In July 2013, the think tank The Center for American Progress released a study it had commissioned from the Worker Rights Consortium that tracked global shifts in garment worker wages over a ten-year period, from 2001–2011. “Global Wage Trends for Apparel Workers, 2001–2011” focuses on top exporters to the United States and found that in most cases, wages relative to buying power decreased for top apparel exporters to the U.S. including dramatic downward shifts in Mexico and Bangladesh. A portion of the report is reprinted here. To download the full report including methodology, visit www.americanprogress.org/issues/labor/view.

When images of poor labor conditions in the garment industries of leading apparel-exporting countries reach the global news media, it is often because those conditions seem uniquely and unjustifiably extreme. Malnourished workers working fourteen-hour days faint by the hundreds in Cambodian garment plants.1 Hundreds more are killed in deadly factory fires in Bangladesh and Pakistan by owners who lock exit doors when fires start—presumably because they fear that fleeing workers will stop to steal clothes.2

Yet these images reflect a common basic reality: garment workers in many of the leading apparel-exporting countries earn little more than subsistence wages for the long hours of labor that they perform. And in many of these countries, as this report discusses, the buying power of these wages is going down, not up.

Critics of anti-sweatshop advocates often argue that concern over poor labor conditions in apparel-exporting countries is misplaced and counterproductive.3 According to their argument, jobs in garment factories, no matter how low the wages or how difficult the conditions, benefit low-skilled workers because they provide better conditions and compensation than jobs in the informal and agricultural sectors of developing countries. Moreover, they posit, export-apparel manufacturing offers these workers—and, by extension, developing countries—a “route out of poverty” through the expansion of the manufacturing sector.4

The first part of this argument is largely noncontroversial. Employment in the urban formal economy typically offers better and steadier income than informal-sector work or agricultural labor. Yet self-labeled “pro-sweatshop” pundits have not explained why the price that workers in developing countries have to pay for steady wage employment should be grueling working conditions, violations of local laws and basic human rights, and abusive treatment, except to say that there are always some workers for whom labor under any conditions will be an improvement over the status quo.

The second part of the argument, however—that employment in export-garment manufacturing offers a “route out of poverty”—rests on either an extremely low benchmark for poverty5 or the promise that such work offers the future prospect of wages that actually do support a decent standard of living for workers and their families—that is, a “living wage.”6 In other words, for the export-garment sector to actually offer workers in developing countries a “route out of poverty,” either these workers’ current living conditions must not amount to poverty or, if they do, these workers must be able to expect to escape poverty in the future with the industry’s further development.

Over the past decade, however, apparel manufacturing in most leading garment-exporting nations has delivered diminishing returns for its workers. Research conducted for this study on fifteen of the world’s leading apparel-exporting countries found that between 2001 and 2011, wages for garment workers in the majority of these countries fell in real terms.7

As a result, we found that the gap between prevailing wages—the wages paid in general to an average worker—and living wages8 for garment workers in these countries has only widened. A comparison of prevailing wages to the local cost of a minimally decent standard of living for an average-sized family finds that garment workers still typically earn only a fraction of what constitutes a living wage—just as they did more than ten years ago. While these workers may not live in absolute poverty, they live on incomes that do not provide them and their families with adequate nutrition, decent housing, and the other minimum necessities of a humane and dignified existence.

To summarize briefly:

• We studied nine of the top ten countries in terms of apparel exports to the United States as of 2012 and fifteen out of the top twenty-one countries by this same measure. We only studied fifteen out of the top twenty-one countries because we were limited to those places in which we had regular field-research operations at the time of the study.9 On average, prevailing straight-time wages—pay before tax deductions and excluding extra pay for overtime work10—in the export-apparel sectors of these countries provided barely more than a third—36.8 percent—of the income necessary to provide a living wage.

• Among the top four apparel exporters to the United States, prevailing wages in 2011 for garment workers in China, Vietnam, and Indonesia provided 36 percent, 22 percent, and 29 percent of a living wage, respectively. But in Bangladesh, home to the world’s fastest-growing export-apparel industry, prevailing wages gave workers only 14 percent of a living wage.

• Wage trends for garment workers in six additional countries among the top twenty-one countries11 were also studied in terms of apparel exports to the United States. In four of the six countries—the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, the Philippines, and Thailand—prevailing wages also fell in real terms by a per-country average of 12.4 percent, causing the gap between workers’ wages and a living wage to widen in these countries as well.

• Garment workers in Mexico, the Dominican Republic, and Cambodia saw the largest erosion in wages. Between 2001 and 2011, wages in these countries fell in real terms by 28.9 percent, 23.74 percent, and 19.2 percent, respectively.

• In five of the top ten apparel-exporting countries to the United States—Bangladesh, Mexico, Honduras, Cambodia, and El Salvador—wages for garment workers declined in real terms between 2001 and 2011 by an average of 14.6 percent on a per country basis. This means that the gap between prevailing wages and living wages actually grew.

