8

Feathers and Phenophases

It was a privilege, the first time I saw them. It’s a privilege at any time, really. But that’s what I thought that first time. A privilege. As indeed it was, even though my sightings were far from unusual. There were six of them altogether, one every thirty seconds or so, gliding a thousand or so below my footing on the south rim of the Grand Canyon. I recalled the way that Roger Tory Peterson described them decades before. They looked to him like bombers from the era of the Second World War—B-17s and B-24s, massive aircraft that lumbered along overhead a lifetime ago in places not unlike condor habitat. I looked at my companion, who showed in her eyes that she was in as much awe as I was; although, being younger, she didn’t know quite as well as I did what a miracle we were witnessing. Six California condors, riding thermals, going about their business as though their species hadn’t been snatched from the precipice of extinction, preserved, bred, and returned to habitat that could support them. In the few short years since that afternoon I’ve frequently seen condors in the canyon, but I do not yet take them for granted. I hope I never will.

The California condor, along with peregrine falcons and (in the wake of Rachel Carson’s warnings in Silent Spring) bald eagles, are among a small but celebrated number of success stories, stories of bird species rescued from the fate that befell dodos, auks, passenger pigeons, and (although this last is still not certain) the ivory-billed woodpecker, all of them extinct or presumed by many to be extinct. (Hopeful lovers of bird life simply reserve judgment about the fate of the ivorybill, based on reports of a “sighting”—actually a quite credible report of the call of an ivorybill—in 2004. Many birders consider it bad form to treat the ivorybill as an extinct species.)

Set phenology aside, for just a moment. Seeing condors is worth what little effort it takes to do so, as is seeing and knowing all the birds that make their homes or pass through your dooryard. Of the plant and animal wildlife in the United States, birds have historically attracted much of the spotlight from people who love and care about nature. The National Audubon Society, named for the artist John James Audubon, is currently involved in promoting a spectrum of environmental interests. But it originally had a clear focus on the conservation of birds and bird habitat, as well as the enrichment of its members’ lives by the study of birds. It is among the oldest organizations promoting both conservation of and attention to bird life. There is more than good reason to associate the artist’s name with birds and conservation. The book Birds of America is a masterwork. There have been many times that I’ve lingered over the elephant edition of Audubon’s opus, displayed under glass in the Hawthorne-Longfellow Library at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. (It is now kept in the library’s special collections unit.) But as much as I thrill to the arts of the brush and the printing press, I am all the more thrilled by the sight of a pileated woodpecker in my dooryard, giving me just enough of a look for identification before this red-crested bird circles behind a tree.

Along with millions of others, I was drawn to watching and knowing birds by a Peterson guide, and if Roger Tory Peterson (1908–96) were alive today, I would ask him to write a foreword to this book—for more than a couple of reasons. First among them, I trace my interest in birds to his writings and to other books for which he wrote forewords. More important, Peterson would (I feel quite confident) have understood what this book is about; would have understood the problem the book addresses (climatic change, about which he would doubtless have been alarmed, for his beloved penguins in Antarctica if for no other reason); and would have supported the plea that the book makes (go outside, look at nature, see for yourself if it isn’t so, and observe what it amounts to). Peterson transformed the interest of ordinary Americans in nature, Americans like me, to be certain, and perhaps yourself, by making it relatively simple and straightforward to go outside, observe a bird, identify her based on his system of field markings on his pictures of birds, know her name, know her when you see her again. My parents had a copy of A Field Guide to the Birds, and although the first copy I bought and owned myself was among the last that he produced (the guide to Eastern birds), and was found to be a mild disappointment by many experienced birders, I still favor it over my much newer Sibley bird guide.

Peterson believed that paying attention to birds, which he and others came to call birding (not bird watching), a special kind of attention that involves not just knowing their names but watching their behavior as well, was a key to preserving nature in the United States. It’s something that he said over and over again, a sentiment that hailed from his gut rather than any specific empirical evidence.5 Before the Peterson guides, a clear bird identification required a specimen: ornithologists shot birds to be certain what they were. Peterson’s guides changed that. And while Peterson didn’t directly address phenological concerns in his life’s work, I have little doubt that he would do so today.

