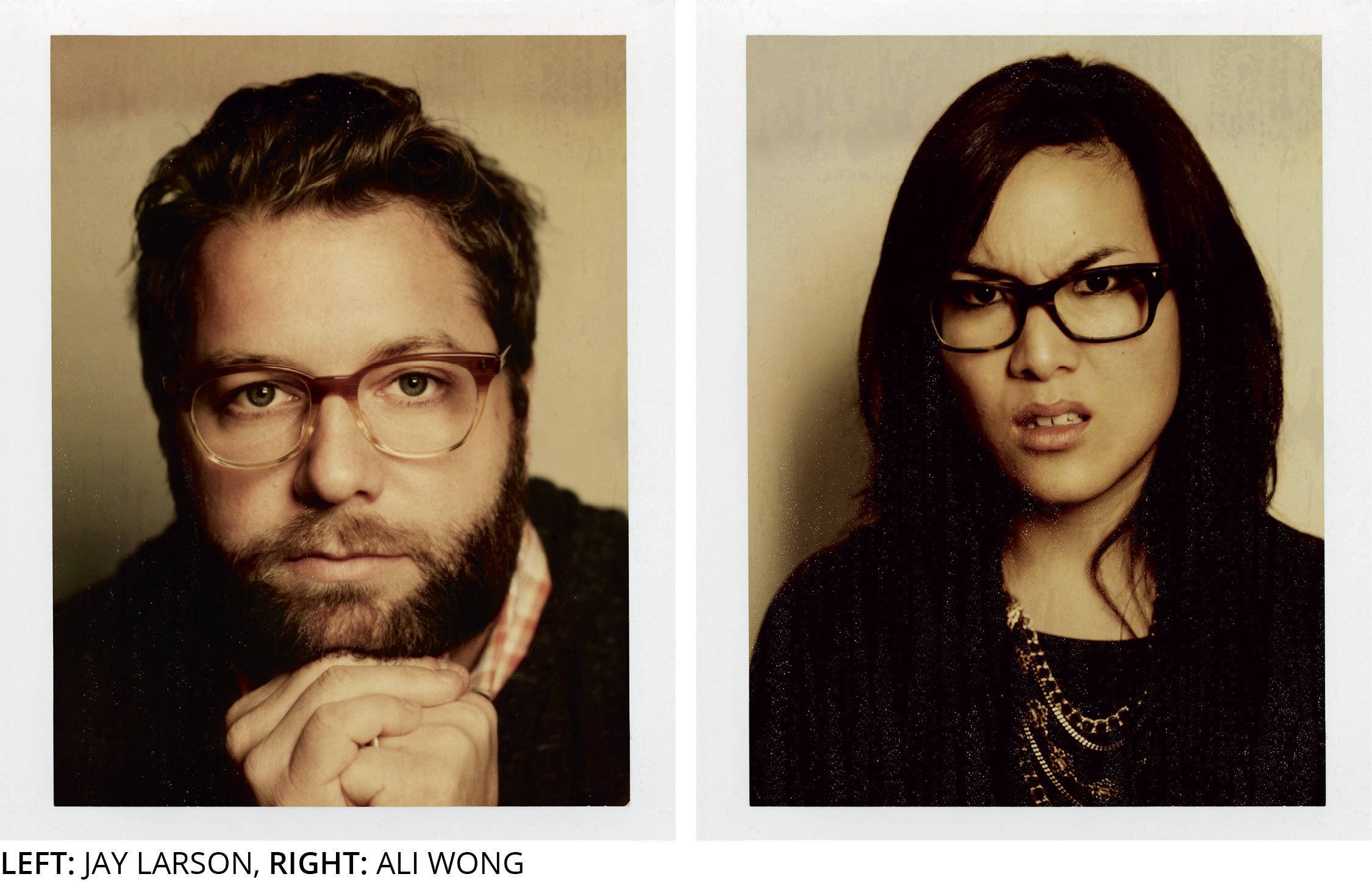

Eddie Pepitone: For me it was just completely the only thing that I ever wanted to do or was meant to do. I never had any thought of doing anything else.

Mandee Johnson: How did you know that?

EP: Through television. I was born in 1958, so I am sixty. I grew up watching Jackie Gleason and The Honeymooners. I loved Gleason. That big, loud, bombastic guy with a really soft underside. Heart-of-gold type of guy. I love that. I loved Don Rickles when I was younger. When I was fourteen years old, I smoked my first joint, and I started listening to Carlin and Pryor.

I had a fucked-up family life: my mom was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, and she was in and out of institutions, and my father was trying to hold the family together, and he didn’t really do it. My salvation was comedy. It’s cliché, but it’s true. I never thought of doing anything else. I took acting classes, and every time I did a scene dramatically, like Death of a Salesman or whatever, people would laugh hysterically. I knew I was destined for comedy. I started doing open mics in New York City, and it was terrifying.

people would laugh hysterically

-Eddie pepitone

MJ: What year was that?

EP: Let’s see, Kennedy got shot in 1963.

MJ: I love that that’s a reference point for your stand-up career.

EP: I was five when he got shot. I was around . . . I was eighteen, nineteen.

MJ: So thirteen years after Kennedy was shot.

EP: We landed on the moon in ’69.

MJ: So roughly seven years after that.

EP: It was around 1976, ’77, something like that.

MJ: How was the open mic scene in New York?

EP: It was horrible. I just remember going to a place—it’s not there anymore—called the Eagle Tavern. And everybody would go there, and I just was so terrified that I would throw up before shows. I would throw up backstage for shitty open mics. Then, I would go onstage and scream. It was crazy.

MJ: So nothing’s changed.

EP: I knew you were going to say that. I wish I didn’t know you were going to say it. But I knew you were.

Dana Gould: I was the fifth of six kids, and I was very much the runt of the litter. All my brothers are not only manlier, they’re all physically a foot taller than I am—it’s like my mother’s body was out of testosterone. Just me and then I had a sister. That’s true. And I was never an athlete. They always played sports, and they hunted, and I was just a TV kid. I gravitated toward horror movies and Star Trek but also comedy, and specifically as a kid, I was really into George Carlin, even though I was a kid. And then in the mid-seventies he was on TV a lot. Everyone in my family loved him. So it was one of those things where when he was on television, everybody shut up, and I was like, Oh, this is good. And being funny was a great way of getting attention.

MJ: Sure—big family, lotta kids.

DG: Yeah, big family, lotta kids. It was a great way of getting attention, and because I watched a lot of television, I ingested all of those rhythms and those patterns.

