RECLAIMING SKILLS

Movement, Preparedness, Fire, and Shelter

The average modern human has no idea how to walk in the woods. Shoes turn most people’s feet into iron-clad tanks that crash and crush, so that they have no awareness of what is underfoot. The modern shoe is the house of the foot, creating a tight seal that separates our feeling and sensing feet from the textures and contours of the living earth. Perhaps it was reading about Hobbits that first inspired me to want to walk through the woods quietly and with awareness. According to Tolkien, Hobbits are known for this ability. As a kid, I used to practice jumping from rock to rock on the trails in the woods around my father’s house. I noticed early on that stepping lightly on stones made my footsteps almost completely silent, while stepping on dry leaves, twigs, and branches made lots of noise. As boys, we’d spend days upon days playing soldier or Kick the Can, and the need to sneak made learning to move quietly a valuable skill.

Of course, as I grew up and began to learn to meditate, I became more sensitive to the mood of the lands I was exploring and the way that my own movement and presence disturbed what Tom Brown Jr. calls “the baseline” of the forest, or the sounds and activity that occur when there is no disturbance or sense of threat among the creatures of the forest. The birds, squirrels, and other creatures are going about their day, when suddenly three hikers enter the forest, stepping on twigs, talking loudly, and setting off multiple “alarms” as every forest resident calls out a warning. In a few moments, the forest is silent, and everyone has fled or is staying out of sight until the intruders are gone. Each time we move on the land, we create what Tom Brown Jr. calls “concentric rings,” like those of a pebble tossed into a pond. It takes awareness and skill to move over land without creating big rings of disturbance. When we arrive in our nature location to meditate, it takes ten to fifteen minutes before our concentric rings die down and the forest baseline returns to normal.

While sitting quietly in the woods, I have often been startled to see a deer appear only yards away, as if the deer had been teleported to that location without making the slightest sound. Deer are masters at moving silently through the terrain and blending in with their environment. In fact, their primary defense is stealth. When deer walk, they place each hoof with precision.

For most of us, not knowing how to walk with awareness isn’t really our fault. We were never taught how to breathe properly or to move with awareness and skill through the woods.

Here is an awareness practice for walking in the woods, which I call “Don’t Step on a Twig!” The goal with this walking meditation is to avoid stepping on twigs and making loud sounds that startle the forest. In order not to do this, though, there are a few things you need to do.

The first is that you need to pay attention to how you are walking. Most of us walk heel to toe, which means that when we take a step, our heel lands first and then we roll onto the front of the foot. This way of walking came about when we started wearing shoes with heels for walking in cities and on cobblestone streets. On hard surfaces, there is less need to be gentle and skillful with our gait. When our ancestors walked barefoot, however, they walked toe to heel. They explored the terrain with the ball of the big toe, rolled their weight out to the pinky toe side of the foot, and then gradually lowered the heel. When you walk this way, you have much more awareness of the terrain and can avoid applying too much downward pressure on twigs and sticks, which will prevent you from making a lot of noise.

Try to walk this way barefoot at home before trying it in a park or in the woods and notice the difference: Lift your foot slowly, place the ball of the big toe first, feeling to make sure that the surface below doesn’t make a sound. Then roll to the outer edge of your foot, still sensing the surface below, and adjusting accordingly. Slowly and mindfully, lower your heel down. If you sense something under your heel, do not lower it all the way down. Instead, keep the weight on the front of your foot as you lift the other foot to continue walking. You’ll need to keep your knees slightly bent, and you may even place your hands on your thighs just above your knees for support. Tom Brown Jr. and Jon Young call this “the Fox Walk.”

You will also need to walk more slowly and mindfully than you normally do. If you do this while breathing consciously, the combination of breath awareness and slow, mindful steps will completely change your experience when you’re outdoors moving over land and through different ecosystems. You may also begin to relate more deeply to deer medicine and find yourself blending into the landscape.

It is important to pause regularly when walking in this way and to pay attention to what is moving all around you. Over time you will find that your senses get stronger.

As a child, I lived in a home that was made almost entirely of wood, with exposed beams, one of which was salvaged from an old farm house. It must have been at least 150 years old. In bed, I would stare up at beams made of cedar. There was always something comforting about those beams; their grain and texture provided something to ponder. As I tried to fall asleep, I might also stare down at the wood-plank floor. The knots and grain of each plank morphed into faces or scenes in my mind. The pattern of wood is one we have known forever, and there is much to see when meditating on its qualities.

Wood is our friend. Trees give us much of the air we breathe, shade us from the hot sun, feed us with their fruits and nuts, and extend branches we can climb to get higher and see farther than normal. They also give of their bodies so that we may eat and so that we may fashion tools and other objects that allow us to thrive on this good earth. Trees are alive, and their wood is a gift. When walking among them, be respectful. Never harm a tree unnecessarily, for they do feel and sense their world. When gathering wood for a fire or harvesting a live tree to fashion a tool, please use it wisely and with reverence.

Invite an ethic of reciprocity and gratitude into your rewilding. It affirms the reality that everything is connected and that when we take, we have a responsibility to give back, so that the equilibrium of living communities stays in balance. Often this is a personal and even private affair, a prayer of thankfulness upon finding wintergreen berries in the snow or offering a pine cone mandala in gratitude for a beautiful sunset. These gestures may at first feel childlike, even silly, but they open powerful doorways in our awareness and open our hearts to the universe.

Prayer is speaking to that which you consider to be divine, transcendent, holy. To pray in nature is to speak to and with the Great Mystery. In my own experience, praying outdoors allows the more-than-human world to interact with me in moments of vulnerable conversation with the mystery of life. Whatever your outlook or belief system, allowing yourself time and space to practice speaking from your heart, directly to the source of life, is restorative and positive.

Outside the enclosed walls of human-made spaces, the holy air moves and speaks; birds punctuate our thoughts with songs, calls, or alarms; birds of prey soar overhead, and clouds cover or reveal the life-giving light of our home star. When the spirits of the land move in times of heartfelt and reverent conversation with God, connections are nourished between us and all living things. We may find ourselves embraced physically, emotionally, and spiritually in a much larger family than we usually find ourselves in. Feelings of loneliness and isolation give way to wonder, awe, and profound gratitude for the gift of life and the beauty of this living earth.

At one time, a vast array of skills ensured our ancestors’ survival as they lived in intimate reciprocity with their environment. Knowing the plant beings and animals with whom we share our land, reading the weather, being able to birth fire, fashion shelter, and make the tools and other necessary items for living day to day are essential aspects of human rewilding. I have found great joy in learning and mastering these skills. Whether it is bringing forth fire in the palm of your hand, making nutritious tea from the abundant needles of coniferous trees in your region, or knowing how to create a shelter that will keep you alive in adverse conditions, these utilitarian skills are also spiritually nourishing. And they address our innate need for connection with the living earth.

