12

Night and Day Arnhem 17–18 September

A Dutch diarist, whose house overlooked the approaches to the great Arnhem road bridge, guessed that the British must be close when a flare went up. A German sentry could be heard calling out in panic: ‘Ich bin ganz allein!’ – ‘I am all alone!’

The leading platoon of Frost’s 2nd Battalion reached the Arnhem road bridge at about 20.00 hours, soon after night had fallen. Major Digby Tatham-Warter kept his men of A Company hidden under it, allowing German traffic to continue. He sent two platoons out to the sides to prepare some of the nearby houses for defence. Sergeants and corporals knocked respectfully on doors, explained what they had to do and recommended that the family sought shelter elsewhere to avoid the coming battle. Not surprisingly, most were very upset. Their spotless houses were rapidly transformed for fighting. Baths and basins were filled to ensure a supply of water, because the electricity was bound to go off again. Curtains, blinds and anything flammable were ripped down, furniture moved to make firing positions and windows smashed out to reduce casualties from flying glass. The battalion padre, Father Bernard Egan, who was helping these paratroopers, confessed to deriving ‘somewhat of an unholy glee from pitching a chair through a window, knowing full well there were no police around to reprimand me’.

As darkness fell, Lieutenant Colonel Frost remembered the German army saying that ‘Night is the friend of no man,’ yet it certainly seemed to be helping his paratroopers. He caught up with the rest of A Company lying quietly on the embankment of the bridge, while Germans still passed back and forth. Frost probably arrived about an hour after most of Gräbner’s reconnaissance battalion of the 9th SS Hohenstaufen stormed south over it towards Nijmegen on Bittrich’s order. Yet Standartenführer Harzer, the Hohenstaufen divisional commander, had overlooked the second part of Bittrich’s instructions – to secure the bridge itself. Only a handful of men from the original guard detachment remained on the bridge.

Frost had been disappointed to find that the pontoon bridge they had passed a kilometre back had been dismantled. After the loss of the railway bridge in the explosion, it was now impossible to send men across to seize the south end of the road bridge except in boats, but groups sent off in search of them had no luck. Tatham-Warter had been waiting until they could rush both ends at the same time, but they could delay no longer. Lieutenant John Grayburn’s platoon was chosen for the task. Grayburn, who won the Victoria Cross for this action, seems to have been determined to display conspicuous gallantry. He led his men up the steps on to the roadway. Sticking close to the massive steel girders on each side, his platoon charged against the fire of an armoured car and 20mm twin flak guns. Grayburn was hit in the shoulder and other men were wounded, so they had to withdraw.

