CHAPTER TEN

The European Periphery

A Modern-Day Gold Standard

Europe exemplifies a situation unfavorable to a common currency. It is composed of separate nations, speaking different languages, with different customs, and having citizens feeling far greater loyalty and attachment to their own country than to a common market or to the idea of Europe.

—Professor Milton Friedman, The Times, November 19, 1997

There is no example in history of a lasting monetary union that was not linked to one State.

—Otmar Issuing, Chief Economist of the German Bundesbank in 1991

The countries of the European periphery are falling like dominoes due to too much debt. Greece required a bailout from the European Union and the IMF in May 2010. Ireland required one a few months later in November 2010. As we write this book, Portugal and Spain are next in the sights of the speculators. Much like the subprime crisis in the United States took down the mortgage lenders first, then Bear Stearns and then Lehman Brothers, the problems of too much debt are threatening to bring down European states.

During the good years, Portugal, Ireland, Italy, and Greece enjoyed the benefits of being in the euro, but now all the imbalances that have built up over time need to be redressed. This chapter deals with how these countries got there, what the current problems are, and possible ways out.

The Euro: A Suboptimal Currency Union

It may seem obvious to state it, but Europe is not a country. Europe is many things. It is a continent. It is an idea of better things to come for many immigrants who come to its shores from Africa and the Middle East. But it is also a currency area. And it is not a good one.

Many of us take our national currencies for granted, and we assume that we have always had dollars, pounds, yen, or euros. In fact, for a long time, individual banks issued notes promising the holder to exchange the notes for gold. The idea that a currency should exactly equal national territory is really one that came about very late in history.

Before the euro was created, Robert Mundell, an economist, wrote about what made an optimal currency area. His writing was so important that he won a Nobel Prize for his work. He wrote that a currency area is optimal when it has:

- Mobility of capital and labor

- Flexibility of wages and prices

- Similar business cycles

- Fiscal transfers to cushion the blows of recession to any region

Europe has almost none of these. Very bluntly, that means it is not a good currency area.

The United States is a good currency union. It has the same coins and money in Alaska as it does in Florida and the same in California as it does in Maine. If you look at economic shocks, the United States absorbs them pretty well. If you’re unemployed in southern California in the early 1990s after the end of the Cold War defense cutbacks or in Texas in the early 1980s after the oil boom turned to bust, you can pack your bags and go to a state that is growing. That is exactly what happened. This doesn’t happen in Europe. Greeks don’t pack up and move to Finland. Greeks don’t speak Finnish (no one does outside of Finland). And if Americans had stayed in California or Texas, they would have received fiscal transfers from the central government to cushion the blow. There is no central European government that can make fiscal transfers. So the United States works because it has mobility of labor and capital, as well as fiscal shock absorbers.

The modern euro is like a gold standard. Obviously, the euro isn’t exchangeable for gold, but it is similar in many important ways. Like the gold standard, the euro forces adjustment in real prices and wages instead of exchange rates. And much like the gold standard, it has a recessionary bias. Under a gold standard, the burden of adjustment is always placed on the weak-currency country, not on the strong countries.

Under a classical gold standard, countries that experience downward pressure on the value of their currency are forced to contract their economies, which typically raises unemployment because wages don’t fall fast enough to deal with reduced demand. Interestingly, the gold standard doesn’t work the other way. It doesn’t impose any adjustment burden on countries seeing upward market pressure on currency values. This one-way adjustment mechanism creates a deflationary bias for countries in a recession. The deflationary bias also makes it likely, at least by historical measures, that we will catch hell from the Austrians.

Economists like Barry Eichengreen, arguably one of the great experts on the gold standard and writer of the tour de force Golden Fetters, argues that sticking to the gold standard was a major factor in preventing governments from fighting the Great Depression. Sticking to the gold standard turned what could have been a minor recession following the crash of 1929 into the Great Depression. Countries that were not on the gold standard in 1929 or that quickly abandoned it escaped the Great Depression with far less drawdown of economic output.

