Nepal is one of the poorest countries in the world. It runs neck and neck with Bangladesh in a race for the poorest country outside of Africa. The average annual income is about one dollar per day. Nepal does not have a public schools system, and the national literacy rate is below 50 percent. Although it has more than fifty distinguishable ethnic groups, each with its own language or dialect, most of the local-regional languages are preliterate. (Niru told me the Rai had a written language “in ancient times,” but it was lost.) Despite its poverty and cultural diversity, tolerance and harmony among its different ethnic groups and castes has generally been the way of Nepal.

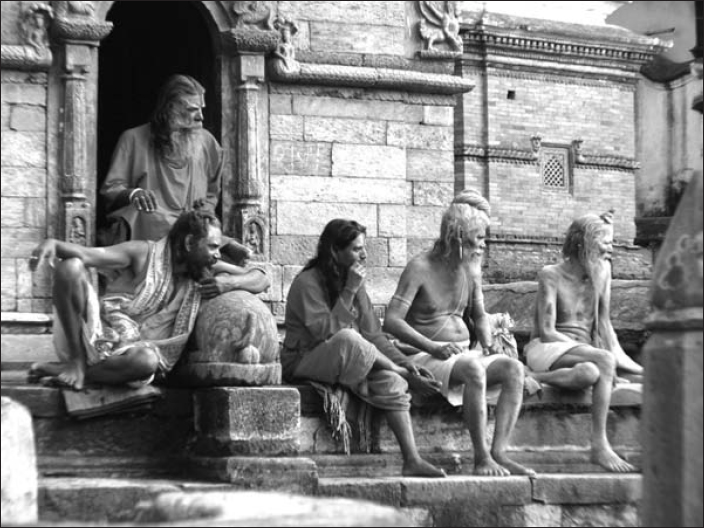

Nepal became an object of fascination in pop culture in the 1960s and '70s. A lax attitude toward hash and pot smoking combined with the custom of hospitality and tolerance by the Nepalese Hindu-Buddhist culture encouraged hippies and spiritual seekers to come to Katmandu. “Freak Street” near Thamel (the old town and tourist center of Katmandu) became an international destination for head shops. Local gurus and holy men were happy to take on paying students and devotees from the West. (My two favorite gurus, were the Milk Baba, who consumed no food or drink other than milk during his adult life, and the Penis Sadhu, whose discipline was to lift with his penis a fifty-pound concrete block tied to a silk kata. The Penis Sadhu died a couple years ago, but the Milk Baba may still be visited at Pashupatinath.)

Sadhus at Pashupatinath

Love and peace, like the Beatles preached in “All You Need Is Love” and “Magical Mystery Tour,” seemed to hip and enlightened Westerners to be embodied in Katmandu. Bob Seeger's 1975 hit “Katmandu” (“Goin' to Katmandu, that's what I'm gonna do”) nailed the sentiment that Katmandu was where it was at.

The pop-culture view of Nepal was not entirely frivolous. Spirituality is a fundamental cultural value in Nepal. Gurus gather followers and may become cultural heroes as their popularity and renown grow. This is in contrast to the United States, where cultural heroes who gather devoted followers are more likely to be AM radio ranters than authentic spiritual leaders. The Rush Limbaughs of our culture gain popularity with divisive and mean-spirited rhetoric. A guru gains renown in Buddhist-Hindu culture through promoting the message of peace and love and encouraging followers to greater spiritual enlightenment.

In the 1960s and into the 1990s, Nepal was a beacon of peace in the sense that Hindus, Buddhists, Moslems, Christians, and all the different ethnic groups lived in peace. Religious coexistence, rather than religion-inspired violence, has been the guidepost of Nepal's history. Political strife and caste oppression are part of the country's history as well. There were coups and countercoups for and against the monarchy during the 19th and 20th centuries. But peaceful coexistence among its diverse ethnic population had been the norm since facing down the British invaders in the 19th century. The Maoist revolt against the kingdom, however, transformed Nepal from a peaceful Shangri-la to another place of terror and violence on the world stage.

In the 1980s and '90s, the trekking-tourist industry grew rapidly. Many Nepalese were lifted out of poverty in the tourist destination areas such as the Katmandu Valley, the Khumbu along the Base Camp Trail, Langtang, Pokhara, and around the Annapurna Circuit Trail. But the boom was short-lived and busted by the end of the '90s. The 2003 Jubilee celebrations caused an uptick, but the truce between the government and the Maoist rebels ended after the celebrations, and the return to violence again scared off the tourists, particularly Americans, because President Bush declared the Maoists an international terrorist organization.

In October 2004, while I was mucking around in Tribhuvan International Airport dealing with lost bags, friend Elliot was waiting for me outside the airport when he saw an explosion in downtown Katmandu. The Maoists had rolled three hand grenades into an office building. That was the closest anyone in my trekking groups came to experiencing violence or being directly affected by the civil war in Nepal. But fear of violence and the political instability of Nepal frightened some friends away from joining expeditions.

