90 percent in nominal terms since 1989 in some cities, and that is part of the reason they have had 20 years with no job growth and that the nominal GDP is where it was 17 years ago.

- Deleveraging—Yet another element of deflation is the massive deleveraging that comes with a major credit crisis. Not only are consumers and businesses reducing their debt but also banks are reducing their lending. Bank losses (at the last count we saw) are more than $2 trillion and rising. Deflation can lead to default, bankruptcy and restructurings, and ultimately financial distress. Deflation also reduces the nominal value of collateral, reducing the creditworthiness of firms and forcing companies to sell assets into falling prices.

As an aside, the European bank stress tests were a joke. They assumed no sovereign debt default. Evidently, the thought of Greece not paying its debt was just not in the realm of their thinking. There were other deficiencies as well, but that is the most glaring. European banks are still a concern unless the European Central Bank (ECB) goes ahead and buys all that sovereign debt from the banks, getting it off their balance sheets.

Irving Fisher, the great classical economist, tells us that the definition of debt deflation is when everyone in a market tries to reduce debt, which results in distress selling. This leads to a contraction of the money supply as bank loans are paid off. This in turn leads to a fall in the level of asset prices and a still greater fall in the net worth of businesses, precipitating bankruptcies, a fall in profits, and a reduction in output, trade, and employment. This then leads to loss of confidence, hoarding of money, and a fall in nominal interest rates and a rise in deflation-adjusted interest rates. It becomes a self-reinforcing process. Deflation becomes a vicious circle.

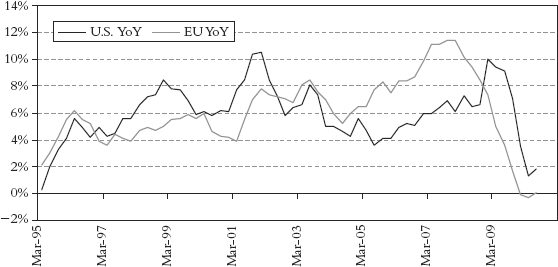

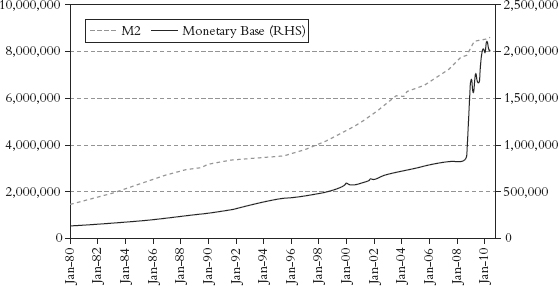

- Collapse of money and lending—When the money supply is falling in tandem with a slowing velocity of money, that brings up serious deflationary issues. And it is not just the United States. Global real broad money growth is close to zero (Figure 7.3). Deflationary pressures are the norm in the developed world (except for Britain, where inflation is the issue).

- Government austerity—In the short run, reducing government spending (in the United States at local, state, and federal levels) is deflationary, as noted in a previous chapter. Martin Wolf, in the Financial Times, wrote the following in July 2010 (arguing that the move to fiscal austerity is ill-advised):

We can see two huge threats in front of us. The first is the failure to recognize the strength of the deflationary pressures. . . . The danger that premature fiscal and monetary tightening will end up tipping the world economy back into recession is not small, even if the largest emerging countries should be well able to protect themselves. The second threat is failure to secure the medium-term structural shifts in fiscal positions, in management of the financial sector and in export-dependency, that are needed if a sustained and healthy global recovery is to occur.

We face the deflation of the depression era, and central bankers of the world are united in opposition. As Paul McCulley quipped this spring, when we asked him if he was concerned about inflation with all the stimulus and printing of money we were facing, “John, you better hope they can cause some inflation.” And he is right. If we don’t have a problem with inflation in the future, we are going to have far worse problems to deal with.

Saint Milton Friedman taught us that inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. A central bank, by printing too much money, can bring about inflation and destroy a currency, all things being equal. But that is the tricky part of that equation, because not all things are equal. The pieces of the puzzle can change shape. When the elements of deflation combine in the right order, the central bank can print what seems a boatload of money without bringing about inflation. And we may now be watching that combination in a number of countries.

