OUT OF EXILE

Skills for Coming Home to the Living Earth

My wife, Elaina, is a professional photographer. She was shooting a family reunion at an apple orchard, and the patriarch of the family, a man in his seventies who lived in New York City, was puzzled when my wife encouraged them to pick and eat the apples off the tree, so she could get some action images.

The man asked her, “What do you do? Do you just pick them and eat them? Are they okay to eat?”

My wife assured them that the apples were really good and safe to eat. The man explained that he wasn’t used to seeing food growing on trees.

When Elaina told me this story, I thought, This is what disconnection from nature can look like. Even a tradition as American as picking apples has become, in some places, a distant memory.

A hundred years ago, the world was less populated, and most people were involved in growing or procuring food. Whether tending animals, raising vegetables, or hunting, they had some connection to the source of their food. With the mass migration from the countryside to cities and the growth of industrial farming, fewer and fewer people know where food comes from. Part of rewilding is connecting with our food and getting involved in procuring it in mindful, sustainable, and direct ways.

One of the fruits of mindfulness is an awareness of life’s impermanence. Seasons come and go, people come and go, and life comes and goes. Meditation rests on the practice of establishing the seat of the observer, or witness, and being with life’s ups and downs. Attachment to pleasure and aversion to pain are a natural response to living in a body; all living beings try to avoid pain and prolong pleasure. Nevertheless, all living creatures, by the very nature of their existence, must consume other living things to stay alive. If you contemplate the cycles of life regularly, then you live knowing that all living beings will one day die and that their bodies will become part of the cycle of life from which they originally arose. To live with this awareness changes your relationship to food, from viewing it as the means to acquire energy for survival, to viewing it as a sacred rite that affirms the way all life is connected. There is a reciprocity to be understood within the larger cycle of time, in which we, too, become part of the food chain when we die.

To bring rewilding to food is to practice gratitude for the gifts of this earth that sustain us and to make conscious choices so that what and how we eat sustains the greater good as much as possible. Foraging is the practice of gathering up the food that grows on the land where we live. Most of the time, the foods that we forage are wild, growing without human support. Picking is a little like foraging, except that when we pick apples or peaches or pumpkins, for example, we gather food that farmers have cultivated in orchards and fields.

When foraging for wild foods, we need to follow some ethical guidelines so that our presence on the land increases diversity and abundance rather than decreasing it.

1. For your own safety, never harvest anything you cannot identify with 100 percent certainty.

2. Never overharvest. Always leave plenty of whatever you are foraging.

3. Never forage in polluted areas or beside roads.

4. Leave no trace. Walk carefully and do not trample. Leave places where you forage well-tended and cared for.

5. Be a steward. Do not forage for species that are endangered or in low number.

Foraging and Eating by Season

Each season brings with it sights, smells, textures, sounds, and flavors that create new memories and remind us of years gone by. The circular rhythm of the seasons grounds us as we naturally attune to them in our daily habits, sleep, and diet. We still feel an innate urge to eat with the seasons, enjoying the foods that the land offers up. We crave warm, rich, hearty foods in the cold days of winter and lighter, cooling fare like salads and fruit in the hot days of summer. Some people do tend to eat the same kind of food all year long, feasting often rather than in the fall when the harvest arrives, which can set them up for weight problems, heart disease, diabetes, and even depression, since food affects mood. Spring was traditionally a time of fasting, not because a health coach said it should be but because the store of winter food was gone and there was little left to eat. Today, eating with the seasons is coming back, and we know that eating locally is good for our health as well as the planet’s.

When life was intimately connected with food, the land, and the seasons, many ancient agrarian cultures honored the cycles of the year with cardinal points and holy days around the solstices and equinoxes as well as cross-quarter days, the halfway points between solstices and equinoxes. Christianity subsumed ancient pagan holy days by placing Christmas near the winter solstice, Easter near the spring equinox, and Halloween near the fall equinox. As we have become less connected to the land and our food sources, the origin of these seasonal markers has been obscured and, in some cases, commercialized, yet they still remind us of our planet’s yearly journey around the sun.

My favorite practice for attuning to the food cycles of my bioregion is to forage for food growing naturally on the land. To me foraging is more than acquiring food; it is a way to commune with the generative forces of nature. Like the reciprocal bond in our breathing, in which the life-giving air of the earth is taken into our bodies and assimilated before it is offered back through our exhalation, foraging brings the earth to our bodies in deep and nourishing ways. The physical nutrition energizes and sustains us, and we also receive something else, an embodied connection with the trees, soil, plants, and water that provide this food to us.