Figure 8.1. A pair of pygmy nuthatches. Although not endangered, large patches of their preferred habitat—the ponderosa forest of the American Southwest—may shrink in size in coming decades.

Concern for birds is older in this country than Peterson and his guides. Although the carnivorous among Americans make light of eating a few domesticated birds—chicken is on the menu of almost every fast food outlet—and dine on some water birds with perhaps more of a sense of treading on a wild place, songbirds and several other families of birds are strictly off the table and have been for more than one hundred years, along with their feathers and eggs. What was once the concern of conservationists with an ornithological bent is now a take-for-granted moral certitude. Would you munch on a bluebird, or fry up a pan of robin’s eggs? The loss of several bird species and declining numbers of many species have made birds perhaps the signature conservation interest since the rise of conservation movements in the nineteenth century and of environmentalism in the twentieth. Hats full of bird feathers came to be as unfashionable in some circles in the nineteenth century as furs are today. A concern for birds led Rachel Carson to give her seminal work on pesticides the name Silent Spring: silent spring, and no birds sing. For decades, budding conservationists have learned of the plight of the passenger pigeon, the last individual in what was once a vast population in number having died in the Cincinnati zoo. Is there an environmentalist who has not learned to compare any and all threats of environmental degradation to the “canary in the coal mine”?

Passionate birders, meanwhile, have always thought phenologically, whether they knew the word or not. In the crudest sense, most everyone knows that robins herald the arrival of spring in parts of the country. Chickadees spend the winter calling out from under their black caps into the cold air. Canada geese, flying in a V formation, point northward in spring and south in the fall. With greater knowledge of birds, watchers know when to look for the arrival of migratory birds and feel gratified, and a bit relieved, when they show themselves, more or less on schedule. Even when our attentions are drawn to other things, we notice the arrivals of birds, even if we don’t make note of precise dates. Early this past spring, when I moved from the Colorado Plateau to a small, temporary residence in the foothills of the Peninsular Range in Southern California, I noticed swallows filling the sky as soon as I stepped out of my car the day I arrived. Who could miss them? Most active near sunset each day, their guano plastered my landlord’s stuccoed home in a dappled-over layer of white. And then, on a summer day, I noticed they were gone. All of them. Not a swallow to be seen.

In this latter observation, I didn’t capture the exact timing of their departure. They may have been gone for days, or even a week or two, while my mind was on my teaching and other mundane matters. But gone they were, and I noted this in my journal, where the fact doesn’t do much to help science but does save for later reflection my sense of the space I occupy. A more precise notation of their departure and—had I moved in time to witness it—their arrival may have had some value. For phenological data about birds tell us two things. First, a phenological record provides an assessment, however small, of the condition of the environment, generally. This is especially true as our planet warms and landscapes change. The second is an assessment of the health of populations of swallows themselves.

And, as Peterson himself so often said (he wasn’t alone in this), it’s entertaining and edifying to pay attention to birds. Only two days ago, in Maine, I grew attentive as three wild turkeys raced across my path while I drove into town to do errands. They looked rather like dinosaurs. They are, perhaps, dinosaurs. Or dinosaurs, birds. The jury is still out, not so much on the taxonomic relationship between the two groups but about how we should regard this evolutionary fact. Dinosaurs! Crossing my path! But I don’t need to see dinosaurs in order to enjoy birds. I clearly recall a visit to Disneyland with family and friends, a couple of decades ago, where I had tired of the rides, the lines, and what for me was a forced front of having fun. I sat at an outdoor table in the center of things, enjoying a refreshment of some kind and marveling at the many hundreds of birds who, no fools they, assembled to take advantage of the environmental edges designed into the landscape of artifice. Birds. At Disneyland.