As my friend Lacy Hunt of Hoisington Asset Management points out, Friedman did not consider any increase in the money supply to be inflationary at all times. He considered excessive money growth to be inflationary and insufficient money growth to be deflationary. For this reason, Friedman advocated the Fed be replaced by a monetary rule in which money growth was held at a stationary rate of increase that was just sufficient to cover increases in the labor force and productivity. It is also important to recognize that Friedman then translated excessive or insufficient money growth into inflation or deflation, because he believed the velocity of money to be stable. This was true during the period when Friedman conducted the bulk of his empirical work (i.e., from about 1950 to 1980). However, after 1980, the velocity of money rose rapidly, reaching a peak in 1997, which exceeded the prior peak in 1918.

What is the shape-shifting piece of the puzzle that Milton Friedman didn’t count on when he said inflation was a monetary phenomenon? The piece is the velocity of money. If you print money but it doesn’t go anywhere, you won’t get inflation.

We all know intuitively from experience that when too much money chases too few goods, prices go up. And if there is too little money, prices go down.

During World War II in prisoner-of-war camps, goods and treats came largely through Red Cross parcels. Parcels contained cookies, chocolate, sugar, jam, butter, and the like. They also included cigarettes, which back in those days almost everyone smoked without thinking about. People traded jam for chocolate or cigarettes for cookies.

It was a barter economy, and a tin of jam was worth half a pound of margarine, for example. A cigarette was worth a few pieces of chocolates. Bartering isn’t efficient, and the thing that was in highest supply and greatest demand was individual cigarettes. The cigarette started functioning as money; it became the unit of account and the medium of exchange (although it wasn’t a store of value, as people eventually smoked them!).

Whenever the Red Cross parcels arrived, the quantity of money in the camp increased. Naturally, prices rose whenever the Red Cross parcels arrived. If the quantity of cigarettes declined, prices in the camp fell. Sometimes Red Cross parcels were interrupted due to the vagaries of war, and that meant fewer cigarettes in the camp. As some of the cigarettes were used for smoking, fewer were available to trade, and prices of various goods and services declined; that is, deflation occurred.1

This is the standard quantity theory of money. If you increase the quantity of cigarettes (i.e., money), prices rise. If you reduce the quantity of cigarettes or money, prices fall. So far, so simple. But the one thing that complicates matters is velocity.

Let’s dig a little further and explore the concept of velocity of money. The velocity of money is the average frequency with which a unit of money is spent. For example, let’s assume a very small economy of just you and me, which has a money supply of $100. I have the $100 and spend it to buy $100 of flowers from you. You in turn spend $100 to buy books from me. We have created $200 of our gross domestic product from a money supply of just $100. If we do that transaction every month (12 × $200), we would have $2,400 of GDP from our $100 monetary base.

What that means is that gross domestic product is a function of not just the money supply but how fast the money supply moves through the economy. Stated as an equation, it is P = MV, where P is the price of your gross domestic product (nominal, so not inflation-adjusted here), M is the money supply, and V is the velocity of money.

Bear with us if this gets technical, but it’s important.

Now, let’s complicate our illustration just a bit, but not too much at first. This is very basic, and for those of you who will complain that we are being too simple, wait a few pages, please. Let’s assume an island economy with 10 businesses and a money supply of $1 million. If each business does approximately $100,000 of business a quarter, then the gross domestic product for the island would be $4 million (4 times the $1 million quarterly production). The velocity of money in that economy is 4.

But what if our businesses got more productive? We introduce all sorts of interesting financial instruments, banking, new production capacity, computers, technical innovations, and robotics, and now everyone is doing $100,000 per month. Now our GDP is $12 million and the velocity of money is 12. But we have not increased the money supply. We’re still trading with the same amount of money. Again, we assume that all businesses are static. They buy and sell the same amount every month. There are no winners and losers as of yet.

Now let’s complicate matters. Two of the kids of the owners of the businesses decide to go into business for themselves. Having learned from their parents, they immediately become successful and start doing $100,000 a month themselves. The GDP potentially goes to $14 million. For everyone to stay at the same level of gross income, the velocity of money must increase to 14.

Now, this is important. In all our examples, the amount of money has stayed the same. What has changed is the velocity. But what if the velocity of money doesn’t increase?

If the velocity of money does not increase, that means that each business is now going to buy and sell less in dollar terms each month. Remember, nominal GDP is money supply times velocity. If velocity does not increase, GDP will stay the same. The average business (there are now 12) goes from doing $1.2 million a year down to $1 million.