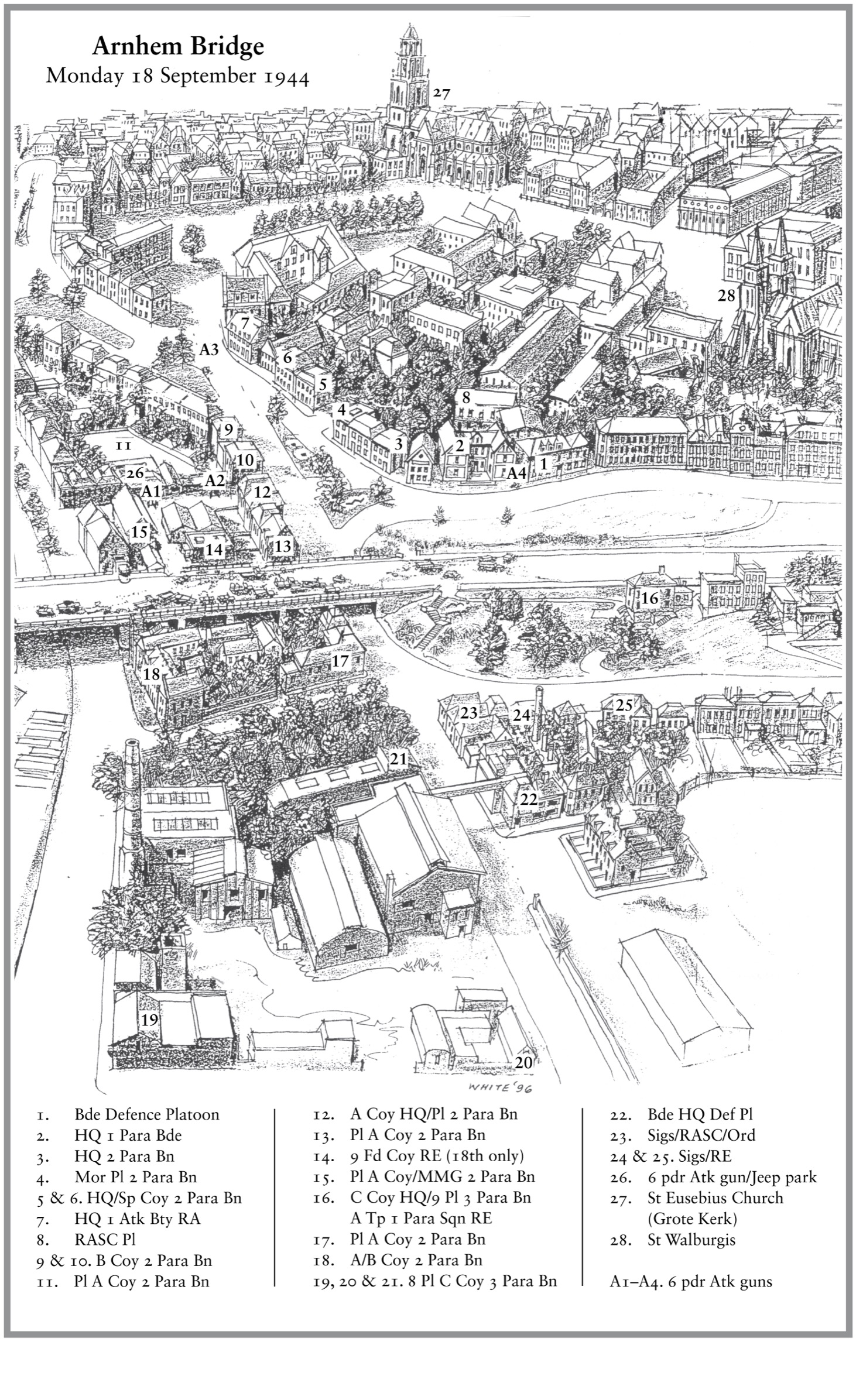

During this first attempt to secure the bridge, more and more houses overlooking the ramp and the approaches were occupied. (See plan.) The Jeeps and the 6-pounder anti-tank guns were at first parked in a space concealed by houses west of the bridge. The headquarters and defence platoon of the 1st Parachute Brigade (minus Brigadier Lathbury who was still with General Urquhart and the 3rd Battalion on the far side of Oosterbeek) took over buildings on the west side of the ramp next to Frost’s headquarters.

Major Freddie Gough of the reconnaissance squadron arrived with his headquarters in three Jeeps and reported to Frost just as a second attempt was made to seize the bridge. To deal with a pillbox on the side of the bridge, another platoon and an airborne engineer with a flamethrower got into position. But the operator’s number two tapped him on the shoulder just as he was about to fire, and he jerked back in surprise. As a result the spurt of flame went over the top of the pillbox and hit a pair of wooden shacks just behind. They must have contained ammunition, fuel and dynamite because an almighty explosion and fireball followed. It looked as if they had set the whole bridge on fire, which produced some sarcastic comments about capturing the bridge and not destroying it. There was one advantage. Three trucks full of German troops approached over the bridge, and as their drivers tried to manoeuvre past the fires, Frost’s paratroopers began shooting. Soon all three vehicles were blazing, as well as several of the unfortunate soldiers, who were cut down.

Remembering how the Germans had blown up the railway bridge in front of their noses, Frost was still concerned that the great road bridge could also be brought down, but a Royal Engineer officer assured him that the heat from the fires would have destroyed the wires leading to any explosive charges. Even so, Frost spent a restless night. The big attack would come in the morning, and despite the urgent efforts of the signallers, they were not yet in touch with divisional headquarters or the other battalions. The reasons for the 1st Airborne Division’s disastrous communications have still not yet been fully explained, and perhaps never will be. They include a problem of terrain, with woods and buildings, insufficiently powerful sets, run-down batteries and, in the case of some sets, the wrong crystals being issued.

Assessing the perimeter they needed to hold around the northern end of the road bridge, Frost wished he still had C Company under Major Dover, but his signaller could not make radio contact to recall them. After the railway bridge had been blown up, C Company had set off for its secondary objective, the German headquarters in Nieuwe Plein. As it passed the St Elisabeth Hospital, Dover’s company surprised thirty German soldiers climbing down from two buses. They killed most of them in a one-sided firefight and captured five. But as they proceeded they started to come up against soldiers and vehicles of what soon became the Kampfgruppe Brinkmann, based on the reconnaissance battalion of the SS Frundsberg. Even though C Company managed to knock out an armoured car with a PIAT anti-tank launcher, they were forced to pull back. They were eventually surrounded, yet managed to hold out for another sixteen hours until their ammunition was exhausted.