How are birds attuned to seasonal change and to climate? Where do you look for them, and what do you have to learn? What equipment aids the effort? And how do phenological observations and records of birds enhance your sense of your dooryard, as well as science? Most of this chapter will seem terribly basic to those who have already taken up birding, although some of the tips on specifics of record keeping and paying attention to changing nature might be welcome. For readers who have not given themselves over to the joys of birding, the chapter is a foot in the door, one that I hope leads to engagement with the wider worlds of birding, ornithology, and conservation.

The chances are good that your dooryard is a home, a breeding place for migrants, and a crossroads for birds that pass from far away to far away, going one way in autumn and the other way in springtime. There are phenological clues to climate change in all three of these.

Birds can be challenging for phenological observers. It’s easy to miss their first appearance, and easier still not to note their last stand come autumn.

Birds are usually busy doing one of three things: making more birds, going somewhere that’s good for making more birds, or staying alive long enough to do it all over again. Each of these is conditioned by seasons, especially in the temperate and polar regions of the earth. Over the course of a year, an adult bird may be devoting time and energy to migration (but this applies to migratory birds only, of course), to breeding, and to changing out their wardrobe of feathers (the annual activity known as the molt, or molting). Each of these defines a phenophase in the bird’s year. The phenophases do not overlap. Birds don’t migrate when they are engaged in reproductive chores (and joys), and they don’t molt when their time and energy are taken by the other two activities.

Figure 8.2. A mountain bluebird glides over an exotic Western landscape.

Anyone who loves maps also loves to think about bird migrations, even imagining that birds somehow carry maps tucked under some set of feathers as they make their way north across the United States in springtime or head for wintering places in the fall. Canada geese (Branta canadensis), in their precision V pattern, must have a navigator or two who has memorized the map and carries it in her head, landing—as so many migratory birds manage to do—in the same handful of acres each year.

Or maybe it’s GPS, in a bird-reader edition. Whatever it is, it amazes, as does the timing. Our Canada goose, the one with the map, seems also to have with her a companion carrying a thermometer. Together, their advance across the country in formation with other geese occurs at a steady thirty-five degrees Fahrenheit. In the 1950s, Frederick Charles Lincoln mapped the migrations of Canada geese and other birds according to isotherms—lines of equal temperature. The black-and-white warbler, he wrote, takes fifty days to cross from the winter range in Mexico and Central America to breeding grounds in the upper Mississippi and Ohio River drainages and the Great Lakes. The gray-cheeked thrush covers a similar distance in about half the time.

They follow itineraries with admirable precision. They anticipate. Birds get ready, growing restless, in many instances, as time for the migration approaches. And they bulk up for what’s to come. Throughout the winter they have accumulated fat to provide energy through the migration, especially in bird species that travel across oceans and seas.

Obvious as it seems, it’s still worth contemplating the difference between the phenophases that birds respond to and the green-up phase in plants. A plant takes its cues from one complex set of conditions and grows its leaves. For birds, variations in trip timing are the result of a more complex reading of weather patterns. In addition to the bird with the map and the one with the thermometer (I’m being facetious, of course, to say nothing of indulging in the sin of anthropomorphizing; and all the birds have these capabilities), there’s one who can read wind patterns and carries a barometer. Many birds like high-pressure air masses for their spring migrations and like to stay toward the west side of such masses or in the center. This makes sense: the clockwise airflow around high-pressure air masses speeds them on their way north, reducing the amount of energy it takes to make it from winter homes to breeding ranges. Birds avoid the opposite sets of conditions, for instance the counterclockwise winds that flow around low-pressure cells, which would impede progress and require greater expenditures of energy. But they do like the west sides of low-pressure systems for their southerly migratory flights as days shorten in late summer through autumn.

Migrations, to put a point on it, are dependent on complexities of weather. Migratory birds move to regions that give them reproductive success and then return to places that allow them to conserve energy through the winter. Changing weather patterns may spell difficulties for migrating birds, possibly tempting some to remain in their breeding range longer than is perhaps wise. My earlier focus on the difference between astronomical seasons and ecological seasons may seem, at first blush, the ravings of a pedant. I assure you that they are not. The dominant phenological cues—the events that plants and animals’ respond to out of genetic programming—are day length and temperature. There are other environmental cues, but temperature is the most important. And, as we have seen, temperatures (the environmental cue) are changing whereas the lengths of days (the astronomical cue) are not. This is certain to cause innumerable mismatches in interspecies dependencies.

