1

Intimate and Momentous

Welcome back. The place where you just took your walk? Let us call that your dooryard. Its dimensions are provisional. You can enlarge it or shrink it later, as you see fit.

It is here, in your dooryard, that climate is changing. Has been changing for quite some time. Will continue to change, almost certainly at faster rates.

Such a homely term, though, “dooryard.” It is still in use today in some places to describe a patch of the outdoors where the business of human work and play, in and out of doors, transacts with the natural, the world over which we assume we have little control. Etymologically, the word traces to New England, generally, and Maine specifically. If you’ve read some Walt Whitman, the nineteenth-century poet who celebrated the United States as no other, you might recall that in his elegy to Abraham Lincoln, “When Last the Lilacs in the Door-yard Bloomed,” the word is hyphenated. That’s fine. Whitman was from away, a New Yorker. But: dooryard. In designating a kind of place, the specific meaning of the word draws a contradistinction to the front yard (a space meant to impress society) and the barnyard (a place for working with animals).

The dooryard is close in, a place for work but also for exchange. It’s where the kitchen garden might be, full of herbs and simple greens, as well as a few varieties of posies. But it’s also full of insects and is a favored place for cats or, if there are no cats, then other creatures that make their livings by living as near to human habitations as they can—mice, for example. Or voles.

I have had a dooryard or two, but before I describe them, let me show you another. I’ve ventured there a couple of times, and I’ve encouraged students to go alone, or with a friend or two. I went with friends myself, and that was nice, but on my first visit, I went there alone, and that was ideal.

The space surrounding Henry David Thoreau’s cabin at Walden Pond in the years 1844–46 was all dooryard. There was no front yard, because although he had visitors at the cabin, Henry—let’s call him Henry—was unostentatious and little concerned about what visitors should find when they arrived at his door. He briefly contemplated making them sit on pumpkins, but clearly thought better of it. There were chairs in the cabin, three chairs altogether. There was also no barnyard, since he kept no animals and there was no barn—just a woodshed, which is dooryard architecture.

A visitor today knows right where the cabin stood and just where Henry placed his door, thanks to some keen archaeological work undertaken decades ago. Obelisks and graceful chains mark the cabin’s walls. Using a dose of imagination, you can walk around the cabin. Or you can go inside, turn around, and see very much what Henry saw when he opened his door and peered through his dooryard.

I almost wrote “past his dooryard,” but that would have been wrong. For the two years that he lived at Walden Pond, the whole landscape was his dooryard—the trees, the slope leading down to the pond, the pond itself. It stopped at the railroad tracks. Where the Fitchburg train passed, that was another place.

I stood there one November day, alone, when the sky was overcast in low clouds and the calls of crows echoed through trees, which had recently shed their leaves. Being a historian, and an academic one at that, generally unsentimental of mind, I was surprised by the thoughts I had as I gazed out through the trees and across the pond. Here I was in this place, this hallowed place. Not far from here, no more than three or four miles away, a handful of men had the moxie to begin a war of independence. And they succeeded in winning their freedom and freedom for generations that followed.

Becoming and then being free, what did they do with their freedom? The answer was under my feet. Here, an irascible twenty-something decided to see what life, shed of entailments, might be. Later, he would report his findings to the world in Walden; or, Life in the Woods.

Walden began life as a book about freedom, but it wandered off into a description of the woods themselves, and of the lives that filled the woods, more than about Henry’s life. While there, Henry began a lifetime habit of noticing and making notes about first appearances—the first appearances of flowers, of leaves, of birds.

From his attentiveness, Henry came to believe that November was a separate season, unlike any other. Just November. That was what I experienced in Henry’s dooryard: freedom, and the season of November.

Or did I? Beginning in 2002, Richard B. Primack, a botanist at Boston University who had previously ventured to places like Borneo to collect field observations, turned his attention to Walden Pond and to Thoreau’s records of plants and animals—mostly plants. Primack discovered that many of the plants in Thoreau’s notes could no longer be found there. Just as important, other plants still growing in Concord flowered at different times from those that Henry observed. Primack concluded that Walden—Henry’s dooryard—was warming.