As if to balance the loss of Frost’s C Company, an unexpected reinforcement arrived in the form of Major Lewis’s C Company of the 3rd Battalion, the one which had made its way into Arnhem along the railway track. As they crept down towards the road bridge through the centre of the city, they had a chaotic and murderous encounter in the dark streets.

A unit of Reichsarbeitsdienst teenagers from a heavy flak detachment had been waiting in Arnhem station to return to Germany. Late that afternoon on learning of the airborne landings, their commander, Hauptmann Rudolph Mayer, had gone to the town commandant’s office to find out what they should do. He returned to announce that they would be armed and that they would be coming under SS command. The boys were marched to a nearby barracks where they were issued with old carbines. The bolts did not work properly and the only way to open the chamber was to knock them against something hard. ‘Their morale was not high, but it really hit the bottom when they saw these old guns,’ one of their officers recorded. That evening they had still received no orders and no food. In fact they had not eaten for nearly forty-eight hours, because of the delay at the station.

As dusk fell, SS-Obersturmführer Harder appeared and announced that they were now part of Kampfgruppe Brinkmann from the 10th SS Panzer-Division Frundsberg. They would attack from the town centre towards the Rhine. In the pitch dark, they became aware of other soldiers who they assumed were also part of the same Kampfgruppe. Suddenly a British paratrooper yelled: ‘Germans!’ Everyone began firing in panic. The wild scene was illuminated for odd moments by flashes or explosions. At close quarters, British Sten guns killed more efficiently than the antiquated bolt-action rifles issued to the RAD teenagers. Almost half of Mayer’s boys were killed and the rest must have been traumatized, yet Lewis’s company also lost a platoon commander and a sergeant, and a third of his men were captured by SS panzergrenadiers.

The remnants of this 3rd Battalion company joined the engineer troop led by Captain Mackay in two buildings of the Van Limburg Stirum School on the east side of the bridge ramp. Not long afterwards, panzergrenadiers, either from the Kampfgruppe Brinkmann or the SS Battalion Euling, crept up and tossed grenades through the windows of the house furthest from the bridge.

‘We fought hand to hand in the rooms,’ Mackay wrote. ‘One of them brought a Spandau [MG-42] and poked it right through the window spraying the room. I was standing there with my .45 and just pushed it in his mouth and pulled the trigger. It blew his head off, or all that was not held on by his chin strap. I grabbed the Spandau and turned it on the Germans outside.’ In other parts of the building there was fighting with fists, boots, rifle butts and bayonets before the Germans were dislodged. Mackay recognized that the smaller of the two buildings on the north side was far too vulnerable, with bushes in which German attackers could hide, so he decided to abandon the house. They pulled out their wounded, whom they had to haul over a two-metre wall with Mackay straddling it as each man was handed up to him.

Altogether Frost’s force was probably more than 700 strong with all of the attached arms and services, ranging from the Royal Engineers to the Royal Army Ordnance Corps. In brigade headquarters, the signallers installed themselves in the roof, having removed a few tiles for their antennae. They spent the night trying to make contact with divisional headquarters and the other two battalions, sending messages that the 2nd Battalion was at the bridge and urgently needed reinforcements.

Major Dennis Munford of the Light Regiment Royal Artillery knew that without a working radio set he could not direct fire support from their pack howitzers taking position around Oosterbeek church. He and another officer therefore decided to drive back that night through German lines in Jeeps to Wolfheze. They retuned their No. 22 Sets there, collected more batteries, reported on the situation at the bridge and drove back once more through German lines. Only Munford’s Jeep got through. The other officer received a serious stomach wound and was captured. At dawn, Munford would range in the 75mm howitzers on the enemy’s likely avenues of approach both from the south end and around the northern perimeter. One of the inhabitants in a house very close to the church and the gun line recounted how a British gunner knocked politely at their door, urging them not to be frightened when the guns began firing. ‘When you hear a boom and a whistle it is ours,’ he explained. ‘When you hear a whistle and bang it is one of theirs.’

Lieutenant Colonel Dobie with his 1st Battalion, having abandoned the attempt to follow the northern route into Arnhem, was determined to get to the bridge to support Frost after his radio operator had picked up one of the messages. They made their way south during that first night, until Dobie decided to take the Utrechtseweg in the middle as a shorter route. But when his lead company reached the railway embankment east of Oosterbeek they came up against Möller’s 9th SS Pioneer Battalion. Möller himself wrote melodramatically, ‘With the coming of the dawn, the dance began . . . It was a battle man against man – the “Red Devils” against the “Men in Black”, elite against elite.’ The 1st Battalion could not get through. Still missing one company after the clash with the Luftwaffe Alarmeinheit and now weakened by further casualties, the battalion zigzagged down to follow the southern road close to the river. Dobie’s men were tired, having had very little rest.

