AGE: 38

OCCUPATION: Former garment worker, labor organizer

BIRTHPLACE: Chandpur, Bangladesh

INTERVIEWED IN: Los Angeles, California

We first interview Kalpona Akter in Los Angeles after she speaks to the local branch of the AFL-CIO.1 At the panel discussion, workers from different points along the supply chain for a major U.S. apparel retailer—from the tailors who sew the clothes abroad to the warehouse workers who supply them to stores—compare stories of forced overtime, uncompensated injuries, and retaliation for bringing grievances to management. When it’s Kalpona’s turn to speak, she describes her evolution from twelve-year-old seamstress to activist to prisoner. She explains that in Bangladesh, garment workers often enter the factories as children, facing superhuman quotas for piecework, harassment and physical abuse from supervisors, and a minimum wage that comes out to about 20 cents per hour, by far the lowest of any significant garment-producing nation.2 Workers who try to organize face intimidation not only from their employers but also from politicians who opine that they should be grateful to have work at all, regardless of the toll on their bodies and spirits.

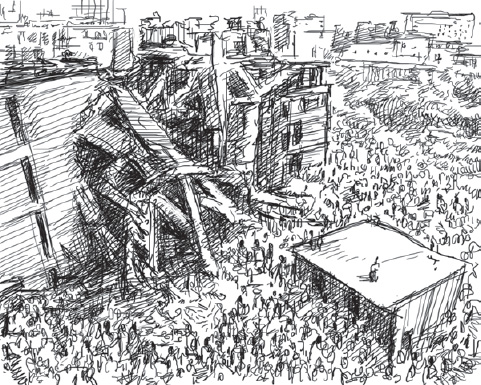

Bangladesh has nearly half the population of the United States, yet geographically, it’s smaller than the state of Florida. As densely populated as it is, the country still has a largely agricultural economy and, with a per capita income of under US$2,000 per year, is one of the poorest countries in Asia. Starting in the 1990s, however, garment production boomed as international clothing retailers began to take advantage of the country’s inexpensive labor supply and the Bangladeshi government encouraged investment with tax incentives. Today, Bangladesh is second to China as a leading exporter of apparel. Around four million garment workers produce US$20 billion worth of clothing for export a year; this figure represents the vast majority of the country’s total export earnings. Meanwhile, the garment workers themselves—mostly women—struggle to survive as wages decline compared to the cost of living, and abysmal working conditions lead to workplace disasters such as the Rana Plaza factory collapse in April 2013.3 For Kalpona and fellow labor activists, speaking out is not just a matter of achieving more favorable working conditions—it’s a matter of life and death.

AS A CHILD, I WAS SO NAUGHTY

When I was around six and in my second year of school, my family moved from Chandpur to Dhaka, which is the capital of Bangladesh.4 My first memory of Dhaka is of waiting with my four-year-old brother for my dad to come home from work in the evening. He worked as a construction contractor in the area around our home in Mohammadpur,5 and he used to bring home treats after work. He might bring us sugarcane, or it could be cookies, chocolates, or some fruit. He would bring home something for us every night. Besides my brother, I had a sister as well at that time, but she was only a year old and still nursing.

As a child, I was so naughty. I used to talk back to my mom all the time, and I irritated her with a lot of questions. “Hey Mom—why is Dad late?” “Hey Mom—why is the sky blue?” “Hey Mom—why isn’t it sunny? Why is it raining?” When she was cooking, I’d say, “I want to see.”

My mother used to cook all the kinds of traditional food we have in Bangladesh: dahl, fish, she could do everything. I remember that we had an oven but we didn’t have gas—it was a wood oven. We’d collect wood outside our house or buy it at market.

During that time our family had our own tin-roofed house, which is a common kind of house in Bangladesh. We had three bedrooms, two balconies. At the tin-roofed house, we had a backyard and front garden. We had guava and mango trees, and my mom also used to grow vegetables in the garden.

But we were forced to sell our house at a low price to a local politician. It was in a nice area of the city, and the politician put a lot of pressure on my dad to sell it. I don’t know too many of the details. Later I tried to speak to my dad many times about the nice house, but he didn’t want to talk about it. We bought a smaller house without as much outdoor space. My father changed parties and political views after that, though. He was really hurt and felt he’d been cheated.

I don’t remember exactly when we lost our house, but I was still in primary school. I loved school. There we learned Bangla, basic English, and math. Bangla is our native language. There was a small playground at this school where I would go and run around with my friends. Near the school playground, there was a bazaar, so sometimes my mom or dad would give me some money to have a snack or something cool to drink. I would buy fruits, ice cream, or some sour pickles—I was eating everything.

In Bangladesh we go to primary school until grade five, and then we go to high school. I passed the primary school and was put into grade six, at the high school. In high school up to the ninth grade, we studied Bangla, English, math, social science, and then science and religion. Religion was the last subject I studied. Every religion had its own class. So if you were Hindu, you’d study Hinduism. Muslims, they had Islam.6 All the students had other classes together, but we would split up for religion classes. We didn’t pray much at home, and at the time, girls and women were not allowed in the mosque. So religion class was where I’d learn about the life of the Prophet and how to pray. We didn’t have any choice of which subjects we studied, but I can remember that my favorite subject was science. I believe that I was one of the best students in my high school.