Here, the value of phenological records of breeding birds is obvious. As climate changes, and with it the seasons, birds will respond in complex ways. Exact dates of migration in spring and fall provide important information about what may be happening.

Migratory birds are among the many sorts of animals (and plants) that cease reproduction in times of colder temperatures, shorter days, and scarce food resources. To put it bluntly, their gonads go south in winter whether the birds do so or not. When they return to their breeding areas, the gonads of both sexes re-form, testes in males and ovaries in females. Temperatures are a factor, but not the only factor, in testes formation. Ovary development responds to a nuanced soup of factors, such as mates, materials for nests, and habitat.

Birds pass through an annual breeding cycle in which they establish territory and mate. The female lays an egg; the egg is kept warm by one or both of the parent birds (or by some other bird or birds). The chicks hatch, are fed, and then fledge, depending on instinct and a learning style informed by grit to achieve flight. Finally, the young birds become independent and the adults breed again or call it quits (their gonads shrink back into irrelevance), depending on species and conditions. Shortening days seem to be a major determiner of the end of the breeding cycle.

The variation in how to accomplish this short list of tasks, from one species to the next, is immense. Territories become established through singing and displays. These latter, along with mating rituals, are a staple of nature videos—the dancing and strutting are potent metaphors for human sexual practices.

Territories may be roughly the same for mating and for nesting, or they may be in different places. Some shorebirds, among others, nest together densely, but rear their young in less dense territories. Birds nest in trees, under the eaves of houses, in stony ground, on beaches. An example of these last is the interior population of least terns, the smallest of the terns, a shorebird that breeds in the region of the rivers of the American interior—the area drained by the upper Mississippi, Missouri, Ohio, and Red Rivers and the Rio Grande. They nest in dense territories on sandbars, on the gravels of glacial moraines and rooftops—any place close to sources of small fish. In the fall, least terns migrate to areas around the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico.

Resembling the common tern, but smaller in size, least terns are minimalistic nest makers, crafting nothing more than hollowed-out spaces dug into sand or gravel, which the eggs and the hatched chicks resemble in color. Indeed, this camouflage determines, to some extent, the success or failure of breeding. As are many birds that are reared on the ground rather than in nests above the ground, the chicks are precocial—ready to be about their business a few days after hatching—although parent birds keep an eye on them and feed them as they grow.

It should be no surprise that, given their habitat preference, least terns are an endangered species. The number of activities that humans engage in along the shores of lakes and the banks of rivers is endless, and each one threatens nesting habitat. Changes in climatic conditions are fairly certain to bring changes to lakes, rivers, and water tables in the American interior, although concerning what changes, and with what effect on least terns, nothing is certain.

When their reproductive duties end, birds molt. Without the molt, their feathers would wear out. Changing them—letting go of the old and growing new—makes for a nearly brand new bird over the course of a year, but it requires a lot of energy. So not only do birds tend to do it when they have the energy to do so, they take their time, too—between six and twelve weeks for songbirds. That’s up to three months for a wardrobe change. The speed at which the change occurs seems to be regulated by the length of the day. Birds linger at the task when days are long and get with the program as days shorten. Since day length is independent of weather conditions in a warming environment, this provides a mismatch under conditions of climatic change, although its significance is thus far unknown. A variety of birds have yet another change of plumage in advance of breeding, one that is done to promote breeding success. And the extent of the molt, whether it is of all the feathers including those involved in flight (the primary and secondary feathers that provide the wing’s trailing aerodynamic shape, plus the tail feathers) or all but those involved in flight depends on the age of the bird. One need only think of the migratory warblers, which have one appearance in spring and quite another in fall as they pass through American’s dooryards, confounding birdwatchers’ efforts to distinguish between them. In the pre-breeding molt, there may be more concern among ornithologists, perhaps, that phenological mismatches could occur, although warming temperatures during the molt could place birds in greater jeopardy from predatory species.

