CHAPTER ELEVEN

Eastern European Problems

We must pay the debt precisely and punctually, even if we destroy the economy in so doing.

—Katalin Botos, Secretary of State in the Hungarian Finance Ministry (1990–1993)

Eastern Europe faces daunting structural issues. A decade of excess lending, wage and price growth, and large current account deficits has created major imbalances. To make things worse, most of the borrowing for the Baltics, Romania, Bulgaria, and Hungary was in foreign currencies.

Eastern Europe, much like Spain and Ireland, will face deflation and high unemployment for some time. At best, we are likely to see an L-shaped recovery for Eastern Europe. Figure 11.1 shows the real effective exchange rates of Eastern European countries. It is clear that they have become far less competitive against a benchmark country of the European core, like Germany. (This is the same problem Portugal, Ireland, Greece, and Spain face, but on a smaller scale.)

In this chapter, we look at the Baltics and Hungary, the two poster children of what can go wrong when you have too much lending and housing bubbles.

Hungary: Damned If They Do, Damned If They Don’t

One of the outcomes of the economic crisis is that we all became a little more financially literate. As economic news suddenly moved to the top of news bulletins and migrated from the graveyard pages of newspapers to become front-page headlines, the jargon of finance began to enter the common lexicon. Obscure terms such as collaterized debt obligation, LIBOR, securitization, and credit default swap became fairly commonplace. One of these terms was the so-called carry trade. This usually referred to the Japanese carry trade. In essence, investors exploited Japan’s very low interest rates by borrowing in yen and using the funds to buy assets in another country, such as the United Kingdom or the United States (remember those days?), that earned a much higher rate of interest.

Much less discussed, though, was the Eastern Europe carry trade. Several Eastern European countries had very high interest rates in the years leading up to the banking crisis, largely a legacy of trying to bring down uncomfortably high rates of inflation. Hungary’s rates, for instance, reached 12.5 percent in 2004 to try to combat a rising inflation rate that eventually peaked out at well over 7 percent.

This made borrowing in Hungary very expensive. In neighboring Austria, the banks there had started to offer loans and mortgages to their customers in Swiss francs. Rates in Austria, at 2 percent, may have been lower than in Hungary, but in Switzerland, they were even lower, at around 0.50 percent. Why would Austrians borrow at 2 percent when they could just as easily borrow at 0.50 percent? The same question applied to Hungarians, except the difference was much bigger. So the Austrian banks, many of which also had branches in Hungary (a throwback to the days of the Austro-Hungarian Empire), began to engage in the same business there, lending Swiss francs to Hungarian borrowers.

Unsurprisingly, this proved to be very popular in Hungary. All of a sudden, people who were unable to afford a mortgage in Hungarian forints because of the prohibitively high interest rates were able to get a seemingly great deal in Swiss francs (or euros, but most of the borrowing was from Switzerland). Property prices surged, and the economy appeared to flourish. It was not long before the majority of debt in Hungary was denominated in a foreign currency. Indeed, as Figure 11.2 shows, Hungary was one of the worst offenders in this respect, with almost two-thirds of household debt (mortgages and consumer loans) in a foreign currency.

Figure 11.2 Burdensome (total debt—household and corporate—as percentage of GDP, end 2009)

Source: The Economist, Austrian Nationalbank.

As we have learned throughout this book, there is no such thing as a free lunch. Sure, you can borrow much cheaper in a foreign currency and save a lot of money to begin with. But what of the extra risks, many of which your average borrower is blissfully unaware of until it is too late?

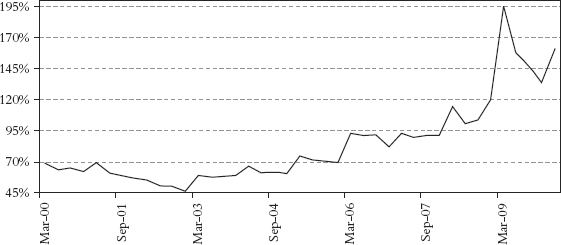

Well, when borrowing in a foreign currency, you are exposed to the foreign exchange movements of the two currencies. Imagine as a Hungarian you borrowed in Swiss francs to buy a house in Hungary. When you came to repay the loan, if the Hungarian forint had weakened significantly against the Swiss franc, you would have to find more forints to pay back what you owe in francs. As exchange rates can move fast and far, doing so could be very costly. This means Hungary’s net external debt/GDP ratio has the ability to balloon instantly with any weakness in the Hungarian forint. Indeed, the debt almost doubled overnight as the forint weakened in late 2008, as Figure 11.3 shows.

Figure 11.3 Hungary: Net External Debt/GDP Percentage

Source: National Statistics, Variant Perception.