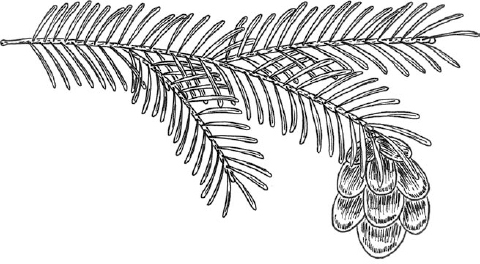

At the Kripalu School of Mindful Outdoor Leadership, the guides-in-training go through seven days of mindful immersion in our forest classroom. Afterward, we all participate in a pine-needle tea ceremony. Each participant forages for a sprig of hemlock pine tree or white pine needles and brings these back to the base camp, where we have a pot of water boiling over a fire. They gently massage the needles or sprigs in their hands to release the oils and then hold the needles up to their noses and take deep breaths. As they inhale the essential oils of evergreen, they are transported by memory. Then, one by one, each person walks up to the cauldron of boiling water and drops their needles into it to create a tea. Someone takes the pot off the fire to let the needles steep, and then everyone gets a cup of forest tea. We hold it, inhaling and focusing our attention on the aroma of the pine-needle tea. Then we sip the tea. We all experience a deep union with the trees. Through this simple tea ceremony, the forest, the sacred space in which we have been immersed for days, enters the temples of our bodies. We are in the forest, and the forest is in us.

The following section on mindful foraging is organized by season. I also share a few of the wild foods I enjoy foraging in western Massachusetts. Take these as inspiration and as examples of what you might be able to find where you live. Every region is different and has its own local food.

Spring: Dandelion Greens, Wild Onions, Garlic Mustard, Fiddleheads, and Eastern Hemlock Shoots

Dandelions (Taraxacum). In the early spring, one of the first things to grow up out of the still cold earth is the dandelion. Considered a weed by many homeowners and the petrochemical industry, the dandelion is one of the most abundant food sources we have. Every part of the plant is edible, and this hardy green is a powerful detoxifier, particularly of the intestines and liver. After eating the rich, heavy foods of winter, eating dandelion greens and flowers is a great way to clean out and prepare the gut for the return of all the abundant fresh foods of warmer weather.

I like to pick a whole bunch of young leaves and flower buds and bring them home to cook or to use raw in a salad. I wash them, then sauté them in olive oil, minced garlic, and salt. You can parboil the unopened flower buds for just a minute or two and then drain and eat them as is, or you can sauté the buds with the leaves. They are delicious! After they open, the yellow flowers are a little more bitter, but you can make a tempura batter and fry them in oil to make fritters. You could also simply sauté them in oil or eat them raw. The bitterness in the leaves and flowers increases through the spring and summer, so they taste best in early spring, before the flowers open.

Dandelion greens

Once you experience the delicious abundance of the common dandelion, you will never look at a lawn the same again. If you are ever in a situation where food is scarce, the dandelion is your friend. But remember: you don’t want to harvest dandelions from a lawn that has been treated with chemicals.

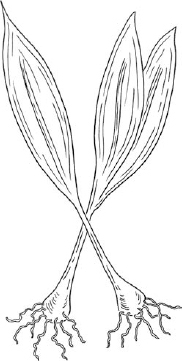

Wild Onions, or Ramps (Allium tricocum). I am fortunate to live at the base of a mountain that is covered in wild onions, or what we call “ramps.” From late winter into early spring, the ramp is one of the first green shoots to poke out of the melting snow. The first ramp shoots let me know spring has truly arrived. Like other onions, these wild ones grow from a bulb underground. The base of a ramp is white with a slight pink hue. The part you eat above the base forms into green, wide, spear-shaped leaves. I cut them off just above the ground — never pull them up by the roots — and fill up a small shopping bag. If you harvest ramps, be sure to leave the bulbs in the ground so they can keep growing and be found again next year. I make sure that I don’t overharvest and always leave about 80 percent of the ramps in any given patch.

Wild onions, or ramps

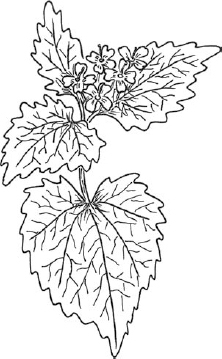

Garlic mustard

Ramps have a delicious, mild, onion-like flavor. You can sauté them on their own or with the dandelion greens and flowers you harvested to enjoy a true foraged spring meal. You can also sauté them and fold them into an omelet, chop and add them to soups, sprinkle them on pizza, and even make a pesto with them.