Mindful awareness helps us to experience survival skills, as they are sometimes called, in an entirely different light. We’re not working from a frontier mentality that considers nature something savage and brutal we humans are meant to tame and conquer. We also don’t consider nature a two-dimensional warehouse of resources meant for our exploitation. Using these ancient skills can help us to come into right relationship with the earth and ourselves. They can open doorways of awareness that deepen our connection with the sacred web of life, in which we are nested, helping us to rediscover our place in the universe.

I discovered this to be true in my own journey of integrating mindfulness with ancestral skills. Most meditative traditions have deep roots in nature and remote wilderness. The forests, mountains, deserts, and jungles of the world have long called out to those seeking the answers to life’s deepest questions. Why then shouldn’t these worlds be bridged again by the basic skills of living in intimate relationship with nature, so that those who feel drawn to the great mysteries of life can also feel more confident, more empowered, and more self-sustained? Rewilding can connect us with the real world, our first world. Knowing that I can fashion a shelter if I need to, or make a fire and otherwise see to my basic survival needs gives me a sense of assuredness, relaxation, and calm.

Recently I was hiking up a mountain with my children, who are now six and eight. My littlest one, Cora, said to me, “Daddy, if the sun went down and we were stuck up on this mountain, you could scrape your knife on your fire stick and make fire for us and build a debris hut. We’d be okay, wouldn’t we, Daddy?”

“Yes, Cora, we’d be okay,” I said with a reassuring wink.

We’ve spent enough time outdoors, making fires, foraging, and building shelters that she feels safe far from the comforts of home, and as her dad, knowing that she is comfortable and confident warms my heart. For at the end of the day, what is my primary function in this life if not to help my children feel safe, self-assured, and positive in the world they inhabit? Feeling safe begins with feeling comfortable with the planet itself, with different environments, the weather, and other living creatures. This familiarity sets the stage for a sense of belonging and a positive outlook on life. With a strong bond to a place, knowledge of the local flora and fauna, and a core set of skills for attending to your basic needs outdoors, you will enjoy a fulfilling, lifelong relationship with a greater power.

I believe that everyone benefits from knowing how to attend to their own basic survival needs. The ability to find or create shelter, birth fire, treat water, fashion necessary tools, and forage or hunt for food will make anyone feel more secure away from modern industrial society. These abilities also place you in direct communication with the living earth, where the greatest gifts can be found. Having these skills will not only save your life if you are ever in the wild on your own, they also have the power to save your soul from a nature-deprived life. Learning to make a fire, becoming familiar with wild edibles in your area, being able to improvise a shelter, staying warm, and seeing the silver moon through the tree branches are all a kind of vital medicine. These skills give us access to a vital part of our inner nature and place us in direct contact with the earth and the universe in a grounded and embodied way.

Years ago, when I first learned the skill of making fire through the bow-drill method (which we will explore later in this chapter), I proposed leading a workshop on it at a retreat center. I told the retreat programmer that people need to know this skill. She seemed perplexed and said, “Micah, that is a very cool thing, but why does anyone need to know how to do this?” At the time, I was so surprised by her reaction that I was not sure how to respond. It seemed obvious to me that this was a vital skill. The experience of spinning the spindle into the hearthboard until aromatic cedar smoke begins to billow and a tiny glowing coal comes alive is one of the most profound things I had ever experienced. But the programmer did not know the power of that experience, and from a purely utilitarian perspective, she had a point — after all, we have lighters and matches now. Why would anyone need to know how to do this anymore?

So many things have been made easy for us. We don’t need to walk as much because we have cars, mass transit, electric skateboards, and Segways to move our bodies around the world. Our food is packaged, seasoned, and ready to eat. With the consolidation and mechanization of agriculture, there are fewer and fewer farms, and with the robot revolution currently under way, millions of manufacturing jobs will disappear over the next couple of decades. There are even automated electric lawn mowers for those who do not want to deal with maintaining one of the last vestiges of “nature” in the suburbs. What is there left for us to do? Many of the giant tech companies are talking about basic universal income for the masses, yet even if that happens, what are we to do with ourselves? Is this good for us? I can remember when the video game Rock Band was all the rage. I wondered if a whole generation of kids would grow up learning to play air guitar and never know the joy that comes from actually working hard over time to play a real guitar and actually rock.

A lot of kids grow up without learning to split wood or to whittle, to ride horses or motorbikes, to fish or to climb trees. Some people are going decades without allowing their bare feet to touch the ground. We have created technological worlds, and we are learning to navigate the internet and write code, pretending that this human-made world is apart from the support and grace of the natural world outside. I believe it is essential for our well-being as a species and for the well-being of the planet and the other species we share it with to stay connected to the old ways, to our hunting and gathering heritage.

Humanity today is like a waking dreamer, caught between the fantasies of sleep and the chaos of the real world. The mind seeks but cannot find the precise place and hour. We have created a Star Wars civilization, with Stone Age emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology. We thrash about. We are terribly confused by the mere fact of our existence, and a danger to ourselves and to the rest of life. E. O. WILSON1

I am not advocating a Luddite approach, where we have to throw our iPhones in the trash and live off the grid, although there is nothing wrong with choosing to go that way. I am suggesting that most people would benefit from regularly logging off the internet and logging on to the “wood-wide-web.” The average person has a need now and then for a crackling fire, wind in their hair, a refreshing swim, the weight and balance of a stout walking stick, and the feeling of being sheltered by the flesh and bones of the land. Our biology has not changed since we moved indoors. Our love for open spaces, water, high ground, and trees is baked into our physiology. Our need for refuge and for a place from which we can look out with a higher and wider perspective is an integral part of who we are. We still need to know that we are an integral part of this earth, that we belong, and that whatever continent our ancestors came from, we can endeavor to become “naturalized” to the land on which we now live.

In the pages ahead, we’re going to explore some basic skills for rewilding your life. This chapter is by no means a comprehensive guide. Think of it more as a starting point to get you on your way. The knowledge and skills of our ancestors, on every continent, are vast and deep. I like to remind myself to stay humble no matter what because there is always more to learn. These words from Isaac Newton offer good inspiration:

I do not know what I may appear to the world, but to myself I seem to have been only like a boy playing on the seashore, and diverting myself in now and then finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.2

Being Prepared

An essential discipline for being outdoors is to get into the habit of being prepared. This means checking the weather ahead of time, dressing appropriately, and bringing along any additional layers and gear you may need for a changing forecast. Here are some important guidelines to keep in mind.

1. Weather. Check the weather and plan accordingly. Having a good weather app on your phone is important. If you can install weather updates, this can be helpful, too, especially having a function that will alert you to lightning strikes in your area. This first tip about using your phone may seem to go against my earlier advice about putting away your phone when in the wild. In my work we have two rules about phones in the field. Rule Number One: Use your phone to check the weather to stay safe and to call 911 in an emergency. Rule Number Two: Stow the phone. We put away the phone so that we can enjoy nature through our senses. That said, because weather can be the determining factor that affects our safety outdoors, up-to-the-minute weather updates are invaluable.

