To describe Paul Poiret as a fashion designer may be to do him an injustice. Consider the achievements of the year 1911, his annus mirabilis, when he created the Rosine house of perfume, the Martine school of decorative arts (with accompanying shop), the Colin paper and packaging workshop, and a fabric printing factory in collaboration with the artist Raoul Dufy. That same year also saw his publication of Les choses de Paul Poiret vues par Georges Lepape, a book of exquisite fashion drawings that did much to fuel the revival of fashion illustration. All this, combined with his achievements as a couturier, made Paul Poiret a central figure in the artistic and creative development of Paris in the early twentieth century. In the 1910s, he was known in America as the King of Fashion, while in Paris he was Le Magnifique. To cap it all, he was also an outstanding cook.

As a couturier, his list of accomplishments was spectacular, led by his championing of a revival of the neoclassical style of 1790s France—high-waisted flowing clothes that followed the fluid, natural lines of the body. This revival swept away in a few short years most of the nineteenth-century styles that squeezed, exaggerated or disguised the body. Paradoxically, Poiret was also responsible for the hobble skirt, cut so tight that the wearer could barely walk, an innovation that aroused ridicule while fuelling the oxygen of publicity for the designer. More positively, his enthusiasm for Orientalism, drawing on influences from India to China and Japan, infused fashion and interior design with a burst of strong, dynamic colours, even before the Ballets Russes and Bakst had reached Paris. He paved the way for the style known as Art Deco, making a spectacular contribution both in terms of fashion and interior decoration to the Exposition des Arts Décoratifs in 1925, the event that gave the movement its name.

Poiret was a true Parisian, born in 1879 near Les Halles, to parents who owned a wool cloth shop. As a young child, he was an avid art gallery visitor, entranced by colours in particular. He was also a lover of the theatre, sketching the costumes of the actresses at the Comédie-Française. Forced by his father to become an apprentice to an umbrella maker, he preferred to spend every spare moment developing his sketching abilities. The breakthrough came in 1898 when the couturier Jacques Doucet offered him a job as a junior assistant. His first piece, a red wool cape, received orders from 400 customers. Poiret went on to design for two star actresses of the period, Gabrielle Réjane and Sarah Bernhardt, but was sacked by Doucet after a falling-out with Bernhardt. Following a brief and unhappy period of military service, he went to work at the house of Worth, where he created a coat cut like a kimono that famously upset its potential client, Russian Princess Bariatinsky, but was a precursor of his Orientalist style. Once again, however, he lost his job.

In 1903, with money from his mother, he opened his own house at 5 rue Auber. Encouraged by the magnanimous Jacques Doucet and championed by the actress Gabrielle Réjane, Poiret swiftly began to make waves. His muse was Denise, the daughter of a Normandy textile manufacturer. They were married in 1905. In those early days as a couturier, his enemy was the corset. As he put it himself, ‘It was in the name of Liberty that I brought about my first revolution, by deliberately laying siege to the corset.’

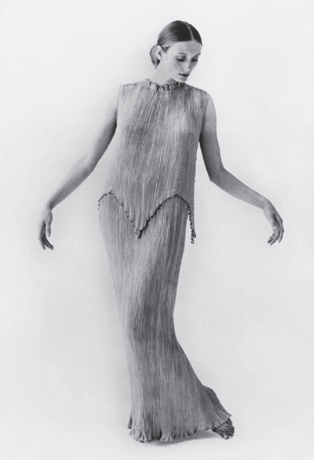

Poiret always designed on live models, working from the shoulders, initially creating a series of surprisingly plain gowns that skimmed the outlines of the figure. By 1906, he had banished the corset, replaced by the girdle and the brassiere, which he can lay claim to have invented. Among the other designers of the period who also dropped the corset were Lucile and Madeleine Vionnet, but Poiret, a brilliant self-publicist, stole most of the credit. Unlike Vionnet, he tended to work on the straight grain rather than on the bias. As Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute curators Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton point out, the new natural silhouette marked a fundamental shift of emphasis in fashion away from the skills of tailoring to those based on the skills of draping, inspired by a mixture of sources, including the Greek chiton, the Japanese kimono and the North African caftan. ‘Poiret’s process of design through draping is the source of fashion’s modern forms,’ conclude Koda and Bolton.

Between 1906 and 1911, Poiret revived a high-waisted line, referencing both the Directoire period of the 1790s and the ancient Greeks. He mischievously provoked outrage by appearing at the Long-champ racetrack, accompanied by three young women wearing dresses with the sides slit from the knees showing off coloured stockings. He received even more precious media coverage in London by showing his collection at a tea party organised by Margot Asquith, wife of the prime minister. Poiret was by then a considerable celebrity in his own right, with the élan of a theatre impresario and a swaggering, confident personality that swept all before him. In 1909, he moved his premises to an eighteenth-century mansion on avenue d’Antin and created a veritable fashion empire, kept in check financially only by the conscientiousness of bookkeeper Emile Rousseau. Nor were his customers spared from his dominant, sometimes aggressive personality: Poiret, in his own eyes, could do no wrong. The cardboard sign outside his office read: ‘Danger!!! Before knocking ask yourself three times—Is it absolutely necessary to disturb HIM?’

