15

Arnhem Tuesday 19 September

After the confused fighting on the Monday, with the 3rd and 1st Battalions trying to break through to the bridge, their last hope was another push that evening. In the end it did not take place until the early hours of Tuesday. At a candle-lit council of war in a ruined house, Lieutenant Colonel Dobie of the 1st Parachute Battalion took the lead in the absence of any formation commander. They were close to the Rhine Pavilion, a waterside building below the St Elisabeth Hospital. A mistaken report that the Germans had recaptured the north end of the bridge prompted divisional headquarters to tell them to cancel the attack, but then it was on again.

Dobie was joined by Lieutenant Colonel Derek McCardie of the South Staffords and Lieutenant Colonel George Lea of the 11th Parachute Battalion. There was no contact with Fitch of the 3rd Parachute Battalion, even though he could not have been far away. Dobie was still utterly determined to support Frost at the bridge, despite the fact they would again suffer from machine-gun fire from the left, assault guns ahead and flak guns firing across the river into their right flank. The idea was to attack in the dark and fight through to the bridge before first light.

The Germans had pulled back their blocking line. This allowed the British to reoccupy the St Elisabeth Hospital and Major General Urquhart to escape from his attic hideout. But Standartenführer Harzer’s decision to withdraw to a new line on the far side of some open ground, some 500 metres east of the Rhine Pavilion and 200 metres beyond Arnhem’s Municipal Museum, was to create a better killing field.

Soon after 03.00, Dobie’s battalion advanced rapidly along the riverfront, only to encounter Fitch’s 3rd Battalion withdrawing, after their own bruising battle to get through. Fitch had little more than fifty men standing out of the whole battalion. Dobie refused to believe they could not break through, and marched on. Fitch turned his exhausted men around, and agreed to support Dobie’s attack. On the Utrechtseweg up the hill, the South Staffords, followed by the 11th Parachute Battalion, skirted the Museum and then ran into the assault guns of Harzer’s blocking line. They too suffered fusillades and machine-gun bursts from the embankment beyond the railway line to their left, and heavier-calibre flak firing from across the river, where the Germans had occupied a brickworks. The 88mm shells exploded with devastating effect, while the rounds from the dual 20mm flak guns blasted off limbs with such force that the shock alone could kill.

A Parachute Regiment lieutenant identifiable only as ‘David’ wrote down some impressions while in hiding after the battle. ‘I was obsessed by recurring scenes of the nightmare passed – of Mervyn with his arm hanging off, of Pete lying in his grotesque attitude, quite unrecognizable, of Angus lying in the dark clinging to the grass in his agony, of the private shouting vainly for a medical orderly – there were none left – of the man running gaily across an opening, the quick crack and his surprised look as he clutched the back of his neck, of his jumps so convulsive as more bullets hit him. How stupid all this war game is, I only hope the sacrifice that was ours in those days will have achieved something – yet even at this moment I feel that it hasn’t. It will remain a gesture.’

Möller’s 9th SS Pioneers, well concealed back on the eastern edge of Oosterbeek, ambushed British troops coming on behind. ‘The pioneers fired,’ he recounted. ‘Panzerfausts literally blew groups of paratroopers apart, and flamethrowers sprayed fire at the enemy . . . The Utrechtseweg was a channel of death.’