2. Stay found. Always let someone know where you are going to be when heading into the field and also when you plan on getting back. I recommend getting to know a particular place near where you live, perhaps the same general area where you go for your nature meditation. Get to know this place well through all seasons. When you decide to explore a new, nearby territory, orient yourself to the topography of the place you know. Study maps of the terrain and notice other landmarks. Stay on the trail unless or until you are very familiar with a place. Get into the habit of finding your current location on a map so that, in the event of an emergency, you will be able to know where you are and chart a course home.

3. Clothing. “There is no such thing as bad weather, just bad clothing,” according to a Norwegian proverb. Dress appropriately for the season and the terrain. If there’s a possibility that you could get wet and that the temperature could drop, do not wear cotton clothing if possible. If you are exploring an area where you gain in elevation, know that weather can change quickly, especially in the summer. Wearing layers and having extra layers in a backpack is key to comfort in most outdoor settings. The tropics are an exception to carrying extra layers, but there, too, you want to have a breathable base layer. Elsewhere, your breathable base layer can be merino wool, which wicks moisture away from your body. Your mid-layers can be a fleece jacket or a wool sweater and a water-and-windproof outer layer, such as the Gore-Tex brand. The value of a good outer layer can’t be overstated. It is like having a wearable tent. To complete your outdoor attire, a pair of waterproof pants, a hat, gloves, and extra socks (in case the ones you’re wearing get wet) are also essential. The goal is to stay dry. Hypothermia is the number one killer outdoors, so staying dry and warm is always your goal. With appropriate clothing you can be outside for days and maintain your core body temperature.

In the outdoor trainings I lead, we are outside in the shoulder seasons for nine-day intensives. Weather in western Massachusetts can vary wildly in the spring, early summer, and fall. We are out for twelve hours a day, in cold, driving rain, snow, mud, and temperatures ranging from the mid-20s to the upper 70s. When everyone comes prepared, we can be outside without worry for over a week and have a great time, so we emphasize the importance of proper clothing. It’s about safety first and foremost, but it’s also about feeling at home outdoors and staying in that home longer.

What to Bring?

Depending on your plans for the day, there are a lot of possible gear combinations you might like to bring with you to be prepared. Here are two levels of preparedness to guide your plan.

The Park Bag

If you are heading into a small park or other outdoor area where you won’t ever be more than a few hundred yards or so from the human world, you don’t really need to bring too much with you. Here are a few essentials: cell phone, a small first aid kit, water, snacks, emergency whistle, field guide, map, extra layer, hat. I recommend having a small hip or backpack preloaded and ready to go, so that when the mood strikes, you can grab and go.

The Field Bag

If you plan on being out for the day, you should plan on bringing enough with you to stay out for the night just in case you need to. Here are the essential items you should have in your field bag:

1. A cell phone with a solar charger. Make sure your phone is fully charged when you set out but also take a charger. You can purchase a solar charger for around twenty dollars. Not only does it allow you to recharge with sunlight, it also serves as an energy bank and usually has an integrated LED flashlight as well. You want your cell phone in case of an emergency and so that you can check the weather periodically.

2. A first aid kit. It should include bandages, including an elastic bandage, gauze, cloth tape, a tourniquet, a small roll of duct tape, pain and anti-inflammatory medication, allergy medication, and tick-removing tweezers in addition to your personal preferences. Download the Red Cross First Aid App on your phone. If you are a few miles or more from help, any injury can become more serious, so be prepared to stabilize and treat an injury quickly.

3. Water. For a daylong excursion, take two liters of water with you. Also pack a few iodine tablets for treating water should you be out longer than expected and need to treat water for drinking. The LifeStraw brand offers a convenient alternative to iodine tablets. If you know that you’re going to want a hot cup of coffee or tea or another warm drink while you’re out, bring a packable pot for boiling water, which is another way to treat water.

4. Extra food. Always bring more food than you think you will need. Nuts, dried fruit, jerky, and protein bars are great options. The food we eat acts like a fire in our bodies that generates heat and energy. When out in the field, especially if you end up being out longer than you expected, or even overnight, you’ll need fuel to throw on the fire to help it burn all night long. Avoid high sugar foods, which are only good for a short burst of energy. A balance of complex carbohydrates and protein is ideal for sustaining energy.

5. Emergency whistle. Many backpacks today have whistles integrated into their sternum straps, which is brilliant. If you are ever lost or in trouble, an emergency whistle allows you to sound an alarm. It is much more energy efficient and effective than yelling. These whistles are inexpensive and available at outdoor equipment stores, online, and even at some gas-station convenience stores. Make sure you carry at least one in your field bag at all times.

6. Field guide(s). I traveled for years with a copy of my Peterson Field Guide to North American Trees always in my bag. That book is full of pressed leaves I picked up on my walks. It even holds the tail of a chipmunk I found under the perch of a red-tailed hawk! Depending on your interests — whether trees, birds, animal tracks, clouds, mushrooms, insects, etc. — bring a field guide or two or download their apps on your phone to keep your bag light. A guide is a great resource for observing nature. I still prefer opening a book to pulling out my phone, since I don’t want to get pulled into distractions on my phone.

7. A journal and a pen. You’ll want a durable journal and a pen for sketching, making notes, or simply writing down the experience you have while communing with the living earth. Spending reflective time outdoors can catalyze insights, ideas, memories, and other experiences that you feel compelled to document.

8. A map and a compass. A topographical map of the land you are on along with a baseplate compass for charting your route are useful for basic orientation. Of course, most phones now have a built-in compass, but having a physical compass and being able to use it with a physical map allows you to leave the phone safely stowed away. And they work when the phone runs out of power.

9. A multi-tool. I am a big fan of the multi-tool, which is similar to a Swiss Army knife. Most multi-tools today have pliers as the central function, with different blades, screwdrivers, bottle and can openers, files, wire cutters, and other tools. If you can, buy a high-quality multi-tool. There are a lot of cheap knockoffs, which I haven’t found to be of much use in the field. You can use a multi-tool for foraging, shelter-building, fire making, cooking, and other tasks on a hike or around camp.

10. A fire kit. Every field bag should have a tool for making fire. Depending on your preference and skill level, it could include waterproof matches, a lighter, a ferrocerium rod and striker, flint, a steel and char cloth, a hand or bow drill kit, and tinder. (We will discuss the various ways to kindle fire later in this chapter.)

11. A headlamp. A good headlamp is essentially a flashlight attached to a headband. Flashlights are useful, but they are difficult to use when performing camp tasks or hiking at dusk when you want your hands free to maintain your balance on a trail. A headlamp allows you to put light where you need it while freeing both hands. You can also use a headlamp to signal to other people if you ever get lost. Most come with an automatic flashing or SOS function.

12. Extra clothes. Additional layers, socks, gloves, and a hat are essential in your field bag. If you take a wrong step into a stream and get your feet and body wet, changing into dry clothes will keep you warm and protect you from hypothermia. In a pinch, you can also use extra socks as gloves.

13. An emergency blanket. Pack a reflective emergency blanket that will help you conserve body heat if you are out longer than expected. They are inexpensive, light, and easy to pack. They can also be used as a reflecting surface in an improvised shelter to help reflect the heat from your fire into your sleeping space.