• Real wages rose during the same period in the four remaining countries among the top ten exporters that we studied—China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam—as well as in Peru and Haiti, which were among the top twenty-one countries. Wage gains in India and Peru, however, were quite modest in real terms at 13 percent and 17.1 percent, respectively, amounting to less than a 2 percent annual gain between 2001 and 2011. Wages rose more substantially in real terms in Haiti (48.2 percent), Indonesia (38.4 percent), and Vietnam (39.7 percent) over the ten-year period. Even if these rates of wage growth were sustained in these three countries, however, it would take on average more than forty years until workers achieved a living wage. Only in China, where wages rose in real terms by 124 percent over the same period, were workers on track to close the gap between their prevailing wages and a living wage within the current decade. According to our research, Chinese apparel workers are on course to attain a living wage by 2023, but only if the rate of wage growth seen between 2001 and 2011 is sustained.

The prevalence of declining wages and persistent poverty for garment workers in a majority of the world’s leading apparel-exporting countries raises doubt that export-led development strategies create a rising tide that lifts all boats in most countries pursuing these strategies.

As noted, this report examines actual trends in real wages and other related indicators between 2001 and 2011 for garment workers in fifteen of the top twenty-one countries exporting apparel to the United States. It examines whether and where prevailing straight-time wages for garment workers are actually going up or down in terms of buying power—that is, whether workers are en route out of poverty, stuck in it, or headed deeper into it. As the report discusses, the prevailing straight-time wage rate for most garment workers in most of the countries examined was the applicable minimum legal wage in their respective countries. This is due to several factors, including the widespread practice of governments setting industry- and even job-specific minimum wages, and, in many cases, a lack of worker bargaining power due to limited alternatives for formal-sector employment and low unionization rates.

The report compares levels of prevailing wages in 2001 and 2011 to the level of earnings that workers and their families need in order to afford the basic necessities of a non-poverty standard of living—a living wage—and whether garment workers are actually on a path to reach this goal or whether they are falling further behind. Our research shows that only a handful of the countries examined have achieved even modest growth in real wages over the past decade, and in only one, China, was the rate of growth significant enough that the country’s workers would achieve a living wage in the relatively near term if it were to be maintained. In all of the other countries, there has either been negative real-wage growth or growth that is so slow that a living wage is decades away. Unsurprisingly, growth in real wages for garment workers tended to be most associated with those few countries that have instituted major increases in their legal minimum wages as a means of poverty alleviation and/or avoidance of social unrest and that in most cases also experienced growth in other higher value-added manufacturing sectors, not just garment production.

In sum, our research indicates that while the establishment of an export-garment-manufacturing sector may tend to expand formal employment that is more profitable than alternatives in the informal sector or agricultural labor, the growth of an export-apparel industry does not necessarily raise its workers out of poverty when left to its own workings. While the expansion of garment-sector employment may have made the very poor initially significantly less poor, it has offered limited opportunities for workers in most of the major apparel-exporting countries to make further upward progress toward an income that offers them a minimally decent and secure standard of living.

Instead, in most of the leading apparel-exporting countries, the wages for garment workers have stagnated or declined over the past decade. Wages have only risen significantly in real terms in countries whose governments have taken affirmative steps to ensure that workers share the rewards from the industry’s growth and whose manufacturing sectors have diversified to put apparel factories in competition for labor with makers of higher value-added goods.

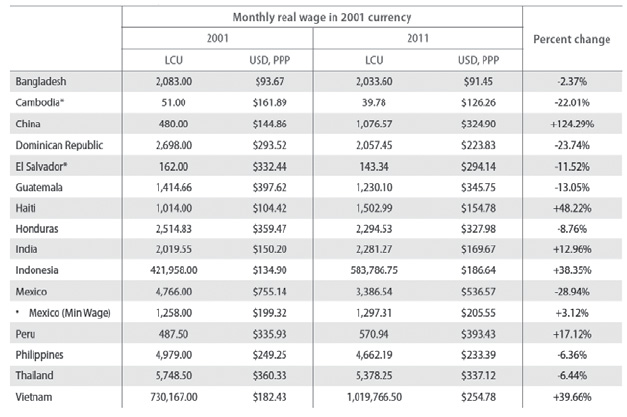

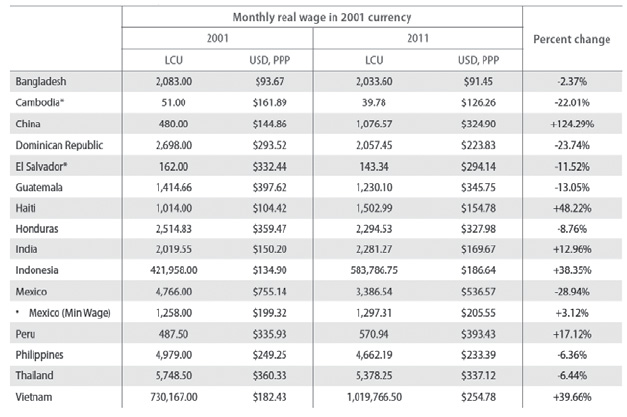

REAL WAGE TRENDS FOR GARMENT WORKERS, 2001–2011

Using the methodology discussed in the appendix, we estimated prevailing straight-time wages for garment workers in nine of the top ten and fifteen of the top twenty-one countries exporting apparel to the United States in 2001 and 2011. To observe trends in the real value of workers’ wages during the intervening period, we deflated our estimate of the prevailing wage in 2011 for each country by the aggregate consumer price inflation that a country had experienced from 2001 to 2011.12 By this measure, real wages for garment workers in nine of the fifteen countries included in this study fell over that time period.

The garment exports of the fifteen countries studied comprised nearly 80 percent of all apparel imports to the United States in 2011.13 Prevailing straight-time wages for garment workers fell in real terms in five out of the seven countries studied in the Americas and four out of eight of the countries studied in Asia. The remaining six countries where wages increased, however, produce the majority of garments that are exported to the United States.14

WHERE REAL WAGES FELL IN NINE OF THE TOP TEN APPAREL EXPORTERS: BANGLADESH, MEXICO, HONDURAS, CAMBODIA, AND EL SALVADOR

In the nine countries we studied among the top ten apparel exporters to the United States,15 wages for garment workers in five countries—Bangladesh, Mexico, Honduras, Cambodia, and El Salvador—declined in real terms during the period from 2001 to 2011 by an average of 14.6 percent on a per-country basis. These countries shipped nearly 20 percent of the total value of garments exported to the United States in 2011.16

Mexico registered the largest decline, seeing a 28.9 percent drop in workers’ buying power over this ten-year period. This decline coincided with a much larger one in the country’s market share, as the country fell from the United States’s top source of imported apparel in 2001, when it accounted for nearly 15 percent of imports, to the United States’ fifth-largest clothing supplier in 2011, when it had a market share of slightly less than 5 percent.17

Bangladesh and Cambodia, the fourth- and eighth-largest clothing exporters to the United States in 2001, respectively, dramatically expanded their apparel exports to the United States during this period, recording increases in both countries of roughly 18 percent in the value of their shipments between 2010 and 2011 alone.18 Since 2011 Bangladesh has overtaken Indonesia and Vietnam to become the second-largest exporter of apparel to the United States.19

Both Bangladesh and Cambodia, however, saw wages fall in real terms between 2001 and 2011. The decline in Bangladesh—2.37 percent over the decade as a whole—was substantially moderated by a significant increase in the minimum wage, which was instituted in 2010.20 In Cambodia, however, the loss of buying power for workers was much more significant at 19.1 percent, particularly as the country’s export-apparel industry was under the oversight of the International Labour Organization’s Better Factories Cambodia program during the entire period.21 In 2011 Cambodia and Bangladesh had the lowest prevailing monthly wages for straight-time work of any major apparel exporter to the United States at approximately $70 and $50, respectively.

The two leading Central American exporters, Honduras and El Salvador, where labor costs are considerably higher, both saw real wages for apparel workers fall. Wages for garment workers declined in Honduras in real terms by 8.76 percent from 2001 to 2011, as the country’s rank among major apparel exporters to the United States fell from fifth place to seventh place during the same period.22 Prevailing monthly straight-time wages for Honduran garment workers in 2011 stood at $245.71.

El Salvador, which failed to rank among the top ten apparel exporters to the United States throughout the first part of the decade, stood as the ninth-largest exporter in 2011.23 Straight-time wages for its apparel workers, however, fell by slightly more than 11.5 percent during this time, to a monthly figure of $210.93.

WHERE REAL WAGES GREW: CHINA, INDIA, INDONESIA, AND VIETNAM

In the four remaining countries among the top ten exporters that were studied—China, India, Indonesia, and Vietnam—prevailing real wages for garment workers rose by an average of 55.2 percent, or slightly less than 6 percent per year between 2001 and 2011. These four countries collectively made up 57 percent of clothing imports to the United States in 2011, and all four recorded gains in market share during this period.24

Wage gains for garment workers in India between 2001 and 2011, however, were much more modest than in the other three countries at 13 percent, averaging only 1.3 percent per year in real terms, despite the fact that in 2011 the country stood as the sixth-largest garment exporter to the United States with its 7.23 percent market share, up from 3.2 percent in 2004.25 Prevailing straight-time wages for Indian garment workers were $94 per month in 2011.

The buying power of workers’ straight-time wages rose more substantially over this period in Indonesia and Vietnam, the third- and second-largest apparel exporters to the United States in 2011, respectively. Indonesia saw an increase of 28.4 percent, and Vietnam saw an increase of 39.7 percent. The two countries also saw their market shares increase to 6.48 percent from 3.4 percent and to 8.53 percent from 4 percent, respectively, between 2004 and 2011.26 In the case of Vietnam, however, this figure reflects a significant minimum-wage hike that did not take effect until October 2011.27 Even with these gains, however, prevailing straight-time wages for garment workers in Indonesia and Vietnam stood at only roughly $142 and $111, respectively, per month in 2011.

Wage gains for garment workers during this period were greatest in China, where wages more than doubled in real terms by 129.4 percent. Apparel imports from China rose dramatically from 2001 to 2011, a period in which China overtook Mexico as the leading exporter of garments to the United States and more than tripled its market share, from 10.2 percent in 2000 to nearly 38 percent in 2011.28

REAL WAGE TRENDS AMONG OTHER TOP APPAREL EXPORTERS TO THE UNITED STATES

Wage trends for garment workers in six additional countries that were among the top twenty-one countries29 in terms of apparel exports to the United States were also studied. In four of these countries—the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, the Philippines, and Thailand—wages also fell in real terms from 2001 to 2011, by a per-country average of 12.4 percent. In the other two countries, Haiti and Peru, wages rose in real terms over the same period, by 48.2 percent and 17.1 percent, respectively.

WHERE REAL WAGES FELL IN REMAINING TOP FIFTEEN APPAREL EXPORTERS: DOMINICAN REPUBLIC, GUATEMALA, THE PHILIPPINES, AND THAILAND

Among the countries in the group where wages fell, the Dominican Republic saw the largest decline. Its workers’ straight-time pay fell by 23.74 percent during this time period. This period also saw an equally dramatic decline in the standing of the Dominican garment industry in comparison with those of other major apparel-exporting countries. While the Dominican Republic was fifth among the top garment exporters to the United States in 2000, it had fallen to 21st by 2011, having lost 80 percent of its market share over the intervening decade.30

As with all but one of the countries in the Caribbean Basin that were included in this study, wages for garment workers in Guatemala fell during this period, by just more than 13 percent. Guatemala also lost a significant portion of its share of U.S. apparel imports during the past decade, with its market share declining from 3 percent in 2004 to 1.7 percent in 2011.31

Two other apparel-exporting countries that were studied, the Philippines and Thailand, also saw straight-time wages for apparel workers fall slightly during this period, by just more than 6 percent. These countries each also lost roughly half their share of U.S. apparel imports during the decade, with their market share declining from roughly 3 percent each in the first half of the 2000s to approximately 1.5 percent each in 2011.32

WHERE REAL WAGES GREW IN REMAINING TOP FIFTEEN APPAREL EXPORTERS: HAITI AND PERU

Wages grew in real terms in two other countries in the Americas that were included in this study, Haiti and Peru. In 2011 these two countries represented the 19th- and 18th-largest exporters of apparel to the United States, respectively.33 Wage growth for Haiti’s garment workers was nearly 49 percent, much more robust than the 17 percent wage growth that Peru’s workers experienced over the same period. The growth in Haiti was significantly related to substantial increases in the Haitian minimum wage that were fiercely opposed by that country’s apparel industry.34

Yet even after the significant minimum-wage increase was implemented in 2009, Haitian apparel exports to the United States continued to rise sharply, by more than 40 percent from 2010 to 2011, compared to an 8 percent increase in Peru’s apparel exports to the United States during the same period.35 In 2011 straight-time wages for garment workers in Haiti, at $131 per month, were roughly half those earned by workers in Peru, who earned $263 per month.

MONTHLY REAL WAGES IN FIFTEEN OF THE TOP TWENTY-ONE APPAREL EXPORTERS TO THE UNITED STATES, IN 2001 CURRENCY36

COMPARISONS OF PREVAILING WAGES TO LIVING WAGES

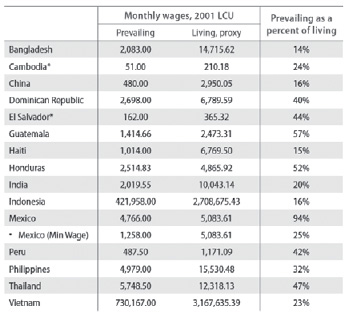

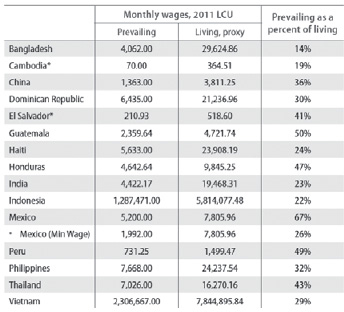

In this section, we compare our estimates of prevailing straight-time wages in the garment industries of the leading apparel-exporting countries—known as prevailing wages—with estimates of the income that is needed to ensure that a worker and his or her family can afford the basic elements of an adequate standard of living—known as a living wage. For each country included in this study, we compare prevailing wages to living wages in both 2001 and 2011.

These comparisons reveal that in most major garment-exporting countries, as prevailing wages declined in real-wage levels, the already large gap between prevailing wages and living wages only grew between 2001 and 2011. Moreover, as we discuss below, with the noteworthy exception of China, the gap between prevailing wages and living wages is still significant in the countries where prevailing wages have risen in real terms, and this is unlikely to be overcome within the next twenty to thirty years.

DEFINING A LIVING WAGE

The right of workers to earn a living wage and the obligation of business enterprises and governments to ensure its provision are enshrined in the basic instruments through which the international community has articulated basic human rights and the rights of labor.37 Contrary to assertions sometimes made by multinational corporations seeking to avoid this responsibility,38 there is a broad consensus on the elements of a living wage, at least as far as the types of costs that it should cover and the best practices for its calculation.39

A recent study on estimating living wages, conducted for the International Labour Organization, or ILO, by Richard Anker, a former senior economist with that organization, describes a living wage as one that permits “[a] basic, but decent, life style that is considered acceptable by society at its current level of economic development … [such that] [w]orkers and their families [are] able to live above the poverty level, and … participate in social and cultural life” (emphasis added).40

The ILO living-wage report notes that it is well-accepted that a living wage must provide for the basic needs of not only the individual wage earner but also for his or her family.41Anker points out that leading nongovernmental organizations, or NGOs, that have considered the issue, including at least one whose members include many major apparel brands and retailers, are consistent in their belief that a living wage should be attainable in a regular workweek without requiring overtime work.42

Finally, the ILO report addresses the criticism made by some apparel firms that the process of estimating a living wage is arbitrary and/or subjective. Anker observes that, in reality, all existing measures of labor welfare are significantly based on subjective judgments, including national governments’ own minimum-wage laws and their statistical estimates of unemployment.43 The report also makes clear that there is general consensus among entities that promote payment of a living wage on the set of expenses that a living wage should cover, even though there are distinct differences in the methodologies that have been adopted in order to measure these costs.44

METHODOLOGY FOR ESTIMATING A LIVING WAGE IN ONE COUNTRY

To our knowledge, only one apparel factory in a developing country—the Alta Gracia factory in the Dominican Republic—has been certified as actually paying a living wage as defined using the methodological approach that the aforementioned ILO report identified to be the preferred method of making such an estimate.45 The Worker Rights Consortium, or WRC, has verified that this factory’s wages meet a living-wage standard as established through a local market-basket study last conducted by the WRC in 2010 and adjusted thereafter for inflation on an annual basis. (see box below).46

The WRC’s market-basket study avoided a number of methodological flaws that the ILO report identified in a number of other living-wage studies conducted by other organizations in other countries.47 Moreover, the living-wage figure that the WRC arrived at in the Dominican Republic fell roughly at a midpoint between cost-of-living estimates published by the country’s central bank on the one hand and its leading labor federations on the other, suggesting that it may have succeeded in avoiding potential subjective biases.48

Finally, and most significantly, real world evidence at the Alta Gracia factory, including studies currently underway by public health scholars from Harvard University and the University of California, Berkeley,49 indicate that the wage paid at the factory provides at a minimum level—neither particularly generously nor inadequately—for the basic needs of a garment worker and his or her family. The WRC has concluded, based on its original market-basket study and its ongoing monitoring of the factory since 2010, that wages paid at the Alta Gracia factory accurately reflect a minimum living wage for a Dominican garment worker residing in the area where the factory is located and his or her family.50

METHODOLOGY FOR ESTIMATING LIVING WAGES TRANSNATIONALLY

To estimate living-wage figures for 2001 and 2011 for the countries included in the study, we first adjusted our 2008 living-wage figure for the Dominican Republic for inflation using consumer-price-inflation data from the World Bank51 to arrive at living-wage figures for that country for 2001 and 2011. Next, we converted this figure using purchasing power parity, or PPP conversion factors for the other countries for the same years from the World Bank’s International Comparison Project52 to arrive at figures for each country of amounts—in their respective local currencies—that provided the same buying power as the inflation-adjusted living-wage figure for the Dominican Republic.

As a general methodology for estimating living wages transnationally, relying on PPP conversions is admittedly an imperfect approach. It should be noted, however, that this is the method used by the one major multinational corporation to actually implement a living-wage policy in its global operations: the Swiss pharmaceutical firm Novartis International, AG.53 Of particular relevance here, Anker’s 2011 report for the ILO notes that this approach fails to account for variances among countries in the shares of household incomes devoted to different categories of expenditures, such as those on food, housing, utilities, and health care.54

For this reason, the WRC’s longstanding practice has been to conduct market-basket living-wage studies in individual countries in consultation with local informants and researchers in order to arrive at living-wage figures that accurately reflect local expenditure patterns.55 Conducting such individual studies in each of the countries included in this study, however, was beyond the scope of the research conducted for this report, which focused on the actual prevailing wages paid to garment workers during the period under study.

In this case, we determined that the value of our 2008 living wage for the Dominican Republic—as the sole living-wage figure that has been calculated using the preferred market-basket methodology and tested for real-world accuracy through implementation at an export-apparel factory in a developing country—made it a useful baseline for estimating living-wage figures for workers in the export-apparel sectors of other developing countries. Recognizing the limitations of this approach, however, we present these estimates only for the purpose of the current report and remain convinced that actual implementation of a living wage in an individual country requires a locally conducted market-basket study.

PREVAILING WAGES COMPARED TO LIVING WAGES

We estimated a living wage for each of the countries included in this study for the years 2001 and 2011 by using World Bank PPP conversion factors56 to extrapolate from the living-wage figure already in use by the WRC in the Dominican Republic. We then adjusted each of these for inflation. We then compared the 2001 and 2011 living-wage figures to the figures for prevailing monthly wages for garment workers for straight-time work in each of these countries for 2001 and 2011. We then used these comparisons to calculate ratios of the current prevailing wage to the current living wage in each of these countries in both 2001 and 2011. Using these ratios, we then calculated the annual rate of convergence or divergence of the prevailing wage and living wage in each country over the intervening ten-year period. Finally, for those countries where the prevailing wage and the living wage had converged to any extent from 2001 to 2011—that is, in any countries where the gap between the prevailing wage and the living wage in percentage terms had shrunk between 2001 and 2011—we used the rate of annual convergence to calculate the number of additional years required, assuming continued convergence at the same rate, until the prevailing wage equals the living wage.

PREVAILING WAGES CURRENTLY AVERAGE A THIRD OF A LIVING WAGE

In none of the fifteen countries included in the study did the prevailing monthly straight-time wage provide garment workers with the equivalent of a minimum living wage. On average, the prevailing wage in 2011 for garment workers in each of the countries included in the study provided little more than a third—36.8 percent—of the estimated living wage in the same country, as calculated using the methodology described above.

This result is generally consistent with the WRC’s prior research estimating living wages in individual countries based on local market-basket studies, which has found that achieving a living wage typically requires tripling the prevailing-wage rate for garment workers.57 Prevailing wages for garment workers stood in relation to a living wage in essentially the same place that they had ten years earlier, when the average share of a living wage provided by each country’s prevailing wage for garment workers was 35.7 percent.

PREVAILING WAGES COMPARED TO LIVING WAGES IN FIFTEEN OF THE TOP TWENTY-ONE APPAREL EXPORTERS TO THE UNITED STATES, 2001 AND 2011

Not surprisingly, the country where the disparity between prevailing wages and a living wage was greatest was Bangladesh, where prevailing wages for garment workers in 2011—which were lower than those in any other country in the study—provided only one-seventh—14 percent—of a living wage. Also unsurprisingly, since real-wage levels for garment workers remained largely flat in Bangladesh from 2001 to 2011—registering, overall, a decline of 2.37 percent—the disparity between the prevailing wage and a living wage was the same in percentage terms in both 2001 and 2011.

The country where the gap between the prevailing-wage figure and the estimated living wage was the smallest was Mexico, where the prevailing wage in 2011 provided roughly two-thirds, or 67 percent, of a living wage. The narrowness of this gap, however, is largely explained by the fact the Mexico is the one country where the prevailing-wage figure used in this report includes overtime compensation. If one were to substitute as the prevailing-wage figure the legal minimum wage payable in the country’s leading center of garment production, the prevailing wage would supply only 26 percent of a living wage.

Among the other countries included in the study, Guatemala, Honduras, and Peru had prevailing wages in 2011 that provided the largest proportion of a living wage—50 percent, 47 percent, and 49 percent, respectively. Unfortunately, in Guatemala and Honduras, the gap between prevailing wages and living wages actually grew slightly from 2001 to 2011 instead of narrowing.

Excluding Mexico, countries in the Americas had prevailing wages for garment workers that on average equaled 40 percent of the living wage for the same country. The gap was wider in Asia, where prevailing wages for each country provided on average 27.3 percent of a living wage. The country in that region with the smallest gap was Thailand, where prevailing wages provided 43 percent of a living wage. Again, however, this gap was slightly broader in 2011 than it was in 2001.

FUTURE TRENDS IN PREVAILING WAGES VERSUS LIVING WAGES

As would be expected, the only countries where the gap between prevailing wages and living wages narrowed between 2001 and 2011 were those countries where prevailing wages for garment workers had risen in real terms: China, Vietnam, Indonesia, India, Haiti, and Peru. Among these countries, only China saw prevailing wages make substantial gains in closing this gap, more than doubling as a proportion of the living wage—from 16 percent to 36 percent—during these ten years. In the other countries where wages for garment workers rose in real terms, such gains were more modest, representing on average an increase of 31 percent in the percentage share of the country’s living wage that the prevailing wage provided.

We found that even if each of these countries maintains a rate of wage growth for garment workers comparable to that which it recorded between 2001 and 2011, attaining a living wage is still a distant prospect. This is particularly true of India, where it would take—assuming an equivalent rate of real-wage growth going forward—more than a century for workers to reach a living wage, given that prevailing wages rose in real terms from 2001 to 2011 at an annual rate of just 1.3 percent, and that the prevailing wage at the end of this period provided just 23 percent of a living wage. The situation is similar but less extreme in Peru, where despite the fact that the prevailing wage in 2001 already provided a much larger proportion of a living wage at 42 percent, a fairly modest rate of real-wage growth—1.7 percent annually from 2001 and 2011—meant that, at the same rate, the country’s garment workers would not achieve a living wage for more than four decades.

Even in the cases of Indonesia, Vietnam, and Haiti, where wage rates for garment workers achieved significantly greater growth over this period—overall increases in real terms of 38 percent, 40 percent, and 48 percent, respectively, between 2001 and 2011—several decades of further growth at the same rates would be required before workers reached a living wage: 42 years for Haiti, 46 years for Indonesia, and 37 years for Vietnam. Only in China, where wage rates for garment workers have grown at a rate of 130 percent, which far surpasses the rates seen in any of the other countries included in the study, are wage rates projected to equal a living wage within the decade, assuming continued real-wage growth at the same rate. If China does manage to see such growth in real wages for its garment workers over the remainder of this decade—a possibility that seems significantly less than certain—Chinese garment workers will achieve a living wage in 2019.

CONCLUSION

We have examined the trends from 2001 to 2011 in real wages for apparel-sector workers in fifteen of the top twenty-one manufacturing countries. In nine countries—Bangladesh, Cambodia, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, the Philippines, and Thailand—the prevailing real wage for apparel-sector workers in 2011 was less than it was in 2001. That is, apparel-sector workers in the majority of the countries studied saw their purchasing power decrease and slipped further away from receiving a living wage.

In the six countries examined in which real wages increased from 2001 to 2011, wage growth in two of the countries, Peru and India, was modest—less than 2 percent per year. While wage gains for workers in Indonesia, Vietnam, and Haiti were more substantial, it would take an average of more than 40 years for the prevailing wage rate to equal a living wage even if this rate of wage growth were sustained. Only in China did real wages for apparel-sector workers increase at a rate that would lift workers to the point of receiving a living wage within the next decade. Not surprisingly, then, the industrial centers in China where workers benefited from these gains have already seen a loss of apparel production, as manufacturers have shifted their facilities, and buyers have shifted their orders, to lower-wage areas both within China and in other countries.

One key reason that the prevailing wage increased in China is that the government substantially increased the mandated minimum wage, in part in order to limit worker unrest. Because minimum wages in most of the countries studied are both sector and job specific, this points to one possible way forward for increasing workers’ compensation. Countries need to look at increasing minimum wages to help lift workers toward a living wage. Promoting greater respect for the rights of union organization and collective bargaining to empower workers to negotiate wage increases on their own could also have a similar effect.

Doing so would provide greater dignity for workers while helping to build the foundation for a strong, consumer-driven economy. But as the experience of other countries shows—particularly the higher-wage countries in Latin America that saw declines in real wages for garment workers during the last decade—such gains will only be sustainable if manufacturers and buyers are willing to absorb the added labor costs, rather than applying downward price pressure through the threat of exit.

By doing so, these manufacturers, brands, and retailers could help make apparel jobs a true route out of poverty. Raising the prevailing-wage rate for apparel-sector workers is both good for workers and good for economies. It would spark a virtuous circle in which higher wages beget increased demand and thus more and better jobs.

1 Patrick Winn, “Cambodia: garment workers making US brands stitch ‘til they faint,” GlobalPost, October 5, 2012.

2 Farid Hossain, “Fire Exits Locked at Burned Factory,” USA Today, January 27, 2013; and Declan Walsh and Steven Greenhouse, “Certified Safe, a Factory in Karachi Still Quickly Burned,” New York Times, December 7, 2012.

3 See, for example, Nicholas Kristof, “Where Sweatshops Are a Dream,” New York Times, January 15, 2009.

4 Ibid.

5 See, for example, Gladys Lopez Acevedo and Raymond Robertson, eds., Sewing Success?: Employment, Wages and Poverty Following the End of the Multi-Fibre Arrangement, vol. 12 (Washington: The World Bank, 2012).

6 The concept of a living wage and how it can be measured in a given country is discussed at some length in this report. For an in-depth examination of the methodological and policy issues involved in arriving at such an estimate, see Richard Anker, “Estimating a Living Wage: A Methodological Review” (Geneva, Switzerland: International Labour Organization, 2011).

7 As discussed, the WRC measured change in real wages in each country by estimating monthly straight-time wages for garment workers in 2001 and 2011 in local currency and then deflating the 2011 wage figure by the aggregate consumer price inflation in that country during the intervening period, using inflation data from the World Bank. See World Bank, “Data: Consumer price index (2005).”

8 As discussed, the WRC estimated living wages in 2001 and 2011 for each country included in this report by adjusting for inflation the figure it has calculated to be the living wage for the Dominican Republic—which was derived using a market-basket research study and which has been tested through actual implementation—and converting this inflation-adjusted figure into the local currencies of the other countries using the PPP factors developed by the World Bank’s International Comparison Project.

9 For a list of the top countries exporting apparel to the United States, see Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category (U.S. Department of Commerce, 2012).

10 The term “straight-time wages” is used throughout the report to refer to “total earnings before payroll deductions, excluding premium pay for overtime and for work on weekends and holidays, [and] shift differentials.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Glossary (U.S. Department of Labor).

11 For similar reasons to those stated above, the remaining five countries—Sri Lanka, Nicaragua, Italy, Egypt, and Jordan—among the top twenty apparel exporters were not included in the study. Neither was Pakistan. See Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category.

12 World Bank, “Data: Consumer price index.”

13 Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category.

14 Ibid.

15 For reasons previously discussed, the remaining country among the top ten apparel exporters, Pakistan, was not included.

16 Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 Bettina Wassener, “In an Unlikely Corner of Asia, Strong Promise of Growth,” New York Times, April 24, 2012.

20 BBC News, “Bangladesh increases garment workers’ minimum wage,” July 27, 2010.

21 Stanford Law School International Human Rights and Dispute Resolution Clinic and the Worker Rights Consortium, “Monitoring in the Dark: An Evaluation of the ILO’s Better Factories Cambodia Program” (2013).

22 Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ministry of Justice, “Increase the Minimum Wage for Businesses,” August 9, 2011.

28 Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category.

29 As discussed, the remaining six countries among the top twenty-one apparel exporters were not included in this study. See Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category; Steven Greenhouse, “Factory Defies Sweatshop Label, But Can It Thrive?” New York Times, July 17, 2010.

30 Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category.

31 Ibid.

32 Ibid.

33 Ibid.

34 Dan Coughlin and Jean Ives, “Wikileaks Haiti: Let Them Live on $3 a Day,” The Nation, June 1, 2011.

35 Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category.

36 In this table, LCU refers to local currency units, or the average wage calculated for garment workers in the currency of their own country or region. PPP refers to purchasing power parity, or average wages adjusted for the relative cost of common goods and services. For example, in the first row, an average wage in 2001 in Bangladesh is calculated at 2,083 taka, which would be the equivalent of just over US$20 at the conversion rate of the time, but equal to an estimated US$93.67 based on cost of living calculations.

37 See, for example, United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948), Art. 23; ILO, “Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy” (2006). For a discussion of ILO and other international instruments that reference living wages, see Anker, “Estimating a Living Wage: A Methodological Review,” pp. 2–4.

38 See Anker, “Estimating a Living Wage: A Methodological Review,” p. 1. He quotes a 2006 statement from Nike, Inc. that says, “We do not endorse artificial wage targets or increases based on arbitrary living wage definitions.”

39 Ibid. at 25, 49–50.

40 Ibid. at 5.

41 Ibid. at 49.

42 Ibid. at 50.

43 Ibid. at 11–12.

44 Ibid. at 49–53.

45 Compare ibid. at 27—discussing practice of calculating costs for separate categories including food, housing, transportation, clothing/footwear, childcare, and other expenditures—to WRC, “Living Wage Analysis for the Dominican Republic” (2010).

46 Ibid.

47 Compare ibid. to “Estimating a Living Wage: A Methodological Review,” pp. 38–40, which criticizes some living-wage studies for failing to separate categories of nonfood expenditure and failing to provide specific information regarding selection, type, price, and quantity of food items.

48 WRC, “Living Wage Analysis for the Dominican Republic,” p. 8.

49 John Kline, “Alta Gracia: Branding Decent Work Conditions” (Washington: Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University, 2010).

50 Ibid.; WRC, “Verification Report Re Labor Rights Compliance at Altagracia Project Factory (Dominican Republic)” (2011).

51 World Bank, “Data: Consumer price index.”

52 World Bank, “Global Purchasing Power Parities and Real Expenditures: 2005 International Comparison Program” (2008), pp. 21–28.

53 See Anker, “Estimating a Living Wage: A Methodological Review,” p. 43. He critiques this methodology generally and Novartis’s living-wage studies specifically.

54 Ibid.

55 WRC, “Living Wage Analysis for the Dominican Republic”; WRC, “Sample Living Wage Estimates: Indonesia and El Salvador” (2006).

56 World Bank, “Global Purchasing Power Parities and Real Expenditures.”

57 See Office of Textiles and Apparel, Major Shippers Report: U.S. General Imports by Category; Letter from Donald I. Baker to Acting U.S. Assistant Attorney General Sharis Pozen, December 15, 2011.