I’m telling you boys / This game is so fuckin simple.

STEPHEN SCRIVER (1981)

THIS IS NOT the book I was planning to write. That book was going to be called Ear to the Ice, and it was meant to focus on what happened in 1972, complete with bold conclusions to the effect that rather than glorify our game and ennoble us as a nation, what the Canada-Soviet experience did was tarnish and taint and shame us, exposing us as blowhards and bullies and — I had a whole indictment scaffolded up. Sticking with the internal medicine/hockey model, I was prepared to conclude that, really, the only way to think about the Summit was (and is) as a virulent national stomach virus from which we’ve never fully recovered. I wanted to understand why, for as long as it’s been our passion, hockey has never really reflected so well on our national reason and probity. For the title, I had in mind the cowboy trick of listening to railway tracks for distant reverberations. If you think about laying your actual ear down on the ice, though, that’s where the title begins to fail, especially if there’s any kind of actual hockey going on nearby. If you don’t get a skate in the head, it’ll be a puck. That scotched Ear to the Ice.

There was a Walter Gretzky book I never wrote, too. When Wayne’s dad was planning an autobiography, I auditioned for the job of ghosting it. The hockey, obviously, was to be a big part of it, but mostly it was a survival story, Walter having suffered a stroke and recovered. This was explained to me, first by the publisher, next by the man from the Heart & Stroke Foundation who met me in a murmurous underlit restaurant in Brantford, near the salad bar, on a gleaming bright spring day. This was the first of my vettings. It was like descending into a cave, that restaurant, and we sat there looking at one another by the reflected light of carrots and whittled radishes. When I’d passed the restaurant test, I moved on to the house that Wayne built. The family home, anyway: a perfectly regular house on a perfectly pleasant small-town street with three black and lustrous Lincoln Continentals parked in the driveway.

Walter wasn’t home, and neither was Phyllis. The next of my vettings was conducted by Wayne’s brother Glen, whose career statistics you won’t find anywhere online. We chatted. It made sense that he was expecting me to come with readymade notions of what kind of book Walter and I would be writing, a prepared vision. It made sense, yes, but no one had told me. I had ideas, but not as many as I would have had if I’d prepared, plus it was hard to concentrate. Glen had to move the Continentals from time to time, there was some kind of a parking situation that only Glen was authorized to resolve, and I’d chat for a minute to Glen’s girlfriend, then back again to the book, until another Gretzky walked in. I met sister Kim as she passed through, and brother Keith, too. Gretzkys kept appearing from doorways, down staircases, it was like a play we were in, a dress rehearsal of Beckett’s lesser-known Waiting for Brent. (Spoiler alert: he never shows.) And after a while of not really having very good answers for Glen, more and more my mind roamed towards the basement stairs. I could see them from the couch: they were right there. Maybe could we pop down and look at the memorabilia? Walter Gretzky’s basement is second in fame only to his backyard rink, which we did see, or at least the physical space the famous ice had once occupied. It’s dedicated now to a swimming pool. Looking at the pool, not far from the top of the stairs, was as close as I got to seeing Wayne’s trophies in Walter’s basement.

Later, when the publisher called to say they were going with another writer, I think I may have regretted the burst I didn’t make down those stairs more than the book I didn’t get to write with the man I never met. They thought you were maybe too interested in the hockey, is what the publisher told me. Nothing wrong with that, she said, perhaps they just wanted someone who could balance it more with the heart and the stroke.

And the 1972 book? Well, 1972 wasn’t the problem. Yes, it did kind of leave me cold and prone to wincing once I started catching up on what had happened, watching all the games in real time, reading all the books already published on the subject. The truth is, I missed 1972, the original one, so I have none of the foundational memories of those who were there, school cancelled for the afternoon, everybody in the gym watching the TV they wheeled in, Henderson scores for Canada! Nothing. Remember, says my friend Evan, the rumour about Tretiak? What rumour? “The reason he was so good was that the Russians had all his ligaments removed.” I have to shake my head. Evan knows it’s just the kind of the thing I’d love to be remembering. “The great part is,” he says, “we had no idea what ligaments were.”

Abroad was where I was, taken on sabbatical with my parents, both academics. I was six years old, so I had to go along, my brother and sister, too. We lived in an English village, across the bridge, turn right at the pub, down the long pebbly drive. The pub had a name, the Greyhound, and so did the house, as houses abroad sometimes do when you’re six years old: Tanglewood. There was a brick well in the big garden and a wood and a roaming tortoise named Ferdinand. Back near the bridge was the riverbank from The Wind in the Willows, and beyond that, the house where Kenneth Grahame wrote about it, including winter scenes, though no hockey. We watched the river that year, same as Ratty and Mole, but it wouldn’t freeze.

I had no idea what I was missing, being abroad, nobody having taken the trouble to tell me about the hockey history that was about to be made in Canada and the USSR. This may have been part of the plan. What I didn’t know I didn’t worry about. And it’s not as though I didn’t have new interests in England — for instance, tracking down roving tortoises and epic games of kick-the-can at the vicarage. I also took a furious interest in Lord Nelson and what he’d done at the Battle of Trafalgar with just one arm and a single eye and not very much of his life left to live.

In E.M. Forster’s novels, anxious mothers whisk their young daughters out of the country at the slightest hint that they might be in danger of falling in love with the wrong young men. Later, briefly, I wondered if that sort of thing might have happened to me. Maybe my parents had somehow foreseen the way it was going to unfold, all the ugliness of 1972 that no parent could hope to explain, the jingoism and the slashing, chairs thrown onto the ice, throat-cutting gestures. They knew they couldn’t fight with my blood, teeming as it was with hockey. Had they decided to leave the country to prevent their six-year-old from seeing the Soviets toy with our Canadian professionals and — worse still — how the professionals would respond?

I phoned my mother, gave her the conspiracy pitch. She laughed. “No,” she said.

I asked my father, “Were we keeping up with the hockey while we were over there?” He thought about this. “Keeping up how?” I don’t know. Radio Canada International. Taking the train to London to read day-old Globe and Mails at Canada House. “No. Could be. Possibly.”

It’s not as if it would have been easy for him, with his hockey past, captain of the team, Smoothy Smith of yore. He would have had to have been fighting the hockey in his blood in 1972 to exile himself like that.

By the time we left for England, hockey was everything to me. In 1972, other than going to school, hockey was all I was doing. When I wasn’t lining up on the ice for All Saints, I was playing road hockey in Dave Bodrug’s driveway or knee hockey in Peter Wearing’s basement. I studied The Hockey Encyclopedia with a young monk’s devotion. Ian Lamont and I, serious stockpilers of hockey cards, would fill entire weekends with endless bonspiels of leansies, topsies, and farthies. We played pretty much continuously from 1971 through 1975, when I gave all my cards away — a huge mistake, I realized almost at once, triggered by the false impression that nine was the age at which you outgrow both hockey cards and the foresight to hang onto them long enough to sell them on eBay, whenever it might be invented. I hadn’t yet learned any of the aphorisms about the place hockey colonizes in Canadian society, our hearth and our heartbeat, our national conversation, our theatre, our daily bread, the church where we worship, our very faith and creed — I didn’t need to know any of that, because my blood knew.

The sheer broadside brutality of the Royal Navy’s fighting fleet circa 1805 served me well during that year in England, fulfilling my need for obsession, and for that I’m grateful. When we got back home to Canada in the spring, though, it was all hockey again. I don’t have much of a memory of the summer of 1973, but I’m assuming some of it was spent absorbing the free-floating atmospheric national joy left over from when we’d beaten the Soviets. Friends must have told me what happened, if only so I could play my part in the road-hockey reconstructions. Without knowing much about it, I was pleased and proud. We’d won, hadn’t we?

That’s the thing about hockey-blood, it updates automatically, like the operating system on my Mac.

THERE WERE FOUR games in four Canadian cities in September of 1972, you’ll remember, four more in the enemy capital. At home, we lost two, won one, tied another. We lost again in Moscow, then won the final three games. No need to worry about the three European exhibition games. Final score: yay us!

I came to fret about how it had all played out: the shock of that opening loss, the nation’s agitation, distraught Phil Esposito, bad Bobby Clarke, overwrought Paul Henderson. No sooner had I consoled myself by recalling the skill with which Pete Mahovlich scored short-handed in Game 2 than I’d happen on some ugly reminder of how messy the whole enterprise was: Canadian allegations, for instance, from Game 7 that Vladimir Vikulov kicked Yvan Cournoyer (once) and Gary Bergman (five times). I was irked at first when I read about a Polish reporter in Moscow who told his readers that because the Canadians, so much older than their Soviet opponents, were still somehow faster and stronger and more spirited, it probably meant they were on drugs. Later, though, I wondered whether this wasn’t a kind of a compliment: to some, our healthy, free-range hockey looks hopped-up.