14. A tarp or a rain fly with cordage. A compact tarp or a packable rain fly is the final essential piece of equipment in your field bag. You can use it to fashion shelter quickly so that you stay dry and out of the wind. You can tie up a lean-to shelter between small trees, or use a hiking pole as a center pole, staking the corners to the ground. In any case, you’ll never regret having this item at the bottom of your bag when the need arises.

There are certainly many other items you could include in your field bag, like a small hatchet, a folding handsaw or pruning shears for making tools, a long-burning candle, a small hammock — but in my experience, these basic fourteen items are the most essential. As you spend more time outdoors, you’ll customize your own essential list.

MEDITATION FOR ENTERING THE WILD

It’s important to transition into a place of present-moment awareness before entering the more-than-human world. You don’t want to plow through like a runaway train. Prepare to mentally downshift from the outcome-oriented and hyper-focused mental state we are often in. Shift to a slower, more receptive space to attune to the rhythms of the land and the creatures whose neighborhood you now will be entering.

Before embarking on a journey into a forest, meadow, or other wild space, take a few moments to center yourself. Pause. Close your eyes. Take a few slow, deep breaths. Let the exhalation be twice as long as the inhalation. Let go of whatever thoughts are rattling around in your head, whatever stress or worry you are transmitting. Empty your cup. Tune in to the sounds, sensations, and rhythms of the land all around you. Stretch out with your feelings and sense the life presence of the living earth. Know that the beings who call this land home are paying close attention to what is going on. They have to — their lives depend on it. Your presence will be felt, noticed, and communicated far and wide. Notice the birds and the chipmunks; notice the little creatures we sometimes think of as background noise. In a relaxed way, be curious, and with your eyes closed, notice everything that is happening around you. Take a few minutes to be with it all.

Then open your eyes and look around. Take some time to simply observe everything. Now take a moment to express your gratitude to the land. You may even ask permission of the earth for your time in this space, sending reverence to all the inhabitants. Enter the land with respect. Set a strong intention to stay present and connected with your breath and to create as little disturbance as possible. Let each footstep be an experience of soulful connection with the living earth, each breath a rite of interbeing with the holy winds that blow, with all life that shares the breath.

With time, this practice for entry will transform how you approach your time outdoors. You want to bring awareness to your rewilding, to be mindful of your surroundings and how you show up. In time you will grow into comfort and belonging on the land.

Fire, Our Friend in the Wild

Before television and touch screens, there was fire, our friend and comforter for millennia. In Sanskrit, the word for fire is agni, and it is the very first word written in the Vedas, the oldest sacred books in world literature. As I noted earlier, Hindus give the first word in their sacred texts special importance. To reflect on the word agni is to find the seed that contains all the wisdom of the Vedas.

Fire is central to human culture. Mastering the art of creating fire was a turning point in our evolution as a species, and this is reflected in the myths and legends of peoples all over the world. Fire gives both light and warmth. Fire allows us to cook our food and heat our shelters. By its very nature, it calls us into circle practice, as we instinctually gather around. Fire’s mesmerizing display of color and light guides our awareness into a state of soft fascination, relieving fatigue and bringing us into a state of trance-like meditation. It also creates a perfect setting for bringing the day to a peaceful and collective conclusion. Fire guides us into a natural state of harmony and healing, individually and collectively.

Yet many people today live in places where making a natural fire may not be an option. Here are some simple options for bringing the element of fire into your life.

• Candles. Especially in the darker and colder months of the year, lighting candles can be a wonderful way to bring fire into your home. At the end of the day, consider turning off all of your electronic devices, lower the lights, and light a candle or two. Allow your senses to rest in the natural darkness. Gaze into the flickering flame of a candle and allow yourself to enjoy the simple beauty of its flame and the light. A candle is a miniature campfire. Candle meditation can help you drop into the present moment in a deep and meaningful way. A candle can also serve as a centerpiece for a family council or meeting, where everyone shares while enjoying the candlelight.

• Incense and other sacred herbs. Burning incense, aromatic herbs, or tree resins like frankincense and myrrh is another way to invite the fire element into your home and life. The burning ember releases both smoke and aroma, which can be stimulating to the mind and the spirit while soothing through your sense of smell. Sitting and gazing at the dancing smoke can also be a sweet meditation.

• Fireplaces and woodstoves. If you already have an indoor place for fires, then you can add meditation practices to your enjoyment of their warmth and light.

• A screen fire. In a pinch, another option is television fire, or “slow TV” as they call it in the Netherlands. Netflix, Amazon Prime, and YouTube all offer fire channels that make your television or handheld device a miniature fireplace. Although purists may scoff, I have found this to be a wonderful option when an actual fire just wasn’t viable.

Watching curls of smoke from incense or candles writhe and dance, especially on a cold, rainy afternoon, can draw us into the present. It’s just a moment of peace, but it’s also something more, something that arises from a certain kind of smoke. The smoke lifting off an incense stick and the smoke rising off a crackling fire of dry pine are a phenomenon of unique power and character. Smoke is so often dismissed as less than fire or just a byproduct. Yet smoke itself has a story. Smoke reveals the movement of the invisible air. Life-giving winds are given shape by smoke, like the invisible man who is suddenly revealed when covered with paint.

In the Lakota tradition, smoke is believed to carry the people’s prayers skyward to the Great Spirit. Watching smoke dance is perhaps one of the most ancient forms of meditation. In monasteries and ashrams all over the world, incense is burned to clear negative energy, sanctify holy spaces, and brighten the mind for meditation. Smoke meditation can help us connect with the elements of air, space, and fire.

GUIDED SMOKE MEDITATION

Light your favorite incense or make a small fire outdoors. Then sit comfortably and slowly allow your breathing to deepen. Let attention rest on the dancing flame or smoldering red embers. Keep breathing consciously until the mind begins to settle. Bring your attention now to where the smoke lifts off the flame or ember. Gaze at the ever-changing movement of the smoke. Allow yourself to simply enjoy and be carried by the rising, curling, dancing smoke. Whatever worries, fears, concerns, or burdens you may be carrying, offer them up. Whatever you may be feeling thankful for, let it rise. If you have other prayers or deep desires in your heart, imagine them lifting off and being carried away on the wind. See your gratitude rising into the sky and being received by the cosmos, extending infinitely above you.

Fire 101

As a child, I watched a movie called Quest for Fire, about a small group of Neanderthals who encounter a community of early Homo sapiens for the first time. Unlike the Neanderthals, the humans had learned the art of creating fire, and the Neanderthals watch transfixed as a woman demonstrated the skill. She twirls a stick between her palms with its tip touching another piece of wood, first slowly and then faster and faster, until a thin wisp of smoke begins to emerge from the dust the friction creates. She bends down and gently blows on the small mound and then gently transfers it into a bundle of tinder. She keeps breathing into the tiny nest in her hands until the smoke begins to billow and suddenly a flame jumps out of her hands. Fire is born!