This is a risk that has far from disappeared. As the exchange rates of the Swiss franc against the Hungarian forint in Figure 11.4 show, servicing foreign debt in Hungary is as difficult as it has ever been:

Hungary’s fiscal situation deteriorated fast during the financial crisis. Output collapsed, and the government, in common with many other countries across the globe, had to ramp up borrowing to make up for the shortfall in tax revenues. The result? Despite getting its budget deficit down to one of the lowest in Europe, Hungary now has one of the highest debt-to-GDP ratios in the region. (See Figure 11.5.)

Figure 11.5 Emerging Europe: Government Debt and Revenue 2009

Source: National Statistics, Variant Perception.

It was thus no surprise that Hungary, along with Latvia, became one of the first countries postcrisis to call in the IMF for financial aid, obtaining a $15 billion loan from the organization in November 2008. The loan had the usual tough conditions that would ensure the country’s fiscal health was restored so further bailouts could be avoided. There is no doubt the loan helped stabilize the country’s finances through the darkest hours of the crisis. Lately, however, there has been friction between the current Hungarian government and the IMF. This is where Hungary becomes very important and why we should pay close attention.

Hungary has had austerity measures in place from as early as 2006—well before the IMF came in with its loan—as the government fought to reduce a swelling budget deficit to be ready to comply with European Union requirements. But now we are seeing reform fatigue, which is fairly usual in response to tough economic medicine. As Barclays Capital notes in a 2010 research piece, “‘Stabilisation fatigue’ is a common phenomenon that sets in a year or two into a tough program, and the outcome of that process is extremely difficult to predict. In short, the recent early success of the Greeks’ courageous efforts should be applauded, but investors would be well advised to keep in perspective that sovereign risks very much remain a reality.”1

So although it may appear that countries like Greece have taken the steps necessary to solve their problems and we can all go back to sleep, it is very unlikely that we are in the clear yet, as Hungary makes clear. If we watch Hungary, we will have a good idea how things will play out in many other parts of the world.

But ongoing austerity fatigue is only one of Hungary’s problems. With a heavily indebted private and public sector, Hungary is going to have to look to its export sector to rejuvenate its economy and reduce its foreign debt. There are several problems associated with this. First, Hungary’s export sector is too small on its own to pull the economy forward. Second, Hungary will be trying to increase exports at the same time countries all over the world, from China to Spain, from the United Kingdom to Greece, are trying to do the same. Competition is intense.

However, the most crushing problem of Hungary’s is directly a result of having so much of its debt denominated in a foreign currency. If the Hungarian central bank cuts rates to try to make the forint cheaper and thus make Hungary’s exports more competitive, it risks a wave of private-sector defaults. Remember all those mortgages in Swiss francs we mentioned? Well, those loans would suddenly balloon in value to the extent that many borrowers would have to throw in the towel. Property prices would collapse, and the economy would sink.

And there would be a risk that trouble could spread abroad. The banks in Austria who had originally made the loans would be at risk of going under, creating all sorts of problems in Austria and further afield. It would not be pretty. (Remember, it was the default of a little-known Austrian bank called Credit Anstalt that triggered the global financial crisis in 1931.)

The European Central Bank (ECB) has determined that Greece is too big to fail and is stepping in. But if there is a further crisis in Hungary and other Eastern European countries, the bank problems in Austria would be so massive that the banking sector in Austria would be too big to save for the Austrian government, not dissimilar to the situation in Iceland.

The Austrian banks have lent approximately 140 percent of the country’s GDP to Eastern Europe. There is no way the Austrian government could bail them out in the event of a real crisis. The ECB would have to step in, and that, gentle reader, will not bode well for the euro. Nor will it sit well with voters in Germany and other core countries.

But neither can the central bank in Hungary risk maintaining rates at their current high level for too long. This will mean choking off the competitiveness the country needs to boost its export sector and repair its economy. Policy makers in Hungary are in an impossible position; they are damned if they do and damned if they don’t.

Hungary will be important to watch as we move toward endgame. The country will remain a potential hand grenade in the European region—and perhaps further afield—as long as its foreign exchange–denominated loans remain so high. It wouldn’t take much to kick off a wave of defaults in Hungary, which would mean grave problems for European banks. And as we have learned so starkly throughout this crisis, when banks have a problem, we all have a problem.

Yet the greater implications of Hungary’s plight lie in its bid to cut costs and restore fiscal order. Hungary is a leading indicator when it comes to experiencing the effects of austerity, having lived through such circumstances for more than four years now. Reform, or stabilization, fatigue is common one to two years into public belt-tightening programs. We should not be so complacent as to think austerity programs recently agreed to in countries like Greece and Ireland will be the end of the matter. Remember, the light at the end of the tunnel is sometimes another train.