Lieutenant Colonel Fitch’s 3rd Battalion, which had halted for much of the night near the Hotel Hartenstein on the western side of Oosterbeek, set off again at 04.30 hours. Fitch also chose the southern route. Both Brigadier Lathbury and Major General Urquhart carried on forward with the lead company: an unwise surfeit of senior officers so close to the front. The battalion had to pass through a wooded area where German riflemen had climbed trees. These harassing attacks delayed the rear half of the two-kilometre-long column. An inhabitant of Oosterbeek was thrilled to see a British soldier kill a sniper, ‘just like shooting a crow’.

Further delays occurred as they advanced cautiously at dawn through Oosterbeek. Locals would throw open their windows and call ‘Good morning!’ across the street. ‘Good morning to you,’ came the unenthusiastic reply to their presence being revealed. Soon families were pouring out into the street, some wearing a coat thrown over their pyjamas or nightdress, to offer tomatoes, pears and apples from their gardens and cups of coffee or tea.

These distractions, after the shooting, delayed the rear of the battalion, and they lost touch with the vanguard, which by then had passed under the railway bridge a kilometre east of Oosterbeek church. To confuse matters even more, Dobie’s 1st Battalion also joined the southern road, mixing in with the rear part of the 3rd Battalion, which did not follow the route taken by the leading company with Lathbury and Urquhart. This vanguard had wasted precious time waiting for the other companies to catch up. On continuing the advance, they came up against the southern end of Spindler’s second Sperrlinie around the St Elisabeth Hospital, some two kilometres short of the road bridge. By now Spindler’s blocking force was being strengthened with self-propelled assault guns (often misleadingly described as tanks in British accounts). The 1st Battalion, meanwhile, soon found itself under fire from the high ground of Den Brink. The planners back in England had failed to see the danger on the map. The two roads from the west reached western Arnhem on the side of a hill between the railway line and the river. This provided an ideal choke point to slow or halt the British advance.

The Germans of course suffered from confusion too. Presumably as the result of a radio message from Gräbner’s reconnaissance force charging south the previous evening, Model’s Army Group B had reported at 20.00 hours ‘Arnhem–Nijmegen road free of enemy. Arnhem Nijmegen bridges in German hands.’ But not long afterwards two German women telephonists in the Arnhem exchange warned Bittrich that British paratroopers had secured the northern end of the road bridge, and they proceeded to pass information throughout the night. Bittrich awarded them both the Iron Cross after the battle. He went to Harzer’s command post in the early morning in an angry mood, because Gräbner had ignored his ‘order that the bridge be taken and firmly held’.*

Model also appeared at Harzer’s command post set up in Generalmajor Kussin’s headquarters in north Arnhem. There was low cloud that day, he observed, which should at least frustrate the Allied air forces. He told Harzer that the Heavy Panzer Battalion 503 with Mark VI Royal Tigers was being brought across Germany by Blitztransport from Königsbrück near Dresden. This meant that the Reichsbahn had to clear every line and every train, short of the Führer’s personal Sonderzug, out of the way. Another fourteen Tiger Mark VI tanks from Heavy Panzer Battalion 506 at Paderborn were already on their way. Their crews had been wakened at 00.30 hours in their barracks at Sennelager, and by 08.00 hours every tank had been loaded on to railway flat-cars. Model also announced that he would have the water supplies cut off to Oosterbeek, as that was where the bulk of the British would be forced to withdraw. Although Model still refused Bittrich’s requests to blow the bridge at Nijmegen, he sent a curt order by teleprinter later in the morning: ‘Destruction of Rotterdam and Amsterdam harbours to proceed’. This was one of the first stages of German retaliation for the rail strike to help the Allies.

All through the night, Model’s staff had been ordering in reinforcements towards Arnhem, using the town of Bocholt as railhead. The 280th Assault Gun Brigade, en route from Denmark to Aachen, was diverted to Arnhem. Other units included three battalions of around 600 men each; nine Alarmeinheiten of scratch units totalling 1,400 men; two panzerjäger companies of tank destroyers from Herford; six motorized Luftwaffe companies totalling 1,500 men; and a Flakkampfgruppe made up of ten batteries, with a total of thirty-six 88m guns and thirty-nine 20mm guns. They were ‘temporarily motorized’ which meant that civilian tractors and trucks were used to tow them. The 20mm light flak guns were sent forward to the landing zones to take on any more airborne lifts or drops.

