England 1942–1943

To the west of Bury St Edmunds in Suffolk lay the small grass airfield of RAF Westley, which was established in 1938, with two small hangars, as home for the West Suffolk Aero Club with its Taylorcraft Model A, B and Plus C monoplanes. Those who learned to fly there included some twenty or so members of the Civil Air Guard, a voluntary scheme which offered subsidized flying training. It was too small to be taken over by RAF Volunteer Reserve, so private flying was allowed to continue until the outbreak of war.

It was reopened in 1940 as a base for the Westland Lysanders of No 268 Squadron, which was followed by No 241 Squadron in 1941. After its departure the next to arrive was 652 (AOP) Squadron in August 1942. It in turn moved to Dumfries at the end of the year but left behind two young Royal Artillery officers, Captains Denis Coyle and Ian Shield. On 31 December, they were joined by AC2s Sid Peel and Arthur Windscheffel, the first RAF ground crew to arrive. At the striking of the clock to herald the start of a new year the nucleus of 656 Squadron consisted of two officers, three Army ORs and four RAF ORs. Gunner Pete Dobson later recalled that the highlight of those first few cold and rainy days was the bacon sandwiches served in the nearby Coronation Café.

On 5 January 1943, the administrative burden was eased by the arrival of the Adjutant, Pilot Officer Arthur Eaton (later Flight Lieutenant) and on the following day the formal notice of posting was received, transferring Coyle and Shield from their parent unit, 652 Squadron and confirming that Denis Coyle was to be the Commanding Officer, in the rank of Acting Major. The critical importance of Coyle’s approach to command can scarcely be over-estimated – it was he who would set the tone of the Squadron and the standards which it would adopt. He was a young man, only twenty-five years of age. He was a regular soldier, having been commissioned into the Royal Artillery from the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich (known as The Shop) in 1937. His first posting was to 22 Field Brigade; one of the last to be horsed rather than mechanized. Following the outbreak of war he served in 2nd Field Regiment with the British Expeditionary Force in France and Belgium and after being evacuated from Dunkirk he volunteered for Air OP training. He attended No 3 Pilot Training Course at Andover in December 1940, was a founder member of 651 Squadron in August 1941 and served as a Flight Commander with 652 Squadron between April and December 1942. It may be thought that he was still a fairly inexperienced officer to take on the duties of OC, but Air OP was a nascent part of the Order of Battle, which offered opportunity to those who showed initiative and talent. There is no doubt that he was an impressive figure, being described by Frank McMath as,

‘That fairly rare person, a much loved Commanding Officer; tolerant, forbearing, even patient; he knew everyone and no one feared him, but all were proud to take his orders.’

Taylorcraft of the West Suffolk Aero Club at Westley in 1939 (Eugene Prentice via Frank Whitnall).

Fellow pilot and member of A Flight, Ted Maslen-Jones added,

‘Denis Coyle was exceptionally well-equipped for emergencies, having a cool head and an abundance of energy. He had an extraordinary ability to assess a man’s character and to work out what made him tick. He was a great innovator himself and knew when to give people their head. Quite simply, he was also a good bloke.’

The first aircraft for the new squadron had not as yet arrived. However, a DH82 Tiger Moth biplane, T6897, had been left behind by 652 and with the approval of Army Cooperation Command; this was taken over by 656, allowing the commencement of flight training. It was involved in a landing accident due to fog and had to make a forced landing in a field near Buntingford in Hertfordshire on 24 January but was soon back in service. It was joined by the first of the Squadron’s proper establishment three days later – the Auster I, LB379, which was flown in by a ferry pilot from the manufacturers at Rearsby in Leicestershire. This high-wing, single-engine, monoplane type was a development of the Taylorcraft. The Mark I would soon be replaced by a slighter better version, the Auster III.

