UK and Rhodesia 1978–1981

On Thursday, 23 March 1978, a Change of Title Parade was held at Jersey Brow, Royal Aircraft Establishment, Farnborough. 664 Squadron AAC, which was under the command of Major Chris Pickup, became 656 Squadron AAC. Farnborough, of course, is one of the cradles of British aviation and had played host to the Army’s airmen since the nineteenth century when the Royal Engineers had first flown their ‘war balloons.’ 664 Squadron had been formed originally in December 1944, as one of three Canadian Air OP units which served in north-west Europe in 1945. 664 Squadron’s immediate antecedent was 21 Reconnaissance Flight, which had been based at Farnborough since 1965, and became an Interim Aviation Squadron in 1968, and then 664 Aviation Squadron in 1969. In 1973, ‘Parachute’ had been incorporated into the Squadron title, as most of the aircrew and LAD were trained parachutists, and everyone wore the Red Beret. With the disbandment of the Parachute Brigade on 1 April 1977, these entitlements were withdrawn. As the 2i/c, Tony McMahon noted,

‘In March 1977 the squadron exchanged its red berets for the AAC berets on a small parade outside the squadron hangar, with many a tear shed by those who held the para association dear. In fact, there was one REME SNCO who took it so badly that he avoided wearing blue beret whenever he could. I ignored his protest and eventually he came round.’

The Squadron’s primary function in 1978 was the support of 6 Field Force and it consisted of two flights; A Flight with six Gazelles (replacing Sioux from 1 April) and B Flight with six Scouts. The SQMS, Ross Skingley, remembers,

‘The Squadron hangar and offices were situated close to the centre of this large MOD specialist airfield for aircraft and systems testing. There was plenty of room, as the hangar had been designed to accommodate VC10s. During the annual air displays we had a grandstand seat, though it was a little close for comfort should there be a major accident.’

The Squadron was kept very busy during the year, with two Scouts being detached to The Gambia between February and May for exercise with the Royal Anglian Regiment, two Gazelles spending April in Germany, again on exercise, a visit to Canada for B Flight in September to BATUS (the British Army Training Unit Suffield) and between October and November, participation in a main field training exercise in Denmark. Tony McMahon has fond memories of the trip to Denmark,

‘Exercise Arrow Express proved to be an amazing experience. We self-deployed by air to Denmark, the support elements going by sea. Miraculously we married up over there and proceeded to support the Brigade HQ. As second in command my job was to find a squadron location. I happened upon a wonderful estate and negotiated our occupation with the owner, Ole Molgard Christensen. He made us very welcome, treating the officers to his store of Glenlivet on the first evening and then declared that he would have a dinner party in our honour. He expected that we would have deployed with full mess kit and was very disappointed to discover that we barely had a tie between us. At the end of the exercise he challenged us to a football (soccer) match and our boys were slightly nonplussed to discover that half their local team were girls who were not shy when it came to sharing the same changing room. Nobody remembers the result of the game. Our Danish host subsequently became an honorary member of the Squadron.’

England 1978–2012.

The pattern continued into 1979 with two Scout crews being deployed to Belize between January and April. The colony formerly known as British Honduras was being threatened by its larger neighbour, Guatemala, and a strong British military presence was being maintained to deter any aggressive moves (Belize attained full independence on 21 September 1981). Two Scouts and eleven personnel were attached to 660 Squadron in Hong Kong from July to October, as reinforcements in the prevention of illegal immigrants. According to Sergeant Dick Kalinski, the job consisted mostly of, ‘Hovering over the Mai Po marshes while the crewman in the back lent out and pulled them in.’ As well as these operational deployments, aircraft were also sent to take part in exercises in Italy, Germany, Denmark, Kenya and the USA. Tony McMahon also recalls receiving some assistance,

‘Whilst at the Staff College, Camberley, at the beginning of 1979, I called upon 656 Squadron to provide a static display of Scouts with SS.11 missiles and the new Gazelle during the aviation study phase and it impressed even the Commandant, Major General Frank Kitson, if only for the noise they made on arrival!’