WHATEVER MONEY MY MOM HAD, IT JUST RAN OUT WITHIN A MONTH

Many people were building houses in Dhaka in the late 1980s, and my dad was a successful general contractor, or middle man—people would hire him to build the house, and then he would subcontract or hire others to complete the smaller jobs on the project. So he would often have a lot of money on him, because people would pay him the whole sum for the project and he would use that fund to pay other workers.

I have a cousin who was living with us and was also working with my dad. My dad started to entrust my cousin with the finances for the business. My dad would put the money in a bank account, and then my cousin could draw on it when he needed to pay subcontractors or other workers.

One day in 1988, just after I had turned twelve, my cousin took all the money my dad had entrusted him with and just disappeared. My family didn’t hear anything from him for a couple of months—he was just gone. And then, one day, he showed up again. He didn’t say he took the money, but he didn’t deny it either. He just didn’t take responsibility.

After the theft, my dad suffered. He had two strokes within two months of each other, starting about a week or two after my parents learned that the money had been stolen. One stroke after the other. The whole right side of my father’s body was disabled after the strokes, and he couldn’t speak for many years. He had to be admitted into the hospital, and my mom really had a very difficult time during his illness. She had to pay all the hospital bills because, as far as I remember, we really didn’t have health-care insurance or a health-care system in Dhaka back then. In any case, my mother had to find a way to pay all the medical bills herself. My father was back and forth to the hospital for maybe six months.

Whatever money my mom had, it just ran out within a month after my father’s strokes. So then she had to sell our house. We moved to a rental house. The rental house had about six rooms occupied by three families. We had two rooms to ourselves, but we had a shared kitchen and a shared toilet and shower. It was a disaster. There were maybe eighteen people total living in this small house. The house had a small balcony off of our rooms, and that is where my father stayed mostly while he was recovering. He’d sleep on a bed out on the balcony. It was too hot inside, and we didn’t even have a fan.

There was a lot of tension in our family at that time. My dad couldn’t talk. He had lost use of one side of his body. He couldn’t leave the bed, or even move. Within six months, we ran out of all the money we’d received from selling the house and all the other savings my parents had. We didn’t have anything.

My mom decided to go to my father’s other siblings to seek justice, or to have my cousin come and give us back the money he stole. But my cousin never came to our home at all. He refused to take responsibility. And it turned out that none of the other siblings wanted to help us. No one was helping us. There were six of us at home, or seven, after my littlest sister was born. We barely had enough food at home for my younger sisters and brother. And my dad needed to have his medicine.

My mom had never worked before—she had always been a housewife and we’d had a happy family. But because of everything that was happening, my mom decided she had to get a job. At the same time, Mom asked me whether I thought I should also work. I was twelve years old. And, because I saw what was going on in the family, I said, “Yeah, I want to work. But how I can get a job, Mom?” I didn’t want to quit school since I was doing well. I was even class captain for many months, but I felt I had to help my mother and father if I could.

There were some garment workers who used to live next to our house whom we’d known for a long time. Mom spoke to some of them, and they said that they would speak to the midlevel management at their factory to see if I could get a job. About a week later, our neighbors came and told me that they could get me a job. So one day I went to school and the next day I went to the factory.

MY FRIENDS ARE AT SCHOOL, BUT I’M STUCK WORKING HERE

I didn’t tell anyone that I’d left school. They began to worry after about two weeks, though. My teachers showed up at my house. They said that they wanted to give me some sort of scholarship to keep my studies going. But my mom said, “How can she go to school? There are still four other kids. They don’t have any food. Kalpona has decided to work.” My teachers kept insisting then that I should stay in school, that I should not work, but, you know, my mother had no other choice.

So I didn’t go back to school. I went into the factory, and my mom did too. She got a job in a factory far from our house. It was about ten kilometers away from our home. But I got a job in a factory close to home, maybe one kilometer away. I could walk there.

The very first day I went to work in the factory—oh my gosh—it was a crazy experience. There was so much noise, more noise than I had ever heard before, and people were shouting all over the place. Midlevel supervisors were yelling at the workers all the time. We had two buildings in the factory and around 1,500 workers all together, and everything just seemed like chaos to me at first.

Every day, I’d walk to the factory along with my neighbors who had helped me get the factory job. The supervisors at the factory first gave me a job cutting the belt loops in pants. The loops were made of four or more layers of fabric. I had to scissor the four-layered fabric, and it was tough. When I cut the fabric layers, the scissors made my fingers and hands hurt. I must have cut more than a thousand a day. Except for a couple of breaks to eat, I’d be cutting nonstop for fourteen hours a day, from eight in the morning until ten at night.