I loved the stories about how the devilish Soviets schemed to steal the three hundred steaks and eight thousand beers Team Canada brought to Moscow. (We also imported two hundred litres of Finnish milk.) And I continue to revere the sweaty rawness of Esposito’s Vancouver speech — “To the people across Canada: we tried, we gave it our best” — after the home crowd booed the Canadian loss. The desperate wheedling heartfelt passion of his plea was like the voice of the country giving itself a talking-to.

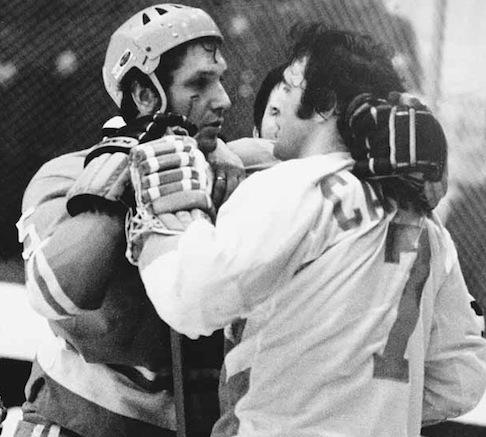

Icy niceties: Alexander Ragulin (left) discusses the situation with Canada’s voluble Phil Esposito during Moscow’s Game 7, September 26, 1972.

I was thoroughly chuffed to read, without entirely believing, that on the day of the final game, not only did Canada’s federal election freeze in its tracks, but crime and punishment, too, as courts were adjourned and the crime rate dropped to nothing. I lapped up new Summit Series books as fast as they appeared, from Dave Bidini’s tiny radiant A Wild Stab for It (2012) to the no-stat-left-behind immensity of Richard Bendell’s 1972: The Summit Series, published that same year.

I finally watched the games, loading in the DVDs over the course of a weekend up north. My wife, Sarah, checked in on the score now and again, and so did the friends who were staying. Mostly it was just me and my friends’ eight-year-old son glued to the thirty-six-year-old TV feed from Finland. It was all new to him, too, though he knew things I didn’t. “Bobby Orr is playing for the Russians,” he mentioned halfway through the first period of Game 5. Nothing I could say would convince him otherwise. Before I brought in the books to contradict him, he’d identified Orr on the ice and — fine, have it your way, he looks good, doesn’t he? We were both disappointed when Paul Henderson scored, but I told him not to worry, there was still another game to go. “The Russians win,” I said. I later felt terrible about that.

In truth, Orr hadn’t been healthy enough to play. Dave Keon’s absence concerned me too; he should have been on the team, shouldn’t he? Not to mention Bobby Hull and, on the Soviet side, Anatoli Firsov. I wished Anatoli Tarasov was still coaching the Soviets instead of having been dismissed for murky reasons earlier that year.

These contributed to my disaffection, as did the mayhem of the two Swedish games we played in between Vancouver and Moscow. And also:

And the Canadian team left the ice after the devastating opening game in Montreal without shaking hands. Everybody thought we were soreheads, admitted coach Harry Sinden later, but, hey, who knew you were supposed to shake? Other than Ken Dryden: he shook hands. You learn only when you lose, Dryden said. He couldn’t believe it, but not a single NHL team sent scouts to the games in Toronto and Montreal. “Setbacks can be very useful in sport, since they help analyze correctly your flops and excite the striving for revenge,” said Tarasov. “For some unknown reason, defeats do not worry the Canadian hockey leaders.”

I was left queasy by the idea that in winning, Canada had planted a secret seed in Russian hockey, the noxious weed that grew inside their game and choked it. Bobby Clarke has suggested as much:

It used to be that when two national teams would get out on the ice, you could see the difference in styles immediately. Now everybody plays the same type of hockey. And it’s the North American type. In our time Soviet players never dumped the puck into the zone. They would rather turn around at the blue line and pass backwards to start a play all over again. Now they do it our way more often. I think that after 1972 the Russians learned that it’s more effective to get the puck into the opposite end and play physical hockey there.

After the Montreal game, Ken Dryden questioned whether he would ever be able to cope with Russians. Wandering the city, he ate terrible hamburgers in an awful restaurant. He wondered whether it was all a bad dream. He ran into the Montreal sportswriter Red Fisher, who was as bereft as he was. They both felt as though something had been taken away from them.

They needn’t have worried, of course, because twenty-six days later, Canada was crime-free and triumphant. Bobby Orr said that it proved we were the best hockey players in the world. For the games in Canada, he opined, the only real problem had been conditioning. Asked about Canada’s many Moscow penalties, he said, “Players like Paul Henderson, Gary Bergman, and Bobby Clarke never look for trouble in the NHL. If they’re losing their tempers here there must be some reason for it.”

I CONFESS THAT I didn’t read a single hockey book either on the nine-and-half-hour flight from Toronto to Moscow or during the week I spent in Russia in the summer of 1997, following the hockey players. There were three of them: Viacheslav Fetisov, Vyacheslav Kozlov, and Igor Larionov. They were Detroit Red Wings at this point, and having won the Stanley Cup that spring, they were exercising the champions’ right to take the trophy home to meet the family. As big a deal as it was for the NHL and Moscow, it was a much bigger one for Larionov and Fetisov, legends of Soviet hockey who’d also railed against the strictures of its systems. After a long struggle they’d escaped — soon enough that their giant talents weren’t exhausted when they came to play in North America. Both had written autobiographies, and I was looking forward to sitting down in Moscow to talk to them about the journeys they’d taken and the hockey they’d played.

And one day, maybe, that will happen. In Moscow, only once did I see the hockey players seated; the rest of the time they were on the move, enclosed by crowds of family, friends, NHL officials, owners of the Detroit Red Wings, journalists and photographers, fans, startled tourists who wondered what the fuss was about, and a few of the young army recruits you used to see loitering all over Moscow at that time (often by car windows asking for money when the traffic lights turned red). When I wasn’t grumbling at the hangers-on who were blocking my view of the hockey players, I did my best to get out of the way of those people whose view I was obscuring. The night I did manage to shake Igor Larionov’s hand, we were in a Canadian bar, the Hungry Duck, where the beer was Labatt’s. “Congratulations,” I said, just before he sat down at a table with no place at it for me.

WHATEVER ELSE RUSSIAN blood contains, hockey wasn’t in the mix originally: it had to be introduced. There’s a song they sing sometimes at Russian hockey games — you can find it on YouTube — that includes the verse:

The most fitting game for our Russian guys

Was accidentally born in Canada

The story of how Russians came to hockey is altogether clearer than ours, but it does come with a bit of a tangled-up provenance, some mist, and a Chekhovian touch of men arguing offstage. Here’s how I understand it. Before 1946, Russians mostly played soccer in the summer and bandy — russki hokkei — when winter came. They’d been doing it, in one form or another, since Peter the Great’s time. Canatsky hokkei (ours) wasn’t unknown, especially in the Baltics, but mostly they bandied, chasing a ball, with eleven-man teams skating on a rink the size of a soccer field. Sticks were short and curled and wrapped in cord.

What happened in 1946? Possibly it was a case of Moscow Dynamo, the famous soccer club, touring Britain in 1945 and in their spare time attending a game in which visiting (probably military) Canadians were playing hockey. Like so many others before and later, they were captivated. Clarence Campbell, still a soldier, was in England at this time, prosecuting Nazi war criminals, and that’s what he thought happened.

Ah, the Soviets. They had such a hockey plan, a big one, which was more or less the same as their foreign policy: they wanted to rule the world as soon as possible. Hockey-wise (if not geopolitically), we thought they were adorable, trying so hard with their funny helmets and their aluminum shin pads. At first the notice we paid was none. The next stage was when they started to look pretty good and we thought, Not bad. They got better and better. They started beating the teams we sent over to Europe, which was kind of rude, especially since we’re talking here about the East York Lyndhursts. It wasn’t as if they were beating our best teams. Not that we’d even bother to play them with our best teams. What would be the point?

When the first league started up in December of 1946, some of the players had never seen a puck before. The plan was to run a season lasting two months. Boris Kulagin was one of the draftees. “We did not have big crowds,” the coach of the 1972 Soviet team said, “and we were seen as some kind of fools for playing a completely alien game.” Vsevolod Bobrov was one of the stars of the Moscow Dynamo soccer team when it travelled to London in 1945. When he took up hockey, he was bewildered, helpless. However, he floundered but briefly; soon “he made the puck obey him.”

An American writer named Drew Middleton went to see an early Moscow game in January of 1947: Red Army versus Dynamo. He reported that they might give a New Jersey high school team a good match “on an off-day for the latter.” A player shouted “please!” to a teammate when he wanted a pass. In the intermission, a song called “Let Mother Discover We Are in Love” gusted from the loudspeakers. In his opinion, neither Red Army nor Dynamo would be going anywhere fast until they dispensed with the long woollen underwear they wore in favour of proper hockey togs. “The drawers,” Middleton wrote, “seemed to get in the way.”