Chris Pickup has happy memories of his period in command,

‘I seem to recall that within a week, during February 1979, I flew over the sea ice around Copenhagen and the primary jungle of Belize. I also took a Gazelle to Italy for a week in the summer of 1978, to fly the Brigade Commander when he went out to recce one of our NATO reinforcement options on the Tagliatmento River. And we were always flying him to Caen to visit Pegasus Bridge. We also forged a link with Bulmer’s Cider in Hereford – this through the Chairman, Peter Prior, who set up the Military/Industrial Exchange Scheme. Peter was a free-fall enthusiast – in fact I think he held the world altitude record at one time – hence his interest in what had been the Parachute Brigade. Anyway, he entertained the whole Squadron for a weekend at Bulmer’s, to include not only a factory visit, but also; a trip in their steam train, a service in the Cathedral and a very smart dinner. As was the case in Denmark [referred to above], at Hovdingsgaard, when the owner invited the whole Squadron to lunch, everyone conducted themselves in an exemplary fashion. I was amazed and really rather proud of them!’

Rhodesia 1979–1980.

The Squadron also had to maintain a capability to be ready to support the civil power in the UK should an incident arise, eg. a natural disaster or a strike involving essential services. In May, Chris Pickup was succeeded in command by Major Stephen Nathan.

Rhodesia

On 15 November 1979, the Squadron was given five weeks’ notice to be ready to depart for Rhodesia, where elections were to be held which it was hoped would bring to an end a dispute which had begun on 11 November 1965, when the government of the British colony of Southern Rhodesia, under its Prime Minister, Ian Smith, issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence (UDI). Attempts to reach a compromise by personal meetings, held first on board the cruiser HMS Tiger and then the assault ship HMS Fearless, between the British Prime Minister, Harold Wilson and Ian Smith failed to reach an agreement. Trade sanctions were imposed and a naval blockade was implemented. Rhodesia was declared a republic in March 1970. Then, in 1972, a guerrilla campaign was begun with scattered attacks on isolated white-owned farms by the military wings of the Zimbabwe African National Union (ZANU) and the Zimbabwe African People’s Union (ZAPU), led by Robert Mugabe and Joshua Nkomo respectively, which wished to bring white rule of the country to an end. Mugabe’s army was ZANLA (Zimbabwe National Liberation Army) which was largely drawn from the Mashona tribe and received considerable support from China, while Nkomo’s was ZIPRA (Zimbabwe People’s Revolutionary Army), which was mostly Matabele and obtained weapons and training from Cuba and the USSR. Both peoples were traditionally enemies. Initially, the activities of ZANLA and ZIPRA were contained by the Rhodesian Security Forces (RSF), but it developed into a very nasty conflict with bloody deeds on both sides. However, the situation changed dramatically after the end of Portuguese colonial rule in Mozambique in 1975. Rhodesia now found itself almost entirely surrounded by hostile states, and even South Africa, its only real ally, pressed for a settlement. All attempts made by Smith, Nkomo and Mugabe to broker an honourable peace that would guarantee the rights of the white minority failed. In September 1976, Smith accepted the principle of black majority rule within two years. By 1978–79, the ‘Bush War’ had become a contest between the guerrilla warfare placing ever increasing pressure on the Rhodesian government and civil population, and the Rhodesian Government’s strategy of trying to hold off the militants until external recognition for a compromise political settlement with moderate black leaders could be secured. As the result of an internal settlement between the Rhodesian government and three moderate African leaders, who were not in exile and not involved in the war, elections were held in April 1979. The United African National Council party won a majority in this election, and its leader, Abel Muzorewa, a United Methodist Church bishop, became the country’s Prime Minister on 1 June 1979. The country’s name was changed to Zimbabwe Rhodesia. While the 1979 election was non-racial and democratic, it did not include ZANU and ZAPU. In spite of offers from Ian Smith, the latter parties declined to participate. Bishop Muzorewa’s government did not receive international recognition. The Bush War continued unabated and sanctions were not lifted. The international community refused to accept the validity of any agreement which did not incorporate ZANU and ZAPU. The British Government (then led by the recently elected Margaret Thatcher) issued invitations to all parties to attend a peace conference at Lancaster House. These negotiations took place in London in late 1979. The three month long conference almost failed to reach conclusion, due to disagreements on land reform, but resulted in the Lancaster House Agreement. UDI ended, and Rhodesia reverted to the status of a British colony under a new Governor, Lord Christopher Soames. Some 1500 British and Commonwealth troops (drawn from Australia, New Zealand, Fiji and Kenya) were sent to monitor and supervise the ceasefire between the Rhodesian Security Forces (RSF) and the guerrillas – known collectively as the Popular Front (PF) – with the prospect of an internationally supervized general election in early 1980. This was named Operation Agila and the collective name of the troops deployed was the Commonwealth Monitoring Group (CMG).

