CHAPTER TWELVE

Japan

A Bug in Search of a Windshield

Jitters in Europe stemming from the financial collapse of Greece are no longer somebody else’s problem. If Japan fails to tackle fiscal reform, we could come under the control of bodies like the International Monetary Fund, which could tell us what to do in the sovereign matter of fiscal management.

—Prime Minister Naoto Kan, June 17, 2010

Japan is a country that has spent the past 20 years in a hangover from one of the greatest bubbles of the modern era. After the great Japanese equity and land bubble burst in 1990, a long, painful process of deflation and deleveraging started. Even today, the country is still trying to rid itself of deflation. Japan is particularly important because it is the poster boy for the deflationary disease that the Fed is trying to fight.

In this chapter, we’ll look at Japan, a country that has all the conditions for a major upheaval. We’ll look at how the country’s public debt has exploded and how revenues have collapsed over the past two decades. We’ll also look at how quickly the population is aging and what lessons that might have for the United States and Western countries with quickly aging populations. The picture is grim to say the least, but we’ll plunge right in.

I (John) have often written that Japan is a bug in search of a windshield. That may sound harsh, but as you’ll see in this chapter, I’m probably being too kind.

In all of world history, the Japanese bubble in the 1980s will stand out as one of the craziest bubbles ever. At one stage, the Japanese Imperial gardens were reckoned to be worth more than all of the real estate of California.

Partly, the bubble was due to extremely loose Japanese monetary policy. In 1985 at the Plaza Accord, 4 finance ministers and central bank governors of the G5 decided to do something about the strong dollar, and the yen strengthened a lot after that. When the yen strengthened, the Japanese faced a currency loss in the dollar-denominated assets such as U.S. government bonds. The Japanese started bringing their money home, and the yen kept on strengthening. The Bank of Japan tried to fight the strong yen with low interest rates. The official discount rate was lowered five times by February 1987 to help Japanese exports. The official discount rate hit 2.5 percent, the lowest level since World War II. With inflation above the discount rate, money was pretty much free.

Very low rates and a strong yen led to a boom in real estate and stock prices. In a classic bubble dynamic, rapidly rising prices only encouraged people to invest more and more. Japanese companies bought as much real estate in Hawaii and California as they could, including the Pebble Beach golf course, the Hotel Bel Air in Los Angeles, and the Grand Wailea and Westin Maui hotels. Eventually, though, the air came out of the bubble.

The bubble peaked in December 29, 1989, when the Nikkei reached a historic high of 38,915. Within two years of the collapse in the Nikkei, stock prices had declined 60 percent. The only comparable example in the twentieth century was the Great Depression.

Once the bubble had already started to burst and the damage was done, the government and the Bank of Japan very belatedly applied the brakes. In 1989, the Bank of Japan changed to a tight-money policy, and in 1990, after the stock market had started to fall, it raised the official discount rate to 6 percent. Also in 1990, the Ministry of Finance made banks restrict their financing of property. The very tight monetary policy and fiscal tightening only made the downturn that much worse.

By January 1993, reality sank in when the Japanese prime minister finally recognized that the bubble economy (baburu keizai) had collapsed. By that time, it was far too late, and deflation had started to take hold. Prices fell by 1.1 percent in the first quarter of 1993, and by mid-1993, wholesale prices were falling at an annual rate of 4.2 percent. The collapse was extraordinary. In 1990, Japan represented 14 percent of the global economy. Today in 2010, it is only 8 percent. Before the Japanese bubble burst, 8 of the top 10 companies by value were Japanese. Today, there is not a single Japanese company in the top 10.

Japanese Government: Spending Money Like There Is No Tomorrow

It too often seems that whenever governments are confronted with a problem, they pretend it doesn’t exist. The Japanese bureaucracy’s first attempts to deal with the collapse involved quick fixes coping with the symptoms, rather than correcting structural problems. At first, the government ordered public-sector financial institutions to buy stocks to keep stock prices up, but this failed. The banking system suffered severe losses from loans used to buy property, but the bank tried to pretend these losses had not occurred. Employees were paid with unsold company inventory.