Wild foods like ramps are healthful and precious. Unfortunately, in some places, ramps have been harvested so heavily that the old ramp beds are disappearing. So, if you find wild ramps on your land or in a public place, keep an eye on them. Be discerning about whether you should take any at all. If you can, be an advocate for them and raise awareness about sustainable foraging and conservation.

Garlic Mustard (Alliaria petiolata). Garlic mustard is an invasive weed that grows in abundance in New England and other parts of the country. Yet it is also delicious and highly nutritious. It crowds out native species, so you can feel good about harvesting this plant — it doesn’t look like we’re ever going to run out of it. Garlic mustard is easy to identify. It grows two to three feet tall and has alternate leaves. The leaves that grow near the bottom of the plant are heart shaped with scalloped edges that become pointier as they grow toward the top, where a cluster of small white flowers emerges. The leaves, which are the main edible part of the plant, tend to taste better (less bitter) if harvested before the flowers bloom. Garlic mustard leaves can be eaten in salads, used as a garnish, or in place of lettuce on a sandwich. You can also make a delicious pesto out of them. I love to sauté garlic mustard leaves with dandelion greens, ramps, olive oil, minced garlic, and a touch of salt. Delish!

Fiddleheads (Matteuccia struthiopteris). Fiddleheads are the unopened leaves of ferns in early spring. Nearly all ferns have fiddleheads, but it’s the tops of the ostrich fern that you want to harvest, as not all fiddleheads are edible. Ostrich fern is an abundant native species in North America. Fiddleheads are easy to identify, although the window for harvesting is small, usually in late April or early May where I live in Massachusetts. I know a few places where they grow in abundance, and heading out on a Sunday afternoon to gather them is one of the great joys of spring for our family.

The fiddleheads themselves are coiled up in a circle about the size of a quarter and are good for harvesting when they are about two to four inches off the ground. Fiddleheads can be identified by the following characteristics: they have a bright green stem with a deep green groove on the inner side and a brown, feathery, paperlike material covering the head, which begins to fall off as they grow. There is at least one fern, bracken, which looks similar, but it is toxic — so it is best to go with an experienced forager your first few times out.

Bracken fiddlehead

Ostrich fiddlehead

To prepare fiddleheads, rinse them thoroughly with cold water in a colander and pick off any of the brown papery material. Boil or steam them for ten minutes. You can eat them with butter and salt, or add them to a sautéed dish of mushrooms or other vegetables. Just remember to always boil them before you sauté them. Fiddleheads have a mild flavor, a bit earthy, somewhere between spinach and broccoli. I like to toss some fresh ramps in with my cooked fiddleheads, since they both come up around the same time.

Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis). Another spring favorite for delicious foraging comes from the eastern hemlock tree. These beautiful and elegant conifers have flat, short needles that are dark green on top with two blue-white lines running the length of their underside. In the springtime, the eastern hemlock produces bright green needle tips that are soft and edible. You will notice them as you hike through the forest because the tips are so much lighter and brighter than the older needles on the trees. While hiking, you can pick and nibble them as you stroll under the watchful and gentle boughs of these beautiful trees. Close your eyes and say a few words of gratitude to the tree before and after you harvest its new growth.

Eastern hemlock

The young needles have a lemony flavor and are high in chlorophyll, tannins, and vitamin C, which has antioxidant properties. In other seasons, the needles can be made into a tea. Choose a couple of tiny twigs, about the length of your index finger, and before steeping the needles, rub them between your hands to release the aromatic oils. Then cup your hands and bring them up to your nose to inhale the aromatic oils. Drop the needles into water that has been boiled and let them steep for five to ten minutes. You might want to strain the needles before you drink the tea, but you can also use your teeth to strain them as you drink. After a mindful stroll through the forest, a cup of hemlock tea is a beautiful way to bring the essence of the forest into the body and to awaken the sense of both taste and smell.

You may have heard of poison hemlock, an infusion that is credited with killing Socrates. But poison hemlock is not an evergreen tree like the eastern hemlock. Poison hemlock is an herbaceous plant without needles; it sprouts white flowers that look a little like Queen Anne’s Lace. You cannot confuse the herbaceous hemlock plant with eastern hemlock tree needles.

There are many other delicious and nutritious plants to forage in the spring. I recommend getting a field guide or app to learn about them. You can also take a picture of a plant you’re drawn to with your phone and find out from the internet if it’s edible once you get home. Foraging is a way to reconnect with the wild, free, and abundant foods all around you, and it provides a powerful shift in perspective. You see that the living earth is abundant. A single oak tree can produce thousands of acorns, while a wide-open lawn can contain thousands of blooming dandelions. Many people who believe that food and resources are scarce overlook the abundance of nature’s bounty. What a joy it is to receive the nutrition that the earth provides for us each and every day. A sip of hemlock tea, a dish of sautéed dandelion, and a piece of sourdough bread spread with ramp pesto can teach us an important lesson: the earth loves us and wants us to be happy!