Each business now is doing around $80,000 per month. Overall, production is the same, but it is divided up among more businesses. For each of the businesses, it feels like a recession. They have fewer dollars, so they buy less and prices fall. This is a deflationary environment. In that world, the local central bank recognizes that the money supply needs to grow at some rate to make the demand for money neutral.

If the central bank of our island increases the money supply too much, you would have too much money chasing too few goods, and inflation would manifest its ugly head. (Remember, this is a very simplistic example. We assume static production from each business, running at full capacity.)

Let’s say the central bank overshoots the increase in production and doubles the money supply to $2 million. If the velocity of money is still 12, then the GDP would grow to $24 million. That would be a good thing, wouldn’t it?

No, because we only produce 20 percent more goods from the two new businesses. There is a relationship between production and price. Each business would now sell $200,000 per month or double their previous sales, which they would spend on goods and services, which only grew by 20 percent. They would start to bid up the price of the goods they want, and inflation sets in. Think of the 1970s.

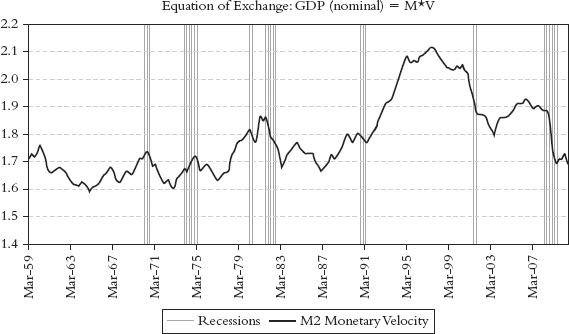

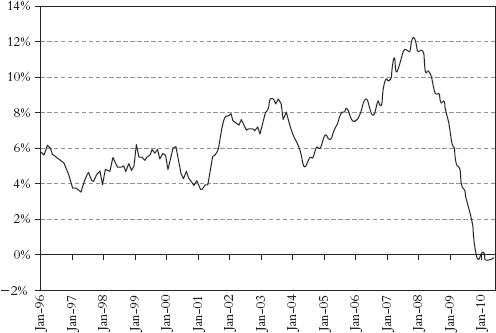

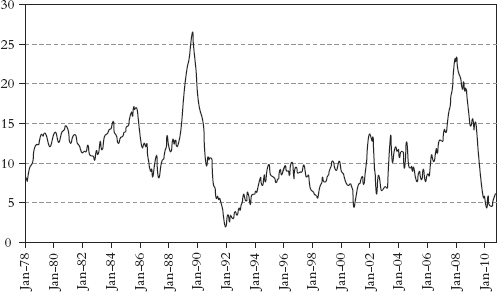

Now, what about the velocity of money? Nobel laureate Milton Friedman taught us that inflation was always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon. That is, if inflation shows up, then the central bank has been printing too much money. Friedman assumed the velocity of money was constant in his work. And it was from about 1950 until 1978, when he was doing his seminal work. But then things changed. Let’s look at two charts.

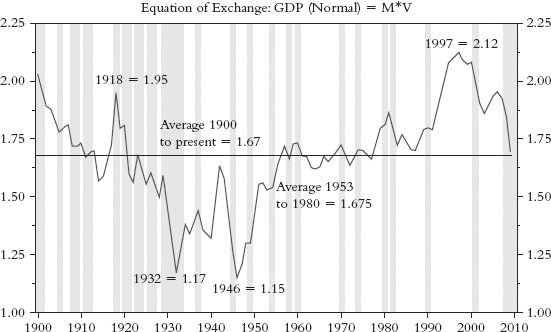

First, let’s look at Figure 7.4, which shows the velocity of money for the last 108 years. Notice that the velocity of money fell during the Great Depression. And from 1953 to 1980, the velocity of money was almost exactly the average for the last 100 years. Note that the velocity of money appears to be mean reverting over long periods of time. That means one would expect the velocity of money to rise or fall over time back to the mean or average.

Figure 7.4 Velocity of Money 1900–2009 (annually)

Note: Through 2008. 2009; V = GDP/M, GDP = 14.3 trillion, M2 = 8.4 trillion, V = 1.69.

Source: Hoisington Investment Management, Federal Reserve Board, Bureau of Economic Analysis, Bureau of the Census, Monetary Statistics of the United States.

