There is an eagle in me that wants to soar, and there is a hippopotamus in me that wants to wallow in the mud.

—Carl Sandburg

Some of my students smiled uncomfortably, others were startled, a few maintained stoic indifference. I walked around my class of thirty Ethiopian master’s degree students, placing a handful of dirt into each hand as I reiterated, “For dust you are and to dust you will return” (Gen. 3:19). We were discussing the nature of humanity, expressed in the Hebrew word adamah (“dust”) from which comes the proper name Adam. Adam is a creature of dust (Gen. 2:7). As they pondered that they were made of the same gritty substance as the dirt in their hands, I asked them how they felt. “Low,” “humble,” and “I don’t like to think this is what I am” were common answers. Many winced as I went on to cite that chimpanzees and humans share 96 percent of the same DNA.1 My dusty demonstration was intended to expand their imagination of what it means to be human.

We Westerners more often attend to the earthy side of our existence (“I’m only human”), but my Ethiopian students had been raised in a culture that denies the material and focuses more on the heavenly.2 To claim an identity as dust felt subliminally, if not consciously, repulsive to them.

Eagles and Hippos

We can name several tensions within our paradoxical humanity. First, we are creatures of dust, yet far more than material organisms. Blaise Pascal captures it in his epigram: “Man is only a reed, the weakest in nature, but he is a thinking reed.”3 The power of human intelligence has offered us technological mastery over our world never imagined by our ancestors. Yet our supercharged minds exist in bodies that are weak and fragile reeds. Infinitesimal viruses vanquish us. Chemical changes in our brains influence us far more than we may wish or often even realize.

With the animals, we share an existence influenced by hormones and instincts, yet unlike the animals, we can make conscious choices against our instincts, what theologians call “self-transcendence.”4 We are always in process, transcending our impulses, cultures, traditions, previous worldviews, and even (or especially) our pasts. It is impossible to imagine human life without this passion for growth and development, even though it can be tragically stunted, arrested, or denied. Creatures of dust we are, but being human also means our reach constantly exceeds our grasp.

Consciousness itself is another aspect of the human paradox. However adept computers become in mimicking human thought, their behavior can be explained in strictly physical terms. Might the same be true for us? As we discover and map more and more of our brain activity, will we conclude that our minds can be reduced to a complex machine, a biological computer? Or is human consciousness an indefinable extra that transcends physicality—something no computer will ever achieve, the “ghost in the machine”? A group of philosophers called “new mysterians” suggest that the more we enhance the power of computers, the more we realize the paradoxical anomaly of human consciousness, which is inexplicable in solely materialistic terms.5

The tension between freedom and necessity is a third aspect of the paradoxical human landscape. Eugene Peterson puts it well: “Freedom does not mean doing whatever pops into our heads, like flapping our arms and jumping off a bridge, expecting to soar lazily across the river. Freedom is, in fact, incomprehensible without necessity.”6 This dialectic of freedom within boundaries (what Peterson calls necessity) is at the heart of the human condition.

Humans have genuine freedom but not unconditional freedom. In fact, we truly experience our freedom only in relationship to boundaries, from the laws of gravity to the laws of society. Thus genuine human freedom is in constant tension with significant boundaries we cannot escape, nor wish to, for then our freedom would disappear as well. Advertising executives speak of the “paradox of choice,”7 having noticed we often freeze up when presented with no boundaries and too many choices: “Give us too little freedom and we’ll stand up to dictators in Cairo and fighter planes in Libya. Give us too much freedom (and too many channels), and we’ll sit in front of the TV, mindlessly flipping through our options, watching nothing.”8

Finally, humans grow as individuals within community, another paradox. Hermits and loners are the exceptions that prove the rule. Without community, we are less than what we might be, even at the most basic level: babies need cuddling by other humans for normal development. We remain, and always will be, “ourselves,” yet we discover much of who we are only through our interactions with parents, siblings, friends, peers, neighbors, and, more broadly, our tribe. While action films exalt the loner hero who turns his back on society, he (usually it’s a he) answers the call of community in its time of need. “No man is an island,” as John Donne famously declared. Most of us live most of the time in this paradoxical tension as individuals within community, neither swallowed up in a hive-like collective nor asserting a naked individuality.