After my first couple of days, it was like my skin had been rubbed away. When my hands started to bleed, I would bind them with some pieces of fabric from the production floor. It was unhygienic, but I had to protect my hands so I could keep working. You can see these black marks on my hands. The very first day I hurt these fingers. These scars I got from that scissoring. I stayed on the belt loops for four or five weeks, and then moved on to a different job with a different order of clothing.

It was painful for me to go to work because my factory and my old school were so close. We would often go to the rooftop of the factory to have our lunches, and from there I could see the playground in my school, and I could also see my friends playing. I mean, almost every day during the lunch hour I would cry, because I thought, My friends are studying there at school, but I’m stuck working here. But I also had a brother and sisters. And when I went home and saw them, saw their faces, it would remind me that I had responsibilities that I needed to take care of.

IT WAS A VERY SAD PART OF MY LIFE

When my mom and I started working at the factories, my mom would wake up early to cook something like rice, dahl, or vegetables for the whole family—that was food for the whole day. While we were at work, my brother, who was ten at the time, would take care of my youngest sister, who was a newborn baby, my other two sisters, and my dad, who was still sick from the stroke. Sometimes my mother and I used to take food with us to the factory; sometimes we wouldn’t, because we didn’t enough food to take with us. Sometimes we would work the whole day without any food. And sometimes when I came home from work, I would see there was no food at home either, so that meant that my mom and I wouldn’t eat for two days.

It hurts sometimes, not having food. It makes you weak. But when you see that your younger siblings do not even have food, you don’t have any choice. My brother would not even eat the food we left for all of them in the morning. He would save this food for the two youngest and for my dad, because the two youngest used to ask for food all the time, so my brother would save his portion for them. So he was like a dad and a mom to them—he was raising them all by himself. He was ten years old.

After five or six months working at the factory, my mom got sick. She was dehydrated, malnourished, and the doctor said there was something wrong with her kidneys. She was so dehydrated that she couldn’t breastfeed my baby sister. She had a pain in her kidneys and it became impossible for her to work.

After she quit the job at the factory, she started feeling better. So we decided that instead of my mom, my brother would go to the factory with me. Around this time I also changed to another factory. The new factory was farther away, but I could make a little more money there. At the old factory, I could get maybe 240 taka in base salary per month, and maybe 400 to 450 taka per month after overtime.7 At the new factory, I could make a base salary of 300 taka per month and up to 500 taka per month with overtime, because I used to do the night shift as well.8 If I made 500 taka a month, I could pay for much of our rent——which was a little under 500 taka a month—but not for food. That is why we decided my brother should work at the factory as well. So I took my brother into this new factory and convinced my supervisor to give him a job. My brother got a job as a sewing-machine helper and started working in the building next to me.

There were other children working in the factories, too. The youngest child I saw in the new factory was a boy about eight years old. I think during that time I had been promoted to sewing-machine operator, and the eight-year-old was my helper. That eight-year-old boy used to cut the threads and pile up the clothes that I sewed. And I can remember he used to come in the morning and say, “Oh sister, I’m so sleepy.” He was a young kid, so you can imagine.

Our factory work used to start at eight, so my brother and I needed to get out from the house at something like six thirty or a quarter to seven. Then we’d walk about one kilometer to get the bus to the factory area, and then we’d walk about a half kilometer to get into the factory. And that is what we would do for three or four years, the same routine every week.

The factory is not far from where I live today. The site still exists and some of the buildings are still there. So I can see the factory every day, twice a day sometimes. When I see it now, sometimes I laugh. Sometimes it gives me pain. Sometimes it gives me lots of things to remember. It was in this second factory, too, that I met my future husband.9

It must have been around 1991 or ’92. He was in the embroidery section and he was a relative of the factory owner—I think a cousin or second cousin—so he’d gotten the job in a very easy way. I don’t remember how I met him, maybe when I was on the bus to the factory. Or while going into the factory or coming out, I saw him. I was seventeen years old when we got married in 1993 and I moved in with him and his family. I was so young.

If I want to, I can remember that part of my life, but it’s really painful for me. It was a very sad part of my life when I met him. The marriage was troubled from the start, and the factory workers were just beginning our fight at the same time.

WE REALLY GOT ANGRY

I remember how the trouble started at the factory. Basically we were working sixteen days in a row during Ramadan in 1993, right before Eid ul-Fitr, the breaking of the fast of Ramadan.10 We were working day and night, and the Muslims in the factory were fasting for Ramadan. We would fast over the day and break the fast in the factory with little snacks, and we’d eat our dinner after sunset with the little money that the factory provided. And then working the whole night and getting food at around three a.m., before fasting again after sunrise.

When we worked overnight, we might work ten hours of overtime, and the custom was that the factory would give us an extra five hours of bonus pay. In 1993, after we’d already done sixteen days of overnight work, management announced they weren’t giving out any bonus pay for overtime that year. They said they could not afford it.