To cushion the blow of the downturn, the central Japanese government spent insane amounts of money building bridges to nowhere and on other public works projects with no ability to increase productivity in the real economy.

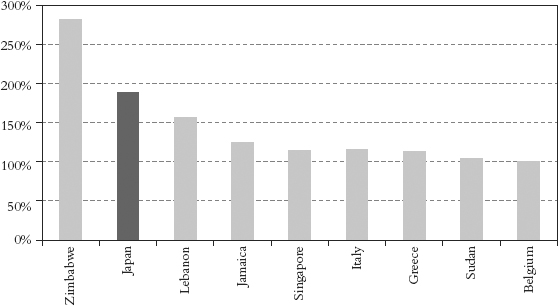

Japan started out as a healthy, dynamic economy. Today, Japan has public debt of almost 200 percent of total GDP. It is running out of its ability to use captive domestic savings to maintain or increase this level of debt. The figure is even worse if you look at Japanese debt as a percentage of private GDP. This is already at almost 240 percent.

Japan’s debt levels are now at levels seen historically only in hyperinflationary countries. Either Japan will right itself soon through political reform, or it will be the prime candidate in the world for hyperinflation. Japan is now in the company of Zimbabwe, Lebanon, Jamaica, Sudan, and Egypt in the high government debt-to-GDP stakes, as Figure 12.1 shows.

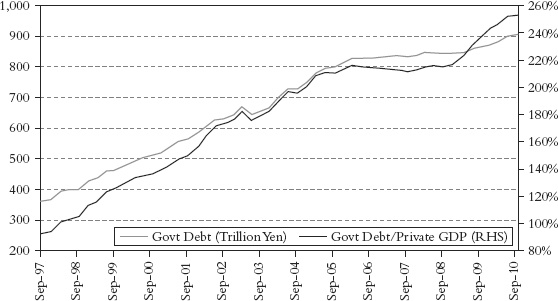

As you can see from Figure 12.2, the level is even worse if you look at the government debt to private GDP. After all, it is the private sector that will need to generate the revenue for taxes to pay down the public debt.

Figure 12.2 Japan: Government Debt and Private GDP (Nominal)

Source: Japan Ministry of Finance, Variant Perception.

Most analysts are complacent. So far, increases in Japanese government bond (JGB) issuance has not necessarily led to any rises in Japanese long-term yields, due to (a) abundant domestic savings, (b) strong home bias among Japanese investors, and (c) contained inflation expectations. Any of these could change very quickly.

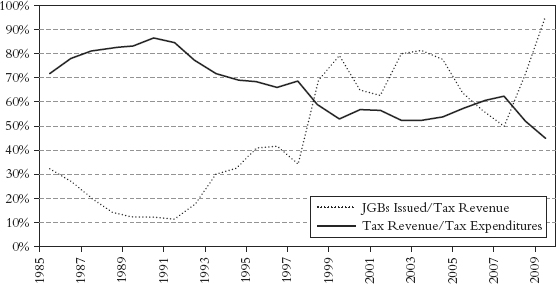

Japan’s debt is more than 12 years of general account tax revenues, and within a year, it will be closer to 15. It would take half a generation of Japanese taxes to pay down the debt. This ratio is twice as high as the next highest in history, Britain, following World War II. With the current recession, Japan’s FY2010 budget will be the first in the postwar period where revenues from debt (JGB issuance) will exceed tax revenues (Figure 12.3). This situation is unprecedented.

Figure 12.3 Tax Revenue, Expenditure, and JGBs Issued

Source: Japan Ministry of Finance, Variant Perception.