MJ: The timing.

DG: Yeah. And different algorithms for what’s funny. I ingested them really early—ten, eleven, twelve years old.

Dave Anthony: Oh my god! I always wanted to do stand-up—since I was five.

MJ: What inspired you at the age of five?

DA: There was just never anything else I wanted to do. I would just watch comedians on TV and just became obsessed with them. I don’t know why. Maybe my parents let me stay up late? Or maybe comedians used to be on earlier, but I would see them all the time. And then in my high school years I remember An Evening at the Improv came on after SNL, so I would sit there and watch it till I fell asleep.

My parents were divorced, so when I got to be like ten or eleven, my mom would go out on the town at night, and I would just sit there and watch TV. She would come home and try to get me off the couch to go to bed because I was on the couch watching stand-up until I fell asleep. I never really had any idea of doing anything else with my life. That was always what I wanted to do.

So it was always waiting, like it was a matter of time until I could start. In high school I would just write jokes. All of my binders would be full of me writing jokes. They were also not good jokes.

Barry Rothbart: I grew up in New York, and my dad would take me to the Comedy Cellar when I was really young, like when I was twelve.

MJ: They would let you go in?

BR: Yeah.

MJ: That’s crazy.

BR: Isn’t that weird? Yeah, we went every week, and I just thought it was magic. I wanted to try it one day. I secretly started keeping a notebook of jokes without telling anyone because I thought it was insane.

Randy Sklar: We were huge fans of comedy. When we were kids, our parents were funny. Our dad was funny.

Jason Sklar: He always made people laugh! Right?

RS: Yeah. He wouldn’t, like, write jokes or anything. But he’d take us with him on Saturday mornings when he’d go down to his office that he worked at, and then we’d run his errands with him and we would just sit in the car. He would go pick up his cleaning, and within thirty seconds of being with anybody, they would start smiling or laughing. So you see that over and over again, and you’re like, “Oh, that’s important. That’s valuable.” That’s the way you’re supposed to interact with people is to get them to laugh and smile.

JS: Or just it was a way of connecting with people.

RS: So we’re like, “That’s valuable.” That just has an impact on you as a kid.

Chris Garcia: Well, it was my childhood dream, so I always wanted to do it. I did it in little ways along the way. In elementary school, in Catholic school, the first time I guess I ever did it . . . I guess it was a forensics class or a speech class, and we’re supposed to do a speech from the point of view of an Old Testament prophet. And I chose this person Habakkuk. I didn’t know anything about him, but I had a friend who lived down the street who was Lebanese, and his family had the whole attire. I borrowed it, and they said, “OK, Chris, it’s time for your report,” and I had it all in a bag, and I went out in the hallway and came in with this costume on, like, “I am Habakkuk!”

I didn’t know that I was wearing what this nun thought was anti-Christian attire. I was wearing traditional Muslim clothes.

MJ: What a closed-minded nun.

CG: I know.

MJ: You got in trouble?

CG: I got in trouble, but the kids loved it. It was so fun. It was really fun and creative, and I was like, I think I can do this.

Paul Danke: I’ve been doing comedy stuff since I was a child. Forever. Doing voices and sketch stuff. My high school had an AV club, and they put on a weekly show, so we started writing sketches for it, and it was such a cool experience to get to do that. It aired closed-circuit for the school, and, you know, sometimes we’d do things that would offend some of the school, and we’d have to apologize for it. It was a truly incredible experience to write and act.

MJ: Really pushing the limits in the beginning, huh?

PD: Well, when you’re a teenager, you can’t help it. You’re just being funny. They’re like, “Have you thought of this?” And I’m like, “Oh my god, no. Literally never thought about it.” But it really made for some of the more interesting content of having to apologize for bad behavior or addressing bad behavior. It was really cool. Just from that I’ve done [comedy] ever since, and then in college I started doing stand-up.

MJ: How did you get into stand-up?

PD: My college started a late-night show while I was going there.

MJ: You just really got blessed with all these schools.

PD: I did luck out going to very liberal-arts-geared schools. I started writing monologue: twenty jokes a week off of the news. I did that for a year and a half. It was awesome.

