Roger holds an antique toy monkey below the photograph Closet from his book Boarding House (2009). Behind, in the doorway, is his wife Lynda.

Roger holds an antique toy monkey below the photograph Closet from his book Boarding House (2009). Behind, in the doorway, is his wife Lynda.

Visiting Roger Ballen at home is like taking a walk on the dark side. The views in it and around it reveal a set of mindscapes that are often unsettling in their dreamlike quality. Is something troubling about to appear from the left side? Are the sudden flashes of dark humour a prelude to something more shocking? We are unsettled as we tour his home, as we contemplate the immaculate garden and the neat rooms. After all, Ballen’s work is identified as disturbing: he explains that this is merely the audience confronting the shadow side of their psyche.

A photographer who shoots only in black-and-white, Ballen is known for making slightly nightmarish pictures that often portray life at worst as a freak show, at best as theatre of the absurd. Born in New York, he’s been permanently in South Africa since 1982, starting out as a geologist before embarking on a career as a photographer when his third book, Platteland (1994), was published. He began by documenting the small towns of South Africa and their inhabitants in one of his earliest books, Dorps (1986), his images both social comment and disturbing psychological study. There are obvious comparisons with American photographer Diane Arbus’s photographs of the marginalised, the deviants and the freaks she found in places like seedy hotels, morgues and public parks.

Ballen chose to have his home featured in black-and-white in this book because ‘I do black-and-white photography. I thought that if somebody does a story trying to link aspects of the house, the photography, and me, it would be better that way. I’m not a master of colour.’ On his website he says that ‘black-and-white is essentially an abstract way to interpret and transform what one might refer to as reality.’

Home is a suburban Johannesburg house, designed in 1976 by award-winning 1960s architect Michael Sutton, whose clean, minimalist style is characterised by a sense of quietness, balance and peace. ‘For me this home is about stability and that’s a good thing, even an important thing, because my pictures generally deal with chaos.’ Ballen often confronts his audiences with heightened visual chaos compounded by a visceral black and white and grey palette; ‘dark’ works which, one critic remarked, bring to mind artists who, through their unsettling creations, have caused audiences to wrench open their minds and be willingly pulled along in the undertow.

Look at the screwball antics of Die Antwoord’s music video ‘I Fink u Freeky’, made with Ballen, and the series of photographic images in the book that followed. Look at the ruined inhabitants of the portraits in Platteland, which captures a ravaged world of social and economic isolation, disease, poverty and alcoholism among impoverished white communities of the platteland, what Ivor Powell has called ‘the extreme loci of human existence’. Die Antwoord’s Ninja and Yolandi, on seeing Ballen’s work for the first time in their lives, ‘saw South African art that slammed so fuckin’ hard and dark’. The collaboration that followed accidentally spawned Die Antwoord.

In Ballen’s 2014 exhibition from his series Asylum of the Birds, the trademark silver gelatin images have given way to more drawing, more collage, graffiti and sculptural elements in order to create theatrical settings with mixed media. A hybrid aesthetic for even more weirdness, more disembodied alienation and grotesque to afflict the comfortable.

The thing about Ballen’s extraordinary home, by an architect whose buildings typically display enormous sensitivity to the subtleties of ‘place making’, is that when you contemplate the roof (which is 15m high in some places), it’s ‘sort of proudly in the sky. And when you look at the sky, the mountain, or the sea, there’s a tremendous sense of peace that takes hold of you. I think if you’re able to incorporate that aesthetic into your architecture, you duplicate that sense of harmony for the people who use it. I’ve lived here for about 30 years and I feel this building enriches our lives.’

‘When I go back to the house there’s order. My wife is a very ordered, neat person. Not only is the outside pristine but inside there’s no clutter. The house isn’t full of stuff. But the places where I take my pictures are the opposite, so my photos are full of stuff. This allows me another viewpoint. I can see both sides of the mountain at one time.’

Giant delicious monsters out in the garden appear as though they’re trippy disturbing elements from one of Ballen’s own photographs.

Michael Sutton’s architecture was a highlight of the housing boom in Johannesburg in the 1960s. One of his later works, the Ballens’ Saxonwold house occupies the established garden of an earlier homestead.