His glory years saw Poiret move far beyond fashion, developing links with a series of artists, most notably Paul Iribe (who produced a catalogue of illustrations for him in 1908) and Raoul Dufy, who became a lifelong friend. Poiret’s catalogues prompted the creation by magazine editor Lucien Vogel of Gazette du bon ton, which was essential reading for the fashion set in Paris from 1912 to 1925. Poiret’s love of the theatre was reflected in a series of extravagant parties, the most notable being his ‘The Thousand and Second Night’ or ‘Persian Celebration’ in June 1911, where his 300 guests dressed in oriental costume and his wife, Denise, was locked in a golden cage and released like a bird. Erté became an assistant designer for Poiret in 1913, working with him on his theatrical designs. Poiret’s costumes for Mata Hari in a play, Le Minaret, were a sensation, featuring a tunic-crinoline shaped like a lampshade, which Erté said was ‘inspired by the transparent veils of the Hindu miniatures and by the pleated kilts of Greek folk costumes.’

Poiret foreshadowed the magpie tendencies of designers in the latter decades of the twentieth century through his happy plundering of styles from all points east of Paris. From harem pantaloons to kimono coats to Indian turbans, the couturier found inspiration in everything. His colour explosion brought orange, green, red and purple to the fore as never before, marking a break with the understated pastels of the Art Nouveau period. For a while, Poiret was the most celebrated couturier of the age, particularly famed for his coats, capes and cloaks, notable for their sheer lavish use of fabric, often with fur trimmings. By 1913, his love of bold colours and extravagant prints reflected the work of the Wiener Werkstatte, an influential decorative arts company in Vienna. Poiret did much to popularise the design ideas coming out of Austria and Germany (which led to some criticism from French patriots during the First World War).

Poiret always had entrepreneurial instincts and was bursting with ideas for making money. In 1913, he was the first couturier to embark on the conquest of America, touring department stores. Poiret was also the first couturier to give lectures, attracting huge audiences in the United States and across Europe. Despite his overbearing personality, he always insisted that the couturier’s role was not to be a dictator but to be a servant blessed with extreme sensitivity, able to detect the precise moment when a woman’s enthusiasm for a fashion was beginning to wane. His American tour was a triumph, but Poiret returned in a state of shock at the widespread copying of his designs. This led him to push for the creation in 1914 of Le Syndicat de Défense de la Grande Couture Française, of which he was the first president. Two years later, he tried a different strategy, producing reduced-price copies of his own dresses, advertised in Vogue in 1916 and also promoted in America. In her groundbreaking research, American academic Nancy Troy (2003) has shown the contradictions in the way Poiret presented himself as an artist not only to sell to wealthy clients but also to promote the mass production of his designs. The First World War put a stop to grand plans for expansion in America, and any last pretence at financial discipline evaporated after the war. Likewise, after the horrors of four years of war, Poiret’s love of theatrical extravagance struck a false note, contrasting with Chanel’s functional style and the garçonne look. Although Poiret continued to produce many outstanding collections, his heyday had passed, and a period of slow, sometimes painful decline followed.

Behind the extravagant personality, Poiret was a devoted father to his three children (Rosine, Martine and Colin, who all gave their names to the spurt of initiatives in 1911; he was devastated by the early death of Rosine from otitis). He divorced from his wife and muse, Denise, in 1928, telling the governess, ‘Make sure to tell Madame to take anything she wishes.’ In the 1920s, Poiret continued to have no lack of admirers and opportunities. The sadness was that his creative energies were matched by a reckless attitude to money that resulted in years of penury and near ruin despite the constant efforts of friends and admirers to help him out. By 1929, his extravagance led to the closure of his house, and the final years of his life were a depressing downward spiral, exacerbated by the advent of Parkinson’s disease. In 1937, a proposal raised at the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture to grant Poiret a pension was vetoed by Jacques Worth.

However, the later years of his life were not empty and showed that Poiret was still a forward-thinking innovator. In 1927, he wrote a far-sighted article for The Forum magazine, predicting the future dominance of synthetics and plastics. In another groundbreaking move in the twilight years of his career, he designed for both Printemps and Liberty of London in the 1930s. Poiret’s status was fully recognised in 2007 through a lavish exhibition, Poiret: King of Fashion, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, prompted by a treasure trove of clothing from the collection of his wife, Denise, that came up for auction in Paris in 2005: the Met acquired more than twenty pieces. In particular, a pair of 1920s nightdresses, inspired by classical Greek style and worn by Denise, confirm the lightness of his touch and the importance of his influence. But his more extravagant costumes also struck a chord. By the late 1920s, as fashion historian Caroline Rennolds Milbank put it: ‘Poiret’s global exoticism would not seem modern again until the beginning of the twenty-first century, when the haute couture had found new resonance as one of the most dramatic of arts.’

Fashion historian Diana de Marly called Poiret ‘a liberator’ (hobble skirts aside): his lean line marking the death knell of the restricted waist, his narrow styles reducing the need for layers of petticoats. Thanks to Poiret, clothes for women began the shift from burdensome impediment to lightweight and more practical adornment. For Met curators Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton, Poiret ‘effectively established the canon of modern dress and developed the blueprint of the modern fashion industry.’ Poiret was indeed the precursor for much of the contemporary fashion world. Fashion historians are fortunate to have plenty of insights into his design philosophy from the couturier himself, thanks to his many lectures, magazine interviews and a late autobiography. Never mind that his message is sometimes as contradictory as those awkward hobble skirts. At his best, he stripped away the absurdities of late nineteenth-century European fashion and ushered in a new age for his customers, urging women to, in his own words, ‘simply wear what becomes you.’

Further reading: Paul Poiret summarised his own career in My First Fifty Years (trans., 1931). Biographers include Yvonne Deslandres, Poiret (1987); Alice Mackrell, Paul Poiret (1990); and Palmer White, Poiret (1973). Nancy Troy’s Couture Culture: A Study in Modern Art and Culture (2003) highlights the commercial acumen of the couturier. Harold Koda and Andrew Bolton’s Poiret (2007), the catalogue to the Poiret: King of Fashion exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2007, includes an illuminating reappraisal of his achievements.