CHAPTER NINE

The United States

The Mess We Find Ourselves In

We are hurtling irreversibly toward a budgetary crack-up that will generate the mother of all crises in global bond and currency markets.

—David Stockman, director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Ronald Reagan

Something that can’t go on, will stop.

—Herb Stein, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Richard Nixon

When we started writing this book, we purposefully set out to write so simply that even a politician could understand the nature of our problems. If there is any chapter in this book that is specifically written for congressmen, it is this chapter. We hope they will read it. We hope it will add something positive to the national conversation.

After the collapse of Lehman Brothers and AIG, almost all Americans hated Wall Street, yet surprisingly, one institution in America had a lower poll rating. No points for guessing. It is too easy.

Congress is the most reviled institution in America and with reason. According to a report by the Pew Center for People and the Press, “When asked for a single word that best describes their impression of Congress, ‘dysfunctional,’ ‘corrupt,’ ‘self-serving’ and ‘inept’ are volunteered most frequently. Of people offering a one-word description, 86% have something negative to say, while only 4% say something positive. Just 12% believe that Republicans and Democrats are working together in dealing with important issues facing the country—81% don’t think so.”1 (Interestingly, when you poll people about their representative, the numbers are much higher. Evidently, it is the idiots from the other districts they do not like. So for the representatives reading this chapter, it is all those other guys and not you. Your constituents love you.)

Why is it that Congress is so looked down on? As this chapter will show, Congress, along with successive presidents, have done nothing to resolve long-term problems that will haunt us in years to come. Everyone knows we are on an unsustainable path of spending, yet not enough politicians have the foresight, let alone the courage, to do anything about it, with some notable exceptions.

Unfortunately, the debate in Washington is partisan and poisoned. Any serious effort at fiscal reform goes nowhere, and every congressperson is in favor in principle of reducing spending and curtailing entitlements, but few are willing to do so in practice.

Putting politics aside, in this chapter, we’ll look at the evidence from nonpartisan, independent analysts about the ruinous road ahead if we do not do something to reform ourselves. The verdict is unanimous. Many nonpartisan, independent studies and reports have highlighted the pathetic state the United States finds itself in. We’ll look at a few in this chapter to show how any sane person should recognize that the United States currently is like a car speeding 100 miles an hour heading toward a brick wall.

This is not a Republican issue, it is not a Democratic issue, and it is not even a Tea Party issue. It is an issue that concerns all of us. How we deal with our problems and what choices we make will determine what kind of Social Security we’ll get when we’re older, what kind of medical care we’ll receive, and how much we’ll be taxed. Unfortunately, we’ll probably get a lot less of what we want and we’ll pay a lot more.

In recent testimony before Congress, Chairman Bernanke pointed out the unsustainable fiscal situation the United States was in and the need to make difficult choices. He stated:

The recent projections from the Social Security and Medicare trustees show that, in the absence of programmatic changes, Social Security and Medicare outlays will together increase from about 8½ percent of GDP today to 10 percent by 2020 and 12½ percent by 2030. With the ratio of debt to GDP already elevated, we will not be able to continue borrowing indefinitely to meet these demands. Addressing the country’s fiscal problems will require a willingness to make difficult choices [Emphasis added]. In the end, the fundamental decision that the Congress, the Administration, and the American people must confront is how large a share of the nation’s economic resources to devote to federal government programs, including entitlement programs.2

In July 2010, the International Monetary Fund issued its annual review of U.S. economic policy. In language only a bureaucrat could write, “Directors welcomed the authorities’ commitment to fiscal stabilization, but noted that a larger than budgeted adjustment would be required to stabilize debt-to-GDP.”3 That is a smack-down in bureaucrat-speak.

If you read ahead, though, it gets much better. The IMF is really saying that the U.S. debt is much like Greece’s. In Section 6 of the July 2010 Selected Issues Paper, the IMF writes, “The U.S. fiscal gap associated with today’s federal fiscal policy is huge for plausible discount rates” [Emphasis added].

Translation: We’re pretty much bankrupt, and it is extremely unlikely we’ll be able to close the gap between what we collect and what we’ll spend. It adds that “closing the fiscal gap requires a permanent annual fiscal adjustment equal to about 14 percent of U.S. GDP.” Fourteen percent is huge. That is more than a trillion dollars to save a year to get our fiscal house in order.

The IMF isn’t the only one pointing out that we’re screwed (screwed is a technical economic term). In an earlier chapter, we quoted from the BIS report showing how most developed countries are on an unsustainable path. American observers recognize it as well. For example, the Committee on the Fiscal Future of the United States was established under the auspices of the National Academy of Sciences and the National Academy of Public Administration, supported by the MacArthur Foundation, to carry out a comprehensive study leading to a set of plausible scenarios for the federal budget, to put it on a path toward a stable fiscal future. The report is not a Republican or Tea Party or Democratic report. The committee that wrote it was staffed by experts of all political persuasions. As the document says:

Members of the committee have quite varied backgrounds and perspectives on the budget. We disagree on many policy matters; but we are unanimous that forceful, even painful, action must be taken soon to alter the nation’s fiscal course.

The federal government is currently spending far more than it collects in revenues, and if current policies are continued, will do so for the foreseeable future. Over the long term, three major programs—Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security—account for the projected faster growth in federal spending relative to revenues. No reasonably foreseeable rate of economic growth would overcome this structural deficit. . . .

The current trajectory of the federal budget cannot be sustained. Without a course change, the nation faces the risk of a disruptive fiscal crisis, a risk that increases each year that action to address the growing structural deficit is delayed [Emphasis added]. With delay, the available options become more extreme and therefore more difficult, and even more pain is shifted to future generations.