Before we begin, we need to introduce a very important distinction. In Europe, the so-called core is Germany, France, Netherlands, and Belgium. They are in general wealthier, have higher price stability, and have much more integrated economies. The periphery is Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain (known often as the PIIGS). These countries historically are poorer (or regions within them are), have less price stability, are not well integrated with Germany and France, and have less coordinated business cycles. The difference between the core and periphery leads to all sorts of problems that we’ll explain in this chapter.

Over the past 10 years, the European periphery has experienced large increases in wages and prices compared with the core. While prices and wages were stagnant in Germany, they were increasing at a rapid rate in the periphery. This made the periphery very uncompetitive relative to Germany and the rest of the core. The result? The periphery countries were importing a lot more than they were exporting and were running large current account deficits. The only way to fix this is through a real cut in wages and prices, an internal devaluation, or deflation. This is hugely contractionary and poses tremendous problems.

Rapidly rising prices with low interest rates created the problem of negative real interest rates in the periphery. In plain English, that means that if the borrowing rate is 3 percent while inflation is 4 percent, you’re effectively borrowing for 1 percent less than inflation. You’re being paid to borrow. And borrow they did. The European peripheral countries racked up enormous debts in euros, a currency that they can’t print.

The United States, the United Kingdom, and Switzerland have monetized liabilities to provide liquidity to banks, ease fiscal expansion, influence long-end rates, and weaken their currency. The European periphery (the proverbial PIIGS: Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, and Spain) does not have that option. The only historical analogy to the situation of the European periphery is countries that experienced deflation while under a gold standard: where debts had to be paid down in a currency—that is, gold—that they could not print.

Germany refuses to reduce its enormous trade surplus and increase its domestic consumption to rebalance Europe and help the weaker economies grow out of their difficulties. Remember, for every deficit, there has to be a surplus. Instead, Germany is busy cutting spending and reducing domestic demand, just as much as its periphery neighbors. Because the euro is like a gold standard, it is a regime with a strong deflationary bias. The burden of adjustment falls on the deficit countries in the periphery who are forced to deflate.

Unlike the gold standard, it is almost impossible to leave the euro. The Maastricht treaty was very clear about how to get into the euro but said nothing about how to get out. Indeed, the mechanics of a country leaving the euro would be so messy that even if it were the right policy in the long run, most politicians and businesspeople would oppose it in the short run. Consider the following in the event of a breakup of Italy leaving the Eurozone:

Market participants would be aware of this fact. Households and firms anticipating that domestic deposits would be redenominated into the lira, which would then lose value against the euro, would shift their deposits to other euro-area banks. A system-wide bank run would follow. Investors anticipating that their claims on the Italian government would be redenominated into lira would shift into claims on other euro-area governments, leading to a bond-market crisis. If the precipitating factor was parliamentary debate over abandoning the lira, it would be unlikely that the ECB would provide extensive lender-of-last-resort support. And if the government was already in a weak fiscal position, it would not be able to borrow to bail out the banks and buy back its debt. This would be the mother of all financial crises.1 [Not unlike the process Greece is in!]

The consequences are too dire for most politicians to even consider. That is why the euro most likely will plod along as politicians do everything they can to keep the project going. This will have profound implications for economic growth, deflation, and financial markets.

The euro is not an economic currency. It is a political one, and as long as there is the political will, it will remain a currency. Ironically, it is the well-off nations like Germany or the Netherlands (where we sit today editing yet another final draft of this book) who could exit without their own internal crisis. Not that either country would, and their banks do own a lot of peripheral country debt.