At the rink at the Moscow Physical Training Institute, the boards were just six inches high. Local journalists who watched couldn’t get a grasp on the game. Players struggled to lift the puck off the ice. The new stick was a puzzle. The blade was absurd. Bandy goalies go stickless, so to have one thrust on them was irritating. They couldn’t get used to it. They flung it away.

“We learned the game out of a void,” Anatoli Tarasov wrote.

Kulagin tells of an early Canadian offer to send coaches, but the hockey authorities agreed that the best way to learn the game was by themselves, organically, free of foreign additives. Although another version of this is that when the Soviets proposed to Canadian officials an exchange of coaches after the 1954 World Championships, they were snubbed. No one would come to watch Russians play in Canada, they said they were told.

At home, there were those who said that Canadian hockey was folly. Boris Arkadyev, the national soccer coach, for one. Writing in the newspaper Sovsport, he reproved those who, he said, wished to “bury alive” the Russian form of the game, which he recommended as a more practical winter pastime for soccer players.

Tarasov was one of the Russian hockey pioneers, players “of the first call-up” is his phrase. Later, North Americans came to hear about his dominion over the Soviet game, to size him up as the Plato of Russian hockey, and maybe also its Dalai Lama. The first defencemen of Soviet hockey never hit. There was no ramming, Tarasov writes. “They played quite a soft game, almost gentle.” Sometimes they felt awkward, embarrassed, playing rough teams. They stayed calm. There was no retaliation. They were considerate. Patience would win. “Victory, we thought, is good compensation for injustice.”

The first real test came in the third February of Russian (Canadian) hockey in 1948, when LTC Prague arrived in Moscow to play a series of exhibitions. Too soon, some said. Tarasov was one of the organizing coaches. His brother Yuri played, and so did Bobrov. Elbow pads and knee pads were “cotton wads,” and players wore soccer shin pads. “Helmets and cups were non-existent in our country in those days,” Tarasov notes. The only skates they had were long-bladed. But from bandy they brought speed and pinpoint passing. Tarasov says they won that first game — 6–3 — on desire alone. Collectivism and valour perplexed the Czechs.

The first indoor rink in the Soviet Union didn’t open until 1956. No worries. “The players,” said Tarasov, “felt much better on outdoor rinks with a slight wind and frost.” If you read the Russian hockey books in translation, there’s plenty of lusty ideology: Ice hockey is the display of a man’s best qualities: kindness and courage, fidelity to one’s comrades and moral stamina. There’s no mention of violence. A lot of tough talk, yes, but it’s mostly in a theoretical vein, so that when Alfred Kuchevsky says “ice hockey is a fight,” he doesn’t mean a punching-fight so much as “an opportunity to prove that you’re stronger than your opponent. To prove you’re a real man.” When the other fighting does come up, it’s a perplexity — “sometimes the spectators are puzzled: isn’t there too much rudeness in the game?” — or a disgrace to the game. “Respect towards one’s rival does not allow a player to behave dishonestly, to attack, for instance, a player who falls down.”

“Personally, I seek happiness in ice hockey,” confides Alexander Ragulin, Merited Master of Sports.

Eventually, reading the Russian hockey books you can without a translator’s help, you get to the secret. It’s a wonder they give it up so readily.

[E]ven when the boys leave hockey they will take into life with them the most valuable human qualities acquired in the game: a readiness to help your team-mate, friendship.

Hockey helps a young man enter adult life strong and courageous.

There is also a feed-back in this sport, however — most significant success comes to kind-hearted and good people, to those who honestly and faithfully serve the interest of their team, their teammates.

ON THE MORNING of the day I followed the hockey players to Voskresensk, I walked along the Moscow River down below the Kremlin and tried to take a photograph of the man with the small brown bear on a leash. The man nodded when I gestured with my camera and I was all ready to go until he spoke what may have been his only English words: fifty bucks. I probably would have paid if this were a hockey-playing bear; as it was, I kept going, on to the Metropole Hotel. With a reporter from the Detroit Free Press, I spent my money on hiring a driver instead. In his big mustard-coloured Mercedes with no seatbelts, the three of us headed out of the city, downriver, following Larionov and Kozlov as they carried the Cup to see their hometown, an hour or so to the southeast. (Fetisov is a Muscovite.) On the road, the North Americans in the car discussed everything from anxiety and fear to the possible cultural reasons why we had to drive so fast and pass every last slow-moving beet truck on the highway when oncoming traffic was equally fast-speeding and constant.

In addition to the beets, we outran the minivan carrying the Stanley Cup. We came into Voskresensk through the concrete district, slowing down briefly in the dusty-car quarter. On the far side of town the sky was filled with fuming clouds so thick that smokestacks had formed underneath, dangling like stalactites. A crowd was already gathered at the rink when we got there. As we pulled up, they gave us a cheer that died of disappointment as soon as they realized we had no hockey players with us and no silverware to show off.

Over and beyond Larionov and Kozlov, the list of local hockey talent is long, and lush with surnames like Ragulin, Kamensky, Markov, Zelepukin. You can’t really help but echo the question that’s at the front, if not the centre, of Larionov’s autobiography: Why is Voskresensk the hockey capital of the world? It is remarkably Peterboronov when it comes to size and proximity to a larger city. Rivers help define both cities (Otonabee v. Moscow), as do industries (Quaker Oats and General Electric in Peterborough v. chemical works for Voskresensk — the hockey team is called Khimik, or Chemists). With several dozen other people, I climbed up to the roof of the Sports Palace for a better view. It wasn’t much: trees and drifting dust, rooftops, cloves of church steeples. Larionov refers to the city as out of the way and God forsaken (sic). According to him, the reason he and others found and thrived at hockey here comes down to one man, a famous coach with a passion: Nikolai Epshtein. That’s it; that’s all. Nothing in the water here but heavy metals.

Cheering greeted the Cup in its minivan, along with swarming and reaching and rubbing. If it’s true that you’ll never win the Cup if you touch it without having played for it properly in the NHL, then I watched a whole generation of Russian children and their mothers curse themselves below me. Inside, the rink was modest, smaller than the Memorial Centre at home. I may have been hoping for a big Lenin portrait down at the far end; there was none. It was as dim and as close as the inside of a dryer, and it took a moment, coming in from the rooftop, to see that there was second crowd waiting in here in the stands. On the ice, Minor-leaguers in yellow Khimik uniforms stood beside stooped bemedalled veterans and, over by the penalty boxes, a battalion of drum majorettes.

I don’t know that the speeches touched on the history of Russia going back to the first tsars, but they did go on for a long time. If they included any jokes, no one was laughing. I walked around the ice taking pictures of old soldiers and young goalies, at the risk of offending the majorettes.

Later I read that Larionov’s grandfather spent fourteen years in a labour camp for something unflattering he said about Stalin. His family paid, too. They were banned from Moscow and exiled south to the chemical city.

BECAUSE IT WAS written in my notebook that Valeri Kharlamov was born “near the Sokol subway stop,” I went there to take a look, once we got back to the capital. In 1948, his mother was in an ambulance on her way to Maternity Hospital Number 16 when he was born. For me, it was a fifty-minute round-trip from the hotel, and while there was nothing really to see when I surfaced from underground, just more low sandy-coloured blocks of apartments and many grim uncrossable lanes of traffic, I felt like it was worth the journey.

I’ve read as much as I can about Kharlamov, and if I end up learning Russian it will be to start on his autobiography, Хоккей — моя стихия (1977). A measure of his importance that’s greater than any paltry pilgrimage of mine is the minor planet that’s named after him. Proper Canadian procedure for honouring hockey players is insistently terrestrial: we raise monuments, sometimes we brand rinks or roads. As Wayne Gretzky, you get it all: statues in Los Angeles and Edmonton, a Drive in Edmonton and a Way in Toronto, and in hometown Brantford, a Parkway and a Sports Centre. Kharlamov’s eponymous Ice Palace is in Klin, northwest of the capital. I didn’t get there, and I can’t say where in the cosmos his planet is, or what its atmosphere might be like, though I do know its number: 10675. If I wanted to guess, I’d say that it looks not unlike the geographer’s planet in The Little Prince.

Late as I was in acquiring them, lots of my best 1972 memories are of Kharlamov, who introduced himself that first game in September by scoring a pair of sublime goals. Canadian coach Harry Sinden says that the only emotion the Russians showed that night came when Phil Esposito punched one of them in the face — and the guy grinned. Sinden doesn’t say who it was, but I can’t help casting Kharlamov in the role, smiling with sincere unruly happiness rather than mockery or sarcasm. Kharlamov’s first goal stunned our team with its magnificence, though they didn’t want to let on at the time. “He’s a helluva hockey player,” Sinden was finally able to concede.