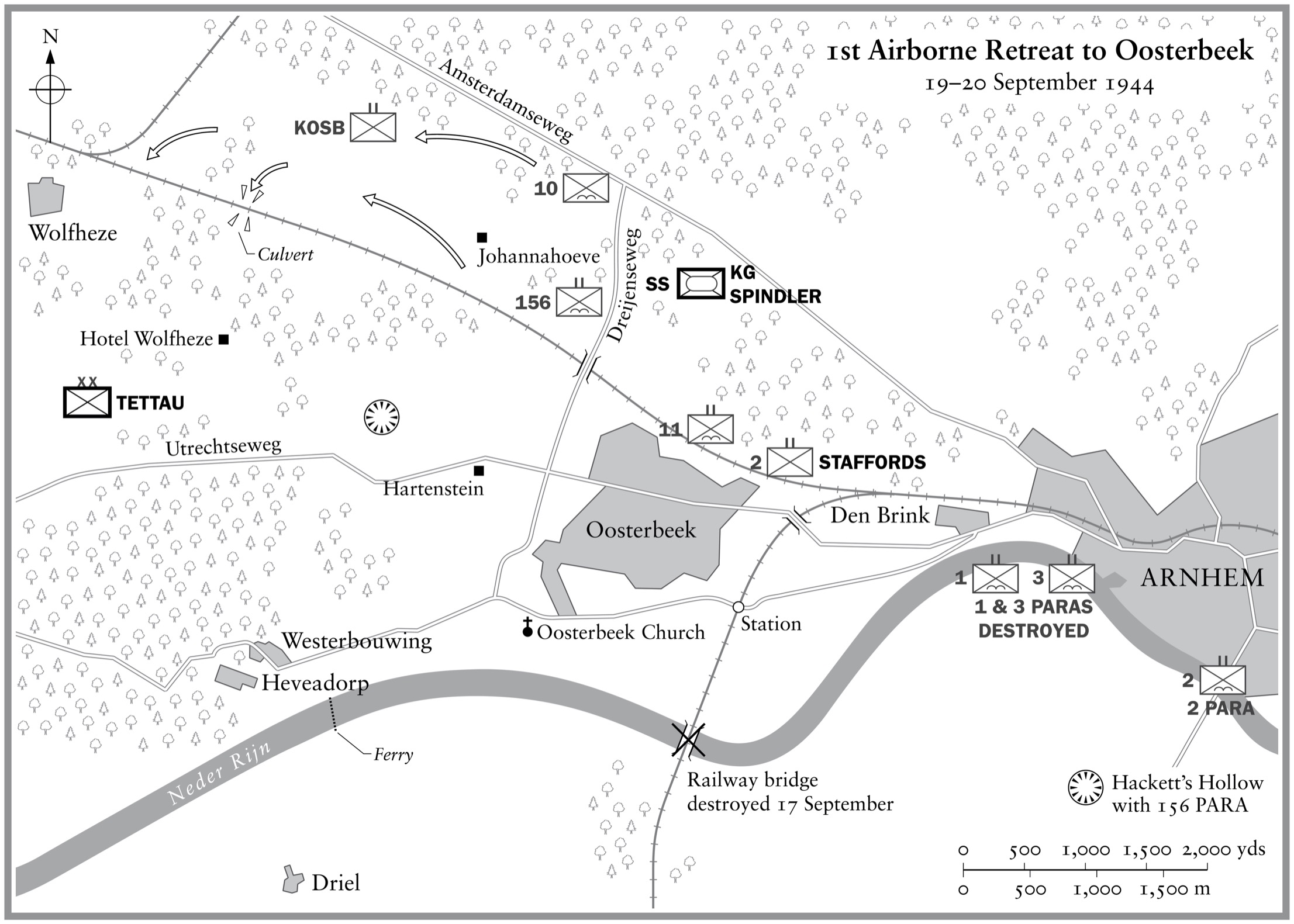

The rest of Kampfgruppe Spindler to the north, between the railway line and the Amsterdamseweg, was fighting the 10th and the 156th Parachute Battalions. They were also harassing the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, preparing to defend Landing Zone L, north of the Bilderberg woods, where the third lift was due later in the day. And with General von Tettau’s forces pushing in from the west, the 1st Airborne Division was nearly surrounded.

Further to the east on the Utrechtseweg near the hospital, Major Robert Cain with the 2nd South Staffords saw a man beckon him over. He then handed Cain a rifle and pack. He was caring for a wounded British soldier inside and did not want to suffer the consequences of having a weapon in the house. ‘Germans,’ he said apologetically, and to emphasize the point, he put two fingers to his temple to represent a pistol. Soon afterwards, Cain and his company took up another position to fight back against a German sally from the centre of Arnhem. Cain grabbed the Bren gun and fired off a whole magazine. Realizing that he was standing on a pile of flat stones, he looked down and saw that they were gravestones with Hebrew inscriptions. They were standing in a Jewish graveyard which had been presumably been smashed by the Germans or Dutch Nazis.

With German reinforcements arriving with heavy weapons, the British did not stand a chance against intense fire from three sides. After the near-destruction of Fitch’s 3rd Battalion, Dobie’s 1st Battalion was broken in semi-suicidal attacks against German positions. Hardly a man was left unwounded. The only escape was to seek shelter in nearby houses, but the panzergrenadiers, supported by assault guns, had them trapped, and took most of them prisoner little more than an hour later.