The cumulative effect of the fundamental mismatch between expected revenues and the spending implied by the federal government’s policies and commitments will be a very large and rapid increase in the amounts that the United States must borrow to finance current spending. This spending will include growing interest payments. . . . In addition to this fundamental imbalance, there has been a surge of spending and a drop in revenues because of the 2008–2009 economic downturn, which added more than $1.5 trillion of debt in just 1 year, about $4,500 of additional borrowing for each U.S. resident. This temporary borrowing surge is of concern, of course; however, it is the much larger longer term mismatch between projected spending and projected revenues implied by current policies that is the greater concern and the focus of this report.4

Failure to prepare for the future prevents us from taking steps today. For Keynesians who want greater fiscal spending and deficits in the short run to stimulate the economy, the irony is that if we actually got our fiscal house in order, we’d have greater flexibility to boost spending in a downturn. As Frederic Mishkin, a Columbia University professor and former U.S. Federal Reserve governor, has pointed out, if the United States took concrete steps to address future deficits right now, the government would have more freedom to run deficits in the short run if needed. As he wrote, “There really is a need for the Congress to get serious about long-run fiscal sustainability.”5

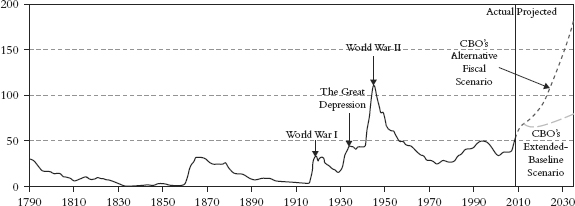

Another nonpartisan, independent analysis of our finances comes from the Congressional Budget Office, which is charged with studying bills that come before Congress. It paints a very dire picture. First, it shows what happens under a baseline scenario, which we’ll call the rosy scenario. It assumes everything goes well. You can see it in Figure 9.1.

Figure 9.1 Federal Debt Held by the Public 1790–2035 (percentage of GDP)

Source: Congressional Budget Office, The Long-Term Budget Outlook (June 2010) and Historical Data on Federal Debt Held by the Public (July 2010).

It also has an alternative fiscal scenario, which is much more plausible. As you can see, we become like Japan, with debt to GDP of 200 percent in 20 years.

The alternative scenario assumes the following: “Therefore, CBO also developed an alternative fiscal scenario, in which most of the tax cuts originally enacted in 2001 and 2003 are extended (rather than allowed to expire at the end of this year as scheduled under current law); the alternative minimum tax is indexed for inflation (halting its growing reach under current law); Medicare’s payments to physicians rise over time (which would not happen under current law); tax law evolves in the long run so that tax revenues remain at about 19 percent of GDP; and some other aspects of current law are adjusted in coming years.”

The potential problems of rising debt for the United States are hardly reassuring:

Beyond those gradual consequences, a growing level of federal debt would also increase the probability of a sudden fiscal crisis, during which investors would lose confidence in the government’s ability to manage its budget, and the government would thereby lose its ability to borrow at affordable rates. It is possible that interest rates would rise gradually as investors’ confidence declined, giving legislators advance warning of the worsening situation and sufficient time to make policy choices that could avert a crisis. But as other countries’ experiences show, it is also possible that investors would lose confidence abruptly and interest rates on government debt would rise sharply [Emphasis added]. The exact point at which such a crisis might occur for the United States is unknown, in part because the ratio of federal debt to GDP is climbing into unfamiliar territory and in part because the risk of a crisis is influenced by a number of other factors, including the government’s long-term budget outlook, its near-term borrowing needs, and the health of the economy. When fiscal crises do occur, they often happen during an economic downturn, which amplifies the difficulties of adjusting fiscal policy in response.6

The CBO points out something very important, and it relates to the sand piles and fingers of instability. Collapses happen suddenly and unexpectedly. They happen because of underlying instability, and they can be triggered by even small events.

My [John] good friend Niall Ferguson wrote about how unexpected and nonlinear collapses happen:

Imperial collapse may come much more suddenly than many historians imagine. A combination of fiscal deficits and military overstretch suggests that the United States may be the next empire on the precipice.

If empires are complex systems that sooner or later succumb to sudden and catastrophic malfunctions, rather than cycling sedately from Arcadia to Apogee to Armageddon, what are the implications for the United States today? First, debating the stages of decline may be a waste of time—it is a precipitous and unexpected fall that should most concern policymakers and citizens. Second, most imperial falls are associated with fiscal crises. All the above cases were marked by sharp imbalances between revenues and expenditures, as well as difficulties with financing public debt. Alarm bells should therefore be ringing very loudly, indeed, as the United States contemplates a deficit for 2009 of more than $1.4 trillion—about 11.2 percent of GDP, the biggest deficit in 60 years—and another for 2010 that will not be much smaller. Public debt, meanwhile, is set to more than double in the coming decade, from $5.8 trillion in 2008 to $14.3 trillion in 2019. Within the same timeframe, interest payments on that debt are forecast to leap from eight percent of federal revenues to 17 percent. . . .

These numbers are bad, but in the realm of political entities, the role of perception is just as crucial, if not more so. In imperial crises, it is not the material underpinnings of power that really matter but expectations about future power. The fiscal numbers cited above cannot erode U.S. strength on their own, but they can work to weaken a long-assumed faith in the United States’ ability to weather any crisis. For now, the world still expects the United States to muddle through, eventually confronting its problems when, as Churchill famously said, all the alternatives have been exhausted. Through this lens, past alarms about the deficit seem overblown, and 2080—when the U.S. debt may reach staggering proportions—seems a long way off, leaving plenty of time to plug the fiscal hole. But one day, a seemingly random piece of bad news—perhaps a negative report by a rating agency—will make the headlines during an otherwise quiet news cycle. Suddenly, it will be not just a few policy wonks who worry about the sustainability of U.S. fiscal policy but also the public at large, not to mention investors abroad. It is this shift that is crucial: a complex adaptive system is in big trouble when its component parts lose faith in its viability.7

When people suddenly and unexpectedly lose faith in U.S. debt, we will not see a slow increase in interest rates and a slow decline of the dollar. We will be unlikely to have time to take the right steps. By that stage, it will be too late. The decline will happen quickly and unexpectedly.

Congress: Blind, Ignorant, and Indifferent

You would think that the combined wisdom of the Congressional Budget Office, the Bank of International Settlements, the Committee on the Fiscal Future of the United States, and scores of other organizations would be enough for Congress to see how unsustainable our fiscal path is. And you’d be wrong. Perhaps some members of Congress read these reports. We know that some of them care. But the bottom line is that they collectively are doing nothing about it. Touching Social Security, Medicare, and health care is the political third rail. You will get elected only if you do not touch them. And because of that, we have no reform.

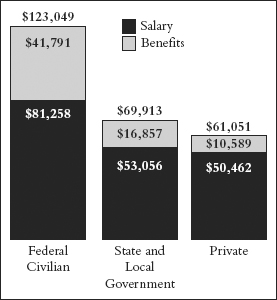

Congress displays little to no regard for even the slightest show of fiscal restraint. We can see this in how federal salaries have increased at a faster rate than salaries in the private sector, and we can see it in how quickly benefits have expanded for federal workers. While workers’ earnings have gone nowhere, federal employees’ average compensation has grown to more than double what private-sector workers earn (that is not a typo!). The total irresponsibility is not recent. For the last nine years, federal workers have been awarded bigger average pay and benefit increases than private employees. Because of the sustained increases, the compensation gap between federal and private workers has doubled in the past decade.