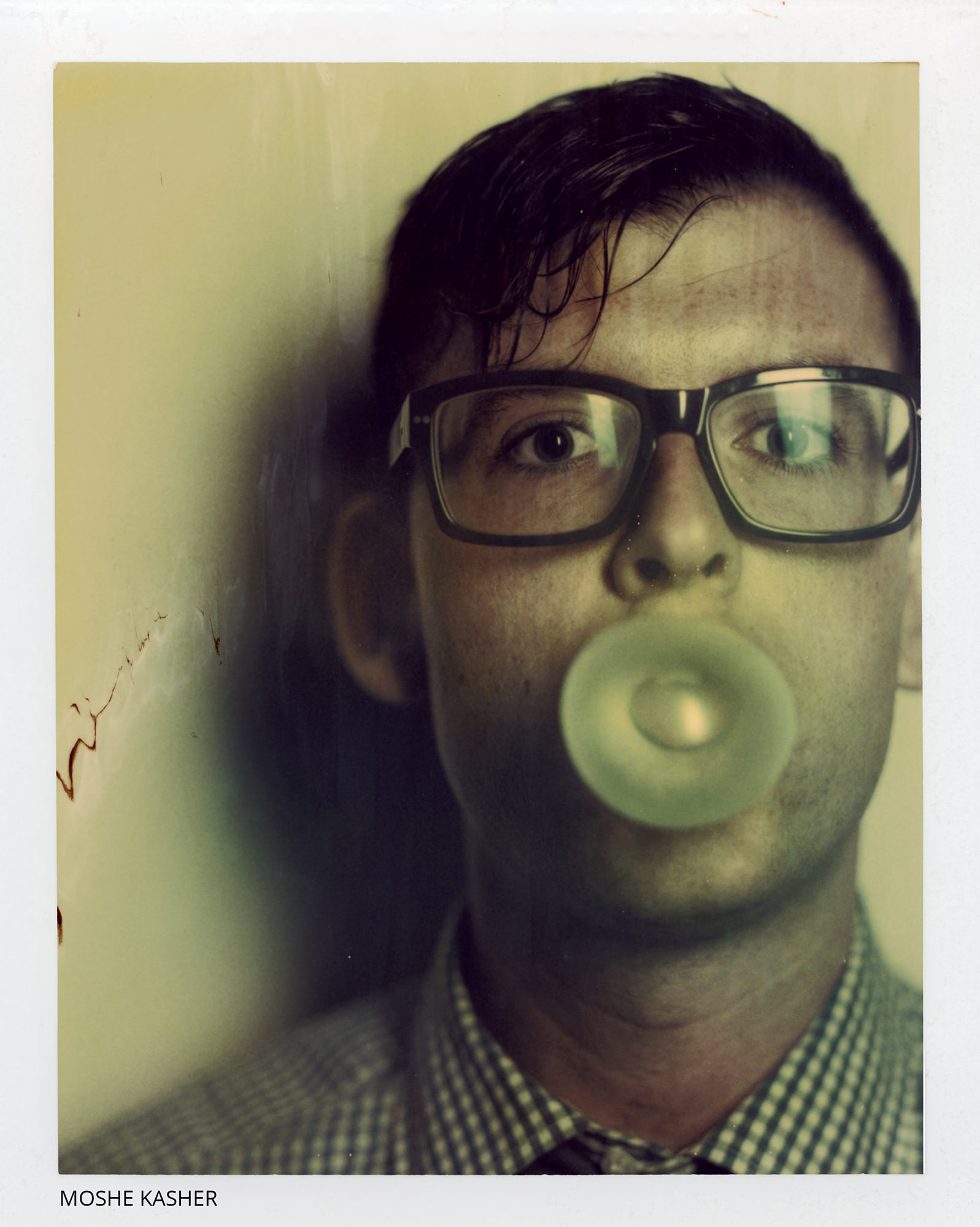

Hasan Minhaj: I started in Davis, and I would drive up to Sacramento and do open mics, and that’s when I met people like Brent Weinbach, Sheng Wang, Ali Wong, Arj Barker, Kevin Camia, W. Kamau Bell, Moshe Kasher, and Louis Katz. Those were the big comedians in San Francisco. They were starting to later become really big. And I remember just seeing the diversity. That was really inspiring to me to see the diversity of stand-up voices. Any given Sunday at the Punch Line in San Francisco—that’s the showcase night I would see—those six or seven or eight. You know, Drennon Davis, Kevin Shea, Jasper Redd—it was so inspiring. That’s what I thought comedy could really be. I think I got spoiled early on in life that a lineup would be that diverse—ethnically, style-wise, gender-wise. There were so many different types of voices. Then it was totally normal and not a thing that had to have a think piece written about it. It was just a reflection of who was a part of that community, which is really cool.

Rory Scovel: I think I stumbled into doing it. The reason is because it’s a job that only requires my personality—the foundation of it is simply me being myself. It was a thing that totally blossomed completely naturally and organically throughout my entire childhood: loving being a class clown who would do idiotic stuff just to get people to laugh. To fill the need my attention craves. I realized I can get that filled by being good at sports.

Joel Mandelkorn: You’re good at sports?

RS: I come from a sports family and a family of smart-ass, asshole, class clown people. So everything about me is a direct product of my family. Now I’m passing it on to [my daughter]. Notice how she doesn’t like that I’m getting your attention? It’s in our DNA.

MJ: When you were in D.C. and New York, did you do mostly clubs?

RS: Not at all. I didn’t come up in a scene where you went to the comedy club to perform. You got to perform there once in a blue moon. The only time we went to clubs was to stand in the back of the room if there was someone we wanted to watch. So for me, I’m used to performing in a scene where you go to the coffee shop, to the bookstore, to someone’s house to do a show; you go to a random bar, mostly bars . . . in a back room.