Westley had its rural charms but there was no Sergeants’ Mess, canteen or NAAFI; the officers were accommodated in Westley Hall, while most of the men had been found billets in private houses scattered around the district. A night out at the Athenaeum in Bury St Edmunds was a welcome diversion, as was an ENSA concert starring the celebrated jazz trumpeter and bandleader, Nat Gonella. By the end of the first month Denis Coyle was able to write in the Operational Record (OR) Book, describing how his command was evolving,

‘Personnel posted in :- Army 76, RAF 58. [Out of a total complement of 196 men] About 50 per cent of the authorized RAF equipment has been received, but very little army equipment. No transport has been received in spite of action taken to secure vehicles from Eastern Command. Lack of transport proved a serious handicap both to training and administration.’

The division of administrative responsibility between the RAF and the Army was always to provide something of a headache as it seemed to generate twice the amount of paperwork. The first job was, however, to start to turn the Squadron into a potential fighting unit. Its establishment comprised four flights, HQ, A, B and C. The Officer Commanding, his 2i/c and the five pilots in each flight were all Royal Artillery officers; the Adjutant, Equipment Officer and Administration Officer were RAF. To the gunner NCOs and ORs fell the duties of motor transport maintenance, driving and communications, while the RAF’s aircraftsmen maintained the Austers. The basic unit within a flight was the section, of which there were four, each commanded by the pilot, who would normally be a captain. Each section consisted of two RAF ORs, an engine fitter and an airframe rigger and two RA, a signaller and a driver-batman. Each section had a jeep and a three-ton truck and therefore could be very flexible and entirely self-supporting in the field. Communication within the section, flight and squadron (and also with other ground units) was maintained by the standard Army Wireless Set No 22, which was bulky, heavy and notoriously temperamental. For such a small unit the establishment was to prove remarkably suited to the harsh environment of Burma, when the Squadron would find itself spread over hundreds of miles, with atrociously poor lines of communication. Even the Set No 22 would perform well beyond its design specifications. By the end of February, eight more aircraft had arrived, four Auster Is and four Auster IIIs, as well as seven additional pilots, the Squadron Engineering Officer, Flight Sergeant McCarthy (later Warrant Officer) and an assortment of vehicles – three-ton trucks, motorcycles, jeeps, wireless trucks, an office lorry and the OC’s car. An unfortunate accident occurred when AC2 Windscheffel was hit on the hand during prop-swinging and was admitted to hospital at Ipswich where, after surgery, he recovered the use of his hand and rejoined the Squadron in due course. Training began in earnest in March when B Flight was sent to take part in Exercise Spartan. Frank McMath, of A Flight, recalled a lesson learned at that time which he later put in to practice in Burma,

‘Diving low over the heads of the marching troops with engine throttled right back so as to reduce the noise, I pointed in the direction of the airfield and shouted out of the window “Turn left here”, and then was relieved to see them set off the right way. I had learnt this shouting trick years ago from the OC when, as a very new officer, I had led the Squadron HQ convoy to an exercise in Norfolk. Halting a few miles from the destination in the hope that a driver, whom I had lost, would catch up before we turned off the main road, I was a bit disconcerted to see the OC fly over very low and shout “Get a move on” – in very clear and angry tones.’