Summer: Wood Sorrel, Staghorn

Sumac, and Wild Blueberries

Wood Sorrel (Oxalis). The wood sorrel is one of the most adorable plants growing on the earth. It is widespread, so you can find it in almost any yard. Wood sorrel is a small weed with three heart-shaped leaves and a small yellow flower when it blooms. Sometimes wood sorrel is mistaken for clover, which is also edible. The wood sorrel’s heart-shaped leaves have a tart, lemony flavor. You can nibble the leaves raw or sprinkle them on salads, soups, fish, or pasta. It is one of my favorite wild edibles, and it is the first one I taught my children to pick. My daughter, Cora, loves to find what she calls “lemon clover.”

Wood sorrel

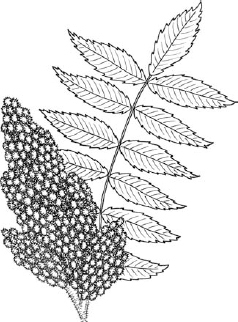

Staghorn sumac

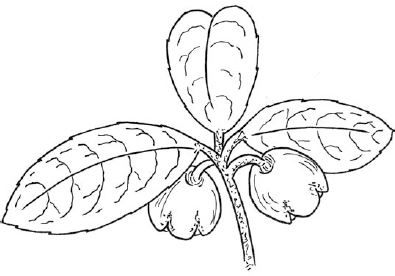

Staghorn Sumac (Rhus typhina). Staghorn sumac is a native shrub in New England that is found in sandy or rocky soil. It is not to be confused with poison sumac, which has greyish-white berries that grow and hang down in clusters. Staghorn sumac produces large, deep red berry clusters that point up to the sky, and its branches have a velvety surface, like that on newly grown deer antlers. Staghorn sumac often grows in disturbed areas, open lots, and along fences and the edges of open spaces. The red berry clusters can be picked in late summer and soaked in cool water to make a pink “sumac-ade,” a delicious tart beverage that tastes a lot like lemonade. The berry cones contain a lot of vitamin C. You only need to soak the berry clusters for five to fifteen minutes for the water to be infused by both the color and flavor of the berries. The longer the berries soak, the more sumac flavor. You can add your favorite sweetener to taste. I prefer maple syrup and like to drink my sumac-ade over ice. This was a staple drink in New England for hundreds of years, before imported lemons became widely available. Because sumac is such an easy plant to identify, forage, and prepare, it is another great food to forage for beginners and children.

Wild Blueberries (Vaccinium angustifolium). Wild blueberry can be found on well-drained, sandy, highly acidic soils. In western Massachusetts, I often find it on mountaintops and hills along my favorite hiking trails or growing near the edges of ponds and lakes. There is nothing quite so fine to forage as you stroll through the woods on a hot summer day as the delicious and highly nutritious wild blueberry. The lowbush blueberry is usually a short bush with small, dark green leaves in summer that turn brilliant orange and deep red in the fall. The berries are smaller than the cultivated berries sold in stores and dark blue in color. Extremely high in antioxidants, wild blueberries are considered a superfood.

Wild blueberries

At my house we planted two lowbush blueberries along with six highbush blueberry plants so that we’d have them growing near our home as well as up the mountain. My kids love going in the backyard every day in August to check on the crop and pick them for a snack. You might also have other kinds of wild berries near you. Blackberries and raspberries are also common throughout the United States. Both grow wild and have no poisonous look-alikes.

When my wife was in the early stages of labor with our daughter, Cora, we went blueberry picking at a local farm so she could be outside and moving around. Every August around Cora’s birthday, we now go to that same place and pick blueberries. It’s a sweet tradition that connects us to that special moment in our lives and the land on which it happened.

Berries are a seasonal, summer food. If you don’t have wild blueberries near you, see if there are places where you can pay to pick. You can get a lot more berries for your money at a local farm that is open to the public than you can at the market.

Fall: Apples and Hickory Nuts

Apples (Malus pumila). Fall is by far my favorite season. As someone who runs hot, I am often uncomfortable in the summer. I love when the first winds of autumn begin to blow, and I know I can look forward to cooler mornings, less heat and humidity, and wearing layers. Fall is also a time when many wild foods are ready for harvesting and the growing season comes to an end. In pagan cultures, the year draws to a close around the time of the autumn equinox, which is called “Samhain” in the ancient Celtic culture. Many fruits, vegetables, and tree nuts are harvested in the fall, the last chance to gather what is needed for the long dark of winter.