And as I mentioned, it was before Eid, so when we were working those extra hours, we were planning to have the bonus money for the feast at the end of Ramadan. We really got angry. We didn’t have much of an idea about labor law or our rights as workers, but some of the senior workers said to us, “We will not work ten hours overtime without the bonus. We will strike until they pay us the amount they owe us.” I agreed with them.

I was one of the initiators of the strike. We had 1,500 workers in two units at the factory, so among the 1,500, it was 93 of us who called for a strike until the factory agreed to pay the bonus.

When I returned home the day we decided to strike, my husband had heard that I was involved, and he beat me. He was related to the factory owners, so he didn’t support the idea of a strike. At the time, I was feeling very helpless. Very helpless. But the next day, the day of the strike, I told some of the other ninety-three who were protesting, and they said that they understood and would always support me, that they wanted me to always stand with them, and that I was one of the courageous ones. We continued with the strike, and after a single day the management agreed to give us the bonus money. But they made it clear that they would not pay the same bonus in the future, and we agreed. At the time, we didn’t have any idea about the law.

After the strike, we factory workers went on holiday for Eid. After holiday finished, when we came back, we learned that twenty of my co-workers who had demanded the bonus money had been fired. The twenty fired workers were the ones the factory considered the main instigators of the strike.

The organizers decided they would not give up, and they started to look for an organization that could help them. And they found Solidarity Center. Solidarity Center is an international wing of AFL-CIO, the big U.S. union. The full name is American Center for International Labor Solidarity, but during those days, the branch we worked with was known as AAFLI: Asian American Free Labor Institute.11

The Solidarity Center had already begun helping a group of workers to form an independent union for garment workers, the BIGUF, or Bangladesh Independent Garment Workers Union Federation. The new garment worker reps met with some of our leaders and said they would help us to sue the factory owner for retaliation. And at the same time, they said they had awareness classes where my co-workers could go and learn about labor law, and then they could better take on their management. So some of my senior colleagues, they went to the law classes and they found it really interesting. They came to work and encouraged some of us interested in fighting back to go to the classes.

A SECOND BIRTH

It was around the end of 1993, and I was seventeen. I wasn’t allowed to go anywhere without my husband, or I had to at least tell him where I was going. He was a very controlling man, so I didn’t tell him the truth when I went to the labor classes at the Solidarity Center.

When I learned about labor law and rights, it was like a second birth for me. I thought, Wow, we are working in hell. So then I decided to commit to organizing. When I came home in the evening, my husband asked me where I had been. I told him the truth then, and he asked me, “Why have you been there? Did you get my permission?” I said, “No, I didn’t,” and so he beat me. But I was determined that I would not take a step backward.

So the next day, after realizing that there were all of these laws that were covering workers’ rights in the factory, during the lunch break, I started telling my co-workers that I had gone to the Solidarity Center and had learned a lot. And I brought some of their booklets with me to the factory. It was risky, but I had to do it.

Some of us started to meet in a small room in a co-worker’s house, which was close to my house. And we were also going to meetings sponsored by Solidarity Center for BIGUF. I had back-and-forth communication between BIGUF and the workers at my factory. The center was giving me guidelines for how I should organize. So I was really doing the organizing part and persuading our workers to sign the union application.

My husband was an anti-union guy. I didn’t listen to him. But once he discovered the signed union forms that I had gathered from my colleagues, he tried to take them and give them to the factory owner. So then I went to some of the other union members working at the factory that day, some of the local people who were very close to my husband. I explained to them what happened. And they ran up behind him as he was taking the forms to the factory owner and got the documents from him and told him not to do that.

I was beaten by him because of my involvement with the union, because I was helping to organize workers in his cousin’s factory. Also, when I tried to give some of my wages to my family, he beat me because he wanted me to give all my money to him, whatever I earned. So he kept me from helping my family, even though my family was so needy during that time. They needed my support, but I couldn’t help.

My husband had control of my life. But I felt like I couldn’t leave him because of cultural expectations. If I got divorced or left him, it would be bad for my younger sisters. I mean socially, it would look bad. The culture expects that if the eldest sister got divorced, then she must not be from a good family, and no one would want to marry any other sisters. So I had to tolerate my husband.

We were together for about nine months and then we had something like a settlement: a partial separation. We were staying in the same house, but in two separate bedrooms. I started sharing a room with his sister. And I was with him for a couple more years like that.

“IF YOU WANT TO FIRE ME, YOU HAVE TO TELL ME THE REASON”

I was eventually fired because of my work helping to form BIGUF. It happened in 1995. Some of my co-workers, I think they whispered about me, or maybe my husband told the factory bosses about my organizing. However they found out, they came to know that I was involved in forming a union. The bosses called me into the office several times to indirectly threaten me, and one time, I was suspended for twenty days without any reason.

Finally, one morning just after I had started my work for the day, a co-worker approached me and let me know I had been called to the office. I went to the office room and the bosses told me I was fired. But they weren’t just sending me home. They were offering me a good amount of money to leave. I don’t know how much it was, but it was a big bundle right there in the office. And they said, “You’re fired, you can take this money and go.” And I said, “I will not take any money. If you want to fire me, you have to tell me the reason.” And they said that they could terminate my employment anytime they wanted. And I said, “I know that you have the right to fire me, but you have to tell me why I’m being terminated.”