The most extraordinary thing about Japan, though, is that in 2009, the government had to borrow almost half of what it spent. As Figure 12.4 shows, tax revenue as a percentage of all expenditures is at all time lows, and government borrowing is about to exceed tax collections. The situation is not sustainable. As the great economist Herbert Stein once said, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

Figure 12.4 JGB Taxes, Expenditures, and JGBs Issued

Source: Japan Ministry of Finance, Variant Perception.

The massive amount of JGB issuance has been extremely harmful to Japan. While fiscal stimulus can help replace private demand in a downturn, government debt has completely dominated and crowded out almost the entire Japanese bond market. (See Figure 12.5.) There is the very real danger that we could eventually see similar outcomes in the United States and Europe.

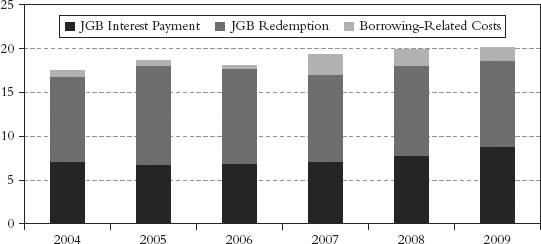

Half of all spending on debt is to service interest, as you can see from Figure 12.6. Furthermore, an increase of 100 basis points in the cost of Japanese debt would eat up a full 10 percent of the entire tax revenue. If you look at Japan that way, you can start to see why any increase in bond yields for JGBs would be so catastrophic. Paradoxically, this may be why the Japanese government prefers deflation. Any increase in inflation expectations would blow up the budget! This means they have an incentive to deflate to keep the game going. What an upside-down world. This means that all the smart hedge fund managers shorting the yen may have to wait a very long time to win.

Figure 12.6 Changes in Government Debt-Related Expenses (trillions of JPY)

Source: Japan Ministry of Finance, Variant Perception.

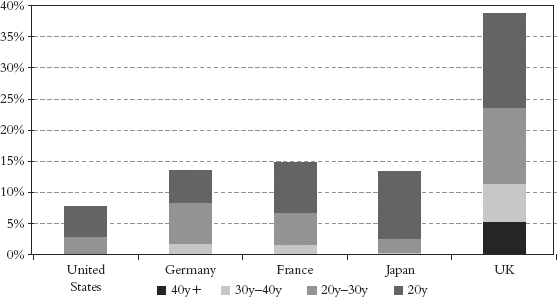

Almost all the debt is of very short maturities, so rollover risk and higher interest rates are a very real danger. Of the G5 countries, only the United States has fewer long-term bonds as a total proportion of debt issued, as Figure 12.7 shows.

Figure 12.7 Long-Term Bonds as Percentage of All Outstanding Debt

Source: Japan Ministry of Finance, Variant Perception.

All bubbles burst when financing becomes an issue. The Japanese bond market will, in the not too distant future, face a fiscal crisis that will require either draconian tax increases and spending cuts that would be extremely socially divisive or the decision to monetize its own debt, which, as we pointed out earlier, is default by another name. The first option implies a massive economic contraction, given that Japanese domestic consumption is extremely weak, and the second implies an inflationary holocaust. As we wrote before, most countries have bad choices and worse choices. Japan has only worse choices.

Japan has survived so far because foreigners don’t buy Japanese bonds. Through savings and insurance companies that are directly or indirectly controlled by the state, 94 percent of all JGBs have been bought by the Japanese.

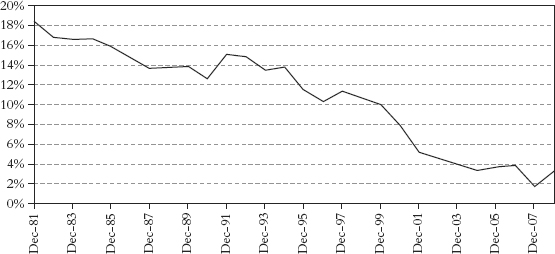

Optimists point to a large pool of Japanese savings. However, that savings pool is already invested in JGBs, so it isn’t the stock of savings that matters, but the flow. The flow has been steadily decreasing. Japanese savings rates are now approaching the low that we saw in U.S. savings rates just a few years ago. And this is not due to the Japanese somehow becoming profligate Americans but almost entirely due to demographic necessity.