Picking apples outdoors in the fall is an easy way for people to dip their toes into sourcing food for themselves. Of course, picking apples cannot be considered wild foraging, as apple orchards are heavily managed. Pick-your-own farms, which are open to the public, grow many different varieties of apples in their orchards. What a wonderful feeling it is to get outside in the crisp autumn air, picking and eating apples, whose cool, crisp, and refreshing qualities reflect the characteristics of their season of harvest. Apples can be eaten off the tree, pressed into juice or cider, baked in pies, or cooked down for sauces and butters.

I’ve been foraging for a long time, and I still love spending an afternoon in late September picking apples with my family. It is truly quality time, away from the noise and stress of modern life, with only the sound of the wind and the colors of the earth for your entertainment. There is a purity and an innocence about picking, and conversation and spontaneous play rule the day. Like any kind of mindful time spent outside, sourcing your own food is nourishing on many levels. That you get to fill your home with the smell of apples and cinnamon baking is a wonderful benefit.

Hickory Nuts (Carya ovata). Throughout my life I have been drawn to certain trees. One of my favorites is the shagbark hickory. When I was a kid, my dad would gather hickory limbs that fell on our land and chop them into chips, which he would use to slow cook and smoke pork shoulder. The smell of hickory smoke wafting on a warm breeze and the hickory-smoke flavor that seasoned the food were pretty special.

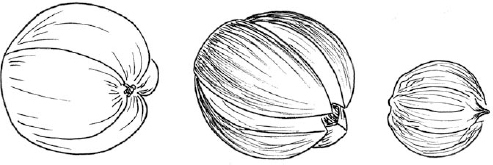

Hickory is a tough, strong tree. Its wood is very hard and dense, and it has long been used to make tool handles and baseball bats. Shagbark hickory bark peels off the tree trunks in long, vertical strips, giving the trees their shaggy appearance. Hickory trees produce nuts that fall to the ground in September and October. Of the different varieties of hickory trees, shagbark hickory nuts taste best. The nuts are oval, about an inch to two long and a little over a half inch to an inch wide. They’re covered in a green casing that is sectioned in four quarters. When the nuts are ripe, the outer casing comes off easily. Hickory nuts are edible directly out of the shell and taste similar to a pecan or a walnut. They have a slightly sweet nutty flavor and can be used in place of either pecans or walnuts in your favorite recipes. Before almonds and other nuts grown in California were transported nationwide, gathering hickory nuts in the fall was a classic New England pastime. Hickory-nut pie was a staple on the Thanksgiving table of many New Englanders in the 1800s and early 1900s. Most people today have no idea that hickory nuts are an edible and abundant food source.

Every fall my kids and I enjoy at least one afternoon on a hickory-nut ramble. I know a few choice locations where big hickories drop lots of nuts. We bring canvas bags with us, as well as a few good rocks for breaking open the nuts. After we have collected a bunch, we like to sit down with our backs against the stable and comforting hickory trunks while we break open the nuts with our rocks. My daughter loves it. All the time kids are told not to be rough and not to break things, but kids love to smash stuff sometimes — and so do adults.

Hickory nuts

Wherever we go, my kids know they can gather hickory nuts and have food. They’ve also begun to develop a relationship with that life-giving tree. This is one of the great gifts of foraging, the way that intimacy with specific plant species brings us closer to the more-than-human world and allows us to perceive the great diversity of living things. Rather than seeing a sea of green or a blur of brown, we become aware and begin to differentiate the unique qualities of the different plant communities we share the earth with.

Winter: Jerusalem Artichoke, Wintergreen, and White Pine

Jerusalem Artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus). A relative of the sunflower, Jerusalem artichoke is a native of eastern North America that has become naturalized in many other locations. First Nation peoples used it as a major food source. The edible part is the tuber, which stores its energy underground. The flowers are similar to sunflowers but smaller. Unlike sunflowers, Jerusalem artichoke tends to grow in patches. I have a patch of them in my backyard. Their stalks usually grow up to seven feet tall by the time late September comes around. You can harvest the tubers in the colder months, from late October through March, and eat them raw, roasted, steamed, boiled, or mashed. You can even make them into pasta, although I have never tried it myself. They have a crisp texture when eaten raw, similar to water chestnuts, and their flavor is similar to artichokes, which must be how they got the name.

Jerusalem artichoke

Jerusalem artichoke is one of the best wild foods for winter foraging because, like potatoes, they provide a substantial meal that is delicious and filling. They are also a great comfort food, something you can throw in a roasting pan with other vegetables, fish, or meat for a tasty meal on a cold winter’s night.