Some would make the argument that we should use the mean from more modern times, since World War II, but even then, mean reversion would mean a slowing of the velocity of money (V), and mean reversion implies that V would go below (overcorrect) the mean. However you look at it, the clear implication is that V could drop if it mean reverts. In a few paragraphs, we will see why that is the case from a practical standpoint.

Now, let’s look at the same chart since 1959 but with shaded gray areas that show us the times the economy is in recession. You can see this in Figure 7.5 (with recessions shaded). Note that with one exception in the 1970s, velocity drops during a recession. What is the response of the Federal Reserve Bank? An offsetting increase in the money supply to try to overcome the effects of the business cycle and the recession. If velocity falls, then money supply must rise for nominal GDP to grow. The Fed attempts to jump-start the economy back into growth by increasing the money supply.

The assumption is that GDP is $14.5 trillion, M2 is $8.5 trillion, and therefore velocity is 1.7, down from almost 1.95 just a few years ago. If velocity reverts to or below the mean, it could easily drop 10 percent from here. We will explore why this could happen in a minute.

But let’s go back to our equation, P = MV. If velocity slows by 10 percent (which it well could), then money supply (M) would have to rise by 10 percent just to maintain a static economy. But that assumes you do not have 1 percent population growth, 2 percent (or thereabouts) productivity growth, and a target inflation of 2 percent, which means M (money supply) needs to grow about 5 percent a year even if V was constant. And that is not particularly stimulative, given that we are in a relatively slow growth economy.

Now, why is the velocity of money slowing down? Notice the real rise in velocity from 1990 through about 1997. Growth in M2 was falling during most of that period, yet the economy was growing. That means that velocity had to rise faster than normal. Why? Primarily because of the financial innovations introduced in the early 1990s, like securitizations and CDOs. It is financial innovation that spurs above-trend growth in velocity.

And now we are watching the great unwinding of financial innovations, as they went to excess and caused a credit crisis. In principle, a CDO or subprime asset–backed security should be a good thing. And in the beginning, they were. But then standards got loose, greed kicked in, and Wall Street began to game the system. End of game.

What drove velocity (financial innovation) to new highs is no longer part of the equation. We no longer have all sorts of fancy vehicles like ABCP programs, SIVs, CDOs, and CMBSs making money move around the economy faster. The absence of these financial innovations is slowing things down. If the money supply did not rise significantly to offset that slowdown in velocity, the economy would already be in a much deeper recession.

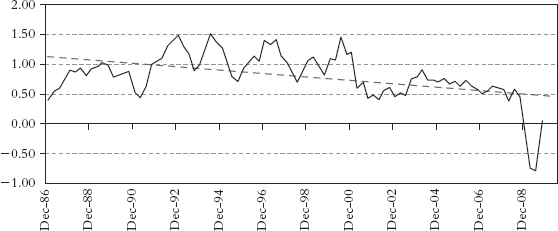

While the Fed does not have control over M2, when they lower interest rates, it is supposed to make us want to take on more risk, borrow money, and boost the economy. So, they have an indirect influence. And notice in Figure 7.6 that M2 has not been growing that much lately, after shooting up in late 2008 as the Fed flooded the market with liquidity.

Bottom line? Expect money-supply growth well north of what the economy could normally tolerate for the next few years. Is that enough? Too much? About right? We won’t know for a long time. This will allow armchair economists (and that is most of us) to sit back and Monday-morning quarterback for many years.

The concept of the velocity of money is something that drives the gold bugs nuts. A gold bug is someone for whom the answer to the question “Where should I invest?” is almost always gold, with a smattering of natural resources. They assume that fiat currencies (paper money) will go the way of all flesh, which is historically not an unrealistic assumption. The question is when, and the when can be a long way off, making gold a boring investment for long periods of time. Most gold bugs subscribe to the Austrian school of economics founded by Ludwig von Mises. Von Mises did not factor the velocity of money into his equations.

When gold bugs see a rise in the supply of money, they think that translates into a rise in the price of gold, as that should bring about inflation. And they would be right if monetary velocity remained constant.

If you assume a constant number of transactions, then the prices paid would be a direct function of the supply of money and velocity. But if velocity falls, you could have the supply of money rising, perhaps substantially, and prices paid actually falling if the velocity of money is falling faster than the rise in the money supply. As we said, this drives the gold bugs nuts.