For more than a century, the greatest threat to birds in the United States has been the loss of habitat, as the nation’s human population has increased and modern transportation has permitted, even promoted, settlement at considerable distances from city centers. Habitat loss comes hand in hand with development—loss with progress—but houses and roads are only part of the problem. Development creates new concerns, such as the suppression of wildfires in places where fires have shaped habitats. Look to the Florida scrub jay, for example. The habitat for the scrub jay is now less than 20 percent of what it was in the 1800s, thanks to fire suppression accompanying population growth and sprawl in the state. For this bird and many others, loss of habitat is the greatest threat, much of the time—but climatic change makes matters considerable worse in many cases. This is especially true for the Florida scrub jay, as sea-level rise leads to new losses of habit in the small percentage of their original range that remains.

While the Florida scrub jay’s range has contracted, other birds have expanded their population numbers with development and will continue to do so as climate changes. This seems like a positive effect, but often it is quite the reverse—one species’ expansion can lead to another’s contraction. Many a conservationist developed her early sensitivity to habit loss by watching one species crowd out another.

Birds have long provided models of moral rectitude and depravity alike. In the nineteenth century, introduction of European birds was promoted with enthusiasm, and then decried when the birds appeared to compete too successfully with native birds. Sometimes, the language used by naturalists and nature writers were indistinguishable from nativist writing about human immigrants from Ireland, southern Europe, and China. The English house sparrow was such a species, introduced to North America and then accused of displacing native birds and “fouling their own nests.” But there may be no better, and rather older, example of purported depravity than the behavior of the European female cuckoo, which lays her eggs in the nest of another bird, giving us the word “cuckold.” The Florida scrub jay (Aphelocoma coerulescens) appears to be at the other end of this moral spectrum. Unlike the cuckoo, the Florida scrub jay displays not just a family interest in raising her young but also shares responsibility for breeding with “helpers.” Apparently, it takes a village to raise scrub jays. Alas, morality and biology are seldom well matched; scrub jays eat the eggs of other species and are as omnivorous as any human gourmet.

In spite of habits of community breeding aid, habitat loss takes a toll, and populations of the Florida scrub jay were down to about ten thousand individuals in the 1990s, which include four thousand breeding pairs. State and federal listing of the scrub jay with other endangered species brings attention to the species, but what is needed is habitat—and connections between habitats. The habitat of the Florida scrub jay is a case study of fragmentation in the landscape. Once distributed throughout the middle part of the state, the range has been sliced and diced by development, leading to the current arrangement of small patches of habitat, scrubland with oak trees, which must have ground fires about once in twenty years to produce the food sources, such as acorns, that the scrub jays eat.

Far from seeing contraction in their range, northern mockingbirds (Mimus polyglottos) have been expanding their ranges, both breeding and year-round, for over one hundred years. As climate warms, they will doubtless continue to expand both of their ranges northward. As omnivores, mockingbirds do well in places that have access to environmental edges, where a greater species richness serves the bird’s needs and tastes. Although long a dominant resident of the once rural Southern states (northern mockingbirds are the state birds of five Southern states), northern mockingbirds make themselves at home in urban areas in the north—especially in open green areas such as backyards, parks, and cemeteries.

With their manifest intelligence and their ability to mimic other birdsongs, mockingbirds are often accepted as welcome additions to dooryards where they were once absent. I still thrill to the sight of one here in Maine, where they are summer visitors yet. But the success of the northern mockingbird comes as a cost to other birds, because mockingbirds outcompete other birds for resources of all kinds and may do so quite aggressively. Climatic changes are likely to exacerbate their spread northward without substantially cramping their southern habitat.