The look of total wonder on the Neanderthals’ faces is the same look that students of the outdoors get when they see fire brought forth in this way today. It is the look I had on my face the first few times I witnessed this ancient human ritual. And it is a ritual. It must be done in a certain way, under certain conditions, and with a certain attitude. If everything is done in the right way, a transformation of heat, fuel, and oxygen happens — and it gets me every time. Some people who have seen me demonstrate this technique have wept. In our modern age especially, when few people carry lighters or matches anymore, to see fire brought into being the old way triggers a deep response. This skill connects us to our earliest ancestors. Every single human being has ancestors who knew and used this technique.

Learning how to make fire requires skill and responsibility. Fire can cause terrible destruction. Being a firekeeper, someone who creates, sustains, and works with fire respectfully and reverently, means making safety your number one priority. Know your local zoning rules and laws regarding fires. Pay attention to local fire warnings or bans. Never make fire in dry windy conditions, and always have enough water on hand to completely douse any fire you make. Avoid making fires in places that do not have an existing fire scar. Be responsible, courteous, and aware when collecting fuel from the land, and always leave the land in better condition than you found it.

Fire requires three things: heat, fuel, and air. Heat comes from a match, lighter, spark, or friction. Fuel is tinder and kindling and larger pieces of wood. Tinder is tiny, dry material; twigs the width of pencil lead, the cambium (inner bark) from dead trees, and white-birch bark are all great tinder. Newspaper and dryer lint are also commonly used as tinder. Kindling is slightly larger material, usually twigs and sticks that are a little bigger than tinder. As you collect your material, stack the tinder and kindling in separate piles, so that you can feed your fire slowly. As the heat grows, you gradually add larger fuel. Once you have a good fire going with the kindling, you can add larger pieces of wood. You’re not building a bonfire (which is not necessary and actually an inefficient waste of fuel).

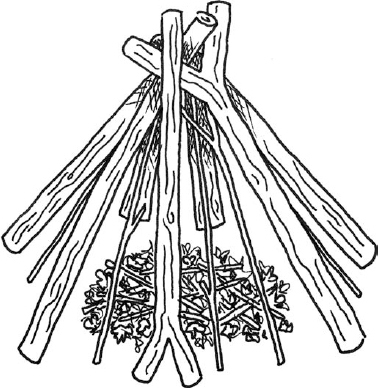

The Tipi Fire

The most common and effective type of fire to build is called “a tipi fire,” because it is shaped like a circular cone with the tinder at the base and kindling leaning against it in a circle, creating a tipi shape. Because heat rises, the incline of the tipi fire allows the fire to climb up the fuel to the peak, creating a natural and effective convection current. And in case of rain, the shape of a tipi fire allows fuel to shed falling water more effectively than other types of fires, such as the log-cabin style, in which the pieces of wood are arranged in a flattish, broad square. If you are new to making fires, I suggest you start your first one with matches. See if you can build your tinder and kindling in such a way that you can use only one match to get it going.

To make a fire with matches or a lighter, pile tinder at the base of your tipi and light it. Have your dry piles of gradually larger kindling prepared before you light your fire, so that as it grows, you can feed it slowly and steadily. And have the larger wood nearby to keep the fire going.

If you are making fire using a more traditional method, such as flint and steel or the bow drill, you will need to create a small tinder nest to hold your char cloth or to receive a spark. It is called “a nest” because the tinder material is rolled into a small ball and then kneaded, massaged, and shaped into a small circular nest with a depression in the exact center where the char cloth or coal is placed in order to protect and nurture it until the tinder ignites in a flame. A tinder nest can vary greatly in size, depending on the materials that are available. You will want to become familiar with tinder sources in your area. Good tinder is composed of fine, dry plant fibers, although you can also use lint from a dryer, as mentioned earlier, which is highly flammable. (That’s why you should clean out your lint catcher as well as your dryer exhaust and duct, and never leave the house with the dryer running.)

Tipi fire

My favorite source of tinder is white-birch bark, which is highly flammable even when wet. The stringy inner bark of tulip trees is also excellent if it can be harvested from dead trees that have had a chance to start to dry out. The cambium of many trees can be peeled off and rubbed between the hands to loosen the fibers. But only peel bark off dead trees so that you do not injure living ones. The material can then be shaped into a nest. Simply press your thumb into the center of the compact bundle to create a central space for your flame or coal. If you are using dryer lint, you can place it in the middle of your nest or roll the lint itself into a nest. One of my favorite tricks is to wrap a thick strip of white-birch bark around my tinder nest in the same way you might see bacon wrapped around the outer edge of a filet. Once you light the nest, the ring of bark around the edge feeds off the tinder nest and provides good heat for the larger twigs you add.

A fire is like a baby: at first it needs small portions of easily digestible food, and then gradually it needs more food as it grows. The tinder nest provides the digestible fuel for your baby fire; it nurtures the ember that you will breathe into life and that ignites into flame. The tipi fire is a reliable and comforting fire, which you can master with just a little practice. Now let’s explore some other fires that require a good deal more practice but that are worth the effort.

The Ferro (Ferrocerium) Rod

Ferrocerium is a metal alloy that is scraped to spark a fire without matches or a lighter. Ferro rods, as they are called, contain magnesium and a metal, such as iron or steel, and sometimes the rare earth metal cerium. When scraped with a knife blade or a piece of steel, the rod throws off sparks that can burn as hot as 3,000 degrees — hotter than the temperature of molten lava! Ferro rods can spark even when wet, and because of their sparks’ high temperature, ferro rods are helpful for starting a fire in the rain.

If you decide to stock a ferro rod in your field bag, you might also take along a sealable plastic bag of dryer lint, which makes good tinder as it can easily catch a ferro spark and ignite. But a ferro rod can also ignite finely shredded white-birch bark, the dried cambium found underneath the bark of certain dead trees, as well as paper, cotton, shavings from resinous heartwood, and other tinder.

Arrange your tinder bundle, dryer lint, or other tinder on the ground, so that the sparks from the rod will fall into the nest. To throw sparks off a ferro rod, use the back of a knife blade. Please note that the back side of your blade must have a sharp right angle; otherwise, use a scraper designed specifically for a ferro rod. Once the spark ignites the tinder, add small twigs around the tinder in the tipi shape. As the twigs ignite, continue adding larger and larger pieces of wood until the fire is the size you want.

Flint and Steel

The ferro-rod method is different from the flint-and-steel method. Flint and steel do not involve the use of a ferro rod and are somewhat more challenging. The spark from flint and steel is close to 800 degrees, about 2,000 degrees cooler than a spark from ferro. In the flint-and-steel method, a high carbon-steel striker, which is shaped to wrap around the fingers (almost like brass knuckles) is struck against a piece of very hard stone, often flint of some kind. The hardness of the flint causes a very small shaving of steel to ignite and fly off into the air (the spark). Because this small spark is so much cooler than that created by a ferro rod, a material different from dryer lint is needed for tinder. We have to use something called “char cloth” to catch our spark.