Before deploying, the Squadron used its five weeks of grace (while fourteen deployment timetables were considered and rewritten) to study the military and political background; to brief themselves on the climate and terrain; to discuss the technical problems associated with hot and high operations; to study detailed maps, preparing the aircraft; painting them white (which washed off in heavy rain); covering them with DAYGLO (and removing it again) and finally, adding large white crosses to fuselages and tail fin, then collecting special stores; armour (which in the event was not used); infrared shields (which were); survival packs, sand filters and SARBE beacons. Ross Skingley comments on the provision of armour,

‘The full set of engine and cockpit armour was fitted, but on the test flight the QFI found that it would be too heavy to operate at 6000 feet plus (the altitude at Salisbury airfield) with fuel and four passengers on board. Therefore the only amour was a pan in the seat for protection of rear ends and other essential body parts!’

The initial requirement had been for a detachment of three Gazelles, which were placed on forty-eight hours’ notice, with a further detachment at seventy-two hours’ notice. Within three days of arriving in theatre it was accepted that another six Scouts should also be sent out (which the Squadron had known all along would be required).

The first elements of the Squadron (and also No 230 Squadron RAF) left Brize Norton on 20 and 21 December 1979, in RAF VC10s and C-130 Hercules, as well as enormous USAF Starlifters and Galaxys, routing via a combination of Cyprus, Egypt and Kenya. It was noted that a single Galaxy could transport three Gazelles, three Pumas and 20,000lbs of freight and still have room for forty passengers. Ross Skingley, who was by this time SSM, recalls,

‘After about twenty hours, including a suck of fuel in Cairo, we came overhead Salisbury International at night; however, because of the threat of SAM 7s, the C-5 spiralled down from about 30,000 feet and as there were only about four small windows in the boom, where we were sitting … it was interesting!’