As these units reached the Arnhem area, Bittrich distributed them between the two divisions. To Harzer he allocated a police battalion from Apeldoorn, a veteran reserve battalion from Hoogeveen and a flak brigade due to arrive a little later. These additions would bring Harzer’s Hohenstaufen up to nearly 5,000 men. Harmel’s Frundsberg would receive the company of Tiger Mark VI tanks from Paderborn, although because of breakdowns only three would arrive; an SS-Werferabteilung (a heavy mortar battalion); an engineer battalion with flamethrowers brought in from Glogau, and a panzergrenadier training and replacement battalion, arriving from Emmerich.

This last unit did not sound very promising. Many of its men had suffered amputations, while its commander Major Hans-Peter Knaust led his battalion on crutches. But Knaust, who had lost a leg in the battle for Moscow when with the 6th Panzer-Division, was a formidable leader. Without bothering to consult the local authorities, he ordered his men to seize the fuel reserves at the town of Bocholt to fill their tanks. Going ahead of his men in the only half-track his Kampfgruppe had been allowed, he reported to Bittrich’s headquarters at 02.00 that morning. Bittrich’s SS aide announced Knaust rather disparagingly as ‘someone from the army’. Bittrich, who in any case enjoyed good relations with the regular army, was certainly pleased to see him. He needed every unit possible, and Knaust, with his four panzergrenadier companies, would also receive a platoon of assault guns and a company of seven Mark III and eight Mark IV tanks from a driver-training school in Bielefeld.

Model’s plan was not just to block the rest of the 1st Airborne Division from reaching the Arnhem road bridge, it was to crush it between two forces. He had sent instructions during the night by teleprinter to General Christiansen, the Wehrmacht commander-in-chief Netherlands. His forces under General von Tettau were to attack the ‘air-landed enemy from the west and north-west’ and link up with II SS Panzer Corps on the northern side. Tettau had done little on 17 September, apart from telling Sturmbannführer Helle to take his SS Wachbataillon from Amersfoort concentration camp to Ede. Helle, no doubt regretting the abrupt farewell to his mistress, somehow imagined that the British were advancing west towards him, when they were pushing east to Arnhem. His guard battalion, which had been promised it would never have to fight, was starting to dwindle even before a shot was fired. A third of them deserted on the way, or soon after their first taste of combat.

A far more reliable unit was the SS Unteroffizier Schule commanded by Obersturmbannführer Hans Lippert. While Lippert waited at Grebbeberg for his own men to arrive, he was given a naval contingent – Schiffs-Stamm-Abteilung 10 – whose commander warned him that his men had no infantry training, and a so-called Fliegerhorst-Bataillon of Luftwaffe ground crew, whose military experience had been ‘limited to rolling fuel drums’. Lippert’s growing but very mixed force was designated the ‘Westgruppe’, supposedly the counterpart to the far more powerful ‘Ostgruppe’ based on the Hohenstaufen Division. Bittrich rashly predicted that ‘with a counter-attack from both east and west, the enemy forces would be destroyed on 19 September.’

Aware that only a small proportion of the airborne division had reached the bridge, Bittrich ordered Harzer’s Hohenstaufen to concentrate all available forces on building two blocking lines to ensure that no more British troops got through. Möller’s pioneer battalion of the Hohenstaufen had already taken up position on the eastern edge of Oosterbeek along the railway line which ran south to Nijmegen. His was the force which had repulsed Dobie’s 1st Battalion in the night. ‘Around us frightened people in houses looked at us with hostile expressions,’ he wrote. ‘We dug in amid this jungle of gardens and villas like imitation chateaux, of hedges and fences and outhouses.’ They were soon reinforced with the divisional flak detachment. Beyond them Möller had positioned another company, commanded by Obersturmbannführer Voss, in and around a large house on the corner of the Utrechtseweg partly concealed by thick rhododendron bushes.

So while Harzer’s Hohenstaufen faced west to block the rest of the 1st Airborne, the bulk of Harmel’s Frundsberg Division was ordered to destroy resistance at the bridge as soon as possible so that reinforcements could be sent south to ensure the defence of Nijmegen. The only alternative route was round to the east and then to ferry troops and vehicles across the Neder Rijn at Pannerden, two kilometres north of the River Waal.

The 1st Battalion of the 21st SS Panzergrenadier-Regiment was ordered to secure key buildings just to the north of the bridge. One company had a single half-track, which panzergrenadiers usually called a ‘rolling coffin’. A British 6-pounder armour-piercing round went through one side and out the other, leaving little damage except for two round holes. Amazed at their luck, they pulled back rapidly. ‘We all acted like heroes for each other’s benefit,’ a panzergrenadier called Horst Weber admitted, ‘when actually inside we were quivering with fear.’