A couple of hundred metres to the north, the South Staffords were running low on anti-tank PIAT rounds. The Museum, which the British called the Monastery, had been their aid post. It now had to be evacuated, but the doctor there, ‘Basher’ Brownscombe, remained with those who could not be moved. He was murdered several days later in hospital by a Danish member of the SS, who was later tried and hanged for the crime. A defensive position in the dell behind the Museum was also abandoned due to concentrated mortar fire.

Major Blackwood, arriving with the 11th Battalion, saw signs of the previous day’s fighting: ‘Wires and cables down, an occasional barricade of burned out vehicles, some dead Germans cluttering the streets. We moved under fire to a position on the hill near the big hospital and dug in there while a battalion put in an attack on the lower level. The noise was terrific. Somewhere behind the hospital was a large calibre gun popping off, but an attempt to find out more about it only brought a shower of Spandau bullets about my ears. So for the most part we lay on the qui vive looking at the horribly stiff bodies of an officer and men of the 1st Brigade which blocked the gateway on our flank.’

At around 09.00, German Mark IV tanks appeared, as well as assault guns. They were held off at first by the last few PIATs, as a member of the South Staffords recorded, ‘but at about 11.00 all PIAT ammunition was exhausted and tanks over-ran the position, inflicting heavy casualties and splitting the Battalion into pockets.’ They had no anti-tank guns forward because the convex curve of the hill shielded enemy armoured vehicles until they were almost on top of them. As the Staffords pulled back near the St Elisabeth Hospital, the same private saw a British soldier jump from a first-floor window of a house on to the back of a tank in an attempt to drop a grenade into the turret, but he was shot down before he had a chance.

Behind the South Staffords, the 11th Parachute Battalion tried to advance on the railway line and embankment up to the left, but the attack never got off the ground. Between the Utrechtseweg and the river, survivors from the 1st and 3rd Parachute Battalions pulled back to the Rhine Pavilion. Colonel Fitch was not among them. He had been killed by a mortar bomb. With hardly any medics or stretcher-bearers left, the wounded were told to try to make their way as best they could to the St Elisabeth Hospital, even though it was now back under German control.

At 10.30, Colonel Warrack, the deputy head of medical services, managed to contact the 16th (Parachute) Field Ambulance in the St Elisabeth Hospital. He was using the telephone of a civilian in Oosterbeek, whose son was in the Dutch SS. Warrack heard that, although the Germans had taken away the head of 16 Field Ambulance and many of the orderlies, two surgical teams were still operating. They had nearly a hundred casualties, many of them serious cases. Warrack could hear the sound of battle in the background, with machine guns and an assault gun firing constantly, as he conversed with the field ambulance’s dental officer. Later in the morning Brigadier Lathbury was brought into the St Elisabeth Hospital from his hiding place, with the bad wound in his thigh. He had removed all badges of rank and pretended to be Corporal Lathbury.

Bizarrely in the circumstances of such a British disaster, a German SS panzergrenadier with only a flesh wound was crying in the hospital. One of the remaining British doctors told him to shut up because he was not dying. A Dutch nurse explained that the man was crying not from pain, but because the Führer had decreed that the Allies must never cross the Rhine, and they had done so.

Even the 11th Parachute Battalion behind the South Staffords found itself forced to retreat, as Major Blackwood recounted: ‘13.00 hrs, message to say that our attack on the Arnhem bridge had been beaten back and that German tanks had outflanked and surrounded us . . . B Company took up positions in houses overlooking a main crossroads. Our orders were brief – wait for the tanks, give them everything we had in the way of grenades, shoot up as many infantry as we could before we died. With Scott I entered one of the corner houses, said “Good morning” to the worried looking tenant, and went upstairs to the room with the most commanding view. It was a remarkably fine room to die in. A plaster cast of a Madonna in the corner, two crucifixes, three ornately framed texts, and a picture of the Pope. We removed all glass and china to a remote corner, laid out our grenades, ammunition and weapons on the bed, and had a drink of water. Scott, who is an RC, made furtive use of some of the religious adornments and I put in a wee word or two of my own.’

Just outside the hospital, Major Cain was taking shelter in a long air-raid trench on the east side of the St Elisabeth Hospital. He told his men to stay down as they could hear a German assault gun approaching. It was little more than fifty metres away. Peering over the rim of the trench, Cain could see the commander standing, with head and shoulders exposed. He wore black gloves and held some binoculars. Cain, who had nothing more than his service revolver, was horrified to hear a burst of fire from along the trench. One of his men had tried and failed to kill the commander, who dropped inside and closed the hatch with a clang, and then the assault gun turned towards them. Three of Cain’s men panicked. They scrambled from the trench and were cut down by machine-gun fire. Cain pulled himself out of the trench as the assault gun manoeuvred, and then rolled down the reverse slope behind, which led to a steep drop into the courtyard of the hospital. Just beyond the hospital, he came across men from the 11th Battalion. He wanted to get his revenge on the assault gun, but they had no PIAT ammunition left.