Federal civil servants earned average pay and benefits of $123,049 in 2009 while private workers made $61,051 in total compensation, according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis (Figure 9.2). The data are the latest available. The federal compensation advantage has grown from $30,415 in 2000 to $61,998 last year.8

Figure 9.2 Average Compensation in the United States (2009)

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis (Julie Snider, USA Today).

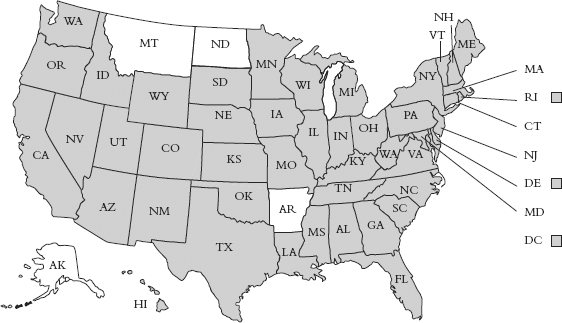

The fiscal problems in the United States are not purely confined to the federal government. At least 46 states had enormous troubles covering huge budget shortfalls for fiscal year 2011 (Figure 9.3). These came on top of the large shortfalls that 48 states faced in fiscal years 2009 and 2010.9

Figure 9.3 This Year 46 States Have Faced Budget Shortfalls

Note: Includes states with shortfalls in fiscal 2010.

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities survey (cbpp.org).

As Figure 9.4 shows, the budget shortfalls are gapingly large. Some states have shortfalls of 40 and 50 percent of their spending. If the states were countries, they would be prime candidates for bankruptcy or hyperinflation.

Figure 9.4 Total Shortfalls as Percentage of FY2011 Budget

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

Unfortunately, the very large budget shortfalls are not only due to the downturn. Before the Great Recession started, almost all states were running sizable budget deficits. Complacent financial markets let them do that. Things got much worse in the downturn, but things aren’t getting any better going forward.

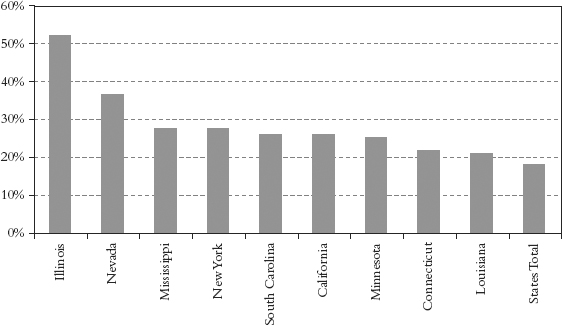

We don’t know what each state will pass as a budget in 2012, but we do have estimates for their shortfalls. As Figure 9.5 shows, Nevada and Illinois are going to have shortfalls of 40 percent going forward.

Figure 9.5 FY2012 Shortfall as Percentage of FY2011 Budget

Source: Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.

These insanely high budget shortfalls are simply not sustainable. Herb Stein, chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Richard Nixon, said, “Something that can’t go on, will stop.” One day completely out-of-control spending by state and local governments will come to an end. It is a matter of when, not if. That day of reckoning will probably come with a crisis.

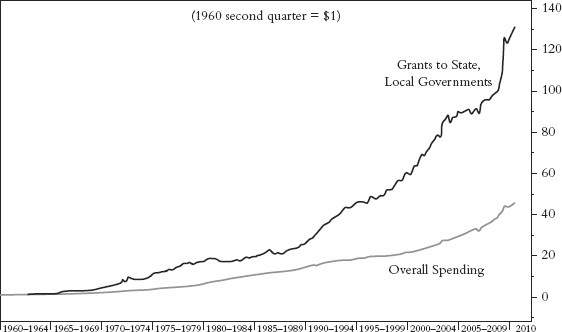

In the short run, crises have been postponed due to the federal government bailing out the states. Figure 9.6 shows the growth in federal payouts to state and local governments, also known as grants-in-aid.

Figure 9.6 Growth in Grants in Aid versus Total Spending

Source: Bloomberg Chart of the Day, Commerce Department.

According to Bloomberg News:

[Grants in aid] have increased almost three times as fast as overall spending during the period, according to data compiled by the Commerce Department. Funds were provided at a $525 billion annual rate in the second quarter, a 33 percent jump from two years ago. Most of the money went to pay health-care expenses under the Medicaid insurance program and to cover educational costs. . . .

The federal government provided $131.25 of state and local aid last quarter for every dollar spent 50 years ago. For total expenditures, the second-quarter figure was only $45.75. . . .10

To put this very simplistically, the states are like children who are vastly overspending, and daddy, that is, the federal government, is having to step in to bail them out. This cannot go on forever. At a certain stage, a good parent has to let the children suffer the consequences of their own actions. Actually, the parent really is you, the taxpayer, and other states. So the responsible states are bailing out the irresponsible states. And you, the taxpayer, will ultimately bail out your profligate government.

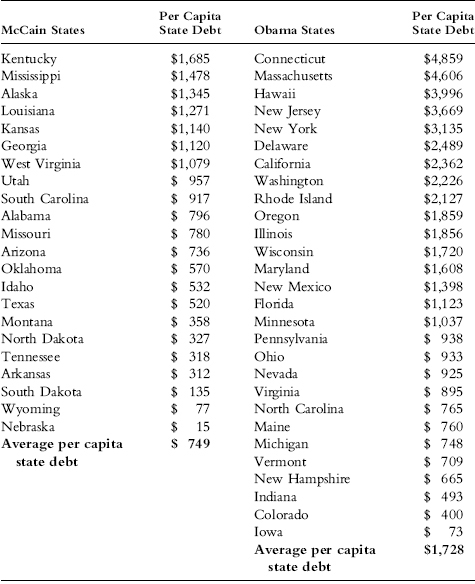

What is interesting is that this crisis is not evenly spread. In fact, it will be the fiscally conservative states and the fiscally conservative taxpayers who will bail out the fiscally profligate ones. Table 9.1 is extremely eye-opening. States where voters feel the government should do more for them end up with bigger debts. States that believe in smaller government typically have smaller debts. All the states that voted for McCain have very small debt/GDP while those that voted for Obama have very high debt/GDP.

Table 9.1 Per Capita Debt by State

Source: Marc Faber, Gloom Boom & Doom Report; Chuck Devore, Big Government, http://biggovernment.com.