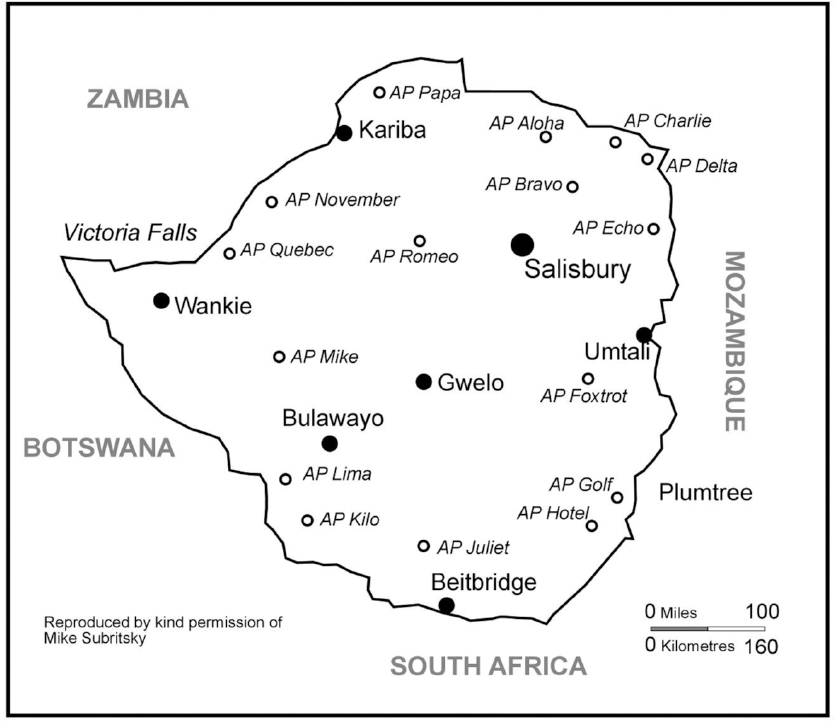

Within two weeks all eighty personnel, six Scouts and six Gazelles had arrived, under the command of Major Stephen Nathan. Maintenance was the responsibility of a detachment from 70 Aircraft Workshop. The Gazelles were based in the capital, Salisbury, with the HQ Monitoring Force and Government House, sharing a hangar with the RAF as well as Rhodesian Bell UH-1Ds and Alouette IIIs (remarkably and somewhat worryingly, all the Rhodesian helicopters had twin waist guns which were left unguarded, loaded with ammunition and belt feeds); while the Scouts were in Gwelo, at the Rhodesian Air Force base, Thornhill. The Gazelle crews covered the north and east of the country, which was twice the size of the UK, while the Scouts looked after the west and south, which was the location of many of the assembly points for ZANLA and ZIPRA guerrillas coming in from the bush. Operations began on Christmas Day, with two aircraft being tasked to fly Brigadier John Learmont, the Deputy Force Commander and some of his staff to Umtali. Brigade HQ was situated in the Morgan High School, Salisbury, which possessed playing fields in which helicopters could land. Many years later General Sir John Learmont wrote,

‘Stephen Nathan received all his tasking from the Air Cell in the HQ and I saw him almost on a daily basis. Having such close helicopter access to my HQ was a considerable advantage from my point of view.’

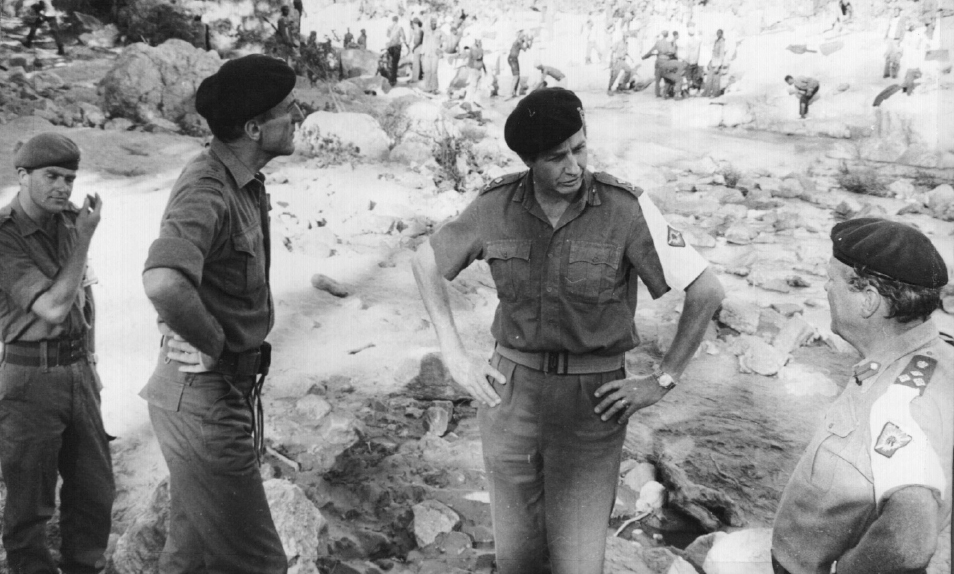

Major Tim Purdon, Lieutenant Colonel Ian Hurley, former 656 Squadron pilot, Major General Ken Perkins and Brigadier John Learmont discuss matters in Rhodesia, 1979.