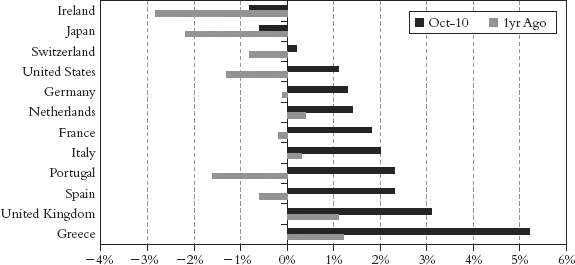

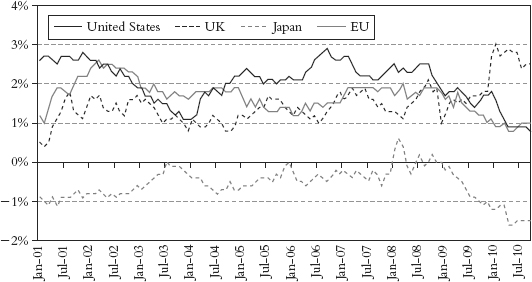

What does the evidence for deflation and contraction show so far? European inflation is running below that of most other countries. Arguably, we will see inflation in countries that can monetize debt and see deflation in those that can’t. Unsurprisingly, Figure 10.1 shows that the highest rates of inflation are in the United States and the United Kingdom, while the lowest are in the Eurozone countries and in Japan, which is trapped in deflation.

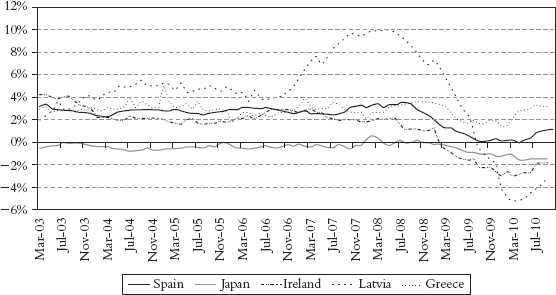

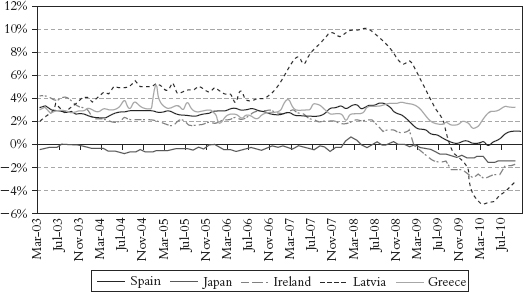

It is worth noting that the European periphery has the prime candidates for protracted deflations. (See Figure 10.2.)

Figure 10.2 Core CPI: Spain, Latvia, Ireland, Greece, and Japan

Source: Bloomberg, Variant Perception.

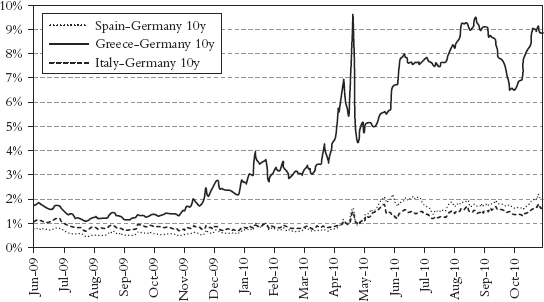

One of the main things investors and journalists have wanted to talk about this past year is the unfolding situation in Greece and the periphery. Figure 10.3 shows this starkly. The problems are not new, but the markets are now realizing the depth of the problem.

Let’s look at an excerpt from the September 2010 issue of Vanity Fair by Michael Lewis.2

As it turned out, what the Greeks wanted to do, once the lights went out and they were alone in the dark with a pile of borrowed money, was turn their government into a piñata stuffed with fantastic sums and give as many citizens as possible a whack at it. In just the past decade the wage bill of the Greek public sector has doubled, in real terms—and that number doesn’t take into account the bribes collected by public officials. The average government job pays almost three times the average private-sector job.

The national railroad has annual revenues of 100 million euros against an annual wage bill of 400 million, plus 300 million euros in other expenses. The average state railroad employee earns 65,000 euros a year. Twenty years ago a successful businessman turned minister of finance named Stefanos Manos pointed out that it would be cheaper to put all Greece’s rail passengers into taxicabs: it’s still true. “We have a railroad company which is bankrupt beyond comprehension,” Manos put it to me. “And yet there isn’t a single private company in Greece with that kind of average pay.”