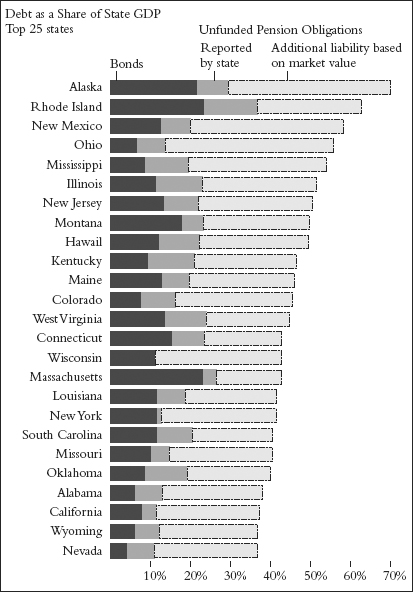

The problem is probably much bigger than the numbers suggest. Much like the United States, individual states have tremendous hidden liabilities. The total debt of California might look manageable at 8 percent of its economy. But if you include the fair value of the shortfall in California’s pension funds, the total liability jumps to 37 percent of its GDP.

We have earlier discussed the problems of Greece and the European periphery. Many U.S. states are in a terrible position, and if they were European countries, the fair value of their pension obligations would exceed the debt/GDP level of 60 percent as set out in the European Maastricht Treaty, according to Andrew Biggs, an economist with the American Enterprise Institute.

Some economists think the last straw for states and cities will be debt hidden in their pension obligations. As Figure 9.7 shows, even though pension obligations are not reported as debt on a state’s budget, the obligations are real, and when added to the existing debt, they show that the real burden states face is three to four times as large.

Figure 9.7 Overloaded with Unseen Debts

Note: While states’ explicit debts—the value of their bonds outstanding—may look manageable, those amounts do not include shortfalls in their pension funds. Currently, public pension funds are not required to disclose the market value of their pension obligations, though some say that is the more meaningful measure. States also share the burden of the national debt, which can further balloon a state’s total debt load. Source: © Andrew G. Biggs. Reprinted with permission of the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research, Washington, DC.

According to the New York Times, “Joshua Rauh, an economist at Northwestern University, and Robert Novy-Marx of the University of Chicago, recently recalculated the value of the 50 states’ pension obligations the way the bond markets value debt. They put the number at $5.17 trillion. After the $1.94 trillion set aside in state pension funds was subtracted, there was a gap of $3.23 trillion—more than three times the amount the states owe their bondholders.”11 This $3 trillion dollar number has been duplicated in two other studies using different methodology.

The United States has similar unstated liabilities. Our total debt is a little less than our GDP, but our long-term liabilities are much, much higher. As Professor of Economics Laurence Kotlikoff at Boston University has pointed out:

[The] gargantuan discrepancy between our “official” debt and our actual net indebtedness isn’t surprising. It reflects what economists call the labeling problem. Congress has been very careful over the years to label most of its liabilities “unofficial” to keep them off the books and far in the future. . . . The fiscal gap isn’t affected by fiscal labeling. It’s the only theoretically correct measure of our long-run fiscal condition because it considers all spending, no matter how labeled, and incorporates long-term and short-term policy.12

The official U.S. deficit and debt numbers are based on cash accounting, which tracks what comes into your checking account and what goes out. For the average person, that works fine for paying today’s bills, but it’s a poor way to measure a financial condition that could include credit card debt, car loans, a mortgage, and an overdue electric bill. Companies and complex institutions, for this reason, use accrual accounting, which does not judge how well you’re doing by your checking account. It measures income and expenses when they occur, or accrue. Accrual accounting gives a much more accurate picture of where your finances are.

The supreme irony is that federal law requires companies that have revenue of $1 million or more to use accrual accounting. If any private company used cash accounting instead of accrual accounting, its executives would be prosecuted by the government. It is illegal for businesses to keep their books the way the government does, hiding long-term obligations the way the government hides its indebtedness from voters.

One outcome that is extremely likely is that our taxes will go up. Some of these new taxes will be good. They’ll simply be reversing the ridiculous situation we currently find where special interests receive money from the government via subsidies. Other taxes, though, will be very poor for growth.

As Martin Feldstein has written:

Most federal nondefense spending, other than Social Security and Medicare, is now done through special tax rules rather than by direct cash outlays. . . . These tax rules—because they result in the loss of revenue that would otherwise be collected by the government—are equivalent to direct government expenditures. . . . This year tax expenditures will raise the federal deficit by about $1 trillion, according to estimates by the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation. If Congress is serious about cutting government spending, it has to go after many of them. . . .13

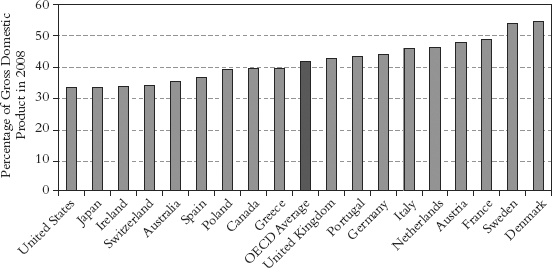

Indeed, the tax burden in the United States is actually low compared with other countries around the world. As Figure 9.8 shows, it is lower than almost every other major country.

Figure 9.8 Tax burden as Percentage of GDP in OECD

Source: “Choosing the Nation’s Fiscal Future,” Committee on the Fiscal Future of the United States, National Research Council and National Academy of Public Administration.

The United States has depended on foreigners to buy very large amounts of our debt. The largest buyers have been the Chinese, the Japanese, the Russians, and the Saudis. The Chinese and the Japanese recycle their dollars. We buy their products, and rather than selling the dollars we give them, they buy U.S. government bonds to keep the yuan and the yen from appreciating. The Saudis and the Russians do the same when we buy their oil. It’s an odd form of vendor financing.

Foreigners, however, are becoming less and less comfortable buying our bonds. They know that our fiscal situation is untenable. Here is a small episode that gives a real insight into what foreigners think about our debt.

The British daily newspaper the Telegraph reported on Tim Geithner’s first trip to China: “In his first official visit to China since becoming Treasury Secretary, Mr. Geithner told politicians and academics in Beijing that he still supports a strong US dollar, and insisted that the trillions of dollars of Chinese investments would not be unduly damaged by the economic crisis. Speaking at Peking University, Mr. Geithner said: ‘Chinese assets are very safe.’ The comment provoked loud laughter from the audience of students.”14 Even Chinese students know how unlikely any fiscal reform is in the United States.