Thoughts of Walden bring to mind my own dooryard, for I once had the luxury of a dooryard when I relocated to a very small town in Maine (where to call the town a “village” would seem an affectation). I was nearing the age that Henry had been when he built and moved into his cabin, and my move was perhaps proportionally equivalent to his. Concord is to Walden Pond as Boston is to rural Maine. I had been born in Portland twenty-five years earlier, and though I only recalled vacations there with family, I kept a romanticized vision of it in my head, aided at that time by the many letters and essays of E. B. White, whose book of correspondence had been published just the year before.

Whether close to the coast or inland, houses in Maine that date from the 1800s once supported subsistence agriculture, at least, if not full-blown agricultural output. The one I rented for my first year there was more the former than the latter, and it saw me through four full seasons. The house itself was what is known as a two-story colonial. It had an ell, with a large kitchen below and a bedroom above. Unlike many of the houses in town, the ell was the end of the line. There were no additional connected buildings. By tradition, many houses (both in town on a few acres or less, as this house was, and farther out on the blue highways and back roads) were connected: big house, little house, back house, barn. But even without a connecting back house (the little house was the ell), the property had a full set of yards—front, barn (for there was a barn), and dooryard.

I moved in at the height of winter, within a month of meeting the inspiration and model for this adventure, E. B. White, author of Charlotte’s Web and for several decades the voice of the New Yorker magazine, at his home in North Brooklin, Maine. I had knocked on his door late on a January afternoon; he famously developed a strong dislike for this sort of intrusion, but I have a gracious reply to a letter of thanks I wrote him, and I later came to make a distinction between summer visitors and winter visitors. Perhaps he did, too.

My new home felt like the edge of a Great American Wilderness. It certainly was different from any place I had lived before. One local fact that I had difficulty ignoring, for the first month or two anyway, was that the elderly woman who would have been my next-door neighbor had been murdered in her home the week before I rented. My first visitor was a detective investigating the case (I soon learned that many of the townspeople seemed to know who did it; there was never an arrest). He assured me I had little to be concerned about.

I was essentially faced with a choice: live in E. B. White’s Maine or live in Stephen King’s. I chose the former. White’s essays were full of pointers on how to succeed at rural life down east. Like other essayists before and since, White seemed fond of winter and winter’s rhythms. Reading One Man’s Meat gave me a vivid and sensuous image of something as mundane as a late evening visit to the barn, to check on the animals. I did not yet have farm animals, but I paid visits to the barn at night as though I did. I sent for seed catalogs and purchased the minimum gear needed for raising chickens. In the meantime, doing without a car (and resenting the need for one, to which I would eventually capitulate) my world was circumscribed by the distance I could walk daily on the sides of winter roads.

Figure 1.1. My dooryard at sugaring time.

The house was “in town,” where the houses were densely configured on lots of about an acre each. There was a general store (groceries, hardware, widgets), a gas station, and another smaller store that had only recently added refrigeration. This was known as Dot’s, although Dot hadn’t owned it for some time. After a spell, I would pay my bill at Dot’s by baking apple pies for sale; that first year I ran my bill up and paid it down as best I could. I was able to make my living, or nearly so, doing freelance work for publishers in Boston, and so needed only to walk to the post office, the general store, and Dot’s.

Snow fell regularly that winter and was cleared by plow trucks that absorbed much of the town’s budget. Behind Dot’s and beyond the bridge leading into town there was a smelt camp—a grouping of twenty or so small shacks that had been set out on the river ice so that fisherpersons could sit inside, warmed by a small woodstove, and fish for the little fish. At night, the space between shacks was lit by a string of electric lights. With these, the smelt camp gave the town a sense of something happening, possibly even some excitement, but as White had said nothing about smelt fishing, I put off a visit to some future time.

Figure 1.2. The geographical extent of my dooryard in Maine, showing places I mention in the text. It was not a big place.

I did order seeds and eighteen chicks. I also bought taps for the maple trees in my dooryard. The chicks came first, and on that day, the post office was filled with the sounds of chicks in piles of cartons. I raised the chicks successfully, but a marauding member of the weasel family called a fisher, for which I was ill-prepared, killed all but two of the resulting hens. I slaughtered, plucked, and ate one chicken. The other provided brown eggs for a time.