The Greek public-school system is the site of breathtaking inefficiency: one of the lowest-ranked systems in Europe, it nonetheless employs four times as many teachers per pupil as the highest-ranked, Finland’s. Greeks who send their children to public schools simply assume that they will need to hire private tutors to make sure they actually learn something. There are three government-owned defense companies: together they have billions of euros in debts, and mounting losses.

The retirement age for Greek jobs classified as “arduous” is as early as 55 for men and 50 for women. As this is also the moment when the state begins to shovel out generous pensions, more than 600 Greek professions somehow managed to get themselves classified as arduous: hairdressers, radio announcers, waiters, musicians, and on and on and on. The Greek public health-care system spends far more on supplies than the European average—and it is not uncommon, several Greeks tell me, to see nurses and doctors leaving the job with their arms filled with paper towels and diapers and whatever else they can plunder from the supply closets.

The Greek people never learned to pay their taxes . . . because no one is ever punished. It’s like a gentleman not opening a door for a lady.

Where waste ends and theft begins almost doesn’t matter; the one masks and thus enables the other. It’s simply assumed, for instance, that anyone who is working for the government is meant to be bribed. People who go to public health clinics assume they will need to bribe doctors to actually take care of them. Government ministers who have spent their lives in public service emerge from office able to afford multi-million-dollar mansions and two or three country homes.

The level of change that will be needed in Greece is almost beyond description. As Lewis points out, it is more than just balancing a few budgets and making some cuts. It demands a change in the national character—in the way of doing things that everyone has gotten used to.

The leaders of Europe make brave statements that no European Union member can be allowed to default. There must be a way. And yet, the reality is that the solution is for the Greeks to borrow even more money that they cannot pay. Default is not only possible; it is likely.

Greece is a disaster, but it is a small one. Greece is a gnat on an elephant’s backside. Greek nominal GDP is about 2 percent of the euro area total. Spain’s GDP is over 12 percent of the euro area.

Spain had the mother of all housing bubbles. To put things in perspective, Spain now has as many unsold homes as the United States, even though the United States is about six times bigger. Spain is roughly 12 percent of the EU GDP, yet it accounted for 30 percent of all new homes built since 2000 in the EU. Most of the new homes were financed with capital from abroad, so Spain’s housing crisis is closely tied in with a financing crisis.

The impact on the banking sector will be severe. Consider this: The value of outstanding loans to Spanish developers has gone from just €33.5 billion in 2000 to €318 billion in 2008, a rise of 850 percent in eight years. If you add in construction sector debts, the overall value of outstanding loans to developers and construction companies rises to €470 billion. That’s almost 50 percent of Spanish GDP.

The magnitude of the Spanish problem is staggering and will overwhelm all the benefits of dynamic provisioning. Spain has 613,512 homes that are finished but unsold as of December 2008, according to the Spanish Housing Ministry. To that number, you’d have to add 626,691 homes that were under construction as of that date. Of those, 250,000 were sold (but subject to cancellation), and the others were ready to hit the market. So conservatively, Spain has more than 1 million unsold homes. Unfortunately, many of the homes are on the coast, and without a return of overleveraged British tourists, they are likely to remain unsold. Spain’s homes are all in the wrong places.

Spain’s building stocks bubble looks very much like the U.S. bubble and other classic bubbles. It went up tenfold and then went down 90 percent. The math is very simple.

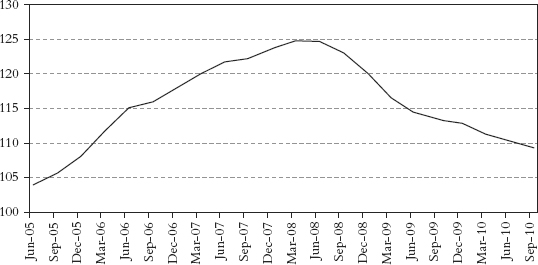

Given this woeful state of affairs, you might assume Spanish house prices had suffered like U.S. house prices. This is not the case. As Figure 10.4 shows, according to official statistics, Spanish house prices are down little more than 10 percent from their peaks.