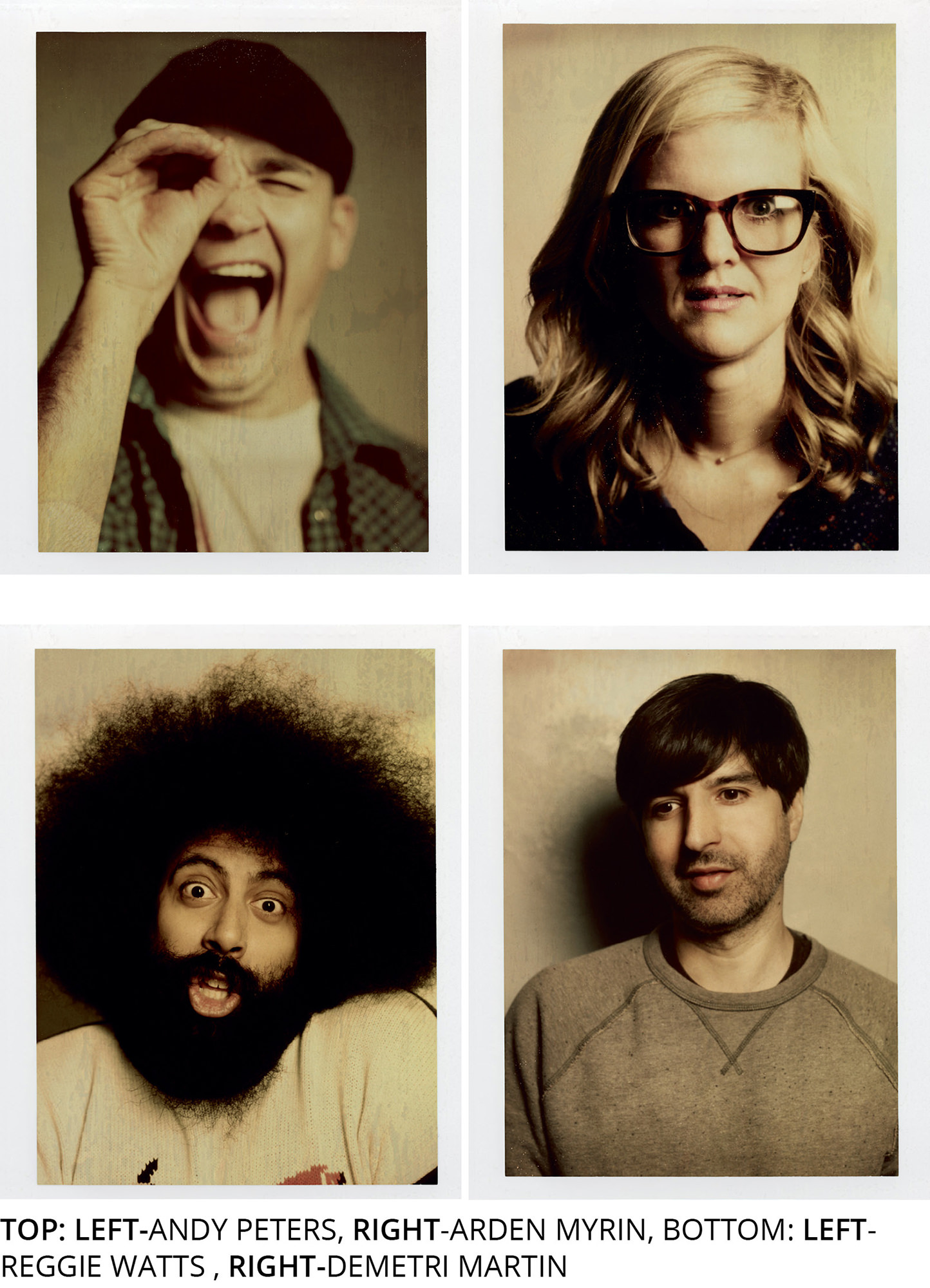

Demetri Martin: I started in New York, and I was in law school, and I went to law school right out of college. I’d say a couple of months into the first year, I realized that I’d made a mistake. It wasn’t going to be for me. But I’d only thought of being a lawyer since seventh grade or something. I had a crisis that second year of law school, which was my quarter-life crisis or midlife crisis, depending on when you die. I was like, “What do I like doing? If I didn’t have to worry about money and I woke up each day thinking about what I looked forward to doing? You know, I like joking around with my friends. I I think the idea of doing comedy would be cool.”

One day The Daily Show comes on—it was new one with Craig Kilborn. They just started having a studio audience, and it said on the screen, If you want tickets, call this number. I called the number. I said, “Hi, yeah, I’d like tickets to the show,” and also for some reason when I was on the phone, I said, “Hey, do you guys need any interns?” They said, “Yeah, we’re hiring interns now; we’re actually interviewing for the next semester. When can you come in?” I said, “I can come in tomorrow.”

So I went in and I interviewed. I wore a suit (because for law school, for my scholarship interview, I had this suit). I got out of the elevator and I walked through the office, and there were all these people my age looking at me like, Who is this young Republican coming to The Daily Show? I was looking at them like, Wow, I didn’t even realize. I had such blinders on from [going from] college straight into law school.

I interviewed, and they said, You need to get credit for school, because we can’t pay you. I went back to school, and I thought, Shit, there’s no unpaid internships in law school; that’s not how it works. You take contracts.

I had a scholarship, and I go to the director, and I say, “Hey, I want to do this internship at this TV show; would you approve it?” He told me, “You know I can’t approve it; you can’t get any credit for it.” But he said, “I’ll tell you what: if you write a letter, and it’s not a lie, I’ll sign it, and you can do your internship.” So I wrote, “I, the director of this program, approve Demetri Martin’s internship; upon the completion of his internship he will receive appropriate credit.” Which is zero. And he signed it, which got me into The Daily Show.

MJ: It wasn’t a lie.

DM: It wasn’t a lie.

Sara Schaefer: I moved to New York, kind of straight out of college. I didn’t know anything about comedy. I had done no research. I had never seen stand-up in person before; I’d only seen it on TV. I did not know what kind of comedy I wanted to do. I just wanted to be a funny person. I went to New York with all these big plans and then immediately didn’t know what to do.

I tried to do little sketches at open mics, and it was a fucking disaster. My partner was this robot, and I was her creator . . . it was a mess. We did two shows with that robot sketch, and it was awful.

MJ: But think about how much you learn from that.

SS: I did. And I didn’t do comedy again for like a year. But then about a year later, I got an idea for a bit. I wrote a song about my cubicle because I was working at a law firm during the day, and it was really dramatic. It was an angsty ballad about my cubicle. I wrote like a jazzy spoken-word piece about Excel spreadsheet programs. Very Office-y humor but that was my life. Write what you know, and I hated my job. I just thought, How am I going to do this?

Demetri Martin: The summer of ’97. I finally decided I’m going to drop out of school and just go for it. I dropped out before I ever got onstage, but I decided, I’m doing it whether I suck at it or not. I’m going for it. I did an open mic on Monday night at the Boston Comedy Club. It was a bringer show. I had to bring four people. I got six minutes, but I booked two nights in a row. I figured, I’m going to probably bomb my first night, so I’ll do two nights in a row. So even if I eat shit, I’ll have booked the second night, which will make me get up and do it again. So I go the first night, and I think I did twelve jokes, and I got decent laughs on half of them. I taped it. The next day I kept rewinding it and playing it; I couldn’t believe it that I got laughs from all these strangers—that it really worked. Jokes that I sat down and wrote. Six out of the twelve worked. I was so psyched. I went back to my place; I remember I was so excited that I couldn’t fall asleep. I’m a comedian!

Then the second night was at this place called Ye Olde Tripple Inn. It’s a bar, not a comedy club, not a bringer show, not a new talent night, just a back room of a bar. I did the same set, but now with confidence, because half of these jokes are working. And I died. I just totally bombed. Nothing. There was one guy, who was kind of crazy or something, who cackled through a lot of people’s sets. I taped that set too. When I listened to that, it’s just me telling the jokes, the silence, and then this one guy, laughing at my failure. I got offstage, and that night I couldn’t go to sleep either. I was confused and horrified. I couldn’t believe it. I was like, I don’t understand. I thought these were funny. That was just last night. The jokes worked. And then tonight, I died. They were definitely not funny jokes tonight. But last night, they were definitely funny. I felt it. I was like, Oh god, this is going to be hard.