The poultry aspect of my adventure didn’t go especially well, and I tell of it only out of the wish to establish myself as a reliable narrator. But the maple syruping part was a success—in my eyes at least. My dooryard was lined with maples, and when conditions were just right—warmer temperatures in the morning, freezing at night—I drilled and tapped the trees and hung gallon milk containers that I’d collected for the purpose. These were unsightly but common; galvanized pails with little rooflike covers were a rich man’s decoration. I gathered and evaporated enough sap to make maple syrup for my own consumption for a year, plus some maple sugar candies. I used up a lot of propane to do it.

As days grew longer, and the snow thinner, the sap stopped flowing. The smelt shacks had already come off the river. The river being tidal (a necessary condition for smelt), the ice groaned for several weeks as it rose and fell twice daily with the tide. It was so cold that year that the Coast Guard came up the Kennebec River with an icebreaker to get things moving. Crocuses called for a coming of spring—in Maine, the coming of spring lasted from early April until sometime in June—followed by the appearance of forsythia. The spring peepers, a type of aptly named chorus frog, came and went. I knew it was summer when the side yard (another oddity of this house) was suddenly filled with day lilies in bloom. Summer, hardly my favorite of the seasons to begin with, was made worse owing to the overabundance of freelance work passed on to me by publishers, but it fortunately passed on to fall in short order. None of seeds I ordered had gotten into the ground.

Fall brought longing. Some people graduate from high school or college and never look back. Others ache to revisit texts and notebooks as soon as the first leaves change. I am the latter type. I eventually resolved that seasonal nostalgia for campus life by remaking myself as a college professor. That year, though, I delved into autumn chores. My neighbor across the street was a local history buff and organizer of the historical society, which met in October around a cider press. We made cider and started talking about preparations for the winter to come. Would we all have enough firewood to “spring out”?

As these were the “energy crisis” years (Jimmy Carter was president and Michael Dukakis, governor of that state to the south, appeared on television appropriately dressed for his lowered thermostat in a cardigan sweater), we all thought and talked about energy the way others talked about real estate a few years later. My rent that first year, reasonable even then at $275 a month, was eclipsed by the cost of heating oil in such a large, uninsulated house. By midwinter the following year, I had moved to more efficient lodgings.

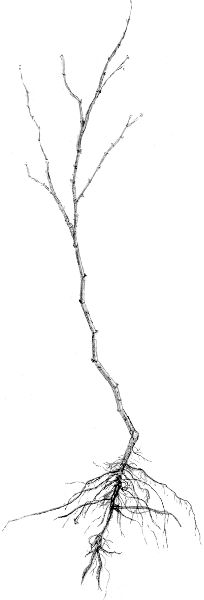

I was learning. And I was not and had never aspired to the role of back-to-the-lander. After a period of atonement in a tiny apartment closer to Dot’s, I lived for seven years as a tenant on an apple farm several miles from the center of town. I planted a few of the five hundred apple trees on the property and took time to draw one of the bare root trees before I put it into the ground. But that first year, thanks to the absence of an automobile through the better part of it, I was more than usually attentive to the seasons.

Figure 1.3. A very youthful apple tree, ready to be planted.

Seasons are a fact of life, and few things in life are experienced with greater intimacy.

Good records of the sort that would be helpful are the core of phenology, the study of seasonal change. (I have heard it pronounced with a long e and a short one. Either is probably correct.) Phenology is best described as a minor science that has been practiced by major figures, including Thomas Jefferson, Henry David Thoreau, and Aldo Leopold. “Data” of the phenological kind also fill the diaries and letters of American men and especially women over the past two hundred years. As agricultural colleges developed in the post–Civil War years, phenology was sometimes offered as a course of instruction. Today’s climate scientists have made use of these records as a way of identifying consequences of climate change.

To practice phenology means, specifically, noticing and then recording events that occur seasonally each year: the first buds of maple leaves, the first robin in the yard, the day that fireflies appear on a summer evening. Weather events are also of phenological interest. When was the final frost of the spring? And the first in the fall? How many days did cumulus clouds appear in the sky? How often did the tornado sirens sound?

