Please turn the page for an intimate conversation

with Kim Michele Richardson about

GodPretty in the Tobacco Field.

with Kim Michele Richardson about

GodPretty in the Tobacco Field.

GodPretty is a phrase that I made up to show starkness in the brutal and beautiful land and its people and mysteries. The term is necessarily paternalistic in the book and means to the one character, Gunnar, to keep a good and Godly soul if you are of a religious nature as he is. To Gunnar, GodPretty is applicable to females, while a male would be “righteous.” Gunnar uses my coined phrase GodPretty to push his strict moral code on his fifteen-year-old niece, RubyLyn. It came out of the uncle’s yearnings for his niece—wanting her to be pretty and pretty in the eyes of the Lord, so God would protect her when he no longer could, so that she would have a good life and be smiled upon by others not only because she’d be pretty but because her soul would shine, too. From the opening scene you can feel the title, the contrast with the ugly tobacco fields, giving a foreboding presence. Gunnar controls RubyLyn with this phrase, his large presence, big hands, hard ways of talking, acting. So when he punishes her, she can’t resist, can’t fight, until one day . . .

I wanted to write a tale of tender love and loss, the importance of land, oppression of Appalachian women in the ’60s, and use a unique place. More than anything it was my hope to weave the theme of poverty’s oppression on women and portray the consequences. I do this with the four Stump girls, RubyLyn, and the rest of the women in the fictional town of Nameless, Kentucky. The girls’ actions show how the crushing poverty knows no gender, age, or boundaries, and how it becomes a scatterbomb, harming the person, the family, friends, and everyone in larger society—how it affects learning, choices, and notions of self-worth on life’s whole journey. And again, in GodPretty we visit racial strife and examine difficult history from this timely subject. We also look at the last public hanging that took place in Kentucky (Rainey Bethea, August 14, 1936, Owensboro, KY).

I hoped to explore Appalachia’s history, back to when President Johnson and the First Lady, Lady Bird, surprised the world and visited the tiny eastern Kentucky town Inez in 1964. Bearing witness right down to the hand-hewn porch of Tom Fletcher that Johnson squatted on, to the color of the First Lady’s coat, and to the reminder of the newly minted coin commemorating President Kennedy. I wanted the reader to feel that hope and loss through the eyes of a 10-year-old RubyLyn.

GodPretty in the Tobacco Field is rich with music. I love music, particularly the violin. Though I can’t play a lick, my daughter started playing strings when she was three, and my husband plays the clarinet and piano. And we have a set of simple hand-carved wooden musical spoons like those mentioned in the book.

The people of Appalachia are born to music, much of it still lost to time’s passing, and I pull some lost treasures into the novel like this one I found from the National Jukebox in the Library of Congress: “Sweet Kentucky Lady” (http://www.loc.gov/jukebox/recordings/detail/id/913).

Art is important to RubyLyn, and the papers she uses for her fortune-tellers are made from the pulp of the tobacco stalk and have her intricate drawings of pastoral scenes, portraits, and her fantasy cityscapes.

The land is a vital theme, too. It is how we live, breathe. When I was young, I worked in a tobacco field one summer. I hated it. Now my family and I grow vegetables and fruit on our small farm to give to the elderly. But last summer I grew a tiny patch of tobacco to visit that childhood setting again for my characters.

You’ll visit a State Fair in the novel, icons of summer and youth—and look at the Future Farmers of America club before it allowed female membership, the sweeping change it made in 1969, and the important role the youth organization has for our earth and our future farmers.

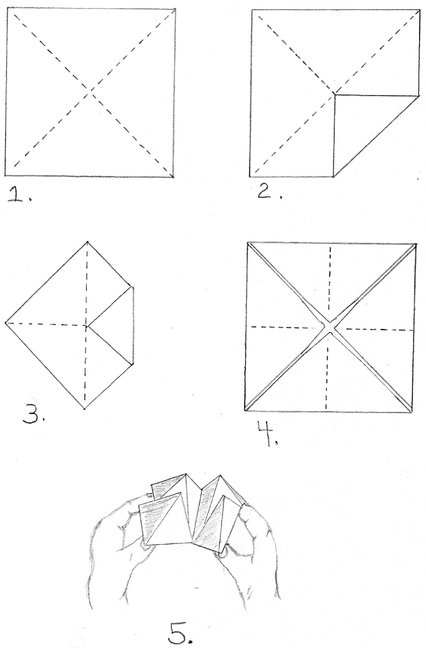

The paper RubyLyn uses for her fortune-tellers is made from the pulp of the tobacco stalk. She draws intricate scenes of rural life, portraits, and fantasy cityscapes. But you don’t have to grow tobacco and produce your own pulp. You can have one by cutting out any piece of paper and following these simple instructions below. Decorate your fortune-teller any way you like.

To see other readers’ fortune-tellers like the ones RubyLyn makes, please visit my Facebook page and post your photos:

I am excited to see your works of art!

INSTRUCTIONS

1. Cut out square and fold over diagonally on both dotted lines.

2. Flatten paper and fold all four corners to the center and press in creases.

3. Unfold, flip paper over, and fold four corners to center dotted lines.

4. Fold vertically and then horizontally on dotted lines.

5. Slip thumbs and forefingers into slots.