Their company was ordered to occupy the imposing courthouse – the Paleis van Justitie. Convinced that British paratroopers had occupied it, they wheeled up their anti-tank gun and simply blasted a side wall at point-blank range until they had a breach large enough to enter. A soldier from the panzer regiment in the company, who was known simply as ‘Panzermann’ because he still wore his black uniform, was the first through the hole. It was a large building with marble columns in the hall and many cellars, but no British. They set up their machine guns to cover the Walburgstraat and the market place.

Another member of his battalion ‘saw some Dutch civilians during the fighting. They came out on the street to bandage the wounded. We used to try and avoid shooting them, although this was not always possible.’

At the northern end of the road bridge, Frost’s force stood-to before dawn on that Monday morning. With spare magazines to hand and grenades ready primed, they waited to see what daylight would bring. ‘A cold mist rising off the Rhine almost obscured the bridge,’ wrote a member of the mortar platoon. His lieutenant decided to set up his observation post on the top of the warehouse facing the bridge where the battalion’s Vickers machine guns were installed. ‘Their ugly snouts were a little back from the windows in the shadows, but they still had a very fine field of fire.’ While awaiting the inevitable German counter-attack, the machine-gun crews busied themselves on needless little tasks in the tense atmosphere. But when the mortar platoon commander checked the line they had just laid down to the field telephone in one of the mortar pits, he found that the handset they had brought with them did not work. He flung it against the wall with fearful swearing. They had to try another method, with a paratrooper taking down the range he estimated from the map, and then shouting it down from the back of the building to the mortar pits dug in on the grass islands either side of the main road.

Several German trucks, whose drivers seemed unaware of recent developments around the bridge, were shot to pieces with rapid fire from Bren guns, rifles and Stens. The soldiers on board who were not killed were taken prisoner. Several of them came from a V-2 rocket group, but naturally did not admit that to their captors. The PIAT teams and the crews of 6-pounder anti-tank guns held back. They knew better than to waste ammunition on soft-skinned vehicles. The American OSS officer Lieutenant Harvey Todd with the Jedburgh team was installed in the attic of brigade headquarters, as he recounted in his after-battle report. ‘I had a good o[bservation] p[ost] and sniper position in the rafters of a building near a small window in the roof overlooking the road and the bridge. I killed three Germans here as they tried to cross the road.’ ‘One badly wounded German’, noted a mortarman, ‘pulled himself with his hands to within a couple of yards of safety and then was despatched by one of our own snipers who had been following his progress with detached interest.’

At 09.00, just out of sight on the southern part of the bridge a column of some twenty vehicles was forming up from Sturmbannführer Gräbner’s reconnaissance battalion of the Hohenstaufen. Gräbner had briefly halted on the bridge just out of view. Round his neck, he wore the Ritterkreuz, which he had received the day before. Gräbner was known to despise half-measures. Evidently convinced that a sudden attack at full speed would do the trick, he raised his arm. All the drivers began revving their engines. Gräbner gave the signal, and all the vehicles accelerated forward. Puma armoured cars, the latest version of the eight-wheeler, led the way followed by open half-tracks, and finally Opel Blitz trucks with only sandbags as protection for the soldiers on board.

A signaller up in an attic shouted ‘Armoured cars coming across the bridge!’ Frost experienced an irrational surge of hope that this might be the vanguard of XXX Corps arriving ahead of time, but he was swiftly disabused. He and his men watched in fascination as the column had to slow down to weave its way through the burned-out trucks on the northern ramp. The paratroopers expected the leading vehicles to blow up on the necklace of anti-tank mines they had laid across the bridge, but the first four Pumas, firing their 50mm guns and machine guns, accelerated away past them into the town.

Determined to make up for their slow start, Frost’s paratroopers finally reacted with every rifle, Bren and Sten gun available. The mortar platoon and the Vickers machine guns also opened up with devastating effect. The anti-tank gunners from the Light Regiment found their range, and the next seven vehicles were hit and set ablaze. Gräbner’s men, having never experienced a battle in such a confined space, tried to escape, but vehicles crashed into each other. A half-track backed into the one behind and they became locked. The open half-tracks proved to be death-traps. Their ambushers were able to fire down and lob grenades into both the driver and panzergrenadier compartments. One tried to escape down the side bank of the ramp and smashed into the school building. Another crashed through a barrier and fell to the riverside road which ran under the bridge.