Carl Sandburg elegantly reminds us, “There is an eagle in me that wants to soar, and there is a hippopotamus in me that wants to wallow in the mud.” To be human is to be intimately aware of both the wind in our faces as we soar and the mud underneath our fingernails as we wallow. We are paradoxical to the core: controlled by hormones and instincts yet making rational choices that transcend them, existing as material beings yet having a consciousness that materialism cannot explain, possessing freedom that is genuinely free only when contained by boundaries, and achieving individuality through the influence of communities.

A Monster beyond Understanding

Blaise Pascal, a mathematical genius (Pascal’s triangle) who was also a Christian mystic and apologist, is a worthy guide into this two-handled human paradox. In his collection of spiritual musings, Pensées, Pascal explains his approach to revealing the paradox of humanity: “If he vaunts himself, I abase him. If he abases himself, I vaunt him, and gainsay him always until he understands that he is a monster beyond understanding.”9

It is clear that Pascal is working with a two-handled paradox—two extremes that must be kept as far apart as possible. Pascal continually pushes and pulls the opposing handles. If his opponent vaunts himself by exulting in his human potential, Pascal abases him by pushing on the handle of human fallibility. If his opponent abases himself, Pascal vaunts him by pulling on the handle of human dignity. This push/pull motion, Pascal believes, is necessary to drill through the topsoil of easy platitudes. As he bores ever deeper, eventually his listener discovers the paradoxical nature of humanity: a monster beyond understanding. (Pascal intends “monster” not in the sense of something fearful but as something unusual or unnatural—that is, beyond comprehension.)

This is the tension of opposite extremes so masterfully described by G. K. Chesterton. On these big issues, Christian faith has always vehemently resisted any bleeding of one side into the other, the black and white of clear opposites coalescing into a dirty gray. Only the two colors kept coexistent but pure adequately convey the truth.

Swiss Christian psychologist Paul Tournier concludes that this dual human nature offers an “eternal mystery,” and comments, “This is what explains how man may appear so self-contradictory, how the best and worst are inextricably mixed together in him.”10 While no one would mistake me for a literary critic, I am not the first to notice that timeless literature often embodies this human paradox. Poor literature offers one-dimensional characters, stereotypical heroes and villains with obvious motives of good or evil. Better literature offers multidimensional characters struggling with their own mixed motives in ambiguous situations. Classic literature explicates, as Tournier says, the best and worst inextricably mixed together—good and evil, compassion and vengeance, altruism and selfishness—revealing it all in such a way that not only do we identify with the characters and the situations they face, but through them we better recognize our own inextricably mixed motives.

We have already seen that one of the attributes of mystery is conscious ignorance: we increase our understanding that there are things beyond our understanding, thus becoming more conscious of our own ignorance. Pascal uses the two-handled paradox to usher us into this mystery of our own humanity, which is beyond our understanding. How might the stark black-and-white clarity of the two-handled paradox lead us with awe and silence into the presence of this mystery?

Never Too High or Too Low

Some of our contemporaries regard human life as meaningless; we are insignificant beings adrift on a tiny planet in a backwater galaxy of a vast universe. Biblical theology agrees: “When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is mankind that you are mindful of them, human beings that you care for them?” (Ps. 8:3–4). “Dust you are and to dust you will return” (Gen. 3:19). “The life of mortals is like grass, they flourish like a flower of the field; the wind blows over it and it is gone, and its place remembers it no more” (Ps. 103:15–16).

But the Bible goes far beyond despairing existentialists and suggests that while human life is not meaningless, it is evil at its core. The human gene pool is irretrievably contaminated by original sin. All human pretensions to righteousness are “filthy rags” (Isa. 64:6). Human beings are sinners capable of outwardly brutal atrocities and inwardly rampant selfishness. Human life can be not only meaningless but depraved.