Tragedy soon struck the RAF, as on 27 December, a Puma crashed after hitting low wires near Salisbury, killing Flight Lieutenant M. Smith and Master Air Loadmaster M.R. Hodges of 230 Squadron and Flying Officer A. Cook of 33 Squadron. The optimum operating height was debated, the Squadron decided to fly at above 2500 feet unless forced down lower by the weather. This initial period was a very tense time; the weather was atrocious as it was the wet season, and moreover, no one knew how the guerrillas would react and if self-defensive force would have to be applied. The ceasefire came into effect at 0001 hours on 29 December. Some thirty-nine Rendezvous Points (RV) and sixteen Assembly Places (AP) were set up across the country. During a ceasefire period of seven days, members of ZIPRA and ZANLA were guaranteed unhindered movement through the RVs and into the APs. Here their names were recorded, together with details of the weapons they carried. They were also provided with food, clothing and bedding. Considerably more people arrived than had been expected, some 22,000. The heavily-armed and ill-disciplined fighters, tended to carry their weapons loaded, cocked and with safety catches off, which did nothing to simplify the operation. The scale of the task created something of a logistical nightmare, which the AAC and RAF helicopters did their best to alleviate with many resupply missions. The OC later commented,

‘The guerrillas were never entirely relaxed when we were in the air; at all locations they covered our approach with at least one AA machine gun and, whilst the aircraft were on the ground, with small arms and RPG-7… in the first few days we gave away hundreds of cigarettes… and showed many of them around the helicopters in order to create some kind of trust. What else can you do when armed with a 9mm pistol and a white flying helmet, surrounded by hundreds of rifles and rockets?’

On one flight the OC had to carry a PF officer who had been injured while out hunting buffalo, one of the most dangerous of animals. He had been badly gored and had ‘a huge hole in his leg and I had blood all over the cabin.’

The CMG’s role was to monitor the activities of the PF and the RSF and report any violations of the ceasefire – it had no powers to intervene in the event of a recurrence of hostilities, nor indeed was it equipped to do so. During the first month of the deployment, the Squadron’s twelve aircraft flew 1000 hours in the hot and high local conditions which varied from 1500 to 8000 feet above mean sea level – REME, as ever, worked wonders and ten helicopters were always available for duty. The chief problem areas for the Squadron as a whole concerned the availability of adequate refuelling facilities and of suitable accommodation, the need for better radio sets and of extra means of land transport. It was noticed that the pilots’ navigational and map-reading skills improved,

‘Some of our better routes were over 100nm of absolutely flat bush with no navigational features at all. You just had to rely on the compass and the clock and then amaze yourself when, at the given time, your destination suddenly appeared.’

Although, by African standards, Rhodesia had a well-developed network of road and rail links, in reality there were thousands of square miles of featureless flat bush to traverse. Off the main tarmac roads transport was restricted to bush tracks which, at the time of the deployment, were considered as a potential landmine hazard. Air support was therefore absolutely crucial to the CMG’s mission. The guerrillas were well-armed and before deployment the potential threat had been assessed as quite considerable.

On 5 January 1980, a patrol of two Land Rovers collected about ten guerrillas and was transporting them along a dirt road at the bottom of the Zambezi Escarpment when the first vehicle hit a landmine, seriously injuring the driver and wounding others, including the guerrilla commander. He had been standing up in the back of the first Land Rover, holding on to the roll bar and posing when the explosion occurred and was blasted over the bonnet, landing in a heap on the road, minus his clothes. Staff Sergeant Chris Griffin in a Gazelle and Captain Sam Drennan in a Scout, with a medic each, were scrambled to attend this incident. On arrival they landed beside the road, the situation was tense, but well managed by the three unwounded British ground troops. The driver was in a bad way, with serious injuries to his leg. This was expertly dealt with by the Rhodesian combat medic who had accompanied Drennan, he splinted the leg using a rifle and had the casualty prepared for shipment quickly. The British medic was dealing with the injured guerrilla leader whilst the remaining guerrillas were increasingly panic stricken as their leader was barely conscious and no one else could make decisions. Drennan decided to send Griffin off to hospital with the injured driver; he would then take the guerrilla leader when he could be moved. The remaining guerrillas refused to let the Gazelle go and made their point with wild eyes, shouting and waving of weapons. This situation lasted for a while and the patrol commander communicated their predicament to HQ in Salisbury, who, after an hour or so, produced a ZANU leader (Comrade John) to speak to his men on the HF radio. This resulted in the Gazelle being released, but the Scout had to stay. When invited to help carry the injured driver to the Gazelle, the guerrillas refused, as they had been responsible for planting the landmine and also had put some close to the road, but did not know where they were. The driver was carried to the Gazelle, using the footprints made by the crew on arrival. No explosion occurred and the Gazelle departed. The guerrilla leader’s condition continued to deteriorate and his comrades continued to panic. After protracted conversations with Comrade John in Salisbury, the guerrillas eventually agreed to let their leader be taken to hospital. One of the main problems during the long conversations was that the guerrilla doing the talking could not understand that the transmit switch had to be pressed whilst he was talking, which resulted in repeated attempts to communicate. It would have been comical if it hadn’t been so unpredictable. Drennan insisted that the guerrillas carry their leader to his aircraft and stood well back in case they rediscovered one of their land mines. This saga lasted for about three hours and had to be resolved by peaceful negotiation as the alternative was to wreck the ceasefire. Sam Drennan recalls another incident which could have worked out badly,