The company made a lot of drama. They wouldn’t state officially why I’d been fired. I sued them in the labor court. My husband was angry. Many of our mutual co-workers supported me, though, so he was careful not to come out too strongly against me. But he let me know that he would not support me, and he would not spend any money to take the case to court, and he would not allow me to spend any of my money on the case. Instead, I got legal support through BIGUF.

During that time, my dad still couldn’t walk much at all, but he got his voice back. So I explained to him, “I’ve lost my job and some difficult things are happening with my husband, and I need you to help me out.” But my mom wouldn’t agree with a separation or divorce because it would make it hard for my other sisters to marry. I hadn’t told my mom that my husband was beating me, because I didn’t want it to hurt her. So later I had to tell her that this was happening. I was like his slave, I told her. So then my dad said, “Okay. Move out.”

So I moved to my parents’ house. Six months after that, I divorced my husband. I lived with my parents and I would go out looking for work. I had trouble getting work in other factories, because I had been blacklisted. I found work in two other garment factories, but I was quickly fired from both of those jobs. The owners of the factory I was suing, they informed those factory owners who hired me that I had sued them in the labor court. The bosses at one factory, they told me that I could continue my job at that factory if I withdrew my case against my previous factory owner, and I said no. So they fired me.

The BIGUF gained official union status in 1997, around the time I was being blacklisted, and so I checked in at the new BIGUF union office. I told them what was happening to me, and that I couldn’t get a job anywhere. So at first they appointed me as an intern organizer for three months. And then they appointed me as a full-timer with the union up to 1999. That’s when my court case was dropped, and the judge ruled that the company that had fired me owed me only my severance pay.

When I was working full-time at BIGUF, my task was to organize workers door-to-door. In the mornings before factory shifts started and in the afternoons during the factories’ lunch breaks, I used to go to the areas outside the factories to organize workers, to tell them there’s an organization where they can come and learn the law and their rights. And in the evenings, I had to do house visits, to go to the workers’ houses and speak to them there. And on Fridays there were awareness-raising classes. During those classes, I had to give a lecture about basic law and rights, what I had learned coming to BIGUF, and my life before I joined them. My task was to educate workers.

ACTIVISM WAS IN MY BLOOD. I COULDN’T HELP MYSELF.

In ’99, I quit the BIGUF. The BIGUF would work only for garment workers; many other kinds of workers used to come to our union office to get support, but we couldn’t help them. It was frustrating not to be able to help. So I quit, and I decided I wouldn’t work for labor rights anymore. I’d had a bad experience: I’d lost my court case, I couldn’t find work, and I couldn’t help a lot of people who needed help. So I thought I would do something else, like set up a small shop selling food or other little things close to my house. I thought, I can survive with that.

But you know, activism was in my blood. I couldn’t help myself. Many workers knew my face, they had my contact info. The workers used to call me and ask for help, and I couldn’t help them because I wasn’t with a union anymore. Then, around the end of ’99, one of my former union colleagues, Babul Akhter, contacted me. He said, “Let’s do something ourselves!” So Babul and I started our own program that year through sponsorship of the international Solidarity Center, and we called it the Bangladesh Center for Worker Solidarity, or BCWS. The formal launch of the BCWS was in August 2000. I was about twenty-two years old.

We got funding from the AFL-CIO and organizations like the International Labor Rights Forum.12 Our whole philosophy was that our organization was going to be a long-term commitment to all workers. And we were going to work in an innovative way. If you talked about unions in Bangladesh, the factory owners would say, “Oh, unions are evil! They destroy everything.” We wanted to change those perceptions, so that not just the workers but everyone else would have respect for unions and for workers’ rights. Our focus was on providing information, so we made posters and pamphlets and met with workers to inform them about their labor rights. We wanted to train female garment workers to form their own organizations, to speak out themselves about their rights. So that was the beginning of the BCWS. We were pretty successful for the next few years. I think the BCWS was doing a great job achieving our goal of raising workers’ awareness about law and rights, helping them to handle their grievances, giving them legal service, legal support. Helping them to grow their leadership capacity. Giving them educational programs, helping working mothers get educations. So that was really successful in the following years, after our formation.

We also wanted to form a kind of federation that could be a national voice for the workers, more of an actual union rather than just a source of information about unions and labor rights. So in 2003, we were able to do that. I helped found the Bangladesh Garment and Industrial Workers Federation, of which Babul is the president. The two organizations work out of the same office, but have different functions. BCWS is an NGO and our mission is educating workers about their rights, and BGIWF is a union federation that has the legal power to help workers negotiate with their employers and assist other unions.

During this time I was still living with my family. Luckily, even though I had been divorced, two of my little sisters got married. We remained very close after they moved out and started having children. My younger brother joined me in helping to grow BCWS as well; he’s been a big source of support. My parents, too—my family has stuck by me through everything I’ve faced.