Beginning in the late 1990s, the Maoists claimed territorial rights over certain trekking trails. These trekking trails became revenue sources for the Maoists. Armed bands would block trails and require trekkers to pay a fee to use the trail. The leader of the band would give the trekkers a lecture about politics in Nepal and then issue each trekker a certificate declaring the fee had been paid so other Maoist bands would not collect the fee a second time. If a trekker didn't have enough money to pay the fee, the Maoists would take a camera, climbing gear, down jackets, or other valuable possessions. The fee was generally around $100, but after the U.S. government declared the Maoists international terrorists, Americans were required to pay double the amount of all other nationals. When the Maoist insurgency was at its worst, I wrote “Canada” on my trekking duffel with a Sharpie, just in case.

The Maoists were unsuccessful in penetrating Sherpa communities in the Khumbu, so, happily, I never had an encounter with one of their armed bands. Every Westerner I met in Nepal who hiked the Annapurna Circuit from the mid-90s through 2006 had a Maoist encounter. In the Khumbu, what we encountered was an ever-increasing military presence. Each year, we passed more government soldiers on the trails and had to cross through additional military checkpoints.

In Katmandu, the king would periodically impose a curfew on citizens, which usually didn't apply to tourists. Walking back to our hotel in 2004 after a night out with Nepalese friends, Briggie, Elliot, and I had to endure the hard stares of young soldiers with loaded carbines. They were understandably resentful that we were allowed to walk the streets of Katmandu freely, while our Nepalese friends had to skulk down alleys and hide from the soldiers, or risk arrest or a beating. Most of the army recruits during the civil war were young uneducated village boys. Their training was poor, evidenced by the fact that they lost most of the pitched battles against the Maoists, and the allegiance of the Nepalese people eroded and eventually swung in favor of the Maoists. So it sent a little shiver down my spine when that young soldier stepped out in front of us, pointing his rifle at us, while intently eyeballing Briggie, a tall, slim, blond, blue-eyed South African. But with a sneer and jerk of his head, he let us pass.

In 2004, the first year I organized a trekking group, five people who had planned to join the group chickened out due to State Department warnings. In 2006, two women canceled two days before departure because of riots against the king breaking out in Katmandu. Of course, we are all prisoner to our own experience regarding fear of crime and violence. South Africans Elliot and Briggie were highly amused at American fears of violence in Nepal. Even with the civil war raging, they found Nepal much safer than Johannesburg, which has one of the highest street crime rates in the world.

I have never been the victim or even seen any real violence in Nepal, but what I did experience was amazement and disbelief at the change in the Nepalese attitude toward violence as the Maoist rebellion became a full-fledged civil war. Just before my first visit to Nepal in 1995, a Nepalese guy killed a European in a bar fight in Katmandu. The entire nation was in mourning when we arrived because of the felt national disgrace and sorrow over a guest of Nepal being killed. In the ten-year civil war, from 1996 to 2006, an estimated 12,800 Nepalis died. I found it unbelievable that the Maoists and the government could have brought such a degree of fear, death, and destruction to a nation that mourned so soulfully over the death of one person two years before the war began.

In 2006, as the war reached its climax, a friend was brutally beaten in Katmandu. Raaj is a native Nepali, but grew up in India, has long hair, owned a tea shop in Katmandu, and is the leader of a rock band. He looks like a dissident, but he was not a Maoist, just a guy who loves Western rock music. One night when walking home after a gig in Thamel, Raaj and his band mates were jumped and beaten by “royalists.” Raaj's arm and nose were broken. When I saw him a month or so after the beating, of course I was upset for him, but I also found it hard to accept that such a thing could happen in this country that had been a beacon of peace in a violent world just a few years before.

The assessment of most of my educated Nepalese friends is that, although the Maoists started the war and brought death and terror to Nepal, it was the arrogance, incompetence, and brutality of King Gyanendra that inspired so many to join the revolt to bring down the government. Gyanendra, King Birendra's younger brother, became king after Crown Prince Dipendra shot and killed his parents and siblings at the dinner table on June 1, 2001, after arguing with his parents about a girlfriend. Dipendra turned the gun on himself and was in a coma for three days before dying. As King Birendra's eldest son, Dipendra was legally king for the three days he spent in a coma.

King Birendra had been a fairly popular king. Although the Maoist revolt began several years before Dipendra's patricide, it was largely contained in the rural west. After Gyanendra was crowned, he vowed to crush the rebels with the overwhelming military superiority of the army. Instead, the army repeatedly lost battles to the guerrillas and the rebellion spread across the country as Gyanendra's heavy-handed rule turned more and more Nepalese against the king.

The Maoists were not popular among my educated Nepalese friends in Katmandu. One friend compared the Maoists to the Mafia with a political agenda. He told me his experience was typical. The Maoists had a cadre member in my friend's village, a suburb of Katmandu, and the local Maoist representative required every villager to contribute money or food to the Maoist cause. Any family that refused to contribute to the Maoists risked having their house burned down, being beaten, or even killed. To an American like me, who had lived in Chicago, it sounded just like a protection racket.