‘WO2 Mick Sharp, Colour Sergeant Sean Bonner and I arrived at a refuelling point near a football pitch in SW Rhodesia. One of the British ceasefire monitors (a Lieutenant Colonel) had been tasked with defusing a volatile situation where a group of armed ZIPRA guerrillas had assembled at one end of the football pitch, whilst a group of Rhodesian troops at the opposite end of the pitch were about to dispense summary justice. His plan was to get between them and either prevent bloodshed or get a posthumous medal. Sharp and I conferred and decided that Bonner was the best man for the job and ideally suited for the said medal! He landed the monitoring officer on the centre spot and both sides were so astonished that the situation was controlled.’

In the event there was only one confirmed case of a helicopter being fired at from the ground, this was on 25 February and no damage was sustained. The daily flying task included the movement of men and stores, liaison sorties, casevac, delivery of mail, newspapers and medical supplies, a flying doctor service and the pay office run. A ‘milk-run’ service was instituted serving each location across the country, which guaranteed (weather permitting) a visit by a Scout or Gazelle every forty-eight hours. The Scout was by this time a much-loved and proven workhorse; however, the Squadron noted with considerable satisfaction that the Gazelle was really good too. Ross Skingley recalled,

‘My main role as SSM was to fly with the daily mail delivery Gazelle to Assembly Areas to hand out and collect mail going out from the few Brit Troops who were controlling these sites. Usual delivery times were seven to eight hours a day visiting two to three assembly areas. There were a few tense times with firefights, the odd planted explosive device and in one instance I had a stand-off between a fully armed ZANLA guerrilla and RSF soldiers, who were about to shoot the guerrilla (their arch enemy), who had been wrongly brought into our hangar at Salisbury by one of our British monitoring force liaison officers.’

During its time in the country the Squadron flew 1000 sorties in 2200 flying hours, carried 2000 passengers and 100,000lbs of freight (incidentally finding out that a Gazelle could carry a load of twenty-five empty jerry cans) and covering 250,000 miles (the RAF’s Hercules delivered no less than 1,000,000lbs of stores during the first thirty days – the biggest such operation since the Berlin Airlift). The Squadron was also tasked to fly to Mozambique and Zambia and ‘bent a Gazelle doing engine-off landings.’ Towards the middle of February tension increased once more and many sorties were flown to the APs to enhance the stocks of arms and ammunition stored in the armouries – just in case the situation turned nasty and CMG troops had to fight their way out. No doubt it felt a little similar to Rourke’s Drift. Thankfully, the worst case scenario did not happen and in the last week of the month the Squadron flew members of the Ceasefire Commission, which included Major General Sir John Acland, the CMG Commander, as well as senior officers of both the PF and the RSF, around all the APs. Within a week a training camp had been set up for ZIPRA forces, where British officers and SNCOs began to work with them. A similar camp was planned for ZANLA, while Rhodesia police and soldiers began to take over the administration of the APs. It seemed to a relieved Major Nathan like a minor miracle and just in time in the light of the election results which would, ‘shake the whole establishment to its foundations.’ The election results were announced on 4 March. ZANU (PF) led by Robert Mugabe won this election, some alleged, by terrorizing those who opposed ZANU, including supporters of ZAPU. The observers and Lord Soames were accused of looking the other way, and Mugabe’s victory was certified. Nevertheless, few could doubt that Mugabe’s support within his majority Shona tribal group was extremely strong. It is believed that elements in the Rhodesian armed forces toyed with the idea of mounting a coup against a perceived stolen election, to prevent ZANU taking over the government, but this was never realized. On 18 April 1980, the country gained independence as the Republic of Zimbabwe, the Union Flag was lowered for the last time from Government House and the capital, Salisbury, was renamed Harare two years later. Almost as soon as the Monitoring Force had departed Mugabe began to settle old scores, firstly against supporters of Joshua Nkomo in Matabeleland and then eventually against the white farmers, with the unhappy results stretching into the twenty-first century.