Let us return to that list I asked you to make in the prologue. It is a rough draft of a list of potentially endangered entities. Your endangered entities list. Some of those entities are species. But if you were inclusive enough, some of your list items are other: rocks, perhaps, or the webs of spiders (the webs, unlike the spiders themselves, are not species). They are endangered because of climate change. On a walk ten years hence, or twenty or thirty, a list made in the same place, on the same day of the year, will be different. How it will differ is difficult to say. And that is much the point of this book.

Your dooryard may differ from what I just described in details small and large, and I have stretched and refashioned the term “dooryard” to mean something more than the Maine dooryard. When I write “dooryard,” I am referring to your neighborhood, your environs, your surrounds.

As climate changes in an acute fashion—and it is changing, acutely—the world is also changing, your dooryard with it. The change is acute because it is in response to specific human actions that have increased by orders of magnitude over the past two hundred years, a very short time in the history of the planet. I will not try to convince you that this is so. By now, it is obvious to anyone who is paying attention. Anthropogenic climate change is an undeniable fact, albeit a noisy one. And it is so clearly the case, the fact of the matter, that if you don’t believe it, you are practicing what the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce called “the method of tenacity.” There is almost nothing I can say that will change your mind, and so I will not try.

That last was rhetorical. You already know that the world’s climates are changing, you know why they are changing, and you have a sense of what needs to be done to contain the variety of catastrophes that we face. None of that is the subject of this book. Instead, the pages that follow are about how to live in and how to know a changing world. Because, have no doubt: changes are unfolding.

What those changes will be, it is difficult to say. In the broader sense, ice will go out of the Arctic Ocean, in the summer at least, and sea-lanes will open up. Cities—new Chicagos—will be built on the north coasts of Canada, Alaska, and Siberia. Polar bears, those that survive, will be drawn to the trash heaps of those cities. There will be famines in places that once were better watered. Coastal areas, working seaports and city parks, will vanish, to be replaced by new versions of their old selves, in new places.

In their zest to alert the rest of the world to the alarming fact of climate change, scientists have made some choices concerning what to talk about in order to get our attention. Some of those choices have caused confusion. But most of the confusion about climate change is intentional, as Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway demonstrate in Merchants of Doubt: How a Handful of Scientists Obscured the Truth on Issues from Tobacco Smoke to Global Warming. And most of that manufactured confusion counts as malevolence.

Then, there is honest confusion. “Climate change” and “global warming”: even without the handful of scientists that Oreskes and Conway talk about, the two phrases that designate this set of phenomena each contain one or more red herrings—words and concepts that scientists use in a slightly different way from the way laypeople use them. First: climate change. “Climate” is not a synonym for “weather.” Weather is palpable: it’s hot or cold. There are clouds or there is blue sky. It’s raining, snowing, or not. Climate is different. Climate is an abstraction. We don’t experience climate, in the way that scientists use the term. Instead, climate is a description of a number of factors, temperature among them, over decades. Thirty years is a customary measure. Climate is inferred from records kept over generations. It’s not something to be judged from a given day’s weather, or even weather in a given year.

If one cannot find climate in weather, where does one look? The simple answer is that climate is best seen in plants—botany—and change is best seen through slow, patient phenological observation. We will come back to both botany and observation.

If the disjunction between climate and today’s weather is not bad enough, there is also the problem of “climate” in the singular. The earth possesses not a single climate, but many climates, each interlinked to others in complex ways. The same difficulty is found in the word “global.” Climate scientists have devised ways to measure a global mean temperature, but it’s not something that any one person experiences as such.

And that brings us to “warming,” which implies temperature. To a nonscientist, temperature is primarily a measure of comfort whereas for a scientist it is a measure of energy in a system. Simply put, if you think of the earth as a system made up of systems, there are at any given time a large number of adjustments and adaptations to changing conditions. If the change in conditions is gradual, then the adjustments and adaptations are gradual as well. But when the change in conditions is rapid, the adjustments and adaptations are also rapid. Increase the energy in the system, and you will see a change in conditions.

Some time ago I bought a Volkswagen bus that had been modified to improve its performance. Unfortunately for me, the modification was illegal. In order to register the vehicle, I had to procure and install all of the original components that were standard in the year the vehicle was produced. I did so—it was something of an ordeal—and I returned the engine to its original configuration, or nearly so. An error in the mix of parts allowed air to leak into the system, causing what mechanics call “lean running.” In time, lean running led to the demise of the engine, as heat from combustion in one cylinder led to a molten hole through one piston.