Figure 10.4 Spanish House Price Index (Housing Ministry data)

Source: Bloomberg, Variant Perception.

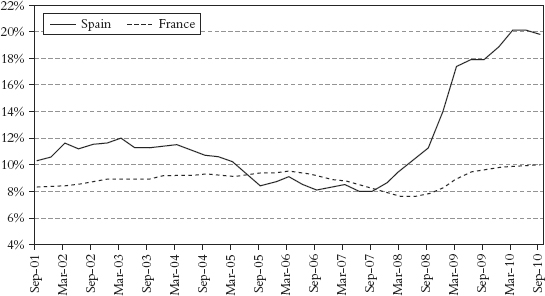

Given the mother of all housing bubbles and a lack of competitiveness, Spain is likely to face a prolonged downturn and very large budget deficits for some time to come. The Spanish unemployment rate is double the average of a core country like France, as Figure 10.5 shows. Even with recent labor market reforms, the structural problems remain.

The problems of the core versus the periphery, however, will not go away. Irrespective of the current Greek crisis, European spreads should fundamentally trade much wider than they did during the quiet period of 2000 to 2010. As we write in late 2010, interest rate spreads of the periphery countries are once again rising back to crisis levels, signaling another sovereign debt crisis. Investors have been complacent for too long and willing to lend at the periphery at rates that made no sense, based on their poor fiscal credibility and their dim outlook for growth following a decade of inflation, excess consumption, and living beyond their means.

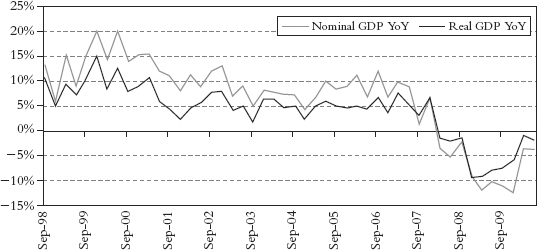

What is ahead for the European periphery? The European periphery is likely to follow in the footsteps of Ireland. Of all European countries, Ireland is now the most advanced in its own deflationary drama. Ireland is experiencing severe deflation, and even though GDP growth is turning up quarter on quarter, it is still deflating nominally (Figure 10.6).

Deflation will exacerbate government deficits in the long run, as companies pay nominal, not real, taxes. (In a deflationary environment, real—after deflation—taxes could be increasing, yet nominal taxes decreasing.)

The periphery countries will slash government spending to keep the markets at bay, which will have short-term contractionary effects. The longer-term squeeze will come from their overvalued real effective exchange rates and lack of competitiveness that can be fixed only through years of deflation.

Not all countries can export their way back to prosperity. This includes Greece, Spain, and Portugal. As the periphery countries necessarily reduce their deficits, what must happen to maintain balance? Either European surplus countries reduce their surplus, or on net Europe must reduce its surplus, in which case China must reduce its, or the United States must increase its deficit.

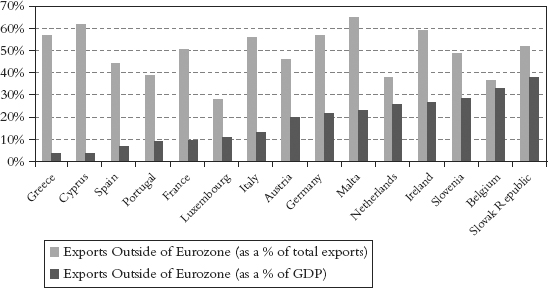

A weak euro will not help the European periphery. As Figure 10.7 shows, exports outside the Eurozone as a percentage of GDP are very low for Greece, Spain, and Portugal. Except for Ireland, the PIIGS are not very open economies, and most of their exports are to other European countries.

Figure 10.7 European Exports Outside the Eurozone

Source: Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, “The Role of External Demand in the Eurozone,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, May 27, 2010, www.petersoninstitute.org/realtime/index.cfm?p=1595.