The opposite intellectual current in some quarters views human beings as the fountainhead of all value and meaning (famously expressed by Ayn Rand).11 The Bible again goes this view one better: “You have made them [humans] a little lower than the angels and crowned them with glory and honor. You made them rulers over the works of your hands; you put everything under their feet” (Ps. 8:5–6). Human beings have inestimable value and purpose because they are made in God’s image; they are the pinnacle of God’s marvelous creation (Gen. 1:26). Ever since God walked with Adam as one friend with another in the cool of the garden (Gen. 3:8), no religion has held such an exalted view of human potential.

Chesterton reminds us that to adequately describe humanity, we must contradict ourselves: “In so far as I am Man, I am the chief of creatures. In so far as I am a man, I am the chief of sinners.”12 So also C. S. Lewis in the Chronicles of Narnia, when Aslan addresses Peter, Edmund, Susan, and Lucy: “ ‘You come of the Lord Adam and the Lady Eve,’ said Aslan. ‘And that is both honor enough to erect the head of the poorest beggar, and shame enough to bow the shoulders of the greatest emperor on earth.’ ”13

Contradictions abound. Humanity’s incredible potential for evil is matched by an opposing potential for good. With the same human tongue, we bless God and curse people (James 3:9). Mother Teresa and Adolph Hitler inhabit the same skin.

If anything, this contradiction is heightened when we turn to God’s own people. Venerable Old Testament commentator Gerhard von Rad remarks concerning Abraham, “The bearer of the promise himself [is] the greatest enemy of the promise; for [the promise’s] greatest threat comes from him.”14 Abraham bears the promise that God will create from him a people as limitless as the sand on the seashore; yet Abraham is also the greatest enemy of that promise by trying to achieve through human machinations God’s promised son and heir. If Abraham is the headliner for this kind of paradoxical push/pull in the Old Testament, surely Peter plays a similar role in the Gospels—both the rock and a stumbling block to Jesus’ mission (Matt. 16:18, 23). As goes paradoxical Peter, declares commentator F. Dale Bruner, so over the centuries we see the church itself: “The church is both Christ’s main instrument and his main impediment.”15

Pascal, our guide into the human paradox, sums it up succinctly: “Men never do evil so completely and cheerfully as when they do it from religious conviction.”16 From the Pharisees’ persecution of Jesus, to Saul’s persecution of the earliest Christians, to centuries of wars pitting Protestants against Catholics, history offers abundant evidence.

How might keeping these high and low views of humanity separate and distinct help us? First, accepting that life is paradoxical is a means of grace. Trappist monk Thomas Merton writes, “It is in the paradox itself, the paradox which was and is still a source of insecurity, that I have come to find the greatest security.”17 He goes on to explain why his paradoxical humanity is a means of God’s grace: “I have become convinced that the very contradictions in my life are in some ways signs of God’s mercy to me; if only because someone so complicated and so prone to confusion and self-defeat could hardly survive for long without special mercy.”18

Our goal has consistently been to look through the window of paradox to see what it reveals, especially about God. As Merton looks through his own paradoxical humanity, he sees a God who, far from being put off by it, uses paradox as a channel of grace and mercy. Might we miss this grace and mercy if we succumb to either/or thinking and embrace only one side of ourselves, either the dusty or the heavenly?

Second, either/or thinking is often the strategy of Christianity’s modern critics. G. K. Chesterton notes, “One rationalist had hardly done calling Christianity a nightmare before another began calling it a fool’s paradise. . . . The state of the Christian could not be at once so comfortable that he was a coward to cling to it, and so uncomfortable that he was a fool to stand it.”19 Despairing existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre judge Christianity to be a nightmare, lacking all human dignity and freedom; confident humanists like Richard Dawkins judge Christianity to be a head-in-the-sand fool’s paradise, lacking all intellectual rigor.

However, when the two sides of paradoxical humanity are kept crisp and sharp, as G. K. Chesterton advises, the Christian worldview is at the same time more despairingly negative and more confidently positive than any alternative the world offers. Humanity biblically understood is ultimately more balanced, more able to assimilate disparate viewpoints, and more comprehensive of reality than either despairing existentialism or confident humanism. As Pascal knew, herein abides Christianity’s greatness.