The Baltics: How to Destroy Your Economy and Keep Your Peg

The Baltic countries—Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia—lie on the Baltic Sea in the far eastern fringes of Europe. Their economies are very small, even smaller than Greece’s, but like Greece, they matter. It was even before Greece came under scrutiny that the Baltic countries, especially Latvia, came under the spotlight. Indeed, it was really the Baltics that first alerted investors to what Ken Rogoff and Carmen Reinhart so elegantly demonstrated in their book This Time Is Different, that what normally follows a financial crisis are sovereign crises.

It isn’t always obvious after the initial financial cataclysm where the first domino will fall. The financial crisis in the 1930s after the Wall Street crash of 1929 started in Austria, of all places. The Asian crisis in 1997 could have had many triggers, given the enormous economic imbalances in the region at that time, yet it was a sell-off in the Thai baht that proved to be the catalyst. In our fingers of instability analogy that we discussed in Chapter 2, it is not the grain of sand that’s the real cause for the avalanche, but the level of instability in the overall system. After a financial collapse, the system is in a very fragile state; we know it might only take one grain of sand to create an avalanche, but heaven knows which one! After Lehman fell, there were many candidates for the first sovereign to get into trouble. It turned out to be Latvia (closely followed by its Baltic neighbors) that would earn the dubious distinction of being one of the first countries postcrisis to have to call in the IMF for assistance.

First, let’s look at why the guns of the world’s investors turned to the Baltics during and after the financial crisis. Then, we’ll look at what this means for other potential sovereign mishaps waiting to happen around the globe.

The Baltic countries regained their independence from the Soviet Union in the early 1990s following the collapse of communism. They were enthusiastic in leaving their Soviet past behind and embracing the West, with all three countries first joining NATO and then the European Union. A further ambition of Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia was to join the euro, so all three adopted currency pegs with the euro, a precondition for joining the common currency.

A currency peg is when a country agrees to fix its exchange rate to another. For example, the Latvians fixed the lats at 1 EUR = 0.702804 LVL. If people want lati at a higher price than that, the central bank has to print them and buy euros. If people want to exchange their euros at a higher price than that, then the central bank has to raise interest rates and withdraw money from the local economy to strengthen the currency. Effectively, pegs imply giving up control of your own money supply and handing it over to the market or to a foreign central bank. However, it can provide a higher degree of stability in good times.

Here’s where Baltic countries’ problems started. By fixing their currencies to the euro, it made it a lot easier for foreign banks to start lending to people in the Baltics. The peg eliminated exchange rate risk. Take Swedish banks as an example. They had a lot of spare cash—deposited by conservative Swedish savers—that they wanted to lend out. Sweden has many historical ties with Latvia (and the other Baltic countries) and is one of its largest trading partners. This has led to Swedish banks having subsidiaries in Baltic countries. Once the peg came into being, the Swedish banks went into overdrive, lending euros to their subsidiaries, who exchanged them for local currencies at the fixed peg level. The subsidiaries then lent out the local currency to Latvians, Lithuanians, and Estonians, fueling property prices, funding flashy cars, and creating a latterly unheard-of consumer boom. Suddenly, the modest economies of the Baltic nations looked like they were able to generate a lot of wealth, often ostentatious.

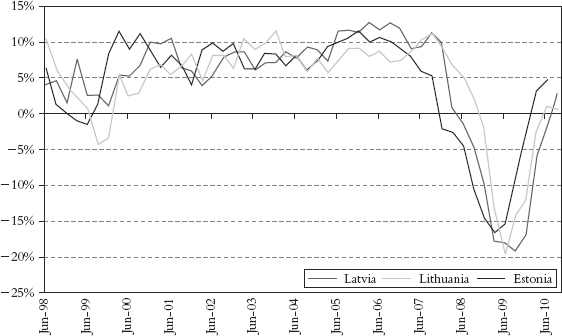

The result? As Baltic residents spent like they’d never spent before, current account (trade) deficits reached eye-watering levels, as Figure 11.6 shows.

Figure 11.6 Baltics: Current Account (as Percentage of GDP)

Source: National Statistics, Variant Perception.

All three countries managed to run up current account deficits of more than 20 percent in 2006 and 2007. This makes the current account deficits seen in the run-up to the Asian crisis of the late 1990s look like Mini-Mes. However, as we’ve seen over and over again in examples throughout this book, markets abhor an imbalance and will move to correct it. The borrowing and spending binge couldn’t continue. Worldwide, fear throttled liquidity as the financial crisis tightened its grip.