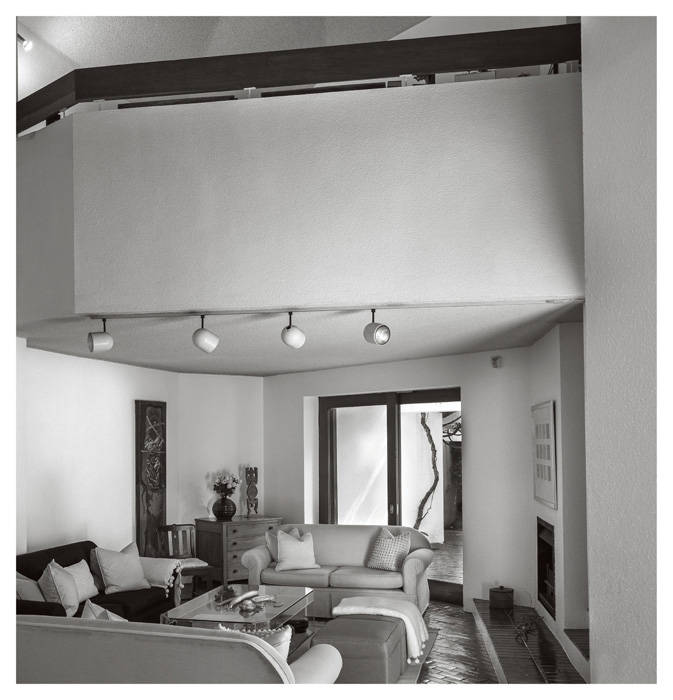

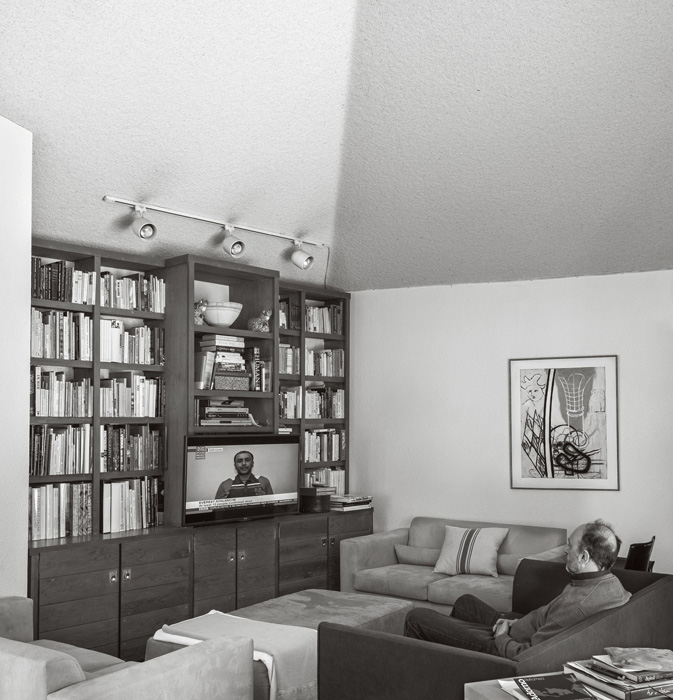

There’s a rare sense of peace in the spare, uncluttered rooms of this house. ‘It’s a place I feel very comfortable in’: (left) the living room; (right) the family room.

The structural form of the house was the appeal when Ballen considered buying the building. The entrance hall leads to the front door in the background.

The stairway to the study.

Always a master of black-and-white photography, Ballen’s own pictures are rarely without humour. Here he hangs on a wild olive tree at the bottom of the garden. Why? Why not?

The recliners are immaculately positioned on the brick paving surrounding the swimming pool. Reminders are everywhere of placement, form, the synchronous, and what it means to be out of place.

A garden designed by the landscaper Ann Sutton is another highlight of this property. Many of its trees were big when the Ballens arrived. ‘Now they’re bigger. They’re like friends.’

Every facet of this house has been well considered, right down to the overhead wooden skylights in the computer room. Practical interiors that maximise Highveld light.

Many of the ornamental and durable species in Roger’s garden are more than 30 years old. ‘Plants give a wonderful sense of time, of permanency. They give a sense of stability – which is a good thing because my pictures deal with chaos.’

For Ballen, photography has been fundamentally a psychological and existential journey. Since 1979, his work has featured in a range of books, of which Boyhood was the first and Asylum of the Birds (2014) the most recent.