Only internal measures to make wages and prices more flexible and to improve the labor market and improve skills will have any impact, and these cannot happen overnight.

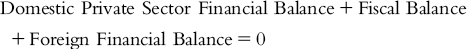

The European periphery faces a period of debt deflation. As we have pointed out elsewhere, the public sector and private sector in periphery economies cannot deleverage at the same time without running a trade surplus. (The problem is that Germany and China aren’t about to start running deficits.) This is true for mathematical reasons that are inescapable. Earlier, we showed that the following relationship is true:

This is an economic identity that can’t be violated. Simply put, the changes in one sector’s financial balance cannot be viewed in isolation. If government wants to run a fiscal surplus and reduce government debt, it needs to run an even larger trade surplus, or else the domestic private sector will need to engage in deficit spending. The only way that both the government and the private sector can deleverage is if the countries run large current account surpluses; in other words, your demand has to come from another country.

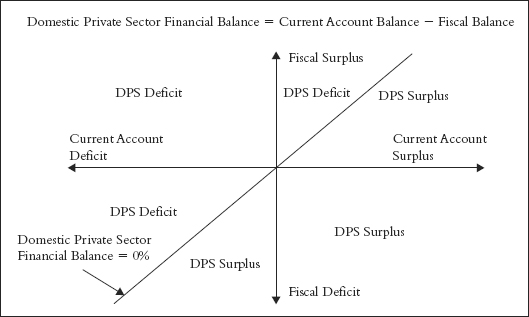

The map in Figure 10.8 is illuminating.

Figure 10.8 Three-Sector Financial Balances Map

Source: Rob Parenteau, MacroStrategy Edge, www.creditwritedowns.com/2010/03/leading-piigs-to-slaughter.html.

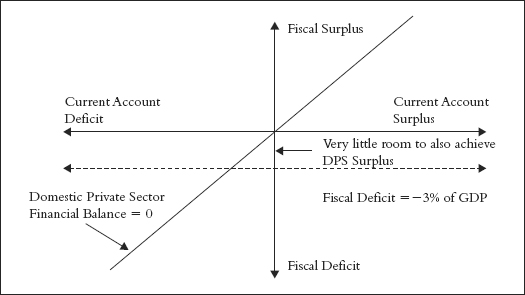

What does this mean for Europe? In Europe governments by treaty are not supposed to run deficits of more than 3 percent of GDP (although they routinely do). If you look at it according to the Maastricht deficit criteria, as seen in Figure 10.9, you will see that the room for maneuver is very limited.3

Figure 10.9 The EMU Triangle: When FX Policy Is Constrained and Current Account Surplus Is Unachievable

Source: Rob Parenteau, MacroStrategy Edge, www.creditwritedowns.com/2010/03/leading-piigs-to-slaughter.html.

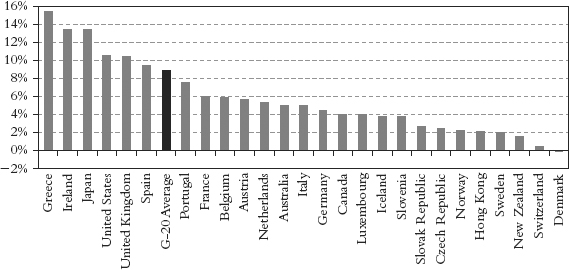

The room for adjustment is simply too small. As Figure 10.10 shows, the required fiscal adjustment in most European countries is simply too large. There is literally no chance that almost any of the European periphery countries (with the exception of Italy, which has a path if it has the political will) will succeed in their goal of abiding by the Maastricht criteria and deleveraging at the same time. To do so will require that these countries reduce their trade deficits by enough that it could only mean a local depression for some time. It would mean depressed incomes and wages, lower tax revenues, and in short, a very ugly picture.

Figure 10.10 Required Fiscal Adjustment between 2010 and 2020, According to IMF

Source: Bloomberg, Variant Perception.