Once we discovered him, Canadians liked how tough Kharlamov was. He had sand, he had sinew, he was as resilient as he was imaginative. This Chagall of hockey, wrote Lawrence Martin; the deadly little scorer, Frank Orr called him. “He had more moves than Nureyev,” Ken Dryden said. Harold Ballard wanted to pay CSKA Moscow a million dollars to bring him to Toronto. Kharlamov’s was the wrong generation, though: it was the next one that managed to leave the Soviet Union behind.

If he couldn’t come to play for Western cash or Stanley Cups, we in Canada nonetheless showed our appreciation with our sticks and our hips and our elbows. I’m sure it didn’t feel like it at the time, but in Game 6, when Bobby Clarke axed at Kharlamov’s already injured ankle, he delivered on our behalf the highest hockey honour we could bestow: a Sher-Wood Order of Merit to go with his Soviet Medal of Labour Valour. In film and fable, Clarke was under orders, though he’s denied it. Either way, it wasn’t a random hobbling. Clarke’s chop was specific and heartfelt, guaranteeing the honouree a lifetime’s supply of admiring Canadian abuse, renewable any time his team came to North America.

Descriptions of Kharlamov’s goals often have the word dancing in them, and sometimes the phrase he loved to stickhandle. Against the Toronto Marlboros in 1975 he scored a goal that because you weren’t there to see it, you just would not believe, unless you watch a lot of Star Trek. “It was as if he had disintegrated on his way over the blue line,” Jim Proudfoot wrote, “only to reassemble his molecules on Palmateer’s doorstep. Better plays are just not made.”

Vladislav Tretiak said his effort, the way he strove to be the best, should be taught in every hockey school. In personality, said Tretiak, he was like the great cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin: “similarly unaffected, bright, and modest. Fame did not influence his character — he remained benevolent, open to all, cheerful, and always smiling.” His favourite food was pancakes. In Montreal in 1972, Dryden noticed that he drank six or seven Cokes for breakfast, same again at lunch and supper. When he came to lunch, the mood of the team changed: everyone laughed.

Later Jim Proudfoot reported that the Canadian players were calling him “the Derek Sanderson of Moscow” for all the “punishment” he dealt out to everybody who approached him. In return, the Canadians accorded him “a thorough going over.” This subtle narrative, that Kharlamov got what he deserved, is picked up in Canada Russia ’72. Movie-Bobby Clarke hates him from the start. “Eat shit, you little prick,” is Clarke’s first — only? — line in the whole epic. Later, we watch assistant coach John Ferguson whispering in Clarke’s ear. Movie-Paul Henderson looks horrified.

In 1974, when the WHA took a team to Moscow for the less-famous follow-up with the Soviets, Canadian defenceman Rick Ley felt he’d suffered insult and indignity from Kharlamov after the sixth game’s final whistle. Canada had lost 5–2 and Kharlamov had “jostled” and grinned at Ley. So Ley didn’t hesitate to punch him to the ice. Actually, the newspaper reports say he flew at him, punching with both hands, continuing the onslaught when Kharlamov was down. If Soviet coach Boris Kulagin didn’t understand the nuances of our Kharlamovian rituals — “Under Soviet law, he should be jailed for fifteen days for attacking and injuring our player,” he said — the man himself knew what was going on. The next day, Ley was waiting for him after practice. Sorry, he said, for punching you in the face, nothing personal, just got frustrated. Kharlamov said he understood. The two men shook hands.

Ed Van Impe was the last Canadian to remind him of our national respect, I think. This was in the game in Philadelphia in January of 1976, just after CSKA played its famous New Year’s Eve game against the Canadiens in Montreal. Van Impe dropped Kharlamov to the ice with a nasty blindside check. When no penalty was called, the Russians refused to play on. They came back, under protest, to lose. Another Flyer defenceman, Moose Dupont, said he thought Kharlamov was playing Hamlet when he went down. “They’re not so great,” he said. “They looked like fools today.” That February in Innsbruck, Kharlamov scored the goal that won the Soviets the Olympic gold medal.

He got married in the spring. Two weeks later, Kharlamov and his wife were in their car on the Leningradskoye, the road of his birth. The car swerved off the road and hit a pole. Kharlamov’s legs were broken just above the ankles, his ribs were fractured, his brain concussed. All that summer he lay in a hospital bed. As soon as he could walk he was at practice. “I was good at first, not so good later,” he said. In 1981, still active with CSKA, he and his wife were involved in another highway collision; this one killed them both. Kharlamov was thirty-three.

The back of a Russian DVD I watched bears this frail found poem of an English translation:

We should be proud,

that in our country of veins

such person

and hockey player

Valeri Kharlamov.

Twice Olympic champion,

the eightfold world champion and

the sevenfold champion of the Europe.

Its game amazed imagination.

In its life was a lot of fatal and mystical.

Valeri was born in the machine

and has died too in the machine,

in the age of 33th years.

It was the unique person. It all loved.

The Stanley Cup and I met up again a few more times before we had to head home to Toronto. There was a press conference at the Ministry of Sport and a big buffet lunch (with caviar and vodka) at the CSKA Hockey School. We attended a hockey game together, too, which is where I bought my white CCCP sweater that I still wear for shinny, number 8, with Larionov’s name across the shoulders.

On the Monday, we took a walk on Red Square, just me and the Cup and dozens of its admirers. I’d been in to see Lenin a few days earlier on my own, and I had no real desire to gaze at his slumbering raw-potato face again or to be hurried along by the guards in the big hats who refused to answer questions asked in English about how often he changed his spotted tie. Still, I would have been glad to go back with Fetisov if he’d invited me to join his wife and kids when they took the Stanley Cup in for their private visit with the Chairman of the Council of People’s Commissars of the Soviet Union. In life, the last thing Lenin would have known about it, assuming he was paying attention before he died in January of 1924, was that Frank Nighbor’s Ottawa Senators were looking like a good bet to repeat as champions.

EIGHT YEARS IT took the Russians to catch up on the ice. Back in Canada we’d developed a cruel model for Europeans embracing hockey. First we welcomed the acolytes, arms open, big hug for loving our game. We gave them as much support as possible, sticks and pucks and skates, coaches, mentors, all on the condition that they never rose as a hockey-playing nation to anything above mediocrity. As with the pesky North Koreans and their nuclear program, we insisted on being allowed to send inspectors every once in a while to beat them 22–0 and thereby verify that they weren’t producing weapons-grade hockey that would one day devastate our pride and dignity.

This worked well, year after year. Until the spring of 1954. Hockey Pictorial framed the health crisis that was developing thousands of miles way:

Hockey’s Biggest Headache:

What Will Canada Do

About Moscow?

The East York Lyndhursts had travelled to Stockholm to represent Canada in the World Championships. The Lyndhursts were a Senior B team from Toronto and they did fine right up until the final, when they met Moscow Dynamo. Hockey Pictorial’s Bob Hesketh described the distress that resulted back home:

Startled Canadians choked on their breakfast cereal as they split their morning papers at the sport page and read that Russia had defeated Canada in a game of hockey. Smugness fell inert to the floor as though it had been struck by a poison dart.

The score was 7–2. When the second-place Lyndhursts straggled back home, the men from the morning papers were waiting. First to touch down in the terminal was centreman Eric Unger. Reporters discovered him in the bathroom at the Malton airport, where they squeezed a confession out of him. “I don’t know whether I should say this or not, but they outplayed us by more than five goals in that one game.” The Soviets weren’t good stickhandlers, but they could skate and they sure knew how to pass. On their bench during the game, they had twelve guys in black coats and black fedoras. At the hotel, the players wore track shoes with no laces — Unger didn’t know whether maybe that was part of their training.

The Swedish fans had been pro-Russian, as was the press. When Lyndhursts goalie Don Lockhart disembarked, he revealed that all the Soviet shots he’d faced had no fakery in them, they shot straight on. “If they played our rules, we could knock them flying.” They were so weak, another player said, that even the Czechs could have beaten them, if they hadn’t laid back. Right winger Bill Shill was covered in Russian bruises from Russian sticks. “They have plenty of speed but no actual hockey ability,” he said. Their equipment was pretty poor, and too much — they even wore a belly pad. “I would have liked to have taken them on in a four-of-seven series,” Eric Unger said before the reporters let him go home.