The three largest holders of JGBs are Japan Post Bank, Japan Post Insurance, and Government Pension Investment Fund (GPIF). Prior to the 2001 Fiscal Investment and Loan Plan (FILP) reform, postal savings and pension reserves were required to be deposited at the Fiscal Loan Fund. As part of the reform, the compulsory deposits were discontinued, and existing deposits and interest on deposits were to be sequentially returned. From 2001 to 2009, Japan Post Bank and GPIF used those returned deposits to buy JGBs, and those deposits are now almost completely liquidated. Japan Post Insurance will soon not be a likely buyer because insurance reserves have been on a steady decline, given Japan’s sad demographics, and their year-over-year JGB holdings growth is almost 0 percent. Banks have been filling the void, but they don’t have a ton of additional capacity, given Basel 2 interest rate risk guidelines.1

Given the lack of internal demand, Japan will be forced to finance their issuance in international markets for really the first time. It’s not going to be pretty. We doubt that any of our readers will want to buy a 10-year Japanese bond for 1 percent interest. If rates went to just the OECD average, interest rates could triple. Does anyone think Japan will get rates lower than Germany, which is at 2.5 percent as we write? When rates start to rise, interest expense is going to consume a bigger and bigger portion of tax revenues. Then comes endgame. (See Figure 12.8.)

It is highly unlikely that the savings rate will increase much from here. An aging population dictates that Japanese savings rates will go down, not up. Literally, Japan is a dying country, as their population is now shrinking each year. Economics 101 dictates that savings rates conform to the life cycle savings hypothesis. You spend when you’re young, you save when you get older, and then when you get much older, you spend all the money you’ve saved in your lifetime. Now the Japanese are getting really old, and they’re about to start drawing down their savings. The savings rate will go negative.

In fact, as Figure 12.9 shows, Japan’s dependency ratio is now approaching 100. The dependency ratio is percentage of retired people supported by working people. Very soon, Japan will have more retired people than working people, and savings rates will continue to be drawn down.

Figure 12.9 Japan Projected Dependency Ratio

Source: George Magnus, “Demographics Are Destiny, Deflation Isn’t (or Needn’t Be),” UBS Investment Research, Economic Insights—By George, July 14, 2010.

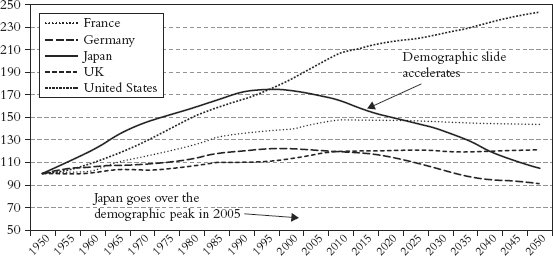

The process of Japanese demographic decline has been ongoing, and as Figure 12.10 shows, Japan is really the worst of the developed countries in terms of its decline. The United States, fortunately, has much a brighter demographic profile in comparison. Through immigration and higher birth rates, the U.S. dependency ratio will deteriorate much more slowly.

Figure 12.10 Japan’s Demographic Decline Started in Early 2000s (rebased working-age population)

Source: Societe Generale, “Popular Delusions: A Global Fiasco Is Brewing in Japan,” January 12, 2010, UN.

The percentage of households in Japan with either one person or a couple older than 65 has shot up recently. In 2005, it was 17 percent; in 2010, it is 20 percent. Twenty percent sounds low, so let’s put it another way. One in five households has an old person to look after. The demographics show that by 2015 that will rise to 23 percent and by 2020 to 25 percent. These are statistics taken from the Japanese National Institute of Population and Social Security Research, so we take the current figures and the projections as gospel. There is no country in the world with similar numbers.