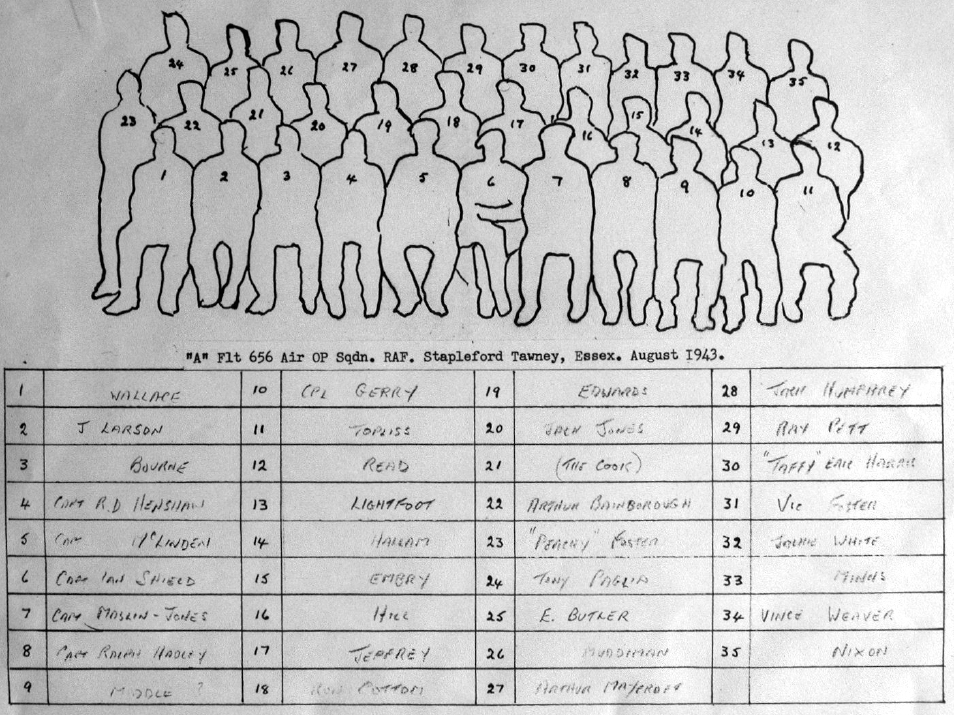

Names to go with the above photograph.

It had been decided that the ever expanding Squadron’s needs would be better met by moving from Westley to a larger RAF airfield, Stapleford Tawney, near Romford in Essex. Stapleford opened in 1933 as an operating base for Hillman’s Airways – a charter company formed three years earlier by businessman Edward Hillman. In April 1933 he started a scheduled service to Paris, France, using his newly acquired DH 89 Dragon Rapides at a return fare was £5.10s.0d. Stapleford was known in those days as Essex Aerodrome. Sadly, Hillman died at a relatively early age in 1934 and this far-sighted and enterprising pioneer of British civil aviation is now all but forgotten. The airfield was requisitioned shortly after the start of World War II as RAF Stapleford Tawney. A long perimeter track and dispersal points were built and some accommodation buildings were erected. By the end of March 1940 the airfield was ready to become a satellite station for North Weald. In March 1943, Stapleford was transferred from Fighter Command and placed within No 34 Wing, Army Cooperation Command. As for Westley, it welcomed two more Air OP squadrons before the end of the war; 657 Squadron for eight weeks from May 1943 and in February 1944, 662 Squadron began a stay of four and a half months.

Corporals Derrick Beard and Alfred Howard were the first RAF personnel to join the Squadron at Bury St Edmunds, having spent two weeks at the Taylorcraft factory in Leicester where they, ‘had to work on the construction of the aircraft from start to finish,’ this in-depth knowledge would prove of considerable assistance in the months ahead.

By the middle of March the Squadron had relocated successfully and a further seven pilots had arrived, shortly to be followed by a batch of sixteen new Auster IIIs replacing the original aircraft (though the Tiger Moth was also retained). It was now possible to establish the regular three flights, A, B and C and to embark upon a series of training exercises with a variety of army units around the country. This would often require the flights to operate detachments away from Stapleford and independently of SHQ.

Ted Maslen-Jones, also of A Flight, remembers live shooting in support of artillery regiments in Wales and the North Country and particularly valued a special permit,

‘During this period I carried with me in the aircraft a form of authority allowing me to carry out low flying and to land virtually anywhere in the country. This was a tremendously valuable privilege in terms of gaining experience and developing these essential skills, which would stand us in such good stead later and we were encouraged to make full use of it, particularly on journeys to and from exercises. The opportunity to make short landings in unfamiliar places was really useful. Manoeuvrability at low-level was really our only defence against enemy fighters, at the same time helping us to avoid detection from the ground as well as in the air. We carried no armaments and no parachute. When in trouble there would be no alternative to forced landing. In such a situation the relatively slow speed of the Auster was a great advantage.’