Conn Smythe had a better idea: the Toronto Maple Leafs would go to Moscow that very May to take on all comers as long as one of them was Moscow Dynamo. It wouldn’t cost the Soviet Union a ruble, this generous offer of international hockey goodwill. The chairman of the board of Maple Leaf Gardens fired off a cable to the Soviet ambassador in Ottawa to seek permission. This was “a national blot,” he said, and it needed to be cleansed. Smythe’s assistant, Hap Day, wasn’t so sure. He was going on holidays after the season ended, not to Russia. And the coach, King Clancy, had to work. He could only go, he said, if Russia was within seven miles of Ottawa, where his construction business needed him. Clarence Campbell worried that the team would end up trapped behind the Iron Curtain. In the meantime, a fan could dream, and so could a capitalist. Watch out, Red Square, for Ted Kennedy! Hey, Nevsky Prospekt! Ever met Tim Horton? All our vengeful behemoths, over there, unblotting the nation. Rudy Migay! Fern Flaman!

It just wasn’t to be, though, and almost as soon as it was proposed, the plan had to be stowed. Not that the Leafs weren’t welcome, the Russians politely said, it was just that by the time they got there in May, all the rinks in Moscow would be melted.

SWEDEN HAD THE words for hockey before it got the actual game: I picture them drifting like catkins over snow, waiting for their future to arrive, smäll (whack), klampa (clump), sus (swish), slagsmål (rough house), slagsmål (scuffle), and slagsmål (fisticuffs).

The Swedes didn’t need hockey. They were doing fine, in 1920, with none. I don’t know what it is about their national blood that resisted it, but for years of Swedish history, the people did extremely well with football and skiing, and also bandy. The bandy microbe was coursing strongly in the national bloodstream for a long time before the men with hockey in mind met at a Stockholm restaurant in 1919.

They were three: a sportswriter, the guy in charge of Swedish soccer, and an American former speedskater who worked for MGM. With the first Winter Olympics coming up in less than a year, you’d think maybe they’d elect to take it slowly, go to Belgium to observe, aim for the 1924 Olympics. No. They couldn’t wait. Hockey — ishockey — was too good to resist. They wanted in. I just wonder, if they’d known the pain that lay ahead, the abuse Swedish hockey was in for, would that have squashed their enthusiasm?

There was lots of good stuff to come as well, though — and glory. There would be Sven Tumba and Ulf Sterner, not to mention Peter Forsberg, and what about Olympic gold medals and the Sedin twins and Henrik Zetterberg? Tumba’s hockey books include the not-so-definitive Tumba säger allt (Tumba Says It All) from 1958 and 1995’s Mitt rika liv eller den nakna sanningen (My Rich Life or The Naked Truth), for neither one of which have I, to date, collected enough Swedish to read. Tumba was the first European-trained player to be invited to an NHL training camp, in 1957, but when he didn’t make the team, he decided not to sign a contract with the Minor-league Quebec Aces, which would mean losing his amateur status. He went home.

It was going to be great. Except for, somehow, the Swedes would have years of Canadian derision to navigate, invective, slurs, punching. We called them “Chicken Swedes” and our crowds chanted: “Kill the Swede!” We didn’t like them. It’s better now, but it’s only fairly recently that we decided to forgive the Swedes for whatever it was we felt they did to us in the course of embracing hockey. Was it something they said in 1920? Did they look at the Winnipeg Falcons the wrong way as they succumbed 12–1 in Antwerp?

Is there solace in the fact that we looked down our noses for so long at the Americans, too, even as we played in their cities in front of their paying customers? Playing for Boston in 1926, Duke Keats said that 99 per cent of American fans had not the foggiest idea what was going on in front of them. Steering the Rangers in 1928, Lester Patrick pointed out that American players didn’t start out skating early enough, which was why they couldn’t develop a proper full-leg stride, so you could always tell what they were going to do on the ice.

If anything, the Swedes played as Canadianly as we did right from the start. The Russians might have refused our coaches, insisted on going it alone, but the Swedes were all too willing to follow in our tracks. Before they arrived in Belgium, they only ever practised with bandy sticks and a rubber ball. They wore no shin pads. What they lacked in finesse, they made up for in ardour. “They didn’t spare one another in practice,” reported a Canadian observer, “but smashed and crashed each other into the boards without the slightest hesitation.”

The very first game they played in 1920 — it was actually the first game ever in Olympic hockey history — they swamped the poor Belgians 8–0. The home crowd didn’t like their tactics, which were described as rough and ready: they knocked down any Belgian as soon as he got the puck and the Canadian referee had to ask them not to carry their sticks so high. When the Falcons got home, they said the Swedes would be hard to beat in a year’s time. They’d joined the Czechs in buying all the Americans’ equipment and tried to buy the Canadians’, too.

So that was encouraging. It had to make us proud. Why then, after that, is the rink of our dealings with the Swedes so littered with kiv (squabble) and ruskighet (nastiness)? I’m not talking here about the early rudeness of wallopings — 22–0 in 1924; 11–0 in 1928 — but of the increasingly hostile attitude we took to the Swedes.

They were always whining, said the president of the Ontario Hockey Association in 1961 when the Trail Smoke Eaters toured Sweden and defenceman Darryl Sly was charged by police for assaulting a Swede on the ice. You never heard a peep out of the Czechs or the Russians; maybe the answer was to avoid Sweden altogether. Sly, for his part, said the reason that Swedes got hurt was that they were soft.

“This is not hockey,” Swedish papers said. Next time, maybe, they’d have to bring in Sweden’s national boxing squad.

The Swedes buckled down, studied harder. While the Soviets and Czechs went to war at the 1969 World Championships, the undercard featured Sweden undoing Canada 5–1. Afterwards, the Swedes bemoaned Canada’s rough play. Swedish coach Arne Stromberg complained about the refereeing and catalogued his wounded: “This was not one of our best games. Our team was trying to avoid being slaughtered by these boys.”

Ulf Sterner was speared under the arm “and the blood flowed constantly.” Lars-Erik Sjoberg had “a broken lip.” Sterner returned to knee Canadian goalie Wayne Stephenson, who left the game with a bad charley horse.

It’s hard to say when the counterattack had begun in earnest. As early as 1949, when the Sudbury Wolves travelled to Stockholm for the World Championships, the local press called them “dangerous men.” When it was time to play the home team, thousands of fans tried to prevent the Canadians from entering the rink. (Maybe. The fans may simply have been trying to get in themselves.) The game, a 2–2 tie, was “bitter.” On the second Swedish goal, a spectator reached over the boards and held Joe Tergesen’s stick. Police had to escort the Canadians in and out of their dressing room.

“We in Europe are trying to make ice hockey a little more human,” said a Swedish official. “We do not like the North American tendency to brutalize the game.”

They were crafty, those Swedes. In 1965, they tried to outflank us psychologically, with the announcement from their national hockey federation that money was being set aside to provide financial assistance to Canadian amateur hockey, essential as it was to the well-being of world hockey, if sadly underfunded. Fuck you very much, Canada said.

In 1969, a Canadian ex-pat living in Stockholm explained the attitude of the Swedish press: “Canadian hockey ranks probably somewhere below the slaughter of baby seals.” He kept a scrapbook that he’d filled with local newspaper clippings devoted to Canadian visits over the years. In 1968, the newspaper Aftonbladet sent a lawyer to the rink to watch the Canadian Nationals. He cited nine instances where players would be charged if they’d done what they did off the ice instead of on.

In 1973, the Toronto Maple Leafs signed two stars of Swedish hockey, Inge Hammarstrom and Borje Salming. For their first road game of the season, the Swedes got to visit Philadelphia. Dave Schultz punched Salming whenever he got the chance. “I don’t think they like Swedish boys,” Salming said. “They don’t play hard, they play dirty. But it’s no problem.” Flyers defenceman Ed Van Impe, who took a five-minute penalty for spearing Salming, said it was accidental — he was falling at the time.

Here’s what Anatoli Tarasov had to say about Ulf Sterner:

Can anyone else in world hockey, including the professionals, pass the puck with such skilled faking, with such precisely judged force? His passes are not only mathematically precise, timed just right, but they are very easy to receive; it comes to the blade of a teammate’s stick almost as if carried by hand.

The Rangers signed Sterner in 1964, then sent him down to the Minors, beckoning him back when he started to score. The Washington Post reported: “The rugged Canadians who dominate professional hockey consider it a matter of routine to give any rookie the test — a physical pounding, both legal and illegal.”

It was said he couldn’t get used to the hitting. The Rangers played harder against him in practice, he said, than they did against the opposition in games. Down with the farm team in Omaha, he put the puck in his own net on a delayed penalty, and oh, how the North Americans laughed.

“I like rough hockey,” he would say, and then, waving his stick: “But this I don’t like.”

Eventually he gave up. “I suspect that Ulfie has never recovered from his NHL experience,” said Ken Dryden. And that seems to have been the case. In 1963, he clobbered a Swedish fan with his stick, which he also later used to attack a Finnish opponent. In both cases the talk that he’d end up in jail came to nothing. He was suspended for two months in 1970 for punching a referee. In 1972, it was Sterner who cut Wayne Cashman’s tongue in two with his stick.