In the words of David Stockman, director of the Office of Management and Budget under President Ronald Reagan:

A while back, when Tim Geithner told a group of Beijing students that Washington would get its fiscal house in order over the next five years, they guffawed. It is no wonder. The U.S. economy is comprised of an aging, debt-burdened population which manufactures little that is competitive in today’s over-capacitated global economy. In fact, we are down to 8 million manufacturing production jobs in an economy with 150 million workers. Such an economy must drastically cut spending and ramp-up savings and reinvestment to ever regain a healthy footing. That means public-sector savings in the form of budget surpluses, along with higher household savings rates than we have had for decades.15

Not long after Tim Geithner visited Beijing, a Chinese rating agency, Dagong Global Credit Rating Company, used its first entry into sovereign debt rating to paint a disturbing portrait of global sovereign creditworthiness, giving much greater weight to “wealth creating capacity” and foreign reserves than Fitch, Standard & Poor’s, or Moody’s. The United States falls to AA, while Britain and France slipped to AA−. Belgium, Spain, and Italy are ranked at A−, along with Malaysia. Table 9.2 shows that the United States is number 13 in the global ranking.

Table 9.2 Dagong Ratings

Source: Sovereign Credit Rating Report of 50 Countries in 2010, Dagong Credit Rating Company.

Let’s hear their rationale in slightly mangled English:

In the normal credit and debt relationship, the cash flow newly created by the debtor, rather than that newly borrowed, should be the fundamental of debt repayment, on the basis of which, the credit relation can exist and develop stably. The way of over-reliance on financing income and debt roll-over will ultimately lead to a strong reaction of bond market, thus when the borrowing costs and difficulties increase, the credit risks will burst dramatically.

Therefore, Dagong holds that the countries with current fiscal revenue sufficient to cover the debt service, have stronger fiscal strength than those countries which mainly depend on financing income to repay debts in the same circumstance, even sometimes the financing incomes of latter seem stable in the short term.16

Simply put, because U.S. debt is growing with no end in sight, we’re not paying down our debt. We simply roll it. We issue new debt to pay off the old and borrow a little more each time. As we have pointed out before, this violates the transversality or no-Ponzi condition. Without any meaningful fiscal reform, the only reason to hold a government bond is because someone else might pay more for it than you bought it for; that is, there might be a greater fool out there somewhere. The problem is that eventually markets run out of fools.

You will not be surprised to learn that Dagong International Credit Rating Company of China has been prohibited by the U.S. government from entering the U.S. market. Perhaps the reason is that the company is headquartered at Beijing without a branch in the United States and not involved in rating U.S.-based companies. It did not have any subscribers in the United States. The simpler explanation is that it is always easier to shoot the messenger than fix things.

As Reinhart and Rogoff have pointed out, when it comes to the various types of crises, there is very little difference between developed and emerging-market countries, especially as to the fallout. It seems that the developed world has no corner on special wisdom that would allow crises to be avoided or to be recovered from more quickly. In fact, because of their overconfidence—because they actually feel they have superior systems—developed countries can dig deeper holes for themselves than emerging markets. That is what is happening to the United States now. Our complacency is preventing us from making necessary fiscal adjustments. The United States has difficult choices ahead if we do not want to become like so many emerging-market countries that have faced debt and currency crises.

Again, when people have too much debt, they typically default. When countries have too much debt, you have one of three options:

1. They can inflate away the debt.

2. They can default on it.

3. They can devalue and hurt any foreigners who are holding the debt.

The Present Contains All Possible Futures

Let’s quickly review. Like teenagers, we as a U.S. polity have made a number of bad choices over the past decade. We allowed banks to overleverage and, in the case of AIG (and others), sell what were essentially naked call options of credit default swaps, based on their firm balance sheets, far in excess of their net worth, and that put our entire financial system at risk. We gave mortgages to people who could not pay them and did so in such large amounts that we again brought down the entire world financial system to the point that only with staggering amounts of taxpayer money was it brought back from the brink of Armageddon. We assumed that home prices were not in a bubble but were a permanent fixture of ever-rising value, and we borrowed against our homes to finance what seemed like the perfect lifestyle. We did not regulate the mortgage markets. We ran large and growing government deficits. We did not save enough. We allowed rating agencies to degrade their ratings to a point where they no longer meant anything. The list is much longer, but you get the idea.

Now, we are faced with a continuing crisis and the aftermath of multiple bubbles bursting. We are left with a massive government deficit and growing public debt, recent record unemployment, and consumers who are desperately trying to repair their balance sheets.

As we have seen in previous chapters, if present trends are left unchecked, we will need to find $15 trillion in the next 10 years, just to pay for U.S. government debt, without counting state, county, and city debt. And perhaps some loans for business will be needed? A few mortgages? Where can all this money come from? The answer is that it can’t be found. Long before we get to 2019, there will be an upheaval in the bond market, forcing what could be unpleasant changes.

We are left with no good choices, only difficult or bad ones. We have created a situation that is going to cause a lot of pain. It is not a question of pain or no pain; it is just when and how we decide (or are forced) to take it. There are no easy paths, but some bad choices are less bad than others. So, let’s review some of the choices we can make. (Again, we are being very general here.)

Argentinean Disease

One way to deal with the deficit is to do what Argentina and other countries have done: simply print the money needed to cover the deficits. Of course, that eventually means hyperinflation and the collapse of the currency and all debt. There are analysts who think this is an inevitable outcome. How else, they ask, can we deal with the debt? Where is the political willpower?

One large hedge-fund manager in Brazil humorously remarked that Argentina is a binomial country. When faced with two choices (hence binomial), they always made the bad choice. Could it happen here?

As we discussed earlier, hyperinflation is not an economic event; it is a political choice. The current political season is a sign that the voter population is beginning to pay attention to the need for something more than talk of change. There is growing discomfort with the size of the deficits. Further, the Fed would have to cooperate for there to be hyperinflation, and we think there is only a very slight (as in almost zero) chance of that happening. Could Congress change the rules and take over the Fed? Anything’s possible, but I seriously doubt there is any appetite in saner circles for such a thing to happen.

We think the chances of hyperinflation in the United States are quite low. Even given the recent bout of QE2, it is hard to conceive of the Fed actually monetizing the debt to allow the U.S. government to run large deficits, as opposed to the ostensible reason of fighting deflation. It would be the worst of all possible bad choices.

The Austrian Solution

Here I refer to the Austrian school of economic theory, based on the work of Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich Hayek. There are those in the Austrian camp who argue for the need to do away with the Fed; return to the gold standard; allow the banks that are now deemed too big to fail to go ahead and fail, along with any businesses that are also mismanaged (such as GM and Chrysler); and leave the high ground to new and more properly run businesses and banks.