This happened on long-distance journey, as I was driving up an escarpment that rose from sea level to five thousand feet in a matter of a few miles. Would it have happened on level ground? I’ll never know. But here’s what happened. The hole in the piston allowed the combustion in that cylinder to force most of the oil out of the engine and onto all the surfaces in the engine compartment (this is known to mechanics as “blow by”). In a matter of seconds, this would have starved the bearing surfaces on the crankshaft of oil. But before that could happen, a light came on and I shut down the engine.

Is this a good metaphor for climate change? It is and it isn’t. On one hand, my engine, like Earth, is a system made of systems. On the other, Earth is many times, indeed many magnitudes of order, more complex. Earth is not equipped with an oil light or with a driver who is committed to preventing complete catastrophe. But otherwise, for this discussion, the metaphor is apt.

There are predictable things that will happen, are in fact occurring, and ought to substitute for an oil light. Ice on land is melting and flowing into the oceans, raising sea levels. Ice that has been secure on land is slipping into the oceans and is raising sea levels with the potential to do great harm. At the same time, as the oceans absorb heat, they increase in volume, also raising sea levels. And the warming oceans are becoming more acidic. These consequences are ongoing, and the processes behind them are somewhat predictable.

But sea-level rise, at current rates, is not simply like filling a bathtub. Today’s shorelines have adjusted—and shore-related biology has adapted—to a relatively stable sea level. Change the sea level and shorelines change (adjust and adapt) in ways that aren’t entirely predictable. And I’ve said nothing yet about the increasing frequency and intensity of storms.

This is just one example among countless examples. We do not know enough about the world, yet, to predict everything. There are many changes that we will just have to learn about as they happen, and this will be true for our children and our children’s children. The consequences of climate change, in their great number, are unlikely to be all of a kind, and few of them are knowable in advance. They are likely to be uneven—lumpy is a fine word—in character.

Of the natural sciences that help us make sense of climate change and its consequences, ecology—the study of the relations between organisms and their environment, the area most likely to be affected by change—is among the least developed. Offering no weapons for waging and winning wars, little in the way of pharmaceutical interest, no roadmap for finding oil or gas, ecology has had something of the status of a Dickensian stepchild among the sciences, even as “the ecology” became a synonym for “the environment.” There is much that ecologists and their practical fellow travelers, conservation biologists, know. But there is much that they do not know.

They are about to learn a lot, if they can gather the immense harvest of data that is potentially forthcoming. Let us call climate change, provisionally, an experiment of an inadvertent sort: a grand experiment. Disturbances in otherwise stable systems provide opportunities for understanding. Francis Bacon, a proponent of scientific inquiry in the early decades of the Scientific Revolution, suggested as long ago as 1620 that “the nature of things betrays itself more readily under the vexations of art than in its natural freedom.” What greater “vexations of art” could there be than in rapidly ensuing changes in climates?

We stand to learn a lot. But is it ethical to gain—in this case, to gain knowledge—from what many would argue is an injustice? This is a hard question, and I cannot fully answer it here. But I can suggest that much that we learn will aid in mitigating additional destruction.

The best thing that could happen, today or next week or next year, would be to reach agreements, intranationally and internationally, to cut carbon emissions, to roll them back, and to begin mending the damage done to the planet, especially that of recent decades. This may yet happen, and that is what I, and what I can imagine you, hope for. As of this writing, however, it does not seem likely in the short run.

In the meantime, it seems as though it might feel morally wrong to describe cumulus clouds or count fireflies when whole nations pass below sea level. In doing so, we seem to accept climate change. Is acceptance, in this case, causative? In some sense it is, particularly if acceptance is our only response.

The range of actions that can be taken to slow climate change, and even to reverse its course, is great, and these actions fall into two primary categories: mitigation and adaptation. In the area of mitigation, individual and voluntary actions to reduce one’s carbon footprint are surely worthwhile and serve as signs to others. Political action is more important to mitigation, at present. Adaptations are inevitable, even when the need for them is met with reluctance. But being aware, even while mitigating and adapting so as to ward off harm, are not mutually exclusive actions.