A phenological interest in birds can augment a broader interest in birding, or it can stand alone. For many, birding is a social activity. Organizations that promote birding provide opportunities for interested and knowledgeable people, or those hoping to join their ranks, to engage their interest in birds. There are, for instance, Big Day Counts, when groups of birders observe through a twenty-four-hour period, looking to create as large a list as possible of bird species observed through the eyes and ears. The American Birding Association sponsors Big Day Counts in the United States and has overtaken the National Audubon Society as the leading organization devoted to birds, as distinct from broader environmental concerns. The American Birding Association took over publication of North American Birds, an authoritative journal of birders’ reports, from the Audubon Society, which published the journal as American Birds. The best known Big Day Count occurs as the Christmas Bird Count, still organized by the National Audubon Society.

Since there is so much help to be had, it is perhaps a good idea to develop your knowledge of local birds in social circumstances, so that you can easily identify birds that make their way into your dooryard. Birding with knowledgeable people is for many the best way to learn one’s birds.

There are the aforementioned guidebooks to birds, and others, of course. These require patience, as one sociologist of science quite expertly discovered. Guides come in two distinct flavors—those with highly idealized, correctly colored images of birds (Peterson and Sibley are the best known) and others with photographs (the Audubon guides). Neither is better than the other, and which to choose is a matter of taste. To find an identification, you need to start by knowing approximately what you are looking for. The identifications are organized in Sibley, for instance, in a recognized taxonomic sequence that begins with birds found in wetlands and hikes on toward the songbirds. You may, in time, begin calling the latter “passerines.” The guides provide clear images and notes on field markings, along with range maps (with images and maps appearing on the same page in Sibley, and maps at the back of the book in Peterson).

In many places, there are local guides and checklists. These are sometimes of the quality but, by definition, not the completeness of the guides I just mentioned. They are especially useful, though, in that they simplify the learning and identification process, since birds that are unlikely to be found in a place are excluded.

And identifying birds is indeed a learning process, and a somewhat challenging one at that—but not too challenging. Birding, from one’s beginner efforts through more expert stages, probably stands as a perfect example of what the psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi calls “flow,” a condition in which skill is closely matched to challenge, providing a state of energy, concentration, and pleasure. And visually identifying birds is only half the interest. Accomplished birders know many species by sound, as well. Think of it: you know, crudely, the difference between a songbird’s melody and the coo of a dove, but with some study it’s possible to identify many dozens of species by their calls and songs. The Peterson guide series sells a CD of birdsongs, but the treasure trove of bird audio is at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and can be accessed over the Internet.

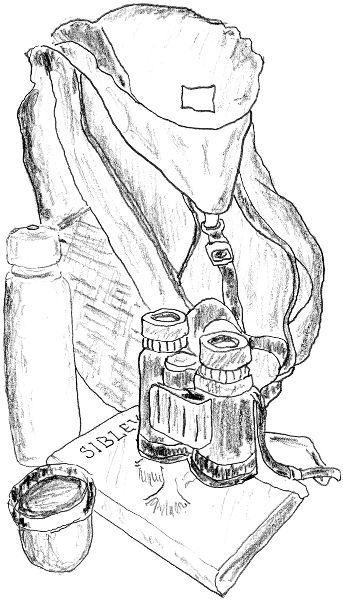

Figure 8.3. The gear for a morning to be spent watching birds: day pack, binoculars, a container with cup for coffee or tea, and a book for identifying birds.

There is gear, too, for those who like that sort of thing (a set in which I include myself). Most useful, and a badge of the birders’ art, are binoculars. A good pair have objective lenses that are not too large (the larger they are, the less stable your view unless you spring for stabilizing optics) and not too small (the light-gathering capability of larger-than-opera glass binoculars provides a clearer image. A pair of 7 × 35 or 8 × 50 binoculars is a good compromise. For certain kinds of birding, small telescopes are useful, and these are best mounted on tripods. Many birders like to photograph birds. For this, a digital single-lens reflex camera and telephoto or “long” lens are ideal, but discussion of which are well out of the scope of this book.

As you develop as an accomplished birder (assuming you aren’t one already and just reading to see what errors I might have made), you may wish to combine your knowledge of birds with other phenological interests, especially concerning sources of food for birds. Note, for instance, hatches of insects and the behaviors of birds when insects hatch. I marveled, one day, at the sight of a lone black phoebe (Sayornis nigricans) in my backyard, standing watch on a fencepost before lunging into the air only to snap to what seemed to be a complete halt, with the click of his or her wings. On investigation, I realized that the phoebe was tracking insects and audibly snatching them from midair.

Experienced birders watch for drunken bird behavior in the fall, when overripe berries ferment. Species of birds such as blackbirds and waxwings feast on the berries and are believed to suffer from the effects of alcohol in their systems. Climatic change may increase the number of bird species who “enjoy” this fall bacchanalia.

Long life lists and large counts appeal to some birders, and there is nothing wrong with that. Other birders prefer to focus on behavior, and for them, the breeding season offers great rewards. When watching birds, keep an eye out for these steps in the phenological cycle:

- Birds arriving in summer breeding habitat.

- Birds establishing territory.

- Birds mating.

- Birds nesting.

- Eggs hatching.

- Parent birds feeding hatchlings.

- Fledging.

In some cases, a full repeat of the process—mating through fledging. And then, departure to winter habitat.

Nesting, in particular, appeals to many, for several reasons. First, it provides a brief bit of mystery about where the nest is, if you begin by seeing birds carry nesting materials but haven’t yet found the site of the nest. Once that’s solved, you can watch the birds make the nest. There is nothing remotely parsimonious about the variation in the morphologies of birds’ nests. Every species has a different solution to the common problem of sheltering fertile eggs in such away that parent birds can brood and protecting hatchlings while they feed and grow. Indeed, that’s what is at issue: every nest has these two functions. Nests need to be cozy enough for the eggs and the chicks and, yet, sturdy enough to support the parenting birds. Given our human zest for constructing domiciles, there is a kind of instinctive mutualism between birds building nests and humans watching them. It goes without saying that you should do nothing to disturb the birds as they go about their business. This is the activity for which more powerful binoculars or telescopes, mounted on a tripod and at a good distance, are made for.

If it suits you, there is nothing to prevent you from knowing every nesting bird or bird pair on your phenological trail, from becoming familiar with their differing nesting styles, or from watching the full breeding process unfold, for several species of birds.

Something to be especially attentive to are numbers of eggs, numbers of hatches, and numbers of young birds at the end of the breeding cycle. The number of eggs is sometimes difficult to determine, although you could climb a tree a bit away from the nest to make a count—in some cases. Northern orioles build pouch-shaped nests that hide the eggs from view, as do cliff swallows. If you are lucky and devote enough time to observing, you may be able to pinpoint the exact time that the mother bird lays her eggs. Barring that, once you see one or the other of the parent birds brooding, the eggs are there.

Predatory behavior, and parent birds’ defenses against it, are events to watch for while the birds brood their eggs and raise their chicks. These have significance for monitoring climatic change from year to year. As ranges expand, contract, and migrate, patterns of predation may change, whether it comes from other bird species or from predators that are not birds. You will want to note each instance of predatory behavior, the kind of predator, and whether the predator is successful.

The greatest concern for ornithologists and birders alike are the innumerable opportunities for mismatches between breeding birds and their food supply, as when birds produce larger clutches in warmer seasons, but some of the insects (and other invertebrates) they depend on for food are actually decreasing in a warming climate.

More than any other form of wildlife, birds offer a glimpse at the spectacle of climatic change and its connectedness to the web of life. A phenological eye heightens an observer’s grasp—heightens your grasp—of the many connections in nature and the ways that these are altered as climates warm and change. Because of our species’ interest in and love for birds, there will be success stories like that of the California condor, successes in rescuing birds from near the point of extinction. But there will be losses, too. Every concerned birder, as Peterson fervently believed, increases the chances of success and decreases the risk of bird species vanishing from the face of the earth.