A major debt and currency crisis in Japan is a case of when, not if. Forecasting when it might happen, though, is difficult. We can’t remember who said it, but the old line is true. “You can’t call yourself a real macro trader until you have lost money shorting Japanese bonds.” But when the crisis of confidence in Japanese bonds happens, it is likely to be swift, and the lucky traders who are short will become legends.

The realization that crises happen suddenly and unexpectedly is not lost on Japanese politicians. Recently Prime Minister Naoto Kan stated, “Our public finances have become the worst of any developed country. Like the confusion in the Eurozone triggered by Greece, there is a risk of collapse if we leave the increase of the public debt untouched and then lose the trust of the bond markets.”1

Japan has two options. Either it engages in extremely painful contraction of government spending, or it prints money and gets rid of the deficit via monetization. There is simply no way to pay back Japanese debts. Japan’s government is running one of the largest structural budget deficits in the world at more than 7.2 percent of GDP every year until at least 2015, according to IMF calculations. By that stage, Japan will be in the range of 230 percent debt-to-GDP ratio. Cutting the deficit significantly will be extremely difficult. Governments typically print money rather than doom the economy to a severe recession or a depression induced by economic contraction. When this happens, the yen is likely to fall dramatically in value, Japanese interest rates will go up, and Japanese bonds will sell off.

Such an abrupt change for Japan would be nothing new. Japan has a history of making 180-degree turns. In 1868, during the Meiji Restoration, Japan went from being an inward-looking country to a rising economic and military power. In the 1950s, under the Yoshida doctrine, Japan abandoned militarism and instead embraced pacifism. Both of these moments marked a dramatic turn in Japanese society. Even in 1990, after the bubble burst, Japan turned overnight from high consumption and ostentation to frugality and sobriety. What will happen if Japan makes a 180-degree turn, and Japanese savers decide to abandon the yen and Japanese government bonds?

Can we hear a bid for 100 yen to the dollar? 125? 150? 200? 250? 300? It seems unthinkable now, but it is quite possible unless the Japanese willingly embrace a contractionary, severely deflationary depression. Not a good set of choices.

We have said before that Japan is a bug in search of a windshield. The only question is when the bug will be crushed. But it does have consequences for the rest of the world. Japan matters. Japan matters a lot. Not only is it the third largest economy in the world (depending on how you measure size) but also it is a major export power.

What happens if the yen starts to lose value? What happens when you can buy a Honda, Toyota, or Lexus cheaper than you can buy a Kia or a Hyundai? Or any of a number of European cars? Now take that same analogy and apply it to scores of industries that compete with Asia, the United States, and Europe. How does Korea deal with a real loss of competitiveness? In the past, they have devalued their currency. But can they really keep up with a hyperinflating Japan? And that goes for all of their neighbors, not to mention Germany and the emerging market countries.

Yes, the cost of Japanese inputs (like steel) go up, but not their labor or engineering or the infrastructure and factories they already have. For a while, in the early stages of endgame, it is a very dicey atmosphere in world trade and currency markets.

Then, what if you are Mrs. Watanabe and the cost of everything you buy from overseas is going up rapidly? And you are on a fixed income? Your savings are not inflation indexed. First, you end up buying less. But you also figure out (because the Mrs. Watanabes of the world are very smart and currency savvy) you need to move your savings into other currencies. And since the Japanese are serious currency traders from their homes, they can do it with a click of a mouse. So there is even more pressure on the yen.

Yes, we know that the Japanese have huge hoards of foreign currencies, especially dollars. But that is not their salvation as they spend yen at home.

Once they start down the endgame path, it is difficult to get off it. It goes back to our chapter on This Time Is Different. It is a Bang! moment. And because it is Japan, it is a BIG BANG! moment.

1Many thanks to Matt Klein of Hudson Advisers for pointing this out.