As an aside, both your humble authors are believers in owning gold, and in some countries and currencies, owning more than a small insurance portfolio is well recommended. For us, gold is not so much an inflation hedge as a currency hedge. The odd fact is that in at least dollar terms, gold has not correlated all that well with inflation, although all the gold-oriented web sites and books seem to focus on gold as an inflation hedge. In fact, in the 1970s, the last real inflationary period we had, soy and lumber did better. But neither soy nor lumber is easy to buy or hold. People don’t tend to accumulate soybeans when they distrust their Zimbabwean dollars or German reichsmarks.

Gold is a very useful instrument when people lose confidence in a currency or in the central bank that controls that currency to maintain a reasonable purchasing power. Gold of late has gone up against the U.S. dollar, but it has gone up much more percentage-wise against the euro and the pound sterling.

Now, the central bank has some control over this process by controlling how much money they put into the system, by regulating how much actual reserves a bank must have, and by adjusting the price at which the central bank will make money available to the bank, plus a host of other factors. But in our simple world, we just need to know that an increase in lending will increase the money supply.

So, one way to think of the money supply is all of the cash plus all loans and credit available. (For the world, that is about $2 trillion in cash and $50 trillion in loans and credit.) And for the entire last 60-plus years, the amount of money supply, debt, and leverage in the system has been rising, steadily at first and then at a much faster pace. But now the shadow banking system has collapsed, and all the dynamics that kept debt going up have reversed gears.

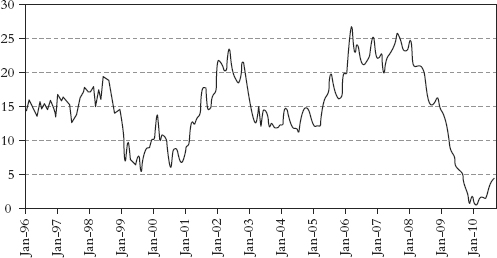

Notice in Figure 7.7 that a dollar of debt buys less and less GDP growth as time goes on, until debt has become a drag on the economy. Why? Go back to the chapter on Rogoff and Reinhart’s book. The increase in debt of late has been government debt, which is a drag on the economy. Government debt crowds out savings and investments.

Figure 7.7 Diminishing Marginal Productivity of Debt in the U.S. Economy (in $)

Source: Bloomberg, Variant Perception.

The Fed’s balance sheet may have doubled, but now the leverage in the system is shrinking. Individuals and businesses are paying down their debts and taking fewer loans. Banks are reducing their lending. This is a phenomenon all over the developed world. The governments are stepping in to take up some of the slack on the debt side, but there is a limit to how much even large governments can borrow, as we are finding out. Velocity falls when companies and individuals deleverage.

It is the end of the debt supercycle. It is endgame. As leverage and debt are taken off the table, there is real downward pressure on the money supply and the velocity of money. It is one of the most deflationary forces at work in the world today. Just look at the charts below of M3 money supply for various countries. It is turning negative, something not witnessed for a long time.

This is true for Europe, as you can see from Figure 7.8.

And for Australia, as you can see in Figure 7.9.

And even emerging markets like South Africa, as you can see in Figure 7.10.

The Roadmap Ahead: Bernanke’s Helicopter Speech

The current trend, as noted previously, is for lower inflation and falling velocity. That is why it will be important to watch the consumer price index (CPI) numbers even more closely in the coming months.

If the United States and/or Europe gets into outright deflation, we expect the respective central banks to react by increasing their asset purchases and by outright monetization of government debt, buying treasuries from insurance companies and pension funds. Putting more money into banks when they are not lending does not seem to be helpful as far as deflation is concerned. More mortgages? Corporate debt? Moving out the yield curve? All are options both the Fed and the ECB will consider. We need to be paying attention.

The good news is that we do have a road map of sorts. One of the most memorable scenes in the film Patton is when George C. Scott defeats the Germans and yells, “Rommel, you magnificent bastard! I read your book!” If an investor were to utter that today, they would have read the speech by Ben Bernanke. In November 2002, Bernanke gave a now-famous speech, which has come to be known as his helicopter speech, titled “Deflation: Making Sure ‘It’ Doesn’t Happen Here.”2 By the way, I (John) have always been convinced that his remark about printing presses and helicopters was a failed attempt at economist humor. This explains why we don’t get many offers from comedy clubs.

Let’s sum up the helicopter section: You can create inflation by printing a lot of money. But that is not the interesting part of the speech.