Major Stephen Nathan and Brigadier John Learmont with a 656 Squadron Gazelle in Rhodesia.

However, for the Squadron, its involvement had come to an end on 10 March, when the first return flights commenced, with everyone being back in the UK by 19 March. Brigadier Learmont wrote a letter of appreciation to the OC,

‘In the early days you and your pilots were literally the lifeline for the soldiers at the RV points … it was a magnificent performance and will never be forgotten by those whom you supported … As one of your more regular passengers, I would like to record that it is a privilege to have been flown by 656 Squadron.’

In an e-mail to the author, Sir John added,

‘I am not sure if my final letter to Stephen did full justice to the Squadron. I can reiterate now that to a man they were magnificent and I have no doubt that but for their heroic performance Op Agila would have failed.’

Back in the UK

Major W.J.H. (Johnny) Moss, ‘a forthright officer who managed with style, not forgetting the social side of life,’ assumed command in June 1981 and in July, Sergeant Dick Kalinski took part in Airborne Forces Day which was also the 656 Open Day. On that day he had completed 999 parachute jumps and also 999.8 flying hours. He took off from Farnborough with a parachute on his back and the Squadron QHI in the left-hand seat. At 999.9 flying hours and at an altitude of 3500 feet, he said, ‘You have control.’ As the 1000 hour figure was reached he jumped out, thus accomplishing a remarkable double.

Airtrooper Tim Lynch joined the Squadron in 1981 straight from training at Middle Wallop and has happy memories of a ‘fairly relaxed regime’. He recalls one of his regular duties,

‘As a signaller, I spent a lot of time on exercise away from the main Squadron sitting on hilltops with an FFR (Fitted For Radio) Landrover rebroadcasting messages to and from the aircraft. Generally it meant a relatively relaxing time enjoying the view but also brought me into contact with the bane of my existence – Don 10 telephone cable. We laid the stuff for miles and then went out and wound it all back in again – perching on the bonnet of the Landrover and frantically winding a reel to collect it all up. In between, we went out to fix the never ending breaks in it.’

He also enjoyed joining the gliding club at Farnborough, a parachuting course organized by Dick Kalinski and exercise deployments to Denmark, Kenya and Schleswig-Holstein, where the RSM at the German Panzer unit which hosted them was very hospitable even to the extent of supplying his guests with homemade cakes. Johnny Moss remembered the NATO exercise Amber Express in Denmark for the following reason,

‘The Squadron was based for two days at a Schloss owned by a charming Dane called Ole Christensen. He knew 656 from previous encounters and when the exercise was over, he invited us all back to a party laid on in our honour. To our amazement a coach load of young ladies arrived from Copenhagen in what can only be described as “Night Club attire”. Everyone was somewhat shell-shocked by this display of hospitality and, whether it was safety in numbers or exercise fatigue, I shall never know, but absolutely nothing happened. The boys all stood at one end of the Great Hall, with stags heads peering down on them drinking beer, while the girls stayed at the other end, giggling. Call it a missed opportunity!’