The one trick with Jerusalem artichoke is that they tend to be difficult to identify, especially in the middle of winter when the flowers are gone and the leaves have shriveled or blown away. One of the skills of foraging is remembering where edible plants are from one season to the next, when the food is ready to harvest. A stand of Jerusalem artichokes will come back year after year if you don’t dig up all the tubers. They are incredibly resilient. Some home gardeners avoid growing them because they can be invasive.

Wintergreen (Gaultheria procumbens). Winter in New England is cold, long, and often dark. The truth is, there is not much to forage in the wintertime in New England. Native American tribes who lived here before the European invasion lived off the stores from their fall harvest and summer hunting. When food grew scarce, they hunted deer, went ice fishing, and sometimes resorted to eating the inner bark of trees such as birch or hemlock.

But dotting the snow with tiny flecks of red on this stark beautiful landscape is a truly remarkable edible plant, the wintergreen. The wintergreen’s small leaves have a dark green, leathery appearance. The wintergreen’s berries are red, about the size of a pea. They mature in the fall, but their taste improves after being frozen. The leaves can be boiled to make a tea and also nibbled with their delicious berries. Wintergreen has a light, bright, refreshing flavor similar to black birch but slightly more minty. Wintergreen grows in low acid soils; I often find it near the tops of the ridges in the Berkshires, along some of my favorite hiking trails. There is something so simple and beautiful about the red and green of winterberry on a canvas of pure white snow.

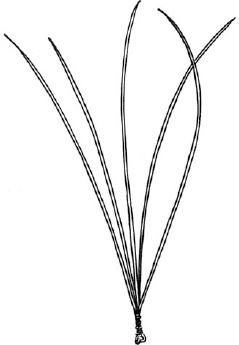

Eastern White Pine (Pinus strobus). In the depths of winter, the eastern white pine, like other evergreens, holds on to its green needles. Rich in vitamin C, like the eastern hemlock, the needles can be used to make a comforting tea. The eastern white pine is a prosperous and beautiful member of the forest community in New England. Its needles grow in packets of five, which is an easy way to identify it since white has five letters. The five needles of the white pine are also symbolic of the five nations of the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) Confederacy, which chose the white pine to be the great “Tree of Peace.” The weapons of the warring tribes are said to have been buried under the Tree of Peace when they joined together as one. The Iroquois culture and form of governance are known to have inspired our founders and the representative democracy they established for the United States.

Wintergreen

To make a bright, citrus-pine-flavored tea from white pine needles, you will want to gather at least twenty packets of white pine needles. Rub a couple of the packets between your hands to release the pine resin, as you offer a gesture of thanks to the trees for this provision. You can drop the crushed needles into a pot of freshly boiled water and allow them to steep for five to fifteen minutes, although I like to cut them up into smaller pieces to help release the oils before steeping them. Strain the needles from the boiling water and pour the tea into a mug. Before sipping, hold the cup up near your nose and take a few deep inhalations. Drink as is or sweeten with maple syrup or honey. Enjoy!

Eastern white pine

In the programs I lead, I often wait to introduce foraging until people have had a few days to relax and begin feeling comfortable on the land. Folks have a full seven days in our hemlock forest before they experience their first tea ceremony. They have been practicing mindfulness every day, often sitting against the trunk of a hemlock in the early morning, as they slow their breathing, take in the earth through all of their senses, and watch as a new day emerges from the night. Through this process, the trees, stones, and other members of the forest community become a part of their world, so on the seventh day, when we make hemlock tea and bring the essence of the forest into our bodies, the experience can be unexpectedly powerful.

During our first training, my co-trainer Mark turned to me in front of the group and handed me the first cup, which he invited me to offer to the forest. Honored and touched by his kind gesture, I took the cup and turned to look out at the forest. My eyes immediately landed on the bark of a shagbark hickory behind the tent we were gathered in. Though I had looked upon this tree many times and have a special affinity for hickories, this time I saw in the bark the face of an old, bearded man with a long nose. I was stunned, overcome with wonder and emotion. It felt to me in that moment that the forest was very much alive, aware, and awake to our presence, and that this was its way of saying thank you to us.

The intention that we set for all our practices, including rewilding, allows the practices to have the greatest impact. It’s one thing to eat a berry or drink tea because you are hungry and thirsty, but it’s another to recognize the miracle of a berry and the majesty of a tree and to invite their essence into communion with you. It is the consciousness we bring to our mindful rewilding that makes the difference between pure survival, man against nature, and true union, healing through intimacy with the great web of life that unites us all.