Let’s look at what Bernanke really said. First, he begins by telling us that he believes the likelihood of deflation is remote. But since it did happen in Japan and seems to be the cause of the current Japanese problems, we cannot dismiss the possibility outright. Therefore, we need to see what policies can be brought to bear on the problem.

He then goes on to say that the most important thing is to prevent deflation before it happens. He says that a central bank should allow for some “cushion” and should not target zero inflation, and he speculates that this is over 1 percent. Typically, central banks target inflation of 1 percent to 3 percent, although this means that in normal times inflation is more likely to rise above the acceptable target than fall below zero in poor times.

Central banks can usually influence this by raising and lowering interest rates. But what if the Fed funds rate falls to zero? Not to worry, there are still policy levers that can be pulled. Quoting Bernanke:

So what then might the Fed do if its target interest rate, the overnight federal funds rate, fell to zero? One relatively straightforward extension of current procedures would be to try to stimulate spending by lowering rates further out along the Treasury term structure—that is, rates on government bonds of longer maturities. . . .

A more direct method, which I personally prefer, would be for the Fed to begin announcing explicit ceilings for yields on longer-maturity Treasury debt (say, bonds maturing within the next two years). The Fed could enforce these interest-rate ceilings by committing to make unlimited purchases of securities up to two years from maturity at prices consistent with the targeted yields. If this program were successful, not only would yields on medium-term Treasury securities fall, but (because of links operating through expectations of future interest rates) yields on longer-term public and private debt (such as mortgages) would likely fall as well.

Lower rates over the maturity spectrum of public and private securities should strengthen aggregate demand in the usual ways and thus help to end deflation. Of course, if operating in relatively short-dated Treasury debt proved insufficient, the Fed could also attempt to cap yields of Treasury securities at still longer maturities, say three to six years.

He then proceeds to outline what could be done if the economy falls into outright deflation and uses the examples, and others, cited previously. It seems clear to me from the context that he is making an academic list of potential policies the Fed could pursue if outright deflation became a reality. He was not suggesting they be used, nor do we believe he thinks we will ever get to the place where they would be contemplated. He was simply pointing out that the Fed can fight deflation if it wants to. (And now, in late 2010, that question might become more than academic.)

With this as background, we can begin to look at what we believe is the true import of the speech. Read these sentences, noting our boldface words:

A central bank, either alone or in cooperation with other parts of the government, retains considerable power to expand aggregate demand and economic activity even when its accustomed policy rate is at zero.

The basic prescription for preventing deflation is therefore straightforward, at least in principle: Use monetary and fiscal policy as needed to support aggregate spending. . . . [As Keynesian as you can get.]

Some observers have concluded that when the central bank’s policy rate falls to zero—its practical minimum—monetary policy loses its ability to further stimulate aggregate demand and the economy.

To stimulate aggregate spending when short-term interest rates have reached zero, the Fed must expand the scale of its asset purchases or, possibly, expand the menu of assets that it buys.

Now, let us go to his conclusion:

Sustained deflation can be highly destructive to a modern economy and should be strongly resisted. Fortunately, for the foreseeable future, the chances of a serious deflation in the United States appear remote indeed, in large part because of our economy’s underlying strengths but also because of the determination of the Federal Reserve and other U.S. policymakers to act preemptively against deflationary pressures. Moreover, as I have discussed today, a variety of policy responses are available should deflation appear to be taking hold. Because some of these alternative policy tools are relatively less familiar, they may raise practical problems of implementation and of calibration of their likely economic effects. For this reason, as I have emphasized, prevention of deflation is preferable to cure. Nevertheless, I hope to have persuaded you that the Federal Reserve and other economic policymakers would be far from helpless in the face of deflation, even should the federal funds rate hit its zero bound.

And there you have it. All the data pointing to a slowing economy? It puts us (in the United States) closer to deflation. It is not the headline data per se we need to think about. We need to start thinking about what the Fed will do if we have a double-dip recession and start to fall into deflation. Will they move out the yield curve, as he suggested? Buy more and varied assets, like mortgages and corporate debt? What will that do to markets and investments?

Note that last bolded line: “For this reason, as I have emphasized, prevention of deflation is preferable to cure.” If Bernanke is true to his words, that means he may act in advance of the next recession if the data continue to come in weak and deflation starts to actually become a threat. That is the thing we don’t see in all the economic data—the potential for new Fed action. Let’s hope that, like the deflation scare in 2002, it doesn’t come about. Stay tuned.