Char cloth is made from cotton or linen that has been cut into small squares and cooked at a high temperature inside of a small tin (like the tin for breath mints) over a bed of hot coals for five to seven minutes. You can use an old tee shirt or a towel or jeans, but make sure that the fabric is all vegetable-based, with no synthetic material. Poke a small hole in the top of the tin with a hammer and nail or a knife, so that the smoke can escape as the cloth cooks and the tin doesn’t explode as heat and pressure build up inside it. After five to seven minutes, when smoke is still coming out, take the tin out of the coals using tongs. Set it on a rock or somewhere safe where it won’t ignite anything around it, and let it cool completely, until no more smoke is coming out, before you try to open it to retrieve the cloth. The cloth inside should be completely blackened or charred. If it’s not all black, you might want to repeat the cooking for another five minutes. The char cloth might be somewhat fragile to the touch after cooking, although you don’t want it to disintegrate. You need to handle it carefully and separate all the different pieces. You want to use only one at a time, but each char cloth will be ready to catch a spark.

Clear the space where you want to make your fire. Assemble the kindling and larger wood and arrange the kindling in a rough tipi that you can slip the tinder nest into once you have a flame going in the char cloth. Ready your tinder nest.

When you’re ready to make the fire, place the char cloth on your tinder nest and strike your flint with your striker until a spark lands on the char cloth and begins to glow and smolder. This may take a little while as it is hard to control where a spark will fly. You may throw off a lot of sparks that go everywhere except onto your char cloth before one lands and catches. Also, pay attention to where the sparks fly in case you need to stomp any out. Once a spark lands on your cloth and catches, you have a little time and can relax. A piece of char can smolder for at least a few minutes before it burns up.

Once the cloth is smoldering, pick up the tinder nest, put it in the palm of your hand, and gently press the smoldering char cloth into the depression in the center of the nest. Wrap the nest around the smoldering char and gently breathe onto the nest until you begin to see smoke. Keep blowing until that smoke becomes steady and abundant, and then blow harder until that nest ignites into flame. Place your flame on the kindling and keep your fire by feeding it with small sticks. Congratulations! You just birthed fire using an ancient method.

Take a few deep breaths and invite gratitude for the gift of this fire. Take a few minutes to sit with your fire, gazing into the flames. Simply be with your fire and notice its effects on you. Fire can be a powerful doorway to meditation. When you are finished sitting, extinguish the fire with water, making certain all embers are completely out.

FIRE MEDITATION

For our fire meditation, we build a very small fire that is intended to burn for only ten to fifteen minutes. The practice involves preparing, kindling, tending, and gazing into a small fire, and then allowing it to burn out completely on its own. We approach the creation, enjoyment, and passing of this living flame with reverence and respect. Most of the time during the fire meditation is spent gazing into the fire and allowing it to hold your focus. You may wish to speak to the fire, or you may want to place a prayer stick or a letting-go offering into the fire. You can imagine that the smoke is carrying your worries, prayers, or intentions. Here are the steps.

1. Set an intention. Before setting out to gather your tinder, kindling, and fuel, take a few deep breaths, close your eyes, and clear your mind. Turn off your phone and clear the next thirty minutes as sacred time with the element of fire. If you have a specific intention for your meditation, such as healing, forgiveness, letting go, or grieving, take a few moments to get clear about your goal.

2. Take a walk to gather tinder, kindling, and fuel. Pay attention as you go, and be aware of your surroundings. Move slowly and enjoy this simple task. You are outside, there is nowhere else you need to be and nothing else you need to be doing. Gather your fuel with reverence and gratitude. Gather only fallen wood or harvest limbs that are dead so you do not harm a tree. Just a handful of small twigs, eight to sixteen should suffice.

3. Prepare your tinder bundle and separate your fuel into little piles. Engage in this practice as you would a Japanese tea ceremony. Let the simple task of sorting absorb your attention.

4. Take a few moments to connect with gratitude. Ask for the gift of fire. Feel your connection to the long line of firekeepers who came before you. To be a firekeeper is to carry the hope of humankind. Kindle your tinder bundle with a bow drill, hand drill, flint and steel, or ferro rod. Give thanks.

5. Begin fire gazing. Take this time now to be present with the living, breathing fire. Feed it and allow your awareness to be absorbed in its light and movement. Allow the fire to teach you. Be open to what comes.

6. Allow the fire to die. Do not interfere with the natural way in which the fire burns through its fuel. Allow this natural process to unfold. Stay with your fire after the flame has gone out. Feel the heat still radiating from the coals. Be with the fire until no more smoke rises. In your own way, say thank you to the fire, and then gently and respectfully pour water or lay snow onto the cooling embers.

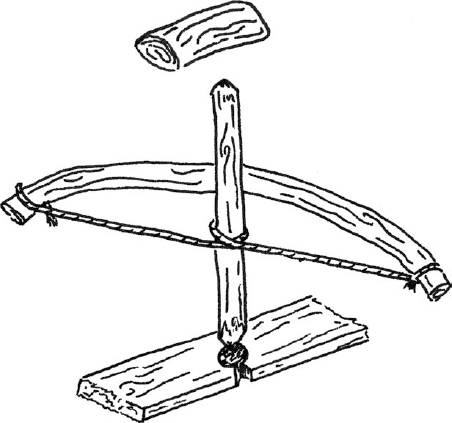

The bow drill is a technique for making fire with friction. You may have seen drawings of the tools in scouting manuals or basic survival books, although the details of exactly how to fashion a proper kit are often missing. Even if you have all the proper pieces and know how to use them, making a fire using this technique can still be challenging. In fact, I find that friction-fire practice is profoundly humbling. When I am gifted with a coal — a tiny, burning ember of wood dust that I then breathe into a leaping flame — the experience is made sweeter by the sweat equity and the sacrifice involved. A sacred fire, brought into being through the friction method, is not the same kind of fire as one brought forth with a lighter or match. It has a greater presence, meaning, and value to you, who brought it forth with humility and gratitude.

Bow drill

The bow drill has four components: a fire bow, hearthboard, spindle, and handhold.

• The fire bow is a bent piece of wood with cordage attached to each end. The length of the bow should be approximately from your armpit to your wrist. The cordage is wrapped around the spindle and used to turn it round and round, back and forth. This action creates intense friction between the spindle and the hearthboard.

• The hearthboard is a rectangular piece of wood with a pie-shaped wedge carved into the face of it. The spindle will grind down into this depression and create wood dust. The pie-shaped wedge collects and holds the wood dust, which eventually ignites into a coal.

• The spindle is a wooden rod about as wide as your thumb and as long as the space from the tip of your thumb to your pinkie finger when making the “hang-loose” sign. The spindle is turned by the back-and-forth motion of the bow, and it is the heat generated by the friction between the tip of the spindle and the hearthboard that creates the coal.

• The handhold is a stone or a piece of bone or wood that you use to press down on the spindle while turning it with the bow. The handhold keeps the spindle in place and protects your hand from the heat being generated. The point of contact between the top of the spindle and the handhold should be lubricated with sweat, ear wax, crushed pine needles, or other body oils to prevent excessive friction. You do not want to make a coal at the top of the spindle.