THE REVEREND MR. Wood wasn’t attacking the game itself. We should be clear about that. His complaint was precision itself, a finger pointing out a specific transgression, a matter of timing, rather than a general indictment. Just a strong opinion, judging from the report in the Canadian Independent in 1890.

It was a winter’s Sunday in Ottawa, and at the Congregational Church at the corner of Elgin and Albert, Reverend Wood gave a Bible reading on the law of God in regard to the Sabbath and the example of the Saviour and His apostles to its observance. Word had come from the governor general’s residence, Rideau Hall, that people were playing Sunday hockey on the vice-regal grounds. Wood didn’t like to believe it, but how could he ignore the letter in the paper from someone who’d taken part and “gloried in his shame”? It was unbelievable. Set aside God for a moment: What would Queen Victoria think? “He was sure Her Majesty would not allow such a thing in the grounds of Windsor Castle.” On he railed. Wealth, he reminded the congregation, was no excuse: the divine laws apply to rich as to poor.

It’s good for hockey, healthy even, to sit in the pews and listen to the naysayers. Because there are, no doubt, plenty of people who have problems with the game, and not just in terms of Sabbath-breaking. It helps to look the doubters in the eye, and to hear their concerns. Maybe we can help them. The thing, I think, is to distinguish the veins of complaint, to separate the merely indifferent from the mildly irked, the fatally bored from the outright haters.

Roger Angell says that “bad hockey is the worst of all spectator sports.” The fact that Angell, venerable, veteran New Yorker writer and editor, has chosen to illuminate baseball more than hockey in his career is disappointing, but at least he’s a fan. More worrying are those who’ve looked to the ice and felt nothing. Maybe they just haven’t seen enough hockey or haven’t seen the right kind. For all those, like Faulkner, who’ve seen the game and misconstrued, misunderstood, or malspoken it, how many innocents are there who just need a bit of tutoring, as opposed to those we should outright ignore?

Take Pierre de Coubertin, the French founder of the modern Olympics, for instance. This is more of a slight than an outright insult, and a slight slight at that. De Coubertin believed — there’s an entire article he wrote about this in 1909 — that hockey was no more than a means to an end. Hockey had no mental or moral qualities, or if it did, they didn’t matter. The only reason to play hockey was to improve your skating. You know how fencing on horseback makes you a better rider? No, I hadn’t heard that one, either. Same sort of thing, though. Hockey teaches the skater how to start, stop, pirouette, jump. Also boosts your mettle: “The hockey player fears no obstacle and willingly launches himself into the unknown.”

There are those who only see hockey as a scourge to skating. An article in an 1863 edition of a British magazine waxed this way, starting with this ode: “I do believe that skating is the nearest approach to flying of which the human being is as yet capable.” So why ruin it? The hockey here is the massed antique version, fifty or a hundred people chasing a ball over frozen glens and ponds — and wrong, wrong, wrong. It’s unworthy of the true skater’s attention, an illegitimate use of the skate, and worse, the writer says cricket is degraded when it’s played on ice. “I should be truly glad,” he finishes, with a flourish, “to see the police interfere whenever hockey is commenced.”

Put-downs by smart people we thought of as friends stab at the chests of those of us who love the game, if I may speak for the group. Maybe because he himself likes Canadians, the American novelist Richard Ford leaves it to his character Frank Bascombe to call hockey an uninteresting game played by Canadians that’s only redeemed because a sportswriter friend of his can sometimes make it seem more than uninteresting. That stings, especially the fine-tuned implication that Canadians is a sufficient insult all on its own.

It’s not as if we can’t take a joke. We love jokes. We’d just like to be sure that a joke is a joke and not just the kind of slur American writer Roy Blount Jr. perpetrates when he says, “Personally, I love NASCAR about as much as I do hockey. The only thing that would get me to watch a car race on TV would be if they ran over a hockey player every couple of laps.”

Bunny Ahearne always did hate us, so much so that he masterminded the robbery (by confusing rules) of Olympic gold in 1936, plus here was (another) foreigner who never played the game and (also) unless your last name is Larocque, Bunny just isn’t going to fly as a first name. For all those reasons, we can ignore what the vitriolic president of the International Ice Hockey Federation said when we’d beaten the Soviets in 1972. “I don’t think the Canadians will wake up. They’re too small-minded. Now they’ll start to think up alibis.”

Alexander Solzhenitsyn isn’t so easily shrugged off. In The Gulag Archipelago, he poses this question: If you are arrested by the KGB, interrogated in the Lubyanka, pressed to incriminate your friend, what do you talk about instead? Not the latest arrests. Not collective farms.

It is fine if you talked about hockey — that, friends, is in all cases the least troublesome! Or about women, or even about science. Then you can repeat what was said. (Science is not too far removed from hockey, but in our time everything to do with science is classified information and they may get you for a violation of the Decree on Revealing State Secrets.)

In all cases the least troublesome. To have it suggested that hockey doesn’t matter, even if it’s a help to someone under KGB interrogation? That hurts.

Once again comes the fear that there just isn’t enough grist in hockey for writers to mill. We worry that the emperor has no clothes. Or is it what the game reveals about us — its votaries, its guardians, its apologists — that we fear? It’s in our sensitive national nature that when someone criticizes the game that’s ours, we suspect — we fear — that somehow our own tacit decree on revealing state secrets has been violated. It doesn’t even have to be criticism. Sometimes just getting a glimpse of how others size us up can be demoralizing. One short paragraph in German can be enough, if it’s like the one in Karl Adolf Scherer’s history of the International Ice Hockey Federation. It’s in the chapter called “Eishockey Mutterland Kanada,” a seductive phrase in its own right, and one that I defy you not to bark at the next person who walks into the room. Towards the end of the chapter, Scherer confides,

Die Kanadier sind die Erfinder des Körpereinsatzes (Bodycheck), der Strafbank und der allgemeinen Zuchschauer-Auffassassung, daß körperlos spielende Athleten “Drückeberger” sind.

The Canadians were the inventors of the bodycheck, the penalty bench (the “sin bin” or “cooler”) and the widespread view of fans that athletes who shirk bodily contact are “pansies.”

ULF STERNER ENDED up suing hockey. Not hockey, directly. Hockey would not be putting up a defence or paying any damages. In 2008, at the age of sixty-seven, he launched a lawsuit in Sweden against his insurance fund in order to win damages for injuries he’d suffered during his playing career. He said, “I will go all the way to the European Court of Justice, if necessary.” What sounds better is to say that he sued hockey for hurting him so much, which it did; specifically, his spine, ankles, hips, and elbows. At one point he could barely get out of bed in the morning. These were occupational injuries, he told the court when the time came. And the court agreed, awarding him an annuity as compensation.

So hockey hurts. This is easy to say, and it’s even easier to feel. In today’s NHL, you don’t talk about injuries, not out of delicacy but as a matter of operational security. Is it going to aid and abet the New York Rangers if you let on that Carey Price torqued his medial collateral ligament? Maybe not, but safer to call it a Lower Body Injury anyway.

In Finland, hockey used to hurt less. In a study comparing the incidence, type, and mechanisms of hockey injuries in that country from the 1970s through to the 1990s, it was discovered that due to a rise in the rate of “checking and unintentional collision,” contusions and sprains were increasing significantly decade after decade.

Ted Green’s wife noted an odd thing: players seem to be tickled pink when they get injured. “It’s the nature of the beast, I suppose.”

How do you know, in hockey, when you’re hurt? This is a tricky problem. In regular life, the blood and the pain flag it for you, letting you know to stop what you’re doing and summon a doctor. In hockey, not so much: you see blood, you keep going. Feeling fine? That’s when you have to worry. Philadelphia Flyers coach Bill Barber at the start of the 2002 playoffs: “If you’re healthy, if you’re totally bruise-free, maybe you shouldn’t be in the lineup.”

The least of hockey aches would have to be a puck in the skate, bees in the boot. Lace bite sounds benign, but it’s awful, an affliction of dorsal tendons that makes tying your skates extremely painful. Don’t underestimate the hip pointer (höften pekkare in Swedish). Back spasms, I have no doubt, feel worse than they sound.

An unredacted register of injured NHLers from January of 2000 catalogues bruised Dave Reids, fractured Jere Lehtinens, and wonky-kneed Grant Fuhrs. Hamstrung, sore, lacerated, sprained, partially torn, contused, herniated, and compressed, Bob Essensa, Mark Janssens, Derian Hatcher, Antti Aalto, Brian Skrudland, Kirk Maltby, Sean Burke, and Frank Musil waited for their respective hamstrings, backs, calf muscles, ankles, left elbows, chests, thumb ligaments, abdomens, and vertebrae to heal up. Meanwhile, a groin epidemic was sweeping the continent, a contagion linking Dominik Hasek, Jamie Allison, Joe Hulbig, Steve Staios, Jean-Yves Leroux, Peter Popovic, Sean Hill, Grant Marshall, Craig Rivet, and Darren Langdon in a belt-range band of discomfort that they’d probably prefer not to have us dwell on in too much detail.