Many people complain about the cold of winter, but I find that the landscape opens more fully to me in the winter months. Lush forests are easier to navigate after the leaves have fallen, and one can move more freely on the land without being bothered about ticks or mosquitoes. The woods behind my house is bordered by a small floodplain, which is practically impenetrable in summer. But in the winter, the undergrowth recedes, and I can traverse the wetland more easily. The marsh grasses and swamp trees provide a crucial habitat and sanctuary for many wild animals who live there year-round, including bobcats, deer, bears, foxes, coyotes, fishers, muskrats, raccoons, river otters, turkeys, and a whole host of birds who nest there each spring. In addition to the spaciousness of the land, the snow reveals the comings and goings of the more-than-human world as animals leave their tracks in the snow.

A few winters ago, when my son, Stryder, was just four years old, he and I went for one of our weekend walks in the woods behind our house. We crossed Coyote Bridge and the frozen marsh, making our way to the higher ground at the foot of the mountain, where we found two sets of very large, side-by-side coyote tracks. It was snowing that morning, and about a half inch had already fallen. These tracks were made in that newly fallen snow, which meant that these two large coyotes had moved through this area in the last thirty minutes or so. I told Stryder this and showed him the tracks. His eyes widened. I showed him how coyote tracks have four toe pads and how the back two toes tuck in close behind the front two. Coyote tracks tend to have a more oval shape than bobcat tracks. Stryder is eight years old now, and before we head out into the winter woods, we review the animal tracks I’ve taught him. I quiz him and his little sister, Cora. With time, both are becoming familiar with the tracks we see on the land, and I believe their familiarity with the presence of the more-than-human world supports their bond with our woodland friends.

In the spring, when the black bears emerge from their long winter slumber, we see their tracks in the muddy, wooded path next to our house. I’ve shown the kids that bear tracks have five toes, and anytime we find bear tracks, they look around and usually ask to go back in the house! Knowing that these large wild beings roam the land invokes a natural and necessary respect. Rather than clomping through the forest as if we were kings of the earth, we can acknowledge our wild relatives by acting with respect, humility, and an awareness of our place in the web of life.

Tracks tell us that even though we may not see animals moving on the land, they are out there, avoiding detection, blending into the shadows and wooded corridors that weave through the human world. Paying attention to animal tracks, signs, and scat is another way to reconnect with the wild.

The tracks or impressions that animals leave can be seen in mud, snow, sand, and leaf or pine litter. They make these impressions with their paws, hooves, bellies, snouts, tails, talons, and wings. Snow and mud are the easiest surfaces on which to see tracks, although with practice, or what master tracker Tom Brown Jr. calls “dirt time,” you will begin to notice tracks and trails in other types of terrain. Each track tells a story, of an animal and its life and sometimes its death.

Black bear track

Signs that animals leave can be the scrapes on a tree from a buck’s antlers or a bear’s claws, the nibbled ends of grasses made by a rabbit or other foraging critter, or the holes hollowed out of a tree trunk by a woodpecker. Signs could also be hickory or walnut shells chewed open and left on an old stone, piles of pine cone litter left by a squirrel, or the turkey carcass and feathers and bones left by a pack of coyotes. The signs left by the more-than-human world are varied and diverse. They can help us open our minds, hearts, and senses. We can become aware of the life and death struggles as well as the beauty all around us and within the folds of the living earth.

Scat is the fecal matter animals leave behind. Each animal’s scat is unique, and each species’ scat has certain characteristics that can be helpful in identifying that animal. Bear scat tends to be large and is deposited in a pile, often with lots of seeds visible, whereas deer scat looks like pellets anywhere from a quarter to a half inch in length, although this can vary. Foxes and coyotes tend to leave more elongated stools, often with fur and small bones visible, depending on the prey the animal last ate.

This book isn’t intended to be a comprehensive guide to tracking, as there are many great field guides you can get to help you identify the animals in your area. What I would like to offer you here is a way to begin thinking about the tracks you encounter on your morning or afternoon walks or out on the land for your nature meditation. Like all of the skills you are learning as you rewild your life, tracking is one that improves over time, with one type of track laying the foundation for identifying others. For instance, you might begin by learning to identify the hoof prints of the white-tailed deer or the hopping pattern of the common but very cool grey squirrel. Once you know one basic track, you can begin to learn about the varied tracks that animal makes when its gait or speed of movement changes. You’ll also learn the straddle (the distance from left to right between the tracks) and the stride (the length between individual tracks). Each of these measurements can be helpful in identifying the kind of animal you are tracking, and they also tell you something about what the animal was doing at the time he made the tracks.