If great contractions are caused by excessive debt and these contractions lead to deflation, then the Fed can only temporarily offset the inevitable deflation. Quantitative easing (QE) will only work by inducing another borrowing and lending cycle. This will mean that the economy will add more leverage to an already overleveraged economy. Thus, the QE buys the economy some additional growth but only for a limited time. Why limited? The additional leverage leads to economic deterioration and increased systemic risk. Thus, the only fundamental fix for an economy plagued by extreme overindebtedness is time and austerity. There is no lasting monetary policy fix.

One final thought before we close this chapter on deflation. Recessions are by definition deflationary. One of the things we learned from This Time Is Different by Rogoff and Reinhart is that economies are more fragile and volatile and that recessions are more frequent after a credit crisis. Further, spending cuts are better than tax increases at improving the health of an economy after a credit crisis.

We think we can take it as a given that there is another recession in front of the United States and/or Europe at some point. That is the natural order of things. But it would be better to have that inevitable recession as far into the future as possible, and preferably with a little inflationary cushion and some room for active policy responses. A recession in 2011 or 2012 would be problematic, if not catastrophic. Rates are as low as they can go. Higher deficit spending, as a way to address recession, is not in the political cards without very serious consequences. Yet unemployment would shoot up and tax collections go down at all levels of government if there were another recession.

That is why we worry so much about taking the Bush tax cuts away when the economy is weak. When you read this, we will know what Congress did about them. Today, as we write, it is up in the air. Now, maybe those who argue that tax increases don’t matter are right. They have their academic studies. But the preponderance of work suggests those studies are flawed and at worst are guilty of data mining (looking for data that support your already-developed conclusions).

Professor Michael Boskin wrote in July in the Wall Street Journal: “The president does not say that economists agree that the high future taxes to finance the stimulus will hurt the economy. (The University of Chicago’s Harald Uhlig estimates $3.40 of lost output for every dollar of government spending.) Either the president is not being told of serious alternative viewpoints, or serious viewpoints are defined as only those that support his position. In either case, he is being ill-served by his staff.”

As we finalize this book, the Fed has announced that it will buy $600 billion in Treasury debt by June 2010 and reserves the right to buy more. The theories that Bernanke invoked in the speech are about to be tested in the reality of the world economy.

We are in a period when the Fed is in the process of reflating the economy, or at least attempting to do so. They will eventually be successful if they persist (though at what cost to the value of the dollar, one can only guess). One can have a theoretical argument about whether that is the right thing to do (we are most vocal that it isn’t!) or whether the Fed should just leave things alone, let the banks fail, and let the system purge itself. We find that a boring and almost pointless argument.

The people in control don’t buy Austrian economics. It makes for nice polemics but is never going to be policy. We are much more interested in learning what the Fed and Congress will actually do and then shaping our portfolio accordingly. (And the same goes if you live in Europe or Britain or Japan!)

A mentor of mine once told me that the market would do whatever it could to cause the most pain to the most people. One way to do that would be to allow deflation to develop over the next few quarters or years, thereby probably affecting many investment classes, before inflation and then stagflation become (hopefully) the end of our perilous journey. Which, of course, would be good for gold. If you can hold on in the meantime.

Is it possible that we can find some Goldilocks end to this crisis? That the Fed can find the right mix, and Congress wakes up and puts some fiscal adults in control? All things are possible, but that is not the way we would bet.

While there are some who are very sure of our near future, we are not. There are just too many variables. Let us give you one scenario that worries us. Congress shows no discipline and lets the budget run through a few more trillion in the next two years. The Fed has been successful in reflating the economy after it has embarked on even more aggressive quantitative easing. The bond markets get very nervous, and longer-term rates start to rise. What little recovery we are seeing is threatened by higher rates in a period of high unemployment.

Does the Fed monetize the debt and bring on real inflation and further destruction of the dollar? Or allow interest rates to rise and once again push us into recession? (A triple dip?) The Fed is faced with a dual mandate, unlike other central banks. They are supposed to maintain price equilibrium and also set policy that will encourage full employment. At that point, they will have to choose one over the other. There are no good choices.

1This explains why all of the mathematical models make assumptions about variables that allow the models to work, except that what they end up showing is not related to the real world, which is composed of dynamic and not static variables.