Third, when we absorb both high and low views of humanity into our spiritual bloodstream, it makes redemption more meaningful. As a young child saying my prayers at night, I remember asking my mother, “Am I a Christian?” and she replied, “Yes, Rich, you’re a good boy.” I grew up in a church that did not talk much about sin or the low views of humanity. A Christian was anyone who tried to live a good life and follow the Golden Rule. This background did not prepare me for the evil I eventually saw in myself, especially during angry conflicts that grew to borderline hatred of my father. It was not until I heard some ’70s Jesus Freaks preaching on my campus that I realized what incredible good news owning a low view of my sinful self could be; it opened me up to the forgiveness and new life Jesus offered me.

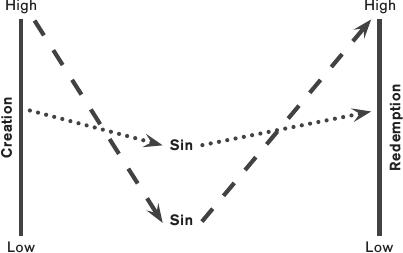

Since then, my experience as both pastor and teacher of theology has convinced me that keeping the highs and lows of humanity crisp and distinct makes for a more robust view of Christ’s redemption. Consider figure 1, which plots high and low views of creation, sin, and redemption.

When we have a lower view of the glory of humanity, it is often accompanied by a much less drastic view of sin, which usually then leads to a lower view of redemption (dotted line). This creates a relatively flat line from creation to redemption (and unfortunately brings to mind Jesus’ words in Revelation 3:16: “Because you are lukewarm—neither hot nor cold—I am about to spit you out of my mouth”).

FIGURE 1

However, when we have a high view of human beings as the pinnacle of creation with whom God walked in the garden, this tends to correspond with a precipitously lower view of sin as the loss of this intimate relationship with God, resulting in humanity’s being warped away from God’s good creation in every conceivable way. Such a lower view consequently requires a much higher view of redemption to achieve the return of humanity to its former lofty position (dashed line). The much steeper lines in this scenario better correspond with the biblical view of humanity, which is both extremely high and extremely low. Just as our celebration of Easter depends on how deeply we comprehend and experience Good Friday, so our gratitude for our redemption in Christ seems to track with how deeply we comprehend these highs and lows of our humanity. When I understood that being a Christian was far different from being a “good boy,” I was ready to claim the redemption I had heard about occasionally in church but never thought I needed myself.

Finally, a fourth consequence of this “high/low” view of humanity is the ability to appreciate human culture without turning it into an idol. Some Christians focus so completely on the lows of human depravity that they are incapable of marveling at all that humanity has achieved. Yes, the church has always been corrupt, yet it has produced some of the most beautiful buildings, music, and art of the last thousand years. Yes, Isaiah is correct that “all our righteous acts are like filthy rags; we all shrivel up like a leaf, and like the wind our sins sweep us away” (Isa. 64:6). But in a well-intentioned effort to keep humanity in its place, we can miss the glory present in art, literature, music, science—indeed, any human endeavor.

Human achievements—whether by Christians or non-Christians—ultimately give glory back to the God who created us with the capacity for this creative self-transcendence. We create because we are made in the image of our Creator. When we understand our “high/low” paradoxical nature, we Christians, of all people, can most genuinely revel in the cultural achievements of our fellows yet still worship the God who planted the creative impulse within us.

Speaking of the human paradox, C. S. Lewis writes, “Our own composite existence is not the sheer anomaly it might seem to be, but a faint image of the Divine Incarnation itself—the same theme in a very minor key.”20 If Lewis is right, a great mystery is indeed afoot: humanity is a faint echo of the greatest paradox of all.

Reflection Questions

1. In your experience of human nature, do your first thoughts naturally tend more toward the positive (“vaunts himself”) or the negative (“abases himself”)?

2. What experiences have you had encountering the soaring eagle and wallowing hippo in your nature? Is it positive or negative to find both within you?

3. Do you agree that the paradoxical Christian view of humanity is superior to viewpoints that stress only high or low views of human life?

4. “LORD, what are human beings that you care for them, mere mortals that you think of them? They are like a breath; their days are like a fleeting shadow” (Ps. 144:3–4). How does this verse express both the value and the weakness of human beings?