In their model, government spending is slashed to the bone, as are (in most cases) taxes. The advantage is that, in theory, you get all your pain at once and then can begin to recover from what would be a very bad and deep recession. The bad news is that you risk getting 30 percent unemployment and another depression that could take a very long time to climb out of.

Now, let us say that we have greatly simplified their argument. If you want to learn more, you can go to www.mises.org. It is an excellent web site for all things Austrian. While I (John’s) am not Austrian, I have spent a lot of time reading the literature and have certain sympathies for this view.

That being said, this also has almost no chance of such a solution being implemented. In Congress, only my (John’s) friend Ron Paul is its advocate and now his son Rand in the Senate. Most Austrian followers are Libertarian by nature, and that is just not a political reality for the coming decade.

The Eastern European Solution

As it turned out, Niall Ferguson (author of the brilliant book The Ascent of Money and Harvard professor) was in Dallas last spring, and I (John) was graciously invited to hear him speak. He gave a great speech and signed books, and then we went to a local dive and proceeded to solve the world’s problems over scotch (Niall) and tequila (me), much further into the night than we originally intended. He’s a very funny and knowledgeable guy.

As we were talking about possible paths, he brought one to mind that I hadn’t thought of. He reminded me of the period after the fall of the Berlin Wall, as the nations of Eastern Europe broke from the former Soviet Union. They started with very weak economies and simply overhauled their entire governments and economies in a rather short period of time, though not in lockstep with one another. Privatization, lowered taxes, and the like were the order of the day.

We here in the United States are always talking about the need for reform. We need to reform health care or education or energy. In Eastern Europe, they did not reform in the sense that we use the word. In many cases, they simply started from scratch and built new systems. They had the advantage that there was general agreement that things did not work the way they had been, so there was more room for change.

Today in the United States, there are large constituencies that resist change. We only get to tinker around the edges, when real structural change is needed. Sadly, we agreed that here there is not much chance of major change. We can’t even get the obvious changes needed in the financial regulatory world.

Japanese Disease

In a few chapters, we will visit at length the problems facing Japan, but a quick tutorial is needed here. Their population is shrinking, as is their workforce. They are running massive fiscal deficits and have done so for almost 20 years. Government debt-to-GDP is now up to 200 percent and projected to rise to over 220 percent within a few years. They started their lost decades with a savings rate of almost 16 percent and are now down to 2 percent, as their aging population spends its savings in retirement. They have had no new job creation for 20 years, and nominal GDP is where it was 17 years ago.

As bad as our problems are here in the United States, their bubble was far more massive. Values of commercial property fell 87 percent! Their stock market is still down 70 percent 20 years later. They had twice as much bank leverage to GDP as the United States. (Think about how bad off we would be if bank lending was twice as large and had even worse defaults and capital shortfalls!)

And yet, they muddle through. Productivity has kept their standard of living very high. Up until recently, their exports were strong. The trading floors of the world are littered with the bodies of traders who have shorted Japanese government debt in the belief that it simply must implode. While we believe that it eventually will, if they stay on the path they are on, Japan is a very clear demonstration that things that don’t make sense can go on longer than we think.

Richard Koo (chief economist of Nomura Securities, in Tokyo) argues passionately that Japan had a balance sheet recession and that the only way for Japan to fight it was to run massive deficits. Banks were not lending and businesses were not borrowing, as both groups were trying to repair their balance sheets, which were savaged by the bursting of the bubble. It is said that at one time the value of the land on which the Emperor’s Palace sits in Tokyo was worth more than all of California. Clearly, this was a bubble that puts our housing bubble to shame.

We understand the point that there are differences between Japan and the United States. But there are also similarities. We, too, have had a balance sheet recession, although here it was mostly individuals and financial institutions that have had to retrench and repair their balance sheets.

Japan elected to run large deficits and raise taxes. A few chapters back, we covered the literature that suggests that government stimulus and deficits have no long-run positive effect on GDP.

Back in Chapter 3, we learned that if you increase government spending (the G in our equation), it will have a positive effect in the short run on GDP, but not in the long run. In essence, the increase in G must be made up by savings from consumers and businesses and foreigners.

But an increase in G does not enhance overall productivity. Government spending may be necessary, but it is not especially productive. You increase productivity when private businesses invest and create jobs and products. But if government soaks up the investment capital, there is less for private business.

And that is Japanese disease. You run large deficits, sucking the air out of the room, and you raise taxes, taking the money from productive businesses and reducing the ability of consumers to save. Then you go for 20 years with little or no economic or job growth.

This is the path we currently seem to be on. The Japanese experience says that it could last a lot longer than people think before we hit the wall because if savings rise in the United States, and if banks, instead of lending, put that money on deposit with the Fed, as they are now doing (to repair their balance sheets), the United States could run large deficits for longer than most observers (and we probably should include ourselves in that group) currently believe.

We will need 15 to 18 million new jobs in the next five years, just to get back to where we were only a few years ago. Without the creation of whole new industries, that is not going to happen. Nearly 20 percent of Americans are not paying anything close to the amount of taxes they paid a few years ago, and at least 10 million are now collecting some kind of unemployment benefits or welfare.

The jobs we need will not come from government transfer payments. As we saw earlier, they can only come from private businesses. And in reality, as we discussed in previous chapters, it is business start-ups that are needed, as that is where the real growth in net new jobs are. And that means investment. But if we allocate our investment money to government bonds, if we tax the capital needed by entrepreneurs who invest in and start businesses, we delay that return to growth.

Choosing large deficits does not reduce the amount of pain we will experience; it just seemingly reduces it in the short term and creates the potential for a serious economic upheaval when the bond market finally decides to opt for higher rates. This path is a bad choice, but sadly, in reality, it is one we could take without a serious move to curtail federal spending.

As we will see in a few chapters, Japan will soon be faced with its own Greek moment of truth. If we in the United States choose to continue to run large deficits, we will face that same end all too soon. It will mean high interest rates, ever larger deficits, worse unemployment, and a very diminished standard of living. This is not a wise choice.

The Glide Path Option

A glide path is the final path followed by an aircraft as it is landing. We need to establish a glide path to sustainable deficits—could we dream of surpluses? That is because at some point there will be recognition, either proactively or forced on us by the bond market, that large deficits are unsustainable in the long term.

If Congress and the president decided to lay out a real (and credible) plan to reduce the deficit over time, say five or six years, to where it was less than nominal GDP, the bond market would (we think) behave. Reducing deficits by $150 billion a year through a combination of cuts in growth and spending would get us there in five years.