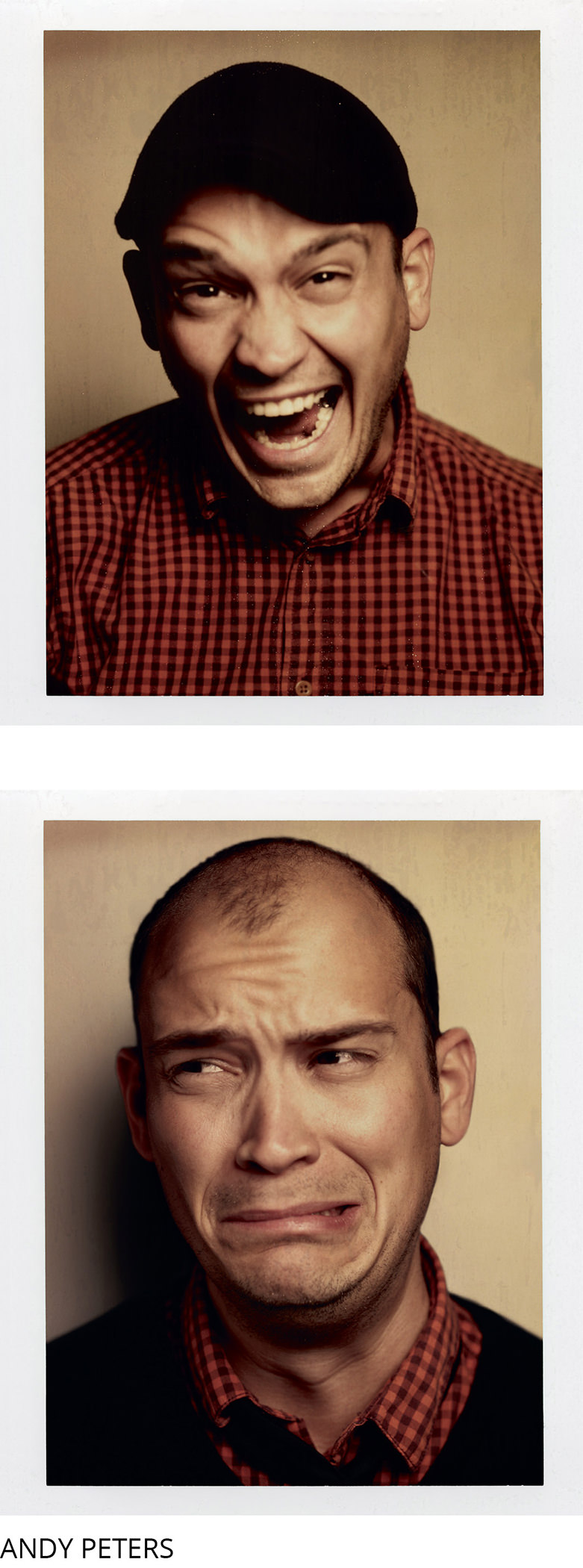

Andy Peters: I’m always envious of the comics that just did it: did the slow-burn start where they wrote first and tried open mics traditionally. Because the way I started was it was a contest. Three people showed up for this contest. We were the openers for Colin Quinn. Three scared college students doing stand-up for the first time ever in their lives. Long story short, I won. I think they just did it by audience applause.

It was not only my first time onstage; it was my first time meeting a stand-up comedian in person. I remember the producers were very casual about stuff, like, “You’re doing five minutes; we’re going to give you a two-minute light.” I was like, What does that mean? What do I do? Where do I stand? What do I do with my hands? I didn’t know how to interact with the audience; I didn’t know any of the stuff that you learn slowly over years of open mic-ing. It was such a crash course. Colin Quinn offered me gum; I remember that happening backstage.

MJ: How many people do you think were there?

AP: Probably four hundred people.

Moses Storm: I’m legitimately not good at anything else. Which kind of feels like a cop-out. But I never went to school. In my life.

I moved constantly growing up. So we started in Kalamazoo, Michigan, and then we lived in an old Greyhound bus, so we would spend six months at a time in a place, but a lot of time in Florida. A lot of time. Right when I turned eighteen, I moved down to L.A. as quick as possible. I was doing improv so I would get confident enough to do stand-up.

MJ: You knew you wanted to do stand-up.

MS: Yeah. The first time I did stand-up was at Hollywood Improv. The main room. This woman running a showcase show, I’d met her at an audition, and she was like, “I do a showcase show.”

MJ: You’d never done an open mic or anything?

MS: Never done an open mic or anything. This woman is a casting director that runs this showcase show? Sure, I’ll do that. Put together a five-minute set. It was the main room, Tuesday; it was sold out. I was onstage—it went very well for the first time. It was a very warm crowd. Then I was like, This is all I want to do.