I DON’T THINK goalposts hated Howie Morenz — there’s no good proof of that. From time to time they hurt him, but you could reasonably argue that in those cases he was as much to blame as they were. Did they go out of their way to attack him? I don’t believe it. What could the goalposts possibly have had against poor old Howie?

Morenz was speedy and didn’t back down and, well, he was Morenz, so other teams paid him a lot of what still gets called attention, the hockey version of which differs from the regular real-life stuff in that it can often be elbow-shaped and/or crafted out of second-growth ash, graphite, or titanium. But whether your name is Morenz or something plainer and hardly adjectived at all, doesn’t matter, the story’s the same: the game is out to get you.

In 1924, his first season as a professional, Morenz developed stiffness against Ottawa, before badly bruising a hip just before he won his first Stanley Cup. In February of 1926, he hurt an ankle in a goalpost crash. A month later, playing Pittsburgh, he had to be carted from the ice after bruising the same ankle in a collision with the Big Train himself, Lionel Conacher.

Morenz went into another post in late 1927. Opening night, Madison Square Garden: fans in fur and finery, the West Point Army Band, New York’s mayor was there to drop the puck between Morenz and the Amerks’ Billy Burch. Early on, Burch banged up a knee in what looked like a serious way while Morenz stayed around long enough to score a pair of goals. The smash-up in the second period does sound like a highway disaster: six players went down in the Canadiens’ net. “Driven against the stout iron support,” Morenz suffered “a severe bruise on his left side and possible kidney injury.”

Hec Kilrea slashed him over the head in Ottawa in 1928, not really but maybe sort of on purpose. Three years later, Boston’s Eddie Shore smote him on the forehead, though it was Shore’s teammate, George Owen, who got the blame and the penalty. With Kilrea, he and Morenz were “exchanging compliments.” Then (from the Ottawa Citizen):

Morenz turned Kilrea around completely with a jab in the mouth, and as the blonde left winger was whirling, his stick caught Morenz over the right temple, inflicting a gash of about two inches.

Four stitches bound the wound; Morenz returned in the third period. Kilrea said he was very sorry; Morenz told reporters Kilrea wasn’t the type to injure a man deliberately. “Bright particular star of the Canadien sextet,” the New York Times was saying a few days later, Morenz was still sporting plasters, “although his brain is said to be functioning fairly well.”

How did he keep going?

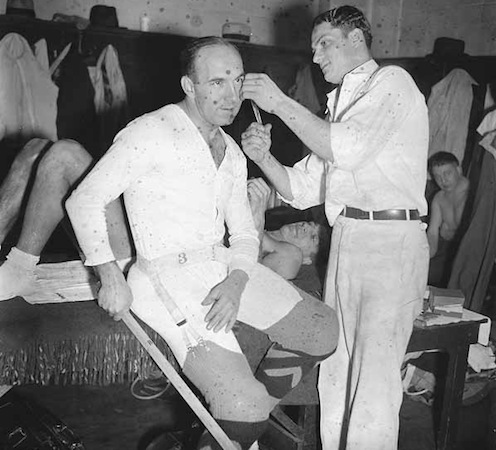

Sew there: Chicago’s Howie Morenz takes stitches in a Boston dressing room in the mid-1930s.

Is it worth noting here that he gave as good as he got? Or, another way of looking at it: playing hockey, you’re at risk not only of getting hurt but of hurting others. For Morenz, this meant:

It was Morenz, too, who broke Clint Benedict’s nose with a shot in 1930, forcing the Maroons goalie out of the game and, a little while later, out of his career. I’m not saying that was Morenz’s fault: the evidence seems to show that Benedict’s nerves were already well crushed. A month later, when he returned, he was wearing the nose-guard that may or may not have been the NHL’s first goalie mask. It looked strange and vexed Benedict’s vision so much that he’s supposed to have discarded it before the game against Ottawa, that March, when someone fell on him. He decided to retire. Possibly another shot of Morenz’s might have caught him in the throat at some point in here, too.

Can we agree, also, that Morenz didn’t necessarily need hockey to hurt himself?

In 1932, he had his mother-in-law staying over at his house in Montreal, 4420 Coolbrook Avenue. Streetview it on Google and you can imagine him standing there on the porch surveying — actually, no, not really. Too many silver Hondas and Kias parked in front, now, all those twenty-first-century strewn garbage bins. It looks like a pleasant street, calm and leafy.

Morenz drove Mrs. Stewart home to her house on Jeanne-Mance, not far, a grey street on the day Google scoped by, with its trees looking spindly. Turn the view around and you can admire the big cross up on Mont-Royal.

Possibly Mrs. Stewart was giving Morenz hockey advice all the way home, stuff he wasn’t hearing anywhere else, and he took it, too, and prospered, and no one ever knew but them. You don’t know. Without a photograph at hand, you’re free to assign her a prim, tweedy, bespectacled look, but is that fair? The door of her house was unlocked when they got there. In they walked. Mrs. Stewart turned on the light and that’s when the tall man stepped out from behind the door with a revolver in hand. He said either “Give me money” or “Give me money before I shoot you.” Accounts vary.

Morenz stayed cool. The season had been over for a month, but he still had his hockey wits about him. He told the guy, careful with that gun. He said, “If you shoot Mrs. S. you’ll be in the hoosegow a long time.” Not those exact words, but close. Did the guy know who it was, threatening him with hypothetical jail sentences? Was he a tall Habs fan? Impossible to say. We do know that Morenz jumped him. Think of that! Little Morenz! He pulled down the guy’s overcoat — smart — partially trussing him. This all has to have been fast and frenzied; newspaper accounts slow it to sludge. The thug, they said. He got an arm free and slashed Morenz “several times over the head and temple.” With a hockey stick no one previously noticed? No: the gun. He added another bash as he shed his coat, then he was gone, running south on Jeanne-Mance, disappearing down Fairmont.

Mrs. Stewart telephoned the police. Special constables Geraldeau and Laroche came immediately. From reading too many Tintin books, I see Morenz sitting on the floor, legs splayed, hand to head, stars and punctuation and musical notes orbiting. He gave the policemen a good description of the suspect: thirty-fiveish, dark suit, grey fedora. They couldn’t figure out how the guy got in. In his abandoned coat they found a flashlight. The cut on Morenz’s head looked bad, but he said he was okay with some first aid. He didn’t go to the hospital.

Also, back in 1928, while Morenz was golfing at Montreal’s Forest Hill course, lightning just missed him. There was a sharp crackle, a flash; the club he’d been about to swing was left twisted and split. Morenz and his caddy both said they felt a jolt.

A SCRAP IS what happens when, in 1973, Norm Dube of the Kansas City Scouts tries to clear Minnesota’s Dennis O’Brien from the front of the net and they tangle, resulting in five-minute majors. Except that O’Brien doesn’t want to let the matter drop, forcing the referee to send him to the dressing room, but instead of going there, O’Brien goes after Dube again. Hockey has lots of different words for fights: fireworks and bouts, spats and imbroglios. It used to have shindigs and tong wars and schemozzles, great words all.

Hockey likes to drape the spectacle of its millionaires wailing fists into one another’s skulls with words that cloak the stupidity, smudge the inanity into harmlessness. Chucking the knuckles sounds kind of fun, like a game at a summer fair. Dropping the mittens. Tilt is a hockey-fight word, and so too are bout and set-to. An argy-bargy is a soccer hoo-ha, as much as it sounds like another name for the Falklands War. A Canadian version might be argle-bargle, which has a hockey air to it; in fact, it’s defined as the sound made by seabirds. We’ve already decided that donnybrook is foreign and obsolete. A scuffle, altercation, melee; or how about brouhaha? The extra-curricular, Craig Simpson sometimes says on Hockey Night in Canada, suggesting chess club or mathletics. Clarence Campbell preferred the respectable Marquis-of-Queensberry formality of fisticuffs. As in: “I have been in hockey forty years,” he said in 1971, “and I can think of only one incident in which a man has been seriously injured in a personal fisticuffs by a punch in the nose.”

In Chicago in 1953, during a disagreement between Black Hawks and Bruins, the attendant manning the door to one of the benches took fright and abandoned his post. The players fell into the Chicago bench area and were rolling about, among them my old History teacher, Mr. Armstrong. That was a rumpus.

A fracas is what happens in Paris, France, on a Sunday in 1933, when a visiting Toronto team loses the game, then gets into a kerfuffle at a restaurant with some locals that sends a defenceman to hospital and the coach, Harold Ballard, to police court.