The problem is that there is real temporary pain associated with this option. Remember that equation back in Chapter 3?

GDP (Gross Domestic Product) is defined as Consumption (C) plus Investment (I) plus Government Spending (G) plus [Exports (E) minus Imports (I)]

or:

GDP = C + I + G + (E ⁕ I)

Absent a growing private sector, if you reduce G (government spending), you also reduce GDP in the short run. You have to take some pain today to do that. But you avoid worse pain down the road: a bubble of massive federal debt that has to be serviced will be very painful when it blows up, as all bubbles do.

The glide path option means that structural unemployment is going to be higher than we like (which is actually the case with all the options). And the large tax increases that come with this option will by their very nature be a drag on growth. And of course, then we will eventually have to deal with the $70 trillion in our off-balance-sheet liabilities in Medicare and Social Security and pensions. We can debate tax increases all we want, but we sadly think we will soon have a VAT tax if we want to preserve some semblance of Medicare. And let’s be certain that an increase in taxes of the magnitude needed is not a pro-growth policy.

There are no easy or good options. Let’s just hope that we cut corporate taxes enough when we do create a VAT, that it will make our corporations more competitive on a global basis, which will be a boost for jobs.

That’s pretty much it. This is not a problem we can grow ourselves out of in the next few years. We have simply dug ourselves into a huge hole. This is not a normal recession. There is not a V ending to this recession. We are going to have to deal with the pain. It will be the pain of reduced returns on traditional stock market investments, eventually a lower dollar against most currencies (other than the euro, the pound, and the yen), low returns on bonds, European-like unemployment, lower corporate profits over the long term, and a very slow-growth environment. But if we choose this path, we will get through it in the fullness of time.

We can repair our national balance sheet. We can get deficits under control over time. We made it through the 1970s, which was not easy. There are whole new industries and technologies that promise an increase in jobs.

One last thought: Let’s assume that we find the political will to begin the process of creating some version of the glide path option, which we admit is not easy. That means the most important election in this whole process was not the one last November, nor will it be the one in 2012. Rather, it will be the one in 2014.

It is doubtful that unemployment will be back around 5 percent or that economic growth will be robust, if the future reveals itself to be somewhere on the line of the arguments we are making in this book. That is typically not a good atmosphere for incumbents. If voters react by demanding yet another round of stimulus and deficits from Congress, we will be training our politicians that we do not have the discipline to stay the course and will not allow them to make the hard choices.

Our leaders need to be candid with the American people. There are no magic answers, no easy solutions. The time for the blame game is over. We need to get on with the job of setting a course back to a sustainable economy that will grow and produce the jobs and opportunities that we have had in the past and we want for our children. It will mean some years of difficulty, but we can get through it if we choose to.

If we do not choose to act prudently, far more difficult times will be forced on us. Let’s hope we can be proactive.

It is beyond the scope of this book to suggest specific ideas on how we cut our spending or raise taxes. That we in the United States must get the fiscal deficit below nominal GDP and, even better, run a surplus is the case we have tried to make. The recent proposals by the chairmen of the President’s Commission on the Deficit were interesting. They are possibly a political nonstarter, but it is ideas like these that are going to be needed. To get to a reasonable deficit, there are going to have to be hard choices and real trade-offs.

In general, the heavy lifting should be done by spending cuts more than tax increases. As we saw from earlier chapters, tax increases have a growth cost, and it is growth that we need. And as we tinker with our tax code, let’s make sure we position our corporations to be more competitive. And for Pete’s sake, figure out a way to lower taxes on offshore income so that the corporations will bring it home and spend it here on job-creating business rather than investing it offshore.

Now, a few outside-the-box policy thoughts that might help.

Let’s Target Our Legal Immigration

We bring in about 1 million people a year from foreign countries, usually relatives of people already here. These are not typically people with degrees and money. Why not take a cue from Canada and think about letting in people with money and education for a few years?

Specifically, if you buy a house for cash and pay for health care two years in advance, you get a temporary green card. Keep your act together for four years, and you get to keep it. Let 250,000 people a year (and one or two of their family) come in and buy homes until we have gone through the excess inventory in homes, which would happen within a few years. It puts a floor in the housing market and gets the homebuilding businesses back to building a lot sooner, and that is a lot of jobs. That would seriously help get GDP back in the right direction.

Further, every one of those new immigrants is going to need to buy furniture, food, clothing, a car, and more. What a boost to the economy! And it helps support the dollar. If the average home purchase was $200,000, that would be $50 billion, with at least another $10 billion in other purchases, all of which has to be converted into dollars and is a direct stimulus to the economy. With not one penny in taxes, except that the new owners will, of course, pay taxes.

And these people are going to have to figure out how to make a living. Going on welfare gives up the right to the green card. So many of them will start small businesses (which hire people) or become part of the productive workforce.

Remember, this does not bring in any more people than we are already admitting; it just changes the component for a few years. And as we saw in Chapter 3, the only way you can grow your economy is to increase your population or increase your productivity. That’s it. We could do a lot better by choosing the people we want to come in by some metric other than simply being a relative. (We are not saying that we totally abandon that policy, just reduce the numbers in that program for a while.)

As a corollary to that concept, why not give every foreign graduate with an advanced degree a temporary green card, especially in the hard sciences? We train these people and then send them back to make their country more productive? We need them. Silicon Valley would still be a backwater if not for immigrants. Again, we need to give some thought to admitting immigrants who can help our return to a booming, productive economy.

There will be some high irony in a few years when not only the United States but also developed countries all over the world realize that they are competing on a worldwide stage for the best and brightest and that the real competition is to attract more of the best and brightest immigrants and keep more of their own people at home.

Getting Our Energy Policy Right

As we noted in a previous chapter, consumers and businesses can deleverage, the government can decide to run smaller deficits, and you can run large trade deficits, but you can only do two of them at any one time. (As we discussed, this is an accounting identity. It is not up for debate.). If we are serious about wanting to get our fiscal deficit under control, we must deal with our trade deficit. And that means getting real about our energy dependence on foreign oil. Short of making Alberta the 51st state, it will require some real changes.

We imported (on a net basis) $204 billion in petroleum-related products, which is well over half of our 2009 trade deficit of $380 billion, which itself was down from almost $700 billion in 2008.

Many economists (including us) speak of rising oil prices as a tax on the U.S. consumer, as it takes discretionary dollars that could be used for other goods and services and instead send them overseas. What if we could take that tax and spend it here in the United States on things we need?