Instead, Cain was told to round up as many men as he could and seize the high ground at Den Brink. The plan was for Cain’s force on Den Brink to act as a pivot, for the 11th Parachute Battalion to attack another hill to the north of the railway line called Heijenoord-Diependal. Cain and his men passed the round panopticon prison with its shallow dome and then rushed Den Brink from the side. To Cain’s relief, there was little resistance when they put in their attack and took the feature, but a tangle of tree roots made digging trenches difficult. He urged his men to hurry. He knew how fast the Germans would range in with their mortars, and they did, with tree bursts. In a short time, two-thirds of his force had suffered shrapnel wounds. Soon after 14.00, Cain felt there was no alternative but to pull back. Not only was the attempt to get through to Frost’s force at the bridge defeated, but four battalions had been savaged in the attempt. With most officers killed or wounded, a chaotic retreat was under way. Men appeared out of the smoke of battle, running back in ones and twos ‘like animals escaping from a forest fire’.

Once released from hiding early in the morning, General Urquhart and his two companions found a Jeep and drove to the Hartenstein. ‘As I came down the steps,’ wrote the padre of the Glider Pilot Regiment, ‘who should be ascending but the General. Several saw him but nobody said a word. We were completely taken aback. His return was the signal for a great resurgence of confidence.’

Confidence was needed badly, as Urquhart’s chief of staff Charles Mackenzie had just found. On a check of the divisional area, he was disturbed to find a machine-gun nest and a Bren-gun carrier abandoned. He then came across a group of about twenty soldiers in a panic, with some of them shouting ‘The Germans are coming! The Germans are coming!’ He and Loder-Symonds calmed them down and Mackenzie drove the carrier back to the Hartenstein. He found Urquhart, standing on the steps, about to explode, no doubt because on his return he had found that nothing was going to plan. ‘We assumed, sir, that you were gone for good,’ Charles Mackenzie said to him.

Around the Hartenstein, armed members of the LKP underground group were forcing the NSB collaborators they had rounded up to dig trenches. Other Dutch volunteers were collecting corpses to move them to burial places. The glider pilot padre, meanwhile, set off in a Jeep with two young SS trooper prisoners, still in their tiger camouflage smocks, sitting on the front. They were going to bury General Kussin and his companions.

Early that morning staff officers at the Hartenstein suddenly discovered that ‘a BBC set, brought in to send news releases back to London, had communication with its base set so we received permission to send our messages over it. Arrangements were made by BBC in London to get personnel from SHAEF to receive the messages and relay them to British Airborne headquarters at Moor Park.’ For the next two days, ‘this was the only reliable radio contact we had in the Division to the outside world.’

Just north of Oosterbeek, while the other four battalions tried and failed to get through to the bridge, Hackett’s 4th Parachute Brigade had been fighting its own battle. During the night the 156th Parachute Battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Sir Richard Des Voeux, had continued its advance between the railway line and the Amsterdamseweg towards Arnhem. Hackett’s plan was to seize the high ground at Koepel beyond a north–south road through the woods called the Dreijenseweg, which ran down to Oosterbeek, but this was the blocking line of the Kampfgruppe Spindler. It was a strongly held position with steeply rising wooded ground on the eastern side of the road where Spindler’s force of panzergrenadiers and gunners was dug in, supported by eight-wheeler armoured cars, half-tracks and assault guns. At around midnight, the 156th Battalion had run into outposts west of the road. Colonel Des Voeux decided to back off and wait until first light to get a better idea of what they were up against.

Expecting a dawn attack, the Germans pulled in their outposts. First one company of the 156th attacked and, as soon as it had crossed the road, suffered devastating losses from the concentration of German firepower. It was virtually wiped out. Another company was sent in supposedly to turn the German flank, but it was a continuous line. They too could not spot the well-camouflaged trenches and gun pits in the woods.