Some of those trapped on the bridge jumped from the parapet into the Neder Rijn. Gräbner himself is said to have been killed when he climbed out of his captured Humber armoured car to try to sort out the chaos. The smell of roasted flesh permeated the air for hours afterwards, mixed with the stench of the oily-black smoke from the blazing vehicles. Gräbner’s body was never identified among all the other carbonized corpses.

Lieutenant Todd up in the roof shouted down targets to the 6-pounder anti-tank crew below. ‘Several German infantrymen tried to cross the bridge, but from my OP I couldn’t miss,’ he reported. ‘Killed six as they tried to cross the roadblock along the bannister of the bridge. Then someone spotted me. A sniper’s bullet came thru the window and glanced off my helmet, but glass and splinters from the window were in my eyes and face.’ Todd was taken down to the aid station in the cellar. The paratrooper who took over his position in the roof was wearing his maroon beret instead of a helmet. A German sniper saw it and killed him.

Mackay’s sappers in the school building had no anti-tank weapons, so they could do no more than fire their personal weapons and throw grenades down into the backs of half-tracks. At one point mortar shells began to fall on the school, but Mackay quickly realized that they were being fired at by one of their own teams. ‘Cease fire, you stupid bastards!’ he yelled. ‘We’re over here.’ Major Lewis in the same building recorded that they could hear a badly wounded German soldier, who must have crawled from one of the burning half-tracks, calling for his mother. They could not see him, but the calls went on for most of the day and half the night until he fell silent. It was ‘a ghostly feeling’, Lewis recalled.

Once the furious firing had died down, a defiant ‘Whoa Mahomet!’ rang out. This was the 1st Parachute Brigade’s war cry from North Africa. ‘Soon it was reverberating all around that bridge,’ Mackay recorded. It would follow almost every engagement from then on because it was also a good way of establishing which buildings the defenders still held. When the cheering ended, all that could be heard was a siren howling away. ‘Will we be getting overtime for this, Sir?’ called a platoon joker. ‘The whistle’s just gone.’

After only a short pause, the Germans launched another attack from the opposite direction, with infantry, several half-tracks and intense mortar fire. The PIAT teams and anti-tank gun crews accounted for another four armoured vehicles, but the desperate calls for stretcher-bearers indicated a heavy toll of British casualties too. When there were not enough stretchers, the wounded were carried on doors ripped from their hinges to the cellar under brigade headquarters. It began to fill rapidly. The two doctors, Captains Logan and Wright, and their orderlies were overwhelmed with work, but there was no hope of evacuating any wounded to 16 (Para) Field Ambulance in the St Elisabeth Hospital. The dead were stacked in a yard behind brigade headquarters.

Colonel Frost wondered how on earth they were going to feed their increasing bag of prisoners. One of them held in the cellars of the government building was identified as a Hauptsturmführer in the 9th Panzer-Division Hohenstaufen. Frost went down to ask him what SS panzer divisions were doing in Arnhem. ‘I thought you were supposed to be finished after the Falaise Gap,’ Frost said. The SS officer replied that they might have received a good beating there, but they had been refitting round Apeldoorn. ‘We are the first instalment,’ he told Frost confidently, ‘and you can expect more.’

Although firing died away from time to time, any movement between houses could be dangerous, with German riflemen constantly waiting for targets. British paratroopers noted that German marksmanship was very bad in the initial engagements, perhaps because they were so tense.

The mortar platoon commander at the top of the building with the Vickers machine guns was able to work out the ranges easily from a map. He soon had his 3-inch mortars below in the weapon pits dropping their bombs on the German vehicles gathered at the south end of the bridge. Through his binoculars, he could watch several direct hits with fierce satisfaction at such a successful ‘stonk’. But by the afternoon Knaust’s Kampfgruppe, including the panzer company from Bielefeld, had assembled just to the east of the bridge ramp in a dairy on the Westervoortsedijk. Using that street and the one parallel running along the line, they attacked houses held by Digby Tatham-Warter’s A Company. Although they seized two buildings and penetrated under the bridge, Knaust was clearly shaken on losing three out of his four company commanders in the savage battle.

What with the fighting at the bridge, several British groups besieged close to the centre and a major battle developing west of the St Elisabeth Hospital, the city of Arnhem had become even more of a battleground than many of its inhabitants realized. Those in the northern part of Arnhem had no idea of what was happening in the centre and towards the bridge. They assumed that the fighting that they could hear was south of the Neder Rijn. Those who went off to try to buy bread returned rapidly ‘looking as white as death because of the shooting in the streets’. Many buildings including the two barracks, the Willemskazerne and the Saksen-Weimar-kazerne, as well as the big Wehrmacht depot, were still on fire.