The bow- and hand-drill techniques are effective for making fire, of course, but they are also disciplines that have much to teach us about life. The spindle could be understood to represent male energy, the hearthboard female energy, and the coal the life that is created through the friction of male and female. To bring a coal to life requires passion, focus, skill, and stamina. Once a coal is born, you need to carefully and tenderly deposit the ember into a safe, supported nest of tinder. Then you blow ever so gently on that little coal, holding it in the nourishment of the fuel that it needs to grow into a dancing, living flame. This is the wonder of making a fire through friction. The lessons, healing, and meaning will differ for each person, but everyone I have ever seen make fire in this way — or even watch it being made — has been deeply moved.

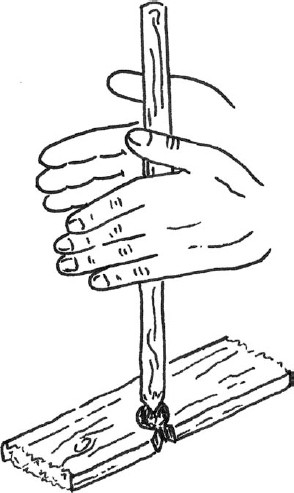

The Hand Drill

The hand drill is another ancient tool for starting a fire through friction. It has two simple parts: a hearthboard, which is a flat, thin piece of wood, and a spindle, which is a narrow stick about 18 to 24 inches long. Like the hearthboard for the bow drill, the hand-drill hearthboard has a place where the tip of the spindle rests and a pie-shaped wedge cut out where the wood dust that is churned out by the spinning of the spindle gathers and eventually ignites into a small, delicate coal or ember. The spindle is a narrow stick about 18 to 24 inches long, which is turned in place by rubbing it rapidly between the palms of your hands until the wood dust smokes and then ignites.

The hand drill has a certain elegance in its simplicity, but it is more difficult to master than the bow drill. The tool itself is light and easy to transport. Also, if you are ever in a survival situation, you can make a hand drill more easily than a bow drill. Yet because the hand drill is challenging, many people never try it, or they tend to give up after a few failed attempts. I myself often thought that the technique was beyond my ability, even after I had made a few coals with a bow drill. Something about the hand drill just seems unattainable, but I choose to keep at it.

To practice the art of fire-starting, especially with a hand drill, is to become a student to something old and sturdy. The latest iPhone or other technological gadget is only relevant for a few years and then becomes outdated or irrelevant — but the hand drill abides. What other technology is as old or as useful? In the end, fire is essential. A fire is a friend to keep you company and give comfort in the dark of night. It keeps us warm in the depths of winter and cooks the food that fills our bellies. Fire has long been the focal point of community gatherings and the center of council circles. Around the fire is where our stories have been told, tales of the day’s hunt and the great imaginings of how things came to be.

Hand drill

Our fire now is in our technology, which provides what we need to survive day to day but doesn’t give us all that we truly need. The crackle of a good small fire and the voice of the wind in the trees is a medicine that only the earth can provide. Tom Brown Jr. always teaches that before we endeavor to bring forth fire in the sacred way, we start in a place of gratitude. So here is a meditation to center you for this creative act.

GRATITUDE MEDITATION FOR BIRTHING FIRE

This life is a gift. Take a deep breath, and as you exhale, clear your mind. Let go of your agendas, plans, stories, opinions, and all the other stuff flying around in your mind. Take another deep breath and let it go. You are endeavoring to bring forth fire in the ancient and sacred way. Fire is a gift from the gods, from the spirits of the land. This way has been passed down for a long time. By practicing this ancient art, you are connecting to one of the deepest legacies in human ancestry. Allow yourself to be in this moment. You are in this eternal present moment that all people have been in. This is the same moment in which your ancestors brought forth fire. There is nowhere else to be and nothing else to do. Allow yourself to be here in this moment.

What do you hear? What can you feel?

Take a moment and give thanks for the gift of this breath. You are alive. Give thanks for your life. Take a few moments and give thanks for whatever comes to mind. If you can, speak words of thanksgiving aloud. If you have a deity or a language for speaking with what you consider to be divine, take this time to pray in your own way.

Let go of your intention to bring forth fire. Let go of any outcomes. Endeavor to undertake this simple and profound practice with humility and patience.

I tend to get pretty excited and pumped up about these skills. But sometimes I get so focused on the outcome of the skill that I lose track of the process. It’s like that with so many things in life, isn’t it? We focus on the money we are trying to make to buy the thing we want in the future, and in so doing, we miss the gift of the present moment, which is the only thing we ever actually have. Working with bow and hand drill is one of my favorite practices, but sometimes when I get to working on making a coal, I strive and strive for something like fifteen minutes, until I realize I haven’t been in a state of gratitude. And if I’m not in a state of gratitude, I haven’t been conscious of my breathing; instead, I’ve been contracted and tense, trying to force the process.

Recently I was in the woods sitting under one of my favorite trees working on a hand drill. I wasn’t getting even a wisp of smoke. When I finally realized that I wasn’t in a space of gratitude, I stopped what I was doing and centered myself. I started over again, and this time I stayed with my breathing, slowed down, and stayed very present with what I was doing. I began saying thank you out loud. Before long, I was thanking everyone who came to mind — old friends, my parents, my children, my wife, my siblings, the earth and the trees, the sun and the stars, my holy spirit. I found myself shifting to a treasured, old, sacred chant. The hand drill became a meditation. My mind was melting into my hands, into the spindle and hearthboard, and my mind was becoming purified by the intense focus. Smoke began to rise from the wood dust gathering around the base of the spindle. I kept working but eventually became tired and had to stop. I looked at my watch; thirty minutes had passed. I was covered in sweat.

I had not made a coal, but I didn’t care. I felt good. I had lost track of time and my mind. I had found the now. I realized something that day. Or maybe I should say that I re-realized something, something I had forgotten. With these skills, it’s not always about making fire but about getting to the place within yourself where you become the fire. It’s the work of becoming empty, of honing your physical skills and your mental skills to the point where you cease to be a creature made up of different working pieces and instead become a unified consciousness, capable of bringing forth life and untold creative wonders. Like the fire born out of a churning of spindle on a hearthboard, the light of our own burnished awareness is the true gift of these skills. This means that the practicality of the hand drill is but one of the layers of this technique. It feeds the body, mind, and soul.