Dropping the buckets is hockey terminology associated, usually, with an intention to chuck the knuckles.

They’re throwing them from Port Arthur is an admiring phrase you might have heard Don Cherry use to approve a particularly vivid fight. The five reasons to throw, according to one who threw: (1) an opponent ill-treats one of your stars or (2) they abuse your goalie; (3) you want to change the momentum of the game or (4) you’re trying goad the other team into a penalty; or (5) you don’t like someone.

Jokey terms for fighters: head-boppers, pot-stirrers, Bob Gainey’s new windup toy. Players not known for fighting who drop their gloves sometimes come in for gentle ribbing, as in: hey, did you catch the powder puff between Spezza and Markov?

Goon is another funny word, though not necessarily one that the goons themselves like to be called. It does carry big baggage, it’s true, a whole Samsonite’s worth of unflattering definitions: “stupid or oafish person,” for one, derived from gony (“simpleton,” 1850). Or the term applied by sailors to the albatross and similar large, clumsy birds (1839). Or in the sense of “hired thug,” first noted in 1938, probably with a nod to Alice the Goon, a muscle-bound dull-wit in E.C. Segar’s original Popeye comic strip.

You don’t call a goon a goon, because if you do, Bob Probert’s wife might tell you that you don’t know him and you don’t know hockey. Rent-a-goon is no better. Heavyweight? Tough guy? Badman used to be a popular term, in reference to Bad Joe Hall or Sprague Cleghorn, or (in 1956) Lou Fontinato, who was a blockbuster, giving a larruping Ted Lindsay a run for his money in riot-producing badman honours. The list of badmen carries on: Billy Coutu, Eddie Shore, Red Horner. The last of the breed may have been Detroit’s Howie Young. In the early 1960s, the Saturday Evening Post took the measure of the average badman as being “long on muscle and short on Freud.”

Enforcer seems to have entered hockey’s lexicon in or about 1939 without anyone really asking the question, what does the enforcer enforce? Not the rules, given that fighting lies beyond their limits. Policeman is an odd designation, too, though it’s one that Marty McSorley liked “in a romantic sense.” Vigilante is more appropriate given that any policing that’s done on the ice is the work of referees, linesmen, and actual uniformed police officers. Tough guy does have a bit of a musty, Damon Runyon ring to it. Pugilist is mock-archaic. Gladiator? The players who fill these roles are often provided with names that seem strangely appropriate to the job they perform. Does Domi not sound like a curt warning muttered at the boards behind the net? Grimson, Boogaard, Kordic, Kurtenbach, Kocur: they all have the ring of violent threats, of bad outcomes. (Although John Ferguson sounds harmless enough. And Fergie makes him sound as plush as a toy palomino pony.)

Because fighting is such a, quote, shitty job, fighters actually love the game more than anyone else. “They have to,” Kris King has said, “because they’re setting aside part of their dream to do it.”

Hockey-fighting is harder than boxing, said Rod Gilbert. Scoring a goal is easier, according to Rob Ray. You need a strong character to punch and be punched. Big hands are recommended. Ferguson was super-motivated, plus he despised the opposition, plus he studied other fighters to figure out who went for the legs, who backed off, who (looking at you, Carl Brewer) didn’t drop their stick. You can start a fight with a flick of a finger, rub a guy’s elbow, or say a word or two.

The main technical difficulty involves, according to Gilbert and Brad Park, keeping your balance. Nick Metz advised getting up on your toes. Gordie Howe said you hold on to your stick until the other guy drops his. Tie Domi didn’t have a fighting style. Just grab hold, said Tony Twist, throw your fists, see what happens. You have to get the first punch, Lou Fontinato, among others, felt. Although for Dave Schultz, the priority was to get a good grip on the guy’s collar, even if that meant allowing him a couple of first punches. Orland Kurtenbach stood back until you came at him, which is when he got you with his reach, which was tremendous. He stood back, cocked his arm, boomba.

It’s almost like shooting the puck, said Bobby Orr, you want to be getting as much power into your punch as you can. Being a lefty helps, too. Guys have real trouble with lefties.

Wait a minute. Bobby Orr?

Yes, true: he has a helpful section in his how-to book, from 1974, where he shares his secrets. “Some people think fighting is terrible,” he explained to Life in 1970, “but I think the odd scrap — without sticks — is part of the game.”

Don Cherry used to file his fingernails to prepare. He said he was never mad when he fought, ever. Mick Vukota was firmly in the face-plant camp: “You pick the guy up, get the elbow across the head, and slam him into the ice.” Kevin Lowe says that when Dave Semenko fought, he destroyed guys, traumatizing both teams. “Not only was the opposition devastated, we were devastated.”

Keith Magnuson never minded losing a fight. “I really mean this,” he said. Not that he didn’t work at his craft. After his rookie season, he took boxing lessons from former world bantamweight champion Johnny Coulon. That was the year he had a fight a game, serving 291 penalty minutes, or almost five hours in the box.

Bang your hands on the floor while you’re watching TV: Tony Twist learned from a kickboxer that’s how you condition your knuckles. The swelling makes your tendons stronger.

If you’re going to fight, fight. Stand there and give it, and take it — after you get rid of your gloves and stick and take off your helmet, of course. Then, punch. That’s what veteran sportswriter Stan Fischler’s 2008 formula for fixing hockey amounted to: more haymakers! Back to the days of pure and simple punching. If you wrestle or pull the guy’s shirt over his head, waltz around without punching, then sorry, pal, that’s extra penalties for you, because it’s boring.

Some say that the greatest fight ever in the NHL may have been the mutual wailing that Chicago’s Johnny Mariucci and Black Jack Stewart from Detroit laid on one another in the late 1940s. Twenty minutes it’s supposed to have lasted, on the ice and into the penalty box, the most brutal battle Gordie Howe ever saw.

Frightful hockey sounds:

If you saw Todd Bertuzzi skate down Steve Moore in 2004 and punch him in the back of the head — with the result that Moore will never play another NHL game in his life — maybe you heard Ken Dryden say it was like watching a National Geographic special with the lion taking down the antelope.

Pierre Pilote’s dad was an amateur boxer nicknamed Kayo. “The first English words I ever learned were, ‘Do you want to fight?’” Pilote said. “I averaged a fight a week and won my share. I had that animal instinct, you might say.”

John Ferguson’s knuckles always bled. Sometimes, the day after a fight with Stu Grimson, hockey players who suited up again for the next game found that they couldn’t turn left or simply fell down. Defencemen have told doctors that once in every four or five fights, they’d get stung, the sky would change colours, and they’d find themselves in a daze.

The NHL got a new rule in 1977 whereby the “third man” into a fight would be ejected from the game and fined one hundred dollars. That would make the violence more sensible, some said. “You’ll always have fights as long as you have hockey,” Chicago coach Billy Reay reminded the pacifists. Clarence Campbell: “Hockey takes the position that if a man considers himself badly used he may want to punch the offender in the nose. This is certainly preferable to having him strike him with stick or skate.” After three decades at the NHL helm, Campbell gave way that year to John Ziegler. “We’re going to put some attention on fighting at our annual meeting,” the new president said at the beginning of his reign. “But with the cost of players, there just aren’t that many goons around any more.”

In 1999, when Scott Parker’s helmet fell off, Bob Probert threw the hardest punch Scotty Bowman ever saw in hockey, and when Parker went down, Probert told him, “Well, I guess I broke ya.”

That was six years into Gary Bettman’s tenure as NHL commissioner. Fourteen years after that, he was interviewed by the CBC’s Peter Mansbridge, and cautioned, “Before you make a fundamental change and say, okay, we’re changing the rule on fighting — you know, you fight, you’re gone for two weeks — you have to be very careful. It needs to evolve. Because for every action there’s probably an unintended consequence that you weren’t aware of.”

WE KNOW THEIR names now, the doctors of hockey, they’re in the news as much as their patients. Dr. Micky Collins was the concussion specialist who spoke first at Sidney Crosby’s famous state-of-the-skull address in September of 2011. He talked about fog and Ferraris, herding cows back into the barn. He cited deficits and impacts, and introduced us to the word vestibular. Dr. Ted Carrick was there, too, explaining small perturbations and great perturbations. He stayed in the news, having loaded Crosby into a whole-body gyroscope and turned him all around as part of his treatment.

Dr. Joseph Maroon also tended Crosby, and both he and Dr. Collins were advising Philadelphia’s Chris Pronger that same week to park his shaken brain for the rest of the season. It was Toronto neurosurgeon Dr. Michael Cusimano who said (the same week) that the NHL wasn’t doing enough to protect its players. Earlier that fall, he and Dr. Paul Echlin from London, Ontario, had unveiled a study of two Junior teams that found that 25 per cent of the players had suffered concussions.