AT THE BCWS, WE DID NOT SUPPORT VIOLENCE

In 2006, there was a big uprising of workers across the country. The major issue, among other issues, was that there was a big gap between workers’ wages and the cost of living in Bangladesh. The minimum wage of 950 taka per month was set in 1994. And factories weren’t even complying with that standard.13

At the BCWS, our position was to support the workers and help amplify their voices on issues like a new minimum wage. During the uprising, some property was vandalized and damaged across the country. There was a lot of violence between political parties leading up to national elections as well. At the BCWS, we did not support violence and damage to property. None of us had any prior idea about this movement, or this uprising. It wasn’t planned, it just happened. But the uprising had an impact. Afterward, the minimum wage was raised and better enforced.14

But it was also after that 2006 uprising that Babul and I began to feel that the government had taken notice of the BCWS. They started to follow our work around that time. They would visit our offices, follow our activities, and seemed to be watching us closely.

Worker associations in Bangladesh such as Kalpona’s BCWS and BGIWF made gains throughout the early 2000s, including the legalization of worker association groups within free trade export-processing zones and updates to minimum wage and worker safety laws.15 In 2006, a string of violent confrontations between political parties and a series of labor strikes effectively halted the nation’s economy. President Iajuddin Ahmed declared a state of emergency and turned the government over to a military-run caretaker regime. The emergency resolution also suspended the right to assembly and granted police the power to arbitrarily detain citizens for any length of time. Though elections would be held again in 2008, abuses by police, including arbitrary detentions, continued.

In April 2010, we started hearing serious threats. Babul was approached by an NSI agent who told him that we needed to stop talking about labor rights with workers or the agency would take strong action against us.16 Then, in June 2010, the Bangladeshi government decided to revoke BCWS’s NGO status registration. This was a big deal, because if we wanted to have foreign funds to run our programs or activities such as educating workers, we had to have registration with Bangladesh’s NGO Affairs Bureau. So all of the backing that we got from international organizations like the AFL-CIO was no longer legally available to us. The government stated that our registration had been revoked because we were doing antistate activity—which was not true. And they didn’t give any proof or any evidence of that. We weren’t sure what kind of work we were still legally allowed to do since our license was revoked, but we were meeting at the offices anyway. Now we no longer had any funding, and we were certain then that there was a campaign being waged against us.

And that’s when we had our first confrontation with the NSI. It started when the chief inspector of factories with the Labor Ministry, someone we had worked with before to resolve worker conflicts, called us to come help settle a dispute between striking workers and their company, which was called Envoy. I reminded him of our registration issues and asked that he make sure we wouldn’t have trouble with the government if we participated, and he agreed.

We sent one of our colleagues, Aminul Islam, to gather a group of Envoy workers as representatives to bring to the meeting at the Envoy offices. Aminul was an excellent negotiator and one of the most effective members of our staff at BCWS and BGIWF. He’d been with us since 2006. He’d been a worker in a garment factory as well, just like me and Babul, and he had been quite successful organizing in some of the factories in Ashulia, a big industrial zone just outside Dhaka.

So Aminul was able to gather about eighteen workers and headed off to the meeting. Babul and I were trying to get there as well, though we were running a bit behind Aminul. We were on our way to the meeting when we got a call. Another one of our colleagues who had arrived at the meeting said that men had stormed in and blindfolded Aminul and taken him off just after they’d arrived. Our colleague who was telling us this had gotten away himself, but he said that there were men waiting for us and that we shouldn’t come.

We were shocked. First we called the chief inspector and demanded to know what had happened. We were really yelling at him, but he wouldn’t tell us about Aminul or promise to protect us. He wouldn’t say anything, really. Then we called every police force and security agency contact we had, but nobody would tell us anything about Aminul.

Early the next morning, June 17, another BCWS colleague got a call. It was Aminul. He was crying, terrified. He said he’d been picked up by the NSI and driven north of the city where he was interrogated and beaten. The NSI officers had asked him things like: Why did you stop the work at the garment factories? Who ordered you to stop the work? Why? Tell us his name. Tell us if Babul asked you to stop the work at factories. The persons who told you to stop the work at factories should be punished. If you just say that Babul and Kalpona asked you to stop the work at the factories we will set you free. We will arrest them in a moment and take them here.

Aminul had managed to escape in the middle of the night when they’d let him out of their vehicle so he could pee. We were able to get Aminul to a safe place and get him medical attention, but he was badly wounded. His toes had been broken and he had a lot of internal hemorrhaging from being struck with a stick across his back and head. He told us the NSI had tried to get him to sign confessions and implicate me and Babul in all sorts of antistate activities like inciting riots. We knew we were being closely watched, but eventually we got Aminul back to his home so he could be with his family.