You may begin to notice that an animal you are tracking has a recurring daily pattern of movement. Animals tend to be creatures of habit, moving along the same paths on a regular basis, often creating paths, or runs, you can become familiar with. Once you recognize these patterns, you also have a responsibility to cause as little disturbance as possible to the animal or animals. If you know the daily patterns of a small herd of white-tailed deer, for instance, you can sit in a place close enough to observe them but stay far enough away so that your presence does not alarm them.

One of the great rewards of tracking is becoming familiar with both a single animal you share the land with and the various other species. Birds leave tracks, signs, and scat, and because they are easy to observe during the day, they can be a wonderful creature to begin to track. In the springtime, when backyard birds are nesting, you may get to know a single bird or a family of birds. Because a single nesting family stays in one location, you can get to know the individual birds as well as characteristics of that species. The same is true for squirrels, rabbits, and other common backyard animals. They are not as elusive as the nocturnal creatures we often know are present only by the tracks they leave behind. I love keeping tabs on the family of chipmunks living under our front stairs.

When you get to know individual animals who live near you, you also will become familiar with the daily cycle of predator and prey. Even though it can be shocking or sad to lose one of these animals you enjoyed observing, it does help you gain a greater understanding and connection with the living earth.

Animal trails — or runs, as I mentioned earlier — reveal the regular patterns of movement of a certain animal or species. These trails often look like subtle pathways through tall grasses or tunnels underneath thick-growing bushes. They can also look like a trail running through the land, with multiple tracks layered on top of one another.

To more easily find the runs left by animals, it can be helpful to get down low and see the landscape the way the creature you are tracking would see it. Animals see the world from a much different perspective than we do. Getting down on all fours can help you begin to see through their eyes and perhaps even begin to anticipate where they might be heading and why. While you are down there, you can also look for any signs of browsing — such as grasses or other plants that have been chewed, nibbled, pulled up, or otherwise eaten. You may also see smaller trails, runs, or tunnels down on the ground or under the snow, which would be left by mice, voles, or other small rodents that feed larger predators. Perhaps you will also see ants, worms, and other tiny, tiny creatures moving through the avenues, trails, and runs beneath the grass. There are truly worlds inside of worlds all the way down.

ANIMAL-TRACK MANDALA MEDITATION

When you find an animal’s tracks, get down low on the land so you can look at it closely. Kneel, squat, or lie down on your belly. Get close enough so that you can see all of the features of the track — the depressions from the individual toe pads or claws, the punches in the soil from the nails, and any variations in the depth of the tracks.

Whether or not you can identify the animal who made this track, take time to study the track intently, as if it were a mandala designed to deepen meditation. As you gaze at the track, let go of whatever else you might be doing. Let your attention be single pointed, as you scan all of the small features. Smell the earth and the air around you, and notice if you can pick up any scents left behind by the creature. Some animals, like fox, leave a musky scent. Imagine the animal stepping on this exact piece of earth before you were here. Open your awareness to the presence of this animal, feel the animal here in this space with you, and allow your awareness to rise up to the sky, as if you were a hawk soaring. Stretch your mind with this awareness and sense where this animal might be at this moment.

Then take a few breaths and feel how the earth underneath you and the air all around you is like an ocean that connects you with the spirit and presence of this wild being. Take a moment to express gratitude for the gift of this track and respect for the thread that connects you with this creature.

Make time to be completely present with each track. This skill takes time to improve. Try not to get frustrated if you find it hard to find tracks or if they are difficult to identify. In hunter-gatherer cultures, these skills were learned from early childhood. You wouldn’t expect to be fluent in a foreign language after learning a few words. Keep a field guide for animal tracks with you and keep learning.

Rewilding offers many pathways for connecting with the miraculous life-forms on this good earth, from walking with awareness and sharpening our senses, to becoming intimate with our land and harvesting sustenance from it. Through mindfulness, we come to the living earth as ourselves, as we are in this moment. We come back into relationship with the earth through a renewed relationship with ourselves as sentient, sensitive, and highly adaptable.

We sit in meditative awareness, receiving breath and offering our life presence to evolution’s unfolding. What happens when our tailbone rests directly on the earth and we take in the smell of dried white-pine branches crackling and popping in our small fire? What happens when we sit in stillness and reverence and watch the afternoon slip into evening? Who are we who bring this consciousness to the earth? Could it be that we ourselves are the planet, that we are biped planetary neurons giving the living earth the opportunity to experience itself through our complex nervous systems? We hold the great pendulum of our own possibility, the possibility of a peaceful and harmonious presence on this planet. When we connect with the living earth, we are no longer at war with the life systems that support us; instead, we become their dedicated caretakers. When we bring our present-moment awareness into the woods and fields and reintroduce ourselves to the more-than-human world we have been missing for so long, life as we know it will change.