As we said earlier in the book, we suggest a $0.30 a gallon gas tax increase every year until we are no longer dependent on foreign oil (phased in at 2.5 cents a month). If we start to become a net energy exporter, the tax would go back down. As in Europe, people would begin to opt for smaller, more fuel-efficient cars. A national miles per gallon that looked like Europe would get us a long way toward oil independence, if not all the way there.

We use about 140 billion gallons of gasoline a year in the United States, or about 72 percent of our total petroleum consumption. That would create a tax revenue stream of about $40 billion the first year, $80 billion the second year, and so on. That’s a lot of money.

We would not put that tax money back into federal coffers. We suggest using the entire tax for rebuilding our infrastructure, which is deteriorating badly. Bridges, roads, water systems, smart electric grids, self-sustaining public transportation (no subsidies!), and so on. The large bulk of the money should stay local where the taxes are paid, with a much lesser amount for national projects.

For what it is worth, those projects will create a lot of jobs, and this is a tax that will benefit our kids as they can use the improved infrastructure.

Let’s be clear. This is really a tax shift. By changing consumer preferences, and this will, we are taking money we are sending to oil-exporting nations and putting it to use here.

Next we would take a page from T. Boone Pickens and convert our national truck fleet to natural gas, a fuel we have in abundance. We could take some of the money from the gasoline tax to step in and build the needed infrastructure, but then it could be leased to operators and pay for itself over time.

As U.S. gas consumption slowed, it would have the benefit of reducing oil prices relative to what they would have been. It helps us in our fight to control the fiscal deficit and reduce our dependence on foreign energy.

And since we will eventually be shifting to an electric car fleet in the 2020s, we need to think about how we are going to create that electricity. While coal can certainly do the job, a much cleaner and more efficient way is modern nuclear power. We need to build (pick a number) 50, 75, or 100 nuclear power plants as we build a smart grid that reduces our dependence on fossil fuels.

Getting the Right Job Policies

Every day elected officials and the bureaucrats they are in charge of should wake up and ask themselves, “What can I do to make it easier for jobs to be created in my area of responsibility?” It should not be lost on anyone that states that have high taxes and lots of regulations are seeing people and businesses move to lower-tax states, which of course makes it harder for those states to collect enough taxes to pay for the services they provide.

There have to be rules, of course. But the rules and regulations should be the minimum needed to keep the barriers to entry for new businesses as low as possible. It is one thing to set rules for public safety. It is another to require dozens of forms and lawyers to open a small business. Running a business is hard enough without extra paperwork required by bureaucrats who don’t have any skin in the game and can respond when they are ready and not when needed.

A proper job policy begins with educational opportunities, and that means a proper education in schools that get that their job is teaching children. I (John) have seven kids (five adopted), and their education needs have been widely divergent. I have had to shop schools more than once to find a school where one particular kid could thrive. Schools that teach to one size fits all or, at the most, a few sizes are outmoded in a modern world. Schools that are organized for the benefits of teachers’ unions don’t work at the primary job. We need to recognize that we need schools that cater to the diverse learning styles of the kids.

We have to recognize that we have to compete with China, India, Indonesia, and Germany (and a hundred other countries). At one time, we were up to the task, but we seem more hesitant these days. We need to recognize that unique skill that is the young American entrepreneur and work to train and find more of them, and it is in our schools that we find the breeding grounds for tomorrow’s jobs.

Think about Tax Policies to Encourage New Businesses

Without jobs and lower unemployment, we have no real chance to get our fiscal house in order without really significant pain. The first order of business is to find ways to create new jobs. Since business start-ups are the true source of net new job creation, let’s figure out what we can do to encourage them. Why not tell anyone who starts a business within the next three years that if he sells his business after five years, and has created some minimum number of new jobs, that he can sell his business when he wants for zero capital gains? That seems to us an incentive we can believe in.

And let’s compete for global jobs. Let’s offer international companies the opportunity to create a company in the United States and have their corporate taxes only be a low number for 10 years and then rise slowly after that. Why not 12 percent to compete with Ireland? Of course, that might give them an advantage with existing companies, so why not cut corporate taxes to where we can compete internationally?

There have to be taxes, but we can figure out how to restructure our tax code. As we finish this book, Erskine Bowles and Alan Simpson have put together a proposal to restructure the tax code, putting a top rate at 23 percent, but taxing capital gains and dividends at the same rate. They have a very interesting table with their release that shows what keeping certain tax expenditures would cost. For instance, if we decided that we wanted to keep the child tax credit and the earned income credit, it would cost an extra 1 percent of tax rate for everyone. The mortgage interest tax deduction would cost another 4 percent of tax rate for everyone. Considering that 40 percent of Americans do not own homes and a large percentage of those who do own owe nothing or very little, maybe it is something to consider.1

Another bipartisan group, headed by former Senator Pete Domenici and President Clinton’s Office of Management and Budget Director Alice Rivlin, put forth a plan with two rates of 15 percent and 27 percent and a sales tax of 6.5 percent.

We hope that as more proposals are offered that the designers use the same format as Erskine Bowles. Show us what each large item in the tax code costs, and let us decide what we think is a good investment of our tax dollars and what we don’t.

We won’t go into details on these plans because there will be lots of others coming out soon. But it is refreshing to perhaps be at the beginning of a real conversation on reforming taxes in such a way as to encourage savings and new business while also getting the fiscal deficit under control.

We are dealing with the aftermath of the third bubble in the last 10 years, the last one being in government. And it is the one that is going to create the most problems as we try to solve how to shrink the government (at all levels) back down to a size that we can afford and that will not crowd out new business and private investment. It will not be easy, but the fact that we are seeing bipartisan proposals (which are bringing howls from both sides of the aisle) is encouraging. It shows that there are people who are beginning to get it.

Finally, we are optimistic that we will in fact figure it out. Over time, those new jobs will come as a new generation of American entrepreneurs figure out how to create a business that gives us goods and services we want. Just as we had personal computers and the Internet come along, we are going to see revolutions in the biotech, wireless telecom (you ain’t seen nothing yet!—there is a whole new wireless build-out coming), robotics, electric cars, smart infrastructure, and so much more.

As a reminder, in the late 1970s, when the Japanese were kicking our brains in, inflation was roaring, interest rates were pushing 20 percent, unemployment was almost 10 percent, and businesses were struggling, the correct answer to the question “Where will the jobs come from?” was “I don’t know, but they will.”

It is what we do.

1John’s daughter Tiffani and son Henry with new mortgages would probably vigorously disagree!