And so it is helpful to think of our relationship to nature in two distinct ways. We should think of human life and human action as part of nature and, yet, as distinct from and in some degree opposed to nature—both of these, at the same time. Philosophers know the second of these attitudes as dualism. All human actions, from this point of view, are unnatural. The idea of dualism is sometimes called the natural attitude, not because it is an instinct but because it is deeply embedded in Western culture, especially American cultural traditions. Its source is the monotheistic traditions of the world’s major Western religions, according to which humans are accorded a special place in creation by God—dominion, as one biblical passage put it.

As the historian William Cronon has argued in his finely sketched essay “The Trouble with Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature,” this set of ideas causes us to value different parts of the natural world with different levels of enthusiasm, sympathy, and awareness. To Cronon and others who critique the dualistic notions, humans are every bit as natural as anything else. We are animals, albeit crafty animals.

Does this absolve humankind from responsibility for climate change? For extinctions? For a path of destruction that is unfolding even now? Is anthropogenic climate change logically, then, simply natural climate change? These are difficult questions—revealing in some ways and concealing in others. If we choose, on the whole, to let climate change unfold, it will. But the Anthropocene, as some have taken to calling this geological epoch, could just as easily be a time when we crafty animals recognize the damage we are doing and reverse course.

The dualism/antidualism notion does not, in itself, solve problems. But it is useful for thinking about how to see the world from our dooryards, to which we again return.

Today, in New England, where I had my first dooryard experience, syruping occurs later and is threatened by climate change; the sugar maples produce sap with lower concentrations of sugar and are disappearing from parts of their former range. Smelt fishing, too, seems to be off. In some years, the ice isn’t as thick for as many weeks as it was in the past, and recently, when it was, the smelt weren’t there in their customary numbers. Fall arrives later than it did. Careful records of the comings and passings of seasons over the decades would provide a clearer picture of how the climate had changed, had I kept them. I possess memories, some of them true and some romanced, but little in the way of data.

Figure 1.4. The smelt camp operated long into every evening, when fishers would take shelter in the small huts on river ice. The number of weeks—or days—when the ice is thick enough for the camp has shortened, and the smelt come at different times from what people remember from the past.

In the chapters that follow, we will look in detail at phenology, its history and practitioners, and at the relationships that obtain between the sun and our tilted, orbiting planet. We will examine the drivers behind climate, the ways that climates change, and the forms that landscapes take in response to climatic factors, stable and changing. For those who appreciate no more than an exemplar and a gentle push, that may be enough. The rest of us might like a little more guidance, and this book will provide it: how to establish baselines in photographs, maps, and lists. (I will advocate “kite aerial photography” and rephotography as ways of capturing baselines.) There will be guidance on how to make useful observations of weather, plants, and animals, along with explanations of how different species of animal and plant become adjusted to seasonal change and climatic equilibriums.

If you find all of this bracing, I will recommend that you practice citizen science, keeping careful records in a form that can be used by scientists and perused by other citizen scientists. If you would rather keep your own counsel, it is fine to engage phenology as a participant observer.

Nothing in the pages to follow is designed to demonstrate that our global climate is warming. That has already been amply demonstrated, and it is perverse to suppose otherwise. Neither does what follows provide a plan for turning back the clock, or turning down the thermostat. Rather, what lies ahead is a plan—partial in its scope, for there will be much else to do—for living in a time of warming climate. Climate warming is not something to be wished for, not something to be encouraged but, rather, being fact, something to acknowledge and to face squarely.

We learn in our science classes that scientists make observations. They also develop hypotheses, devise and execute experiments, test theories—so goes the litany of scientific method. But let us pause to contemplate those observations. An observation must have about it the characteristics of the here and now. It cannot be speculative, reaching somehow for the future, for that would taint both the process and the outcome. With this presentness, scientists share some part of the spiritual experience of one who is mindful, someone who is attuned to what is here, and now.

This is true no less of phenological observation than it is of any other pursuit in science. Each observation I make—of grasshoppers or bluebirds, of small pools of water from yesterday’s rain—binds me intimately to my dooryard and to the present, even as climate change grinds along, like a steamroller on an endless road, momentous in all its implications. My presentness, and yours, releases us temporarily from the incessant, and often noisy, directionality of climate change.