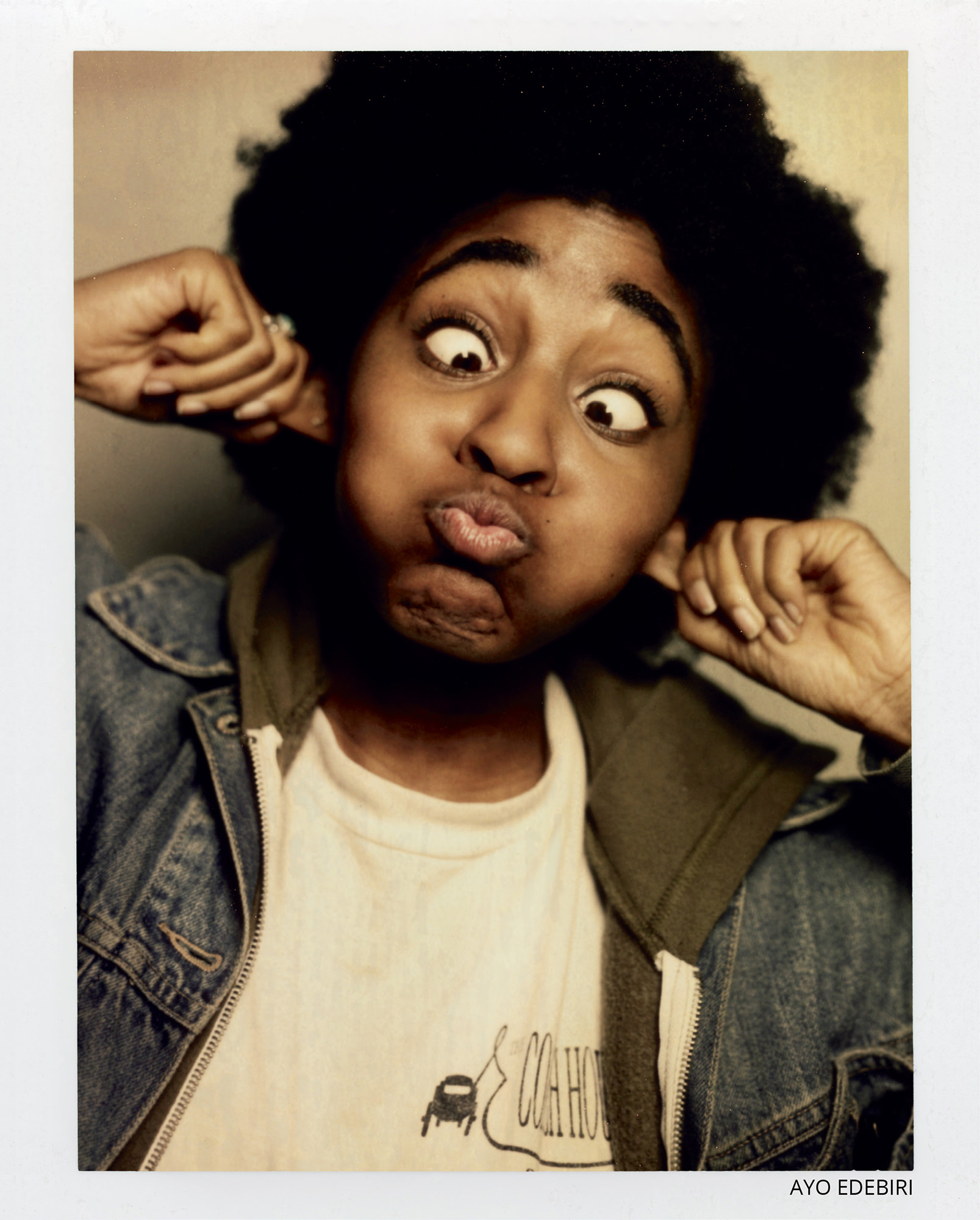

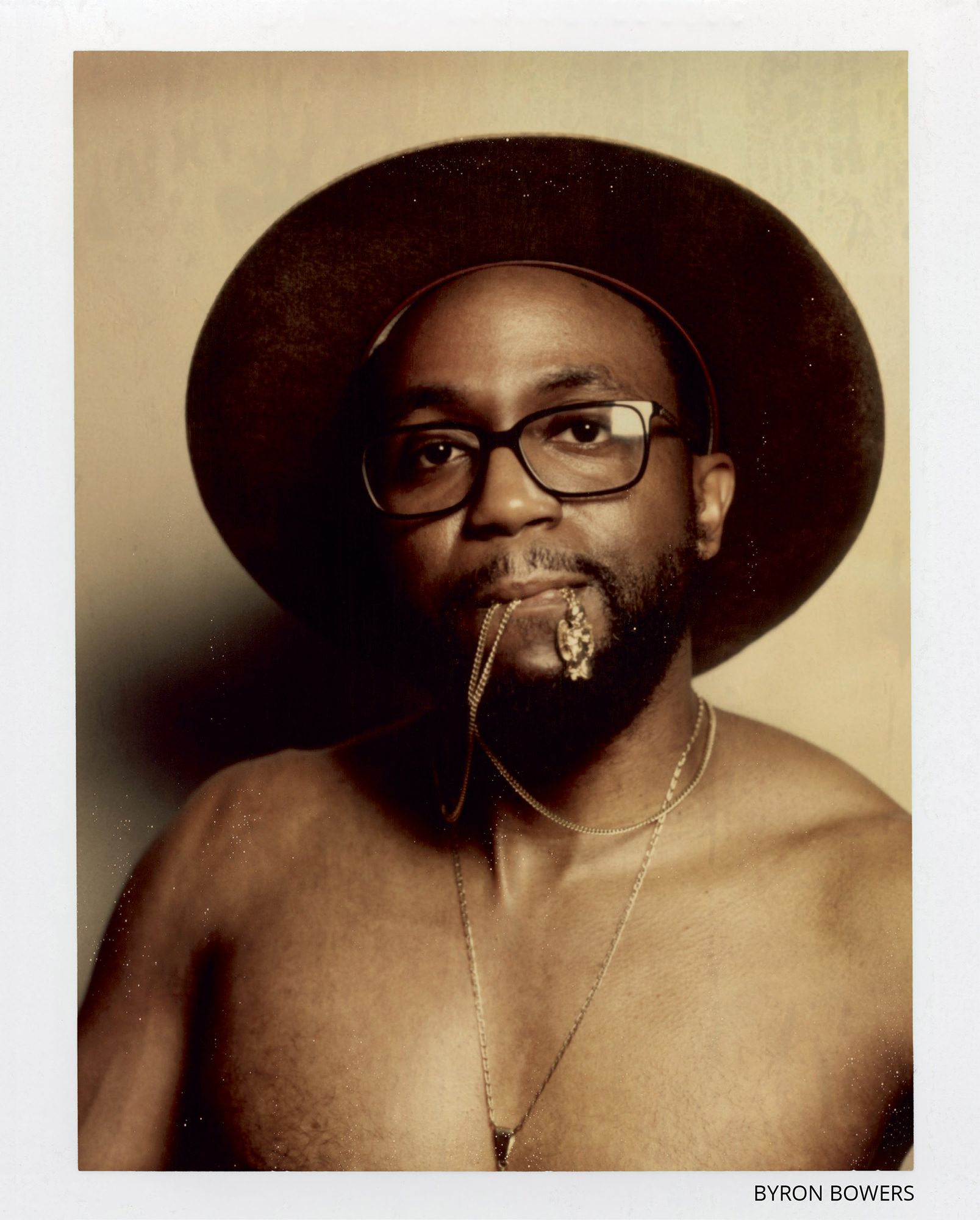

Byron Bowers: I started and quit the same day. It was Atlanta, Georgia, and it was amateur night at Uptown Comedy Corner. I’d never been in a club before, and me and a friend of mine went and signed up for amateur night just so we could get into the club for free. Mind you, I’d never written a joke before, so since I was lunchroom funny, I thought I could go up there and be funny. NOPE! I got booed by three hundred people. I quit that night for over a year and came back.

Dave Ross: I did stand-up maybe five times in 2006, and I would shake and cry.

MJ: In L.A.?

DR: In Fresno and then L.A. I have really bad stage fright.

(both laughing)

DR: Why are you laughing?

MJ: I just love that you have really bad stage fright. And you’re like, “Wanna know what I want to do with my life? I want to be onstage.”

DR: That’s a comedian in a nutshell, right? Though I will say this: obviously, it’s really, really sanded down, and I don’t experience it so much anymore, but one of the reasons was the stage fright. Because I’m also afraid of a lot of other things . . . I’m very open about it. And I wanted to conquer some fear, truly. In 2006 I was a radio DJ in Fresno. I don’t know if you know this, but radio is not a stable career path.

MJ: So you were like, you know what’s a better stable career?

Both: Stand-up!

Jackie Kashian: My name is Jackie Kashian, and I got into comedy by accident because that’s how you do it. In 1984, I believe. So Bill Kinison starts this club. It’s in the basement, it’s underneath this stupid pool hall bar, and I go and see stand-up comedy one night when I’m nineteen. The show was OK. I don’t remember the show. I remember Sam Kinison, because he was having a hard set, and he said something, and I was sitting right next to the stage. I just made some crack at him, because his timing was slightly off. I was so drunk it was ridiculous.