Another friend, who managed a hotel in Katmandu, told me the hotel paid extortion money to the Maoists in order not to be hassled or to have a hand grenade tossed into the lobby. A third friend, whose son was studying medicine in the United States, had to hide that fact from her neighbors for fear the local Maoist cadre would think she could pay extortion. She feared the Maoists would reason that, if she could afford to send a child to study in America, she could afford to contribute to the cause. Her son was on a full scholarship, but she doubted the Maoists would care about that.

No, the Maoists were not seen as saviors by the educated classes or those benefiting from the developing tourist economy. They were very popular, however, among the poor in western Nepal, which had no tourist industry and was neglected by the government. Over time, the Maoists' popularity increased across different sectors of the country's underclasses. The elite and high castes dominated the parliamentary parties. With the Maoists, the poor of Nepal finally had a party that claimed to represent them, and the Maoists were the only party demanding that the despised King Gyanendra be deposed.

By 2006, the country was so weary of the war, furious with King Gyanendra, and frustrated that the Parliament had been unable to establish a road map to peace that thousands took to the streets in Katmandu. Gyanendra tried at first to suppress the demonstrations with force, but the demonstrators refused to back down and thousands more joined the demonstrations against him. The day before my group arrived in October 2006, the king agreed to give up executive power, the Maoists agreed to participate in elections, and the Parliament agreed that a new constitution would be written. By May 28, 2008, Gyanendra was deposed and the 500-year-old Shahi dynasty came to an end. The new constitution created a parliamentary democracy, and the Maoists won a plurality of the vote in the first election. The chairman of the Communist Party of Nepal (the Maoist's formal party name), a man known as Prachanda, was elected prime minister and thus became the first democratically elected Maoist leader of any country.

World leaders wrestling with problems of insurgencies and civil unrest could learn from Nepal. It took ten years, but the issues tearing the country apart have been largely resolved. Nepal rid itself of an oppressive executive power, the king, and incorporated the insurgents, the Maoists, into the government after they agreed to disarm and participate in UN-supervised elections. The former insurgents became the dominant party in the Parliament, but since they did not win an outright majority, they have to cooperate and negotiate with other parties. After less than a year in office, Prachanda resigned as prime minister in a dispute with other parties over control of the military. But he did so without bloodshed because the revolutionaries were enmeshed in the political process. The lesson is that entrenched ruling elites who do not serve the greater good must be driven out and the revolutionaries then brought into a democratic process.

When our group arrived in 2006, just after the king had backed down to the Katmandu demonstrators, the country was in a celebratory mood. The demonstrators and military had left the streets and the vendors, local shoppers, and tourists had returned. When we arrived in 2008, there was a growing confidence that peace had returned to Nepal. The despised king was gone, the Maoists had successfully participated in elections judged fair by neutral observers, and the Maoist fighters had laid down their arms under UN supervision.

So much history had occurred in just a few years. None of it, Niru and Ganesh told me, had any effect on Basa village. According to them, Basa had been virtually unchanged for 500 years. No electricity or running water and nothing moved on wheels around Basa. It's only experience of all the history that had roared through Katmandu in the previous decade was stories brought home by the men who worked for Niru's expedition company.

Niru and Ganesh told me that if I was able to organize a group to come to Basa, we would be only the third group of “white people” to visit Basa. The second group was French and they had supervised the building of a small addition to the school building in the spring of 2008. The first was the French-Canadian group that worked with the villagers to build the school in 2003. The idea of a trek off the tourist trails to a village with no electricity, running water, machinery, or wheels and nearly untouched by the modern world intrigued and excited me.

Most of the Sherpa villages in the Khumbu had developed electricity and water systems by 2003. I interviewed Ang Rita Sherpa, who runs a lodge in Pheriche along the Base Camp Trail, when I stayed with him on my way to Everest Base Camp during the Jubilee celebrations. He was worried about the downturn in tourism caused by the civil war and exacerbated by 9/11. I asked what he would do if his business failed. He said his family would have to return to herding yaks and growing potatoes and barley.

“Before tourism, Sherpa people very poor,” he said. “Traded with Tibetans and took crops to Namche to trade. Now we can buy things with money. I don't know if business will get better. Just wait and see. If we have to return to farming, we have land here. This is Sherpa home. Can't go anywhere else.”

But I didn't really believe that he would just return to the life of his ancestors. The power of a money-based and consumeroriented economy is too seductive. I doubted he could simply let go of it. More likely, he would fight and scrabble to find a way to hang on to the gains in creature comfort that tourism had brought to his family.

I understood Ang Rita's fear and his desire for a more comfortable life. Wouldn't I feel the same in his situation? Hadn't I spent much of my adult life striving to acquire more money and a higher level of comfort for my family?

That is exactly why I wanted to experience Basa and see a village living a way of life similar to what the Sherpas had lost. And I could give back to the village of my friends and help children for generations by improving the village school. Niru had calculated that if $5,000 could be raised for the school, all needed improvements could be made and fourth and fifth grade teachers could be hired for the school. My spirit of adventure and curiosity might be slaked by a trek to Basa and my commitment to help Nepalese villagers could be fulfilled by a fundraising project for the school. So instead of planning a climbing expedition as I had originally intended, before I left Nepal in 2007, Niru and I began to develop a plan for an October 2008 trekking expedition to Basa village and a fundraiser for the school.