Much of the town centre was also blazing. What sounded like heavy rain ‘turned out to be the crackle of flames’, one man wrote. The Germans, convinced that enemy spotters or snipers were in the huge tower of St Eusebius, known as the Grote Kerk, kept shooting at it. The company of the 21st Panzergrenadiers even began firing at the tower with their 75mm anti-tank gun. ‘The noise it made in these narrow streets was deafening. The reverberations seemed to go on endlessly.’ Several people saw ‘the hands of the large clock on the church spin round crazily – as if time were racing by’.

From Den Brink round to the grim façade of the St Elisabeth Hospital and beyond, the Germans had the advantage of the high ground. The 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions struggled in vain to depose them. To make matters worse, as they tried to attack north around the Y junction they were exposed to the fire of German flak batteries positioned on the south bank of the Neder Rijn. And ahead of them, a German Mark IV panzer, an assault gun or an armoured car would emerge to shell them, then pull back quickly as soon as they saw a 6-pounder anti-tank gun deployed.

A platoon commander in the 1st Battalion was at first encouraged by their progress. ‘Advancing on high ground,’ he jotted in his diary. ‘Ordered to capture the hill in front with houses and a wool factory with high chimneys. Got to houses. Had a good shoot from a house still occupied by screaming Dutch. What a row! Little girl about ten years of age from another house hit, shot in thigh. My medics attended to her, but we had to hold the mother off as she went berserk. Huns running.’ But then the attack flagged and the reinforced Germans came back. ‘Hit by a sniper and then by a machine-gun.’ Platoon commanders were suffering a terrible attrition rate. ‘Under fire from across the river,’ wrote another. ‘Cut off. German grenade in the arm and in the eye. It was just like being stabbed with a red-hot needle. I was very frightened because I thought I was blind.’

There were many grisly sights. ‘Smoke and fire darkened the streets. Broken glass and broken vehicles, and debris littered the road.’ A paratrooper with the 1st Battalion described ‘the smouldering body of a lieutenant’ ahead of them. A tracer bullet had ignited the phosphorus bomb in one of his pouches and he had burned to death. A distraught father was seen pushing a handcart with the body of a child. ‘‘A dead civilian in blue overalls lay in the gutter, the water [from a burst main] lapping gently around his body.’ There were also bizarre moments in the middle of this battle. A Dutchman stepped out of his house and asked two British soldiers in English if they would like a cup of tea. A little further back along the route they had come, the bodies of British paratroopers lay ‘everywhere, many of them behind trees or poles’, Albert Horstman of the Arnhem underground recorded. He then saw ‘a man, about middle-aged, who wore a hat. This man went to every dead soldier, lifted his hat, and stood in silence for a few seconds. There was something terribly Chaplinesque about the scene,’ Horstman concluded.

The confused fighting meant that there were many stragglers from both the 1st and 3rd Para Battalions. Regimental Sergeant Major John C. Lord, an imposing moustachioed Grenadier recruited by Boy Browning (and known as ‘Lord Jesus Christ’ by the paratroopers), was trying to get a grip on the situation round the St Elisabeth Hospital when struck by a German bullet. ‘It felt exactly like I had been hit in the arm by a hammer,’ he recorded. The impact spun him round and he landed flat on his back. ‘My arm was paralysed and bleeding badly, but strangely enough it did not hurt.’ Lord was carried into the hospital, where he soon acquired a deep admiration for the professionalism and good humour of the nurses. None of them had opted to leave even while the battle raged round the hospital, and the building was hit by heavy flak shells from across the river.

One of the German nuns was spoon-feeding a ninety-year-old man when his head was literally severed by a shell, which must have passed within millimetres of the nun. Frozen in horrified disbelief, ‘she sat there staring with the plate still in her hand.’ Because of the heavy firing, Dutch doctors began transferring their civilian patients to the Diaconessenhuis, a clinic outside the battleground. To identify themselves they wore sheets and helmets painted white with a red cross. Sister van Dijk thought they looked like crusaders.

Soon after midday, a still optimistic Bittrich estimated that Frost’s force at the bridge was only ‘around 120 strong’. The British may have suffered a lot of casualties that morning, but the Frundsberg was not going to destroy them as quickly as he had hoped.

At the road bridge, Tony Hibbert, the brigade major, suggested that in Lathbury’s absence Lieutenant Colonel Frost should become acting brigade commander, while his second-in-command should take over the battalion. They hoped that this would be a very temporary measure. One of Frost’s radio operators picked up the net of XXX Corps. The signal sounded so strong that they assumed they could not be very far off. Frost and his officers imagined that the arrival of the Guards Armoured Division was only a matter of hours away.