I didn’t understand . . . the drinking age was eighteen; I was nineteen. I didn’t know how to drink. I was hammered, and I heckled Sam. He mopped up the floor with me, but I was so drunk I didn’t stop. Because there’s nothing worse than a woman heckler. Whenever I’m being heckled now, I think of it as an indictment against my bad beginnings. I also think of it as proof positive that a woman heckler, even if you’re a woman comic, doesn’t matter; the audience for some reason is still on the side of the woman heckler. And they were completely on my side, and Sam couldn’t get out of it, and, finally, the manager [Bill] came over and told me to shut the fuck up: “You have to shut up. Open mic is on Sunday. If you want to talk anymore, you either have to leave or come back to open mic on Sunday.”

So three weeks later I came back to open mic. Sam Kinison was no longer there. Bill was still there.

Katherine Leon (producer): I kinda fell into it. I didn’t realize what I had gotten in to, to be honest. It was never really a thing that I saw as a job. I initially wanted to just [photograph] shows, but I was around enough that I started meeting performers and producers. I started shooting a few shows and would help out when I could, and, eventually, I tricked enough people into letting me try it out. I also maybe met everyone at the right time.

I’ve been a fan of comedy forever, but it really kicked in when I went to college and my best friend and I would just stay up talking about growing up watching SNL. I just knew things were funny—I didn’t really clock it as comedy. We would drive an hour almost every weekend and wait forever for UCB shows, and we felt like we were on some wait-list to be a part of a clubhouse. I just saw so many great things there, and I think I figured at that point that funny was maybe the only thing. If something was sad, it could also be funny. People playing to the height of their intelligence could be funny. Dumb and simple could also be really funny.

Anthony Jeselnik: I always loved comedy, but it didn’t seem like something you could really do. I’d had an internship in L.A. where I worked for a production company. I read scripts and answered phones. I was so dumb that I thought I knew L.A. I was like, I’m wired. I have this internship; I’ll come out here and get a job. I did not. I didn’t get a job at the place I interned at; I was just bumming around. After a year I was like, What do I want to do with my life? Stripping everything down, I thought, I loved comedy. Wouldn’t it be fun to be a joke writer? Write jokes on a late-night show, you’re writing every day with a bunch of other funny people. And one of my dad’s friends from college was the head writer for Jay Leno, so I met with him, and he told me, “Do stand-up, because that will help you get your voice out there, instead of writing jokes and sending them in, which people do, but it’s impossible. Do stand-up—it gets you out there more.”

At the time I was working at a Borders Books and Music. It was my first job out here. They had a bunch of books on how to do stand-up comedy. I bought the thinnest one. I still have it. It was by Greg Dean. I read the book, and I was like, OK, I kind of get it. I didn’t feel like I could just go to an open mic. Open mics seemed scary to me. So I took a class. At the back of the book, it says this guy teaches a class. I went, and it’s me and a bunch of hopeless older people who were like, Yeah, I’ll do stand-up? It’s the last thing they’re trying. This is the first thing I’m trying. At the end of the class you do a set. You do seven minutes.

MJ: Just in front of the class?

AJ: No, you go to the Comedy Store Belly Room and do a set. I had all my friends come. I thought I killed. I did compared to the other people.

MJ: Did you kill because you had all your friends?

AJ: No—I mean, that helped—it was because everyone was so bad. So nervous. In their forties. A twenty-two-year-old who was kind of funny . . . I went back and watched it.

MJ: Do you have the tape?

AJ: I have it somewhere. It’s VHS. It’s impossible to see. One of the jokes I used in my first set I ended up using in the Donald Trump roast. It was actually a good joke.

I went to the Ice House open mic like two weeks later. I was hungover. It was during the day. I just thought I’d repeat what I said at the Belly Room. And I bombed so hard that I had a panic attack. I remember going in the bathroom covered in sweat, like, What happened to me? What just happened? Then for months after that I would go to open mics and just sit in my car. I couldn’t get out of the car.

A few months after that, the movie Comedian with Jerry Seinfeld came out. He’d just done the one-hour for his whole life. That was his whole hour. So it was him going from scratch. It was so inspiring. Just keep performing and keep failing and eventually you’ll get something and keep writing. It clicked for me, and I started attacking open mics every night. The worse open mic, the better, for me. Just keep going, just keep writing . . . I eventually got away from anything the class taught me and just started writing jokes. I kept doing open mics, stayed away from the club scene entirely [because] you had to wait. I didn’t want to wait. I wanted to get onstage. Either to succeed or to fail.

Payman Benz (director): My path to being a filmmaker was through a love of comedy. As a kid, I loved movies, but I was madly in love with comedy. Executing comedy visually is what got me interested in being a filmmaker. Growing up, I wanted to be a performer, and slowly I realized that overseeing the comedy was more exciting to me than being the person who was getting the laughs. My voice was built through the thousands of hours of stand-up, sketch, TV, and movies that I’ve watched since being a kid.

Andy Kindler: I was a musician before I was a comedian, and I came up in Los Angeles to make a career—what I thought was going to be a career in music. I tried music for a few years. It was a rough period in my life; the early twenties are not as much fun as they say. Then I got into the mid-eighties, and a friend of mine, he was very funny . . . he said, “Hey, have you ever done comedy?” And then he said, “Oh, I’ll do it with you.” So I was in a duo for a couple of years, a regular, straight-up stand-up duo. It was really great because it’s very frightening to do stand-up as you know, so it made the start a little bit . . . We could both cry together. It made it easier to get into it.