Major John Waddy sighted a German half-track with 20mm double flak guns, and began to stalk it. High in one of the trees, however, was a sniper who shot him in the groin before he could fire the PIAT. One of Waddy’s sergeants, a huge Rhodesian, picked him up in his arms like a child, saying to him, ‘Come on, Sir. This is no place for us,’ and carried him back to the battalion aid post. Waddy’s travails were not over. As a patient in the Hotel Tafelberg he was wounded twice more, first by German mortar fire and, towards the end of the battle, by shell fragments from British artillery firing from south of the river.

In the course of the morning, the 156th Battalion lost almost half its strength. Brigadier Hackett had to pull it back. To the north, the 10th Parachute Battalion commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Ken Smyth advanced past the discouraging sight of casualties brought back on a procession of Jeeps. Smyth’s lead company encountered a similar volume of fire to the 156th and went to ground. Reluctant to destroy another company, Smyth asked Hackett’s permission to try to outflank the end of the blocking line by sending a company round north of the Amsterdamseweg. Soon the 10th Battalion was pinned down by the much stronger and better-munitioned Kampfgruppe Spindler.

Hackett’s brigade needed to hold that line, even if no further advance was possible, because less than a kilometre to the west of the Dreijenseweg lay Landing Zone L where part of the third lift was due to arrive that afternoon. Already the King’s Own Scottish Borderers were having a hard time trying to defend its perimeter. Meanwhile, General von Tettau’s forces were advancing on Wolfheze to their rear, while the very high railway embankment along their southern flank risked trapping them in a desperately vulnerable position. Both Urquhart and Hackett now suddenly recognized the danger the 4th Parachute Brigade was in.

When the order to fall back reached the 156th Battalion, Major Geoffrey Powell was furious. They were given just fifteen minutes’ warning, and to withdraw quite openly in daylight invited disaster. ‘It was ludicrous, insane. We were ordered to just break off and fall back. The move was chaotic.’ Under constant attack by the Germans, the battalion was split and then fragmented.

Captain Lionel Queripel had taken over command of the 10th Battalion company north of the Amsterdamseweg. With his slightly whimsical expression, Queripel did not seem to be a man likely to win the Victoria Cross for a whole series of actions. His men referred to him as Captain Q, and thought he looked more like ‘a country parson than a soldier’. Yet bravery can never be judged by appearances. Although himself wounded in the face, he first carried a crippled sergeant out of danger. He then stormed a German position, which had two machine guns and a captured British 6-pounder anti-tank gun, killing the crews. He was hit again. Then, as Germans threw stick grenades, he picked them up and threw them back. ‘Finally, as the German counter-attack increased greatly in strength, he ordered his men to pull back while he held off the Germans with hand grenades and a Sten gun.’ Queripel’s self-sacrifice could end only in death.

Sergeant Fitzpatrick, the man he had carried out of danger, was tended to by their medical officer, Captain G. F. Drayson, kneeling beside him. A mortar bomb came down. It exploded and almost decapitated the doctor who fell across Fitzpatrick’s body, pinning the weakened man to the ground. Sergeant Fitzpatrick began to sob, appalled that Drayson should have died trying to help him.

The broken battalion reached the landing zone as the gliders carrying the Polish anti-tank squadron began to approach. Back at the Hotel Hartenstein, the American fighter control team led by Lieutenant Davis were trying to contact Allied fighters to protect the incoming lift. Davis managed no more than one brief exchange with a Spitfire pilot, who then could not hear anything because of the flak explosions all around him. ‘All through the operation the Luftwaffe was active, but it was a very peculiar activity,’ Davis reported after the battle. ‘The FW 190s and Me 109s were over every day except two, and their tactics were always the same. They would sweep back and forth about 4,000 feet, drop to 2,000 and then peel off as if to strafe us. But I doubt whether they fired over 500 rounds in all the passes they made at us. It looked as if they were afraid to use their ammunition and then be unarmed in case our fighters would come, and were merely trying to bolster German morale.’

On the ground, the withdrawal of the 10th and 156th Battalions enabled the Germans to start attacking the landing zone from the woods. The King’s Own Scottish Borderers found themselves under heavy fire. ‘See my first live Jerry and put a bullet through him,’ one of them recorded. ‘He went down on his knees, so I rolled out of Tony Morgan’s way, and he put a burst into him. More Jerries coming out of the woods under cover of M.G.34 and Schmeisser fire, which we return. I got another cert.’

At about four the cry went up ‘Third lift here!’, the chaplain of the Glider Pilot Regiment recorded. ‘All we could do was gaze in stupefaction at our friends going