He enjoyed certain other aspects of Exercise Border, which took place in June 1943, on the artillery ranges at Otterburn in Northumberland, recalling,

‘I operated with my section from a landing ground that was normally a field full of sheep and was adjacent to the Percy Arms. This was most convenient and gave rise to several enjoyable evenings after flying had finished.’

Some idea of the intensity of the preparation may be gathered from the fact that – to take a not untypical day – on 1 June, the Squadron was spread around half a dozen different locations; SHQ and one section of C Flight were at Stapleford Tawney; A Flight was at Bramford in Suffolk; B Flight at Redesdale in Northumberland, attached to the Guards Armoured Division; while the three remaining sections of C Flight were detached to 145th Field Regiment, 120th Field Regiment and 61st Recce Regiment. SHQ also practised deployment, while training took place in night flying, map-reading (not only for pilots but also for the drivers, commencing with expeditions by bicycle, a section at a time), cross-country flying, short field landings at advanced landing grounds (ALGs), testing the radios and microphones and on 25 June, weapon drill and the firing of rifles, Bren Gun, Sten gun and Tommy guns. On 19 June, Major Coyle had made what must have been a very useful visit to Old Sarum for a Squadron Commanders’ Conference, which was addressed by Major ‘Jim’ Neathercoat, the OC of 651 Squadron, on the experiences of 651 and 654 Squadrons in Tunisia. Ten days later the Squadron received its Mobilization Order from the War Office – it was to be ready to deploy to a tropical theatre by 1 August. In July, all personnel were inoculated and vaccinated and took it in turn to have a fortnight’s embarkation leave. Much effort was devoted to packing, as the C Flight diary noted,

‘Inter-flight rivalries develop as packing continues! A Flight pride themselves on their speed, but C Flight prefers the security of the finished product. B Flight made a corner in wood wool [packaging material made from slivers of wood], which would have put maintenance out of business if we hadn’t gone to their aid with all available reserves. C Flight stopped work at 1945 hours, just in time for the ENSA show.’

Many years later, the prevailing mood within the Squadron at that time was described by Bombardier Ernest Smith,

‘We were about half-and-half Royal Air Force and Royal Artillery and we got on together wonderfully – a bit of banter, naturally, about Brylcreem Boys and Brown Jobs – but we lived together, messed together and went out on the town together. The officers, with the exception of the Adjutant and the Equipment Officer, who were RAF, were all Royal Artillery and young. The whole outfit was informal, cheerful and matey.’

Towards the end of July the issue of tropical kit started, this included pith helmets or solar topees. Few were impressed by these relics of earlier Imperial times, indeed Ted Maslen-Jones recalled that, some weeks later, he and several others threw them overboard into the waters of Bombay Harbour and watching a ‘strange-looking flotilla’ bobbing away.

Denis Coyle later summed up the first few months of the Squadron’s life as follows,

‘The formation of 656 Air OP Squadron RAF went very much the same way as for all the other squadrons in this era. It was a matter of collect ing together pilots, aircraft, soldiers, airmen and vehicles and turning them into a flying and fighting unit. One had the impression that the soldiers and airmen were a trifle suspicious of each other until they found that they were both exactly the same without their uniform on and although the airmen were essentially the technicians looking after the aircraft and the soldiers were the drivers and signallers, many firm friendships quickly developed. By mid-August, after some fairly intensive training, we were warned for an unknown tropical destination and spent the last month in collecting all the aircraft spares that we could possibly lay our hands on and packing them up as securely as possible in thousands of packing cases. Included amongst the packing cases but in very specially constructed containers were the instruments of our dance band which had been formed earlier on and which had already earned a lot of money for PRI by playing in the local village halls near Stapleford Tawney in Essex where we had been based.’

Before saying farewell to Stapleford Tawney a cocktail party was held in the Officers’ Mess, as well as parties in the Corporals’ Club and Sergeants’ Mess and an Airmen’s dance with free beer provided by the Station and the Squadron.