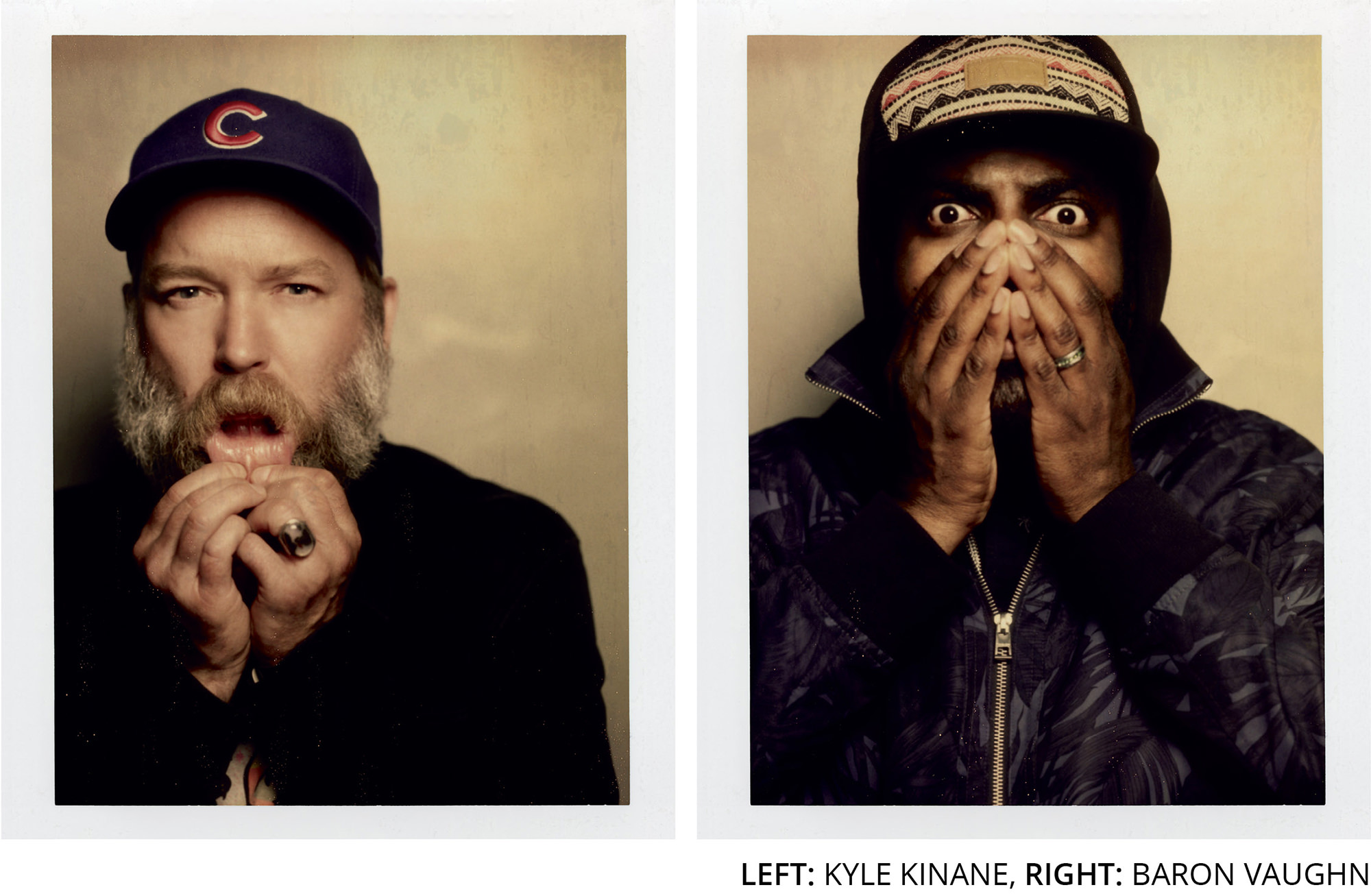

Baron Vaughn: It literally was always something I wanted to do. I didn’t understand that at the top of my consciousness, but deep down there was a part of me that felt I was a comedian.

People like Pryor or Eddie Murphy, Robin Williams, Steve Martin, people who are some of my favorite actors, were stand-up comics. I didn’t know that, and then I found it out, and it was like, They’re doing the thing I want to do. And so it wasn’t until I was in college that I was afforded the opportunity to actually go to an open mic. It was a two-person bringer . . . it was a five-minute set. The Boston comedy scene is so strange. There’s such a huge, strong, working-class group of people who are stand-ups, and then there are these heady, esoteric Emerson, Harvard, MIT students who want to do experimental stuff. You had Dan Mintz, Eugene Mirman who came out of Boston—these very heady comedians—but then it’s the same place that created Denis Leary and Marc Maron.

MJ: Dana came up on Boston too.

BV: Exactly. Dana Gould is the bridge in sort of a weird way. He’s got a working-class thing, but he’s also got this heady, esoteric, experimental thing at the exact same time. Some people consider him one of the fathers of quote-unquote “alternative comedy.” Boston is also the kind of place that creates Patrice O’Neal and Sam Jay. They’re from the same neighborhood. Boston has all those different kinds of people, if you will, in the same room. The variety of a show in Boston was always insane. Very interesting. The other thing that Boston puts into you is that you don’t really have the right to call yourself a stand-up—until you have been paid to do stand-up. Until then, you’re an open mic-er.

MJ: Interesting. Until someone gives you money to do stand-up.

BV: Until someone gives you money to do stand-up.

MJ: It doesn’t have to be a lot of money, just any money?

BV: Just any money. Now, to be fair, the fifth time I did stand-up, it was paid on the spot.

MJ: It sounds like you were a stand-up after your fifth time, then.

BV: I bombed.

MJ: Did they say it had to be a successful paid show?

BV: They didn’t.

Dana Gould: I came up in Boston in the mid-1980s at the peak of that comedy boom. And I was making, you know—I was a young guy, I was nineteen and twenty, and I had a driver’s license and a car, and I didn’t drink or do cocaine.

MJ: Congratulations.

DG: But I was one of the few people in Boston that didn’t, and I worked all the time because I could drive comics to gigs and they did not have to worry about me getting drunk and not being able to drive home or having to socially offer me blow. Which meant more for them. Because of that, I worked constantly.

MJ: That’s hilarious.

DG: I made a ton of cash because it was a cash business minus the cocaine. I was twenty years old living in a little neighborhood of Boston called the Student Ghetto. Janeane Garofalo lived across the street, and Tom Kenny, who is now the voice of SpongeBob, lived in my building. I moved to L.A. in ’89, and then right around 1991, Janeane Garofalo moved out, and that was right around the time that we started what became the alternative scene in L.A.

MJ: Truly the grandfather and grandmother—you and Janeane—of the independent comedy scene.

DG: It used to be mother and father.

My heart is for LA comedians.

—Steve Hernandez

Sean Patton: I told my dad I wanted to do comedy maybe a year before during the holidays while him and I were drunk at a Christmas party. I was like, “I think I want to try that,” and he was like, “Give it a go but it’s a”—he said something I still think about, like, you know—“That’s nothing but a lifetime of long shots.”

MJ: That’s such a deep, insightful quote.

SP: I remember him saying that and being like, “Nah, I don’t know. Whatever.” Now, eighteen years later, it’s like, Yeah, he’s right: it is a lifetime of long shots, but you just get better at aiming; you get better at taking the shot.