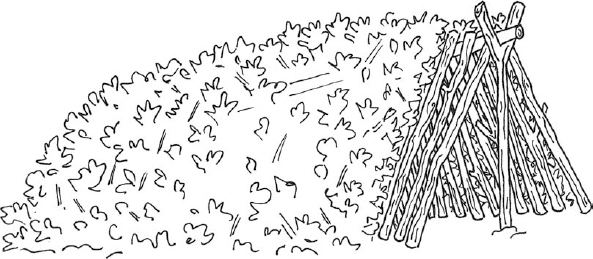

Shelter

Improvising a shelter that can keep you warm and dry enough to survive outdoors on a cold night is a valuable skill. If they found themselves in such a situation, few people today would know where to begin. Knowing how to make your own shelter for sleeping outdoors will improve your experience in the wild. Our modern houses create such a comfortable indoor environment that it is easy for people not to go outside at all. But indoor environments dysregulate our circadian rhythms, cutting us off from natural sunlight during the day and bombarding us with artificial light at night. (It’s a good idea to try to phase out screen use after eight o’clock at night so that you can allow your body to begin winding down more naturally.) Camping for a few nights has been shown to be an effective intervention for resetting circadian rhythms and improving sleep.

Here are a couple of shelters everyone should know how to make because they require few tools or other man-made objects.

Anyone can construct this simple design, which acts as both a shelter and a sleeping bag in one. I learned this technique at the Tom Brown Jr. Tracker School, in the Pine Barrens of New Jersey. It was inspired by the nests that squirrels make out of sticks and leaves. One of the great things about the debris hut is that you are essentially sleeping inside of a big pile of leaves. This, in itself, is incredibly stimulating for the senses.

Here’s how it works. You will need one long ridge pole and many shorter sticks of varied lengths. The ridge pole should be a branch or a small fallen tree trunk or sapling, about a foot longer than you are tall. One end of this pole will rest on the ground, and the other will lean against a tree or a rock so that it is about three feet off the ground. If there’s no rock or tree that high, find a three-and-a-half-foot stick with a cleft or Y shape at one end that can hold up the ridge pole. Sharpen the other end and push it several inches into the ground so that it will stay upright.

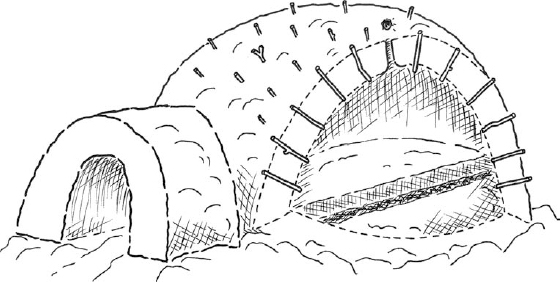

Debris hut

Once you have your ridge pole in place, you lean other, shorter sticks on a slant along both sides of the ridge pole to create a frame that forms a sheltered tunnel underneath. Each stick needs to be touching its neighbor as closely as possible, making a matrix that is close together so that leaves can’t fall through it. If you’re using a stump or rock instead of a Y-shaped stick, make sure to leave yourself an opening at that end, through which you can slide into the shelter. You can weave small sticks or vines horizontally through the slanted walls of sticks to create a basketlike appearance.

Once the frame is done, gather up enough leaves, boughs with needles, mosses, and other debris to cover your framed shelter completely. The leaves and other materials should be five- to seven-feet deep all around your shelter. The leaves will shed any water that falls if it rains and will trap in your body heat as well.

Now, gather pine boughs, if they are available, and lay them inside the shelter as a layer between your body and the earth. If you are lying directly on the cold ground, your body heat will be drawn out of you by conduction, so an insulating layer between you and the earth is essential. If you don’t have pine boughs, just fill the shelter with more leaves and crawl in and out until you have compressed the leaves under you to create a natural pallet. Continue to fill the shelter with more leaves, until the whole cavity is completely stuffed, which in effect insulates you like a sleeping bag. If you have an extra canvas bag, shirt, or other piece of cloth, fill that with leaves, too. When it’s time to sleep, crawl into the stuffing, pulling the leaf-filled shirt over the opening to create a door to help keep the heat in, and get cozy.

Sleeping in a debris hut is an unforgettable experience that connects you with the living earth. You lie in the embrace of the land, asleep in a fragrant nest. You may wake up on a frosty morning and stick your head out of your shelter to see the rising sun reflected off ice crystals. With this shelter-building skill, you will always have a place to rest your head and stay warm, whether in a pinch or because you want to draw closer to nature.

The quinzhee is a winter shelter made out of snow, yet it stays above freezing inside, even when the temperature outside is below freezing. The word comes from the Athabascan language, but quinzhees were made by many peoples who lived in the northern latitudes and had to create temporary snow shelters.

If you’re going to be hiking where conditions may get snowy, you will want to pack a foldable camp or snow shovel, which will make building a shelter much easier. To build a quinzhee, you need to make a big pile of snow, big enough for you and anyone else who is with you to fit under. Generally, about eight feet around and at least five feet high will do it.

If you can find a snowbank or big drift, you won’t need to create as big a pile of snow. If a snowbank is not available, you will need to gather snow and create your pile. This can be a lot of work, and if you don’t have a snow shovel or trowel, you will need to improvise. Snowshoes can be used as makeshift shovels. If you have an extra coat, blanket, tarp, or sleeping bag, they can be used for moving snow. You will need to use your hands and arms to push snow into your receptacle and then carry or drag your snow to your pile.

Quinzhee, or snow shelter

Once you have made your pile, you need to let it rest for at least an hour so that the snow compresses enough so that it is stable and you can carve into it. While you’re waiting for the snow to set, collect at least thirty sticks that are at least a foot long. Once the snow has set, you will push the sticks into the walls of the quinzhee, all around the outside, top, and sides, so that only an inch of each stick is poking outside of the quinzhee. These sticks will help you know how much snow to clear out of the inside of your pile, and they will help you keep the roof and walls at least a foot thick all around.

On the side of the snow pile that is away from the prevailing wind, begin digging into the pile to create an entrance and to hollow out the inside. If you do not have a shovel or trowel, you can use a stick to break up the snow and then use your hands to hollow out and smooth the space inside the quinzhee. Whenever you hit the end of a wall stick, stop digging there and dig toward the next stick. Do not expose more than the end of any stick because the ceiling and walls will be thin and lose strength.

Mark the entrance with an upright stick or flag so that you can find it if you leave the quinzhee and it snows or the wind blows snow drifts over it. The marker will also be a sign to anyone outside if you become trapped inside. If you have a shovel, keep it inside with you should you need to dig out.

Once you are finished hollowing out your shelter’s walls, you can create a channel in the snow on the floor that runs from the entrance to the back wall to make two snow beds. Clear the channel all the way down to the bare earth. It will act as a funnel for cold air, which will drop and run out the door. When you are finished, poke a small ventilation hole in the ceiling.

Before you crawl into your quinzhee, you may be able to find a slab of frozen snow or ice to pull over the entrance after you enter as an improvised door and windscreen.

Sleeping in a sheltered pile of leaves or in a snow cave reminds us that we, too, are animals and that we can exist in a more immediate and direct contact with the earth than we normally think possible. These experiences break down the walls that separate us from the more-than-human world and can help to reframe our ideas and beliefs about what is necessary for fulfillment and happiness. Sleeping in shelters is akin to walking barefoot on the earth. Both practices help us explore and expand our comfort zones and reestablish contact with the wilder parts of ourselves.