Wages had risen in Baltic countries as their credit-driven prosperity increased. This made goods and labor from Baltic countries less competitive. When global growth began to seriously slow in the aftermath of the financial crisis, growth in the Baltic states started to take a serious hit. Government deficits in the Baltic countries grew fast, and it wasn’t long before Latvia had to call in the IMF to formulate a rescue package. This is, of course, when Latvia earned the dubious honor of being the first potential sovereign hand grenade to go off as a result of the financial crisis. The other Baltic countries came under intense scrutiny at the same time, as the three economies were very tightly linked. They were closely followed by the Balkan countries (Romania, Bulgaria, etc.), Dubai, and then the European periphery countries (Iceland, Spain, Greece, Portugal, Ireland). Will there be more to come? We defer to the wicked-smart Professors Rogoff and Reinhart here, who have shown that sovereign crises tend to cluster. So we are pretty sure they would say, resoundingly, “Yes.”

But back to the Baltics. What is the outlook for them now? Well, Latvia is going through one of the most drastic austerity programs we’ve ever heard of. Teachers have seen their wages slashed by almost half, some government employees have had to take pay cuts of 20 percent, and pensioners who work have seen the value of their pensions decimated by up to 70 percent. It makes most other austerity measures attempted elsewhere look like mere tweaking.

To compound the misery, the authorities in Latvia are refusing to drop the currency peg. This would involve a lot of short-term pain, especially for the Swedish banks we mentioned earlier, who have lent heavily in Latvia and the other Baltic countries. However, the end of the currency peg would also mean the government could reverse some of the savage cuts it has made. Breaking the peg would cause the currency to devalue, instantly making Latvian goods and services much cheaper and more competitive. The Latvian economy would grow very quickly, and the fiscal situation would greatly improve. As it stands, nominal GDP has bounced back from the lows in the Baltic countries, but it is still close to zero (Figure 11.7). This is crucial as it means tax revenues will remain depressed, and cutbacks will have to continue.

As it is, it’s the teacher, the pensioner, and the government employee—the little people—who will continue to take the brunt of the adjustment. Instead, the political elites, who would have the most to directly gain from entry to the euro, cling to the peg at all costs. Resentment simmers and threatens to boil over at any time. Not only that, but people are leaving in search of a better life. One survey estimates 30,000 people left Latvia in 2009, and another 30,000 will leave in 2010, which is a worry for a country with a population of a little over 2 million.

Now if you’re ahead of us, gentle reader, you’re probably seeing some similarities between the Baltics and countries we looked at in Chapter 10, like Greece, Spain, and Ireland. They, too, are (effectively) on a currency peg, the euro, and like Latvia and the other Baltic countries, they are having a hard time as wages and costs, rather than the currency, are having to fall to restore competition. We called it “a modern-day gold standard.” The difference with Latvia or Lithuania (but less so Estonia, which was recently approved for euro membership in 2011) is that it could quite easily drop the pegs and revert to local currencies. (The Greek drachma, the Spanish peseta, and the Irish punt are long dead, and resurrecting them would be a huge undertaking.)

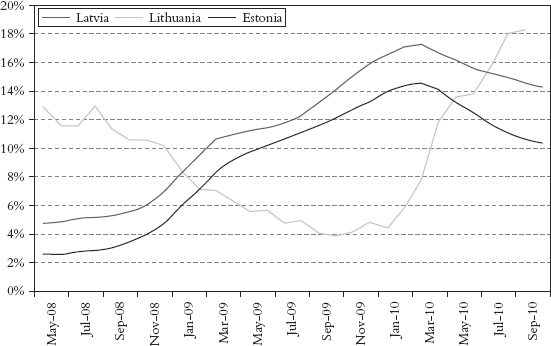

Endgame for the Baltics? Estonia looks like it will be the best of a bad bunch, as its prospects should improve when it adopts the euro in 2011. Lithuania and Latvia, however, will continue to stagnate. Indeed, unemployment in Lithuania continues to increase and has fallen only marginally in the other two Baltic countries. (See Figure 11.8.)

If unemployment does not fall significantly and growth fails to recover, Latvia and Lithuania may yet be forced to exit the peg. Doing so would cause a wave of defaults and a risk of contagion to other countries, including Hungary, which we talked about earlier, and the Balkan countries of Romania and Bulgaria as credit dries up.

We should pay close attention to the Baltic countries. Small as they may be, they are symbolic as to what happens when financial crisis mutates into sovereign crisis. If we want to see the outcome of excessive credit and austerity measures—key for the outlook in the United Kingdom, the United States, Spain, and many other countries—then we need look no further than Latvia and its close neighbors. The Baltics, like Greece, do matter.