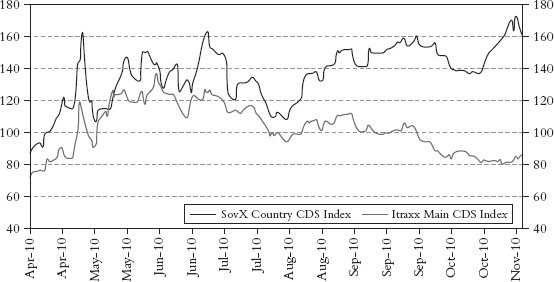

The extremely low likelihood for success is already reflected in the marketplace. Market participants are beginning to believe governments will not pay back their debts. Governments are now held in such low regard by investors that in many countries, corporate bonds trade at tighter spreads than their equivalent sovereigns. Figure 10.11 shows that for the first time ever, corporate CDSs (credit default swaps, a way to hedge your bond holdings) are tighter than sovereign CDSs.

Some Countries Recover; Others Don’t

Currently, the world is caught in a tug-of-war between deflation and inflation. The world faces powerful deflationary forces that have induced equally powerful inflationary responses from governments around the world. The effects will not happen everywhere and to all assets at the same time. Some regions of the world will experience growing inflation, while other parts will be trapped in a deflationary spiral; some assets will move up in price, while others stagnate or even deflate.

Interestingly, so far only Japan is showing negative core inflation, but the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and France all have relatively high core inflation, as Figure 10.12 shows.

Figure 10.12 Core CPI: United Kingdom, United States, Japan, and European Union

Source: National Statistics, Variant Perception.

On the other hand, the countries that are genuinely experiencing the beginning of what will be a prolonged deflationary period are Spain, Ireland, Greece, Japan, and Baltic countries like Latvia (Figure 10.13). These are the countries with the greatest imbalances. So far, they have had no meaningful reforms.

Figure 10.13 Core CPI: Spain, Ireland, Latvia, Japan, and Greece

Source: National Statistics, Variant Perception.

Central banks are overwhelmingly more concerned about deflation than about inflation. It is precisely the deflationary fear—the fear of the liquidity trap—that will drive central banks to be extremely loose with their monetary policies. Central banks are afraid of the fall in monetary velocity, and because of this, they will continue to flood the world with money until they are convinced velocity will rise. The current low levels of CPI—itself only one measure of inflation—will give them false confidence that they have a sweet spot in which they can print money with impunity without causing inflation.

Bottom line? We expect Greece to default on its debt at some point. You cannot keep on adding to debt when too much debt was the original problem. Greece cannot grow its way out of its problems. Germany has begun to make it known that they expect bondholders and not just German taxpayers to take some of the pain of restructuring.

Sadly, we must say the same for Portugal. They just don’t seem to get it. But in the end, the market will force them to.

Spain? It is hard to see a way out, short of willingly throwing themselves into a major depression, which does not really solve the problem. Spanish debt is going to suffer a haircut, and that is both government and private debt. It is just too much. For more in-depth information on the Spanish problem and the problems of other peripheral countries, you can go to www.johnmauldin.com/PIGS and see research from Jonathan Tepper of Variant Perception and other related material. Just type in your e-mail address as your name and Endgame as the password.

And Mother Ireland (at least to John)? They are making the right and difficult efforts, as opposed to Greece. Their hearts (as all Irish hearts are) are in the right place. But it is a very deep hole in which they find themselves. One way or another, they will muddle through. That is what the Irish have done for centuries. We would not want to bet on their government bonds, but a home in the country might be a good wager.

Want a European success story? Go to tiny Malta, an island full of history in the Mediterranean. Not really the population of a decent city, they are a demonstration of what can happen when politicians of all sides can come together. Malta is really a small town where everybody knows everybody.

Malta seems to get that they have no natural advantage. So the business of Malta became business. Whatever it takes to attract investments and jobs is the first order of the day. Like politicians everywhere, they fight. But they seemingly get what it takes to keep their economy growing. Would that the rest of the world could take a lesson. Seriously.