WHEN THEY ARRESTED ME, MY HEAD WAS BLANK

Then the next trouble started with a demonstration in Dhaka on July 30, 2010, in which there was vandalism and property damage. The issue at the time was that the government was set to raise the minimum wage again, and on July 30 it was announced that the minimum wage would be raised to 3,000 taka a month.17 Many worker advocacy groups had advocated for much more than that, because inflation was making the cost of living much higher very rapidly. So there were demonstrations on July 30 protesting the new minimum, and some vandalism took place five kilometers away from our main office. But we at BCWS weren’t involved. I was at a staff meeting thirty-five kilometers away, and I didn’t know anything about the incident.

While I was at the staff meeting, I heard about the demonstration and vandalism through a U.S. embassy officer that I knew. He was on vacation in Malaysia, but he texted me, and he said that there was something on television about an uprising going around the factories in Dhaka. And he wanted to know whether we were safe or not. So I started checking in with some people, and I called one person I know in the Dhaka office. He said he and some other colleagues were in the office and had locked the doors, and that they were all safe.

After that, I went home. In the middle of the night, maybe around midnight, Babul called me and said that in the newspaper there was a story about the demonstration. The story mentioned that six criminal cases had been filed, and our names were there. The story claimed that our organization had helped start the unrest. And I said, “What’s going on, it’s crap! We weren’t there.” I was a target, Babul was a target, and so was Aminul, as well as a few organizers from other unions. They were charging us with things like inciting riots and using explosives. Very serious charges.

So the next day, a Saturday, we started calling my colleagues and our lawyers and informing them about what was happening. We also started to talk to those other federation leaders who had been accused in similar cases.

Soon the police started looking for me and began to bother my sisters and their husbands, threatening and harassing them to try to find where I was. That’s when Babul and I went into hiding. We were able to stay in a safe place we’d set up in some unused BCWS offices until August 13, when the police finally found us. They stormed in early that morning. It was still dark. When they arrested me, my head was blank. I couldn’t understand what was going on. I wasn’t sure what to do. They shined flashlights in our faces, cuffed us, and took us to the police station.

Babul was sent to a cell. There was no cell for females so I was told to sit on the floor in a tiny, dirty office room. They forced me to sit squeezed behind a desk and a wall. The two-by-four-foot space was so small I couldn’t even lie down. That’s where they kept me sitting, cramped for seven days. I couldn’t sleep the whole time. I would lean against the wall and maybe nod off at moments, but I could never fall asleep fully. The whole experience was so scary. During this time, the police would take me out of the space only for interrogation. They would interrogate me at any time of day for two, three hours. The longest session was something like eighteen hours in a row.

They would ask the same few questions over and over. Sometimes just to me or just to Babul, sometimes to both of us together. They would ask questions like: Who funded us? Was there any international organization or any specific country who was giving us funding to destroy the garment industry of Bangladesh? Who were the other organizations we worked with? Why did we start the recent unrest?

When we stated that we hadn’t anything to do with the incident in July, they’d say, “Then tell us who is responsible, we have to bring them in.” They wanted us to talk about our families, our international connections, basically tell them about everyone we knew or had ever worked with. There were maybe a dozen interrogators who would take turns asking Babul and me the same questions over and over, thousands of times.

After a week of interrogation, we were brought to the courthouse for our initial hearing. We were charged with vandalism, arson, and inciting riots. I faced seven charges and Babul faced eight. After that, I was sent to central jail for another three weeks.

The central jail was like something from a century ago, except there was electricity, but we actually couldn’t turn the lights off at night. I was with about 130 other prisoners. We could take showers only rarely, and when we did it was in an open courtyard in full view of everyone, including male prisoners held in another part of the same facility.

A couple of days after I was sent to central jail, my sisters brought their children for a visit. By this time I had a nephew who was about twelve and my nieces were about nine and five. The prisoners were allowed visits from family once a week, and we all gathered in a big room that was separated in the middle by two nets a couple of feet apart. It was loud, and the only way we could hear each other was by shouting. I remember my nephew and nieces just crying, asking why I was in this place and why they couldn’t touch me. I remember one of my nieces trying to reach me through the netting. I was just crying the whole time. I couldn’t even talk, really.

While I was in central jail, Babul was taken to a police station in Ashulia, the industrial park where some of the vandalism and arson supposedly occurred. There he was severely beaten many times, usually with a stick against his back. It got so bad that Babul gave a fellow prisoner his wife’s and lawyer’s phone numbers and asked that he call them when he got out to let them know what had happened, because Babul didn’t think he’d be leaving the prison alive. The worst was on August 30. He was assaulted by several non-uniformed persons who entered his holding cell, blindfolded him, and beat him with a thick wooden stick, inflicting injuries on his leg, hip, and groin. Babul’s assailants also threatened him, telling him that he’d be taken from the police station and shot by police during a staged incident. The same threat that was made against Aminul when he was detained by the NSI on June 16.

After thirty days in jail, Kalpona and Babul were released on bail, along with their colleague Aminul, who had been arrested and sent to a different facility, where he had also been beaten. The three continued their regular worker training and organizing work while awaiting trial until April 4, 2012, when Aminul was kidnapped outside the BCWS offices, tortured, and killed. His body was discovered sixty miles north of the BCWS offices with broken toes and massive internal bleeding. Signs point to NSI involvement in the murder, but so far no perpetrators of the crime have been brought to justice. Lack of progress in the murder investigation quickly raised concerns of cover-ups to protect security forces. Meanwhile, labor leaders feared for their safety. Eventually, Aminul’s death led to major international protests, including condemnation by U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton on a trip to Bangladesh in May 2012.

I DON’T WANT TO BRING SOMEONE INTO THIS WORLD WITH THE STRESS THAT I’M FACING

I still live with my parents. They’ve been through so much stress. For years they were harassed by the police, security agents, anonymous calls. They’ve been through a lot, and I worry about their helth. My siblings have suffered harassment as well. Still, we are a close family. My younger brother has worked by my side at BCWS. He’s had a difficult time as well, but he remains so strong. And I’m very close to my nephew and nieces. Very, very close. I mean, they call me “Mom.” Yeah, sometimes my sisters get jealous!

My family has always been such a comfort for me. I have one strong memory of being picked up by the police in the courtyard just outside my house and put in a van to go to trial. My family was there, including my nephew. It was a very hot day, and I was sweating. After the van started to pull away, I heard my nephew running by the van, crying out to the police, “Where are you taking my Mom? I want to give this to her!” The police asked me if he was my son, and I told them he was. So the police stopped and took something from him and handed it back to me. It was a paper fan. I shouted through the window to my nephew that he should go back home. But I was very touched.

I’m just crazy about babies. I want babies myself, but I can’t figure out how that would happen. I don’t have time to think about being a mother. And of course you need an appropriate person. You cannot have a baby with an irresponsible person. So this is another reason. And sometimes I think if I really do want a baby, why don’t I try in vitro fertilization? So then I need to figure out who could be the donor for this. And he has to have a good soul, at least. I just don’t have a lot of time to think about it all. This is another problem with having babies myself: I am doing too much work, there are too many stresses, and I don’t want to bring someone into this world with the stress that I’m facing.

In June 2013, two months after the Rana Plaza collapse captured the attention of the world, the United States announced that it was suspending certain tariff-reducing preferential trade benefits with Bangladesh because of serious labor rights violations. Part of the Bangladeshi government’s response has included dropping most of the charges against Kalpona and Babul and formally reinstating BCWS as an NGO in August 2013. It remains to be seen whether the government of Bangladesh will carry out a full investigation of the torture and murder of Aminul Islam and bring those responsible for his death to justice.

1 The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations is the largest federation of unions in the United States, made up of over fifty-six national and international unions from dozens of industries. In all, the AFL-CIO represents over twelve million workers both in the United States and abroad.

2 This figure is based on the Bangladeshi minimum wage rate of 3,000 taka per month from November 2010 to October 2013.

3 For more on the Rana Plaza collapse, see Appendix III, page 353.

4 Chandpur is a city of 2.4 million located sixty miles southeast of Dhaka, the capital of Bangladesh. The Dhaka metropolitan area has a population of over fifteen million.

5 Mohammadpur is a neighborhood in Dhaka that was first developed in the 1950s and experienced a construction boom in the eighties and nineties.

6 The population of Bangladesh is nearly 90 percent Muslim and 9 percent Hindu. Though the country is predominantly Muslim, principles of secular government were written into the original constitution in 1972.

7 In 1994, 240 taka = approximately US$3.80. 400 to 450 taka = approximately US$7.

8 In 1994, 300 taka = approximately US$4.75. 500 taka = approximately US$7.90.

9 Kalpona has asked us not to name her husband or use a pseudonym.

10 For the month of Ramadan, observant Muslims fast from dawn until sunset every day. Eid ul-Fitr is a major feast marking the end of Ramadan and traditionally includes lavish meals and charitable giving. Depending on local tradition, the holiday may last from one to three days. In 1993, Ramadan began in February.

11 The Solidarity Center, or American Center for International Labor Solidarity, was launched by the AFL-CIO in 1997. Its purpose was to help develop union representation for workers in developing economies, and it replaced earlier, regional AFL-CIO union-development organizations such as the Asian American Free Labor Institute (founded in 1968).

12 The International Labor Rights Forum is an international non-profit coalition of human rights organizations, academics, and faith-based communities that seek to address labor rights concerns in the developing world. For more information, visit www.laborrights.org.

13 In 1994, 950 taka = US$18.

14 In 2007, minimum wage in Bangladesh was set at 1,663 taka a month (approximately US$23 per month) and then raised again in July 2010 to nearly 3,000 taka a month (approximately US$43 per month at the time of the wage hike, but devalued to below US$40 per month by early 2014). For more information on wages in the garment industry, see Appendix IV, page 366.

15 Export-processing zones are designated geographical areas without export tariffs or taxes. See glossary, page 348.

16 The NSI is the National Security Intelligence agency of Bangladesh.

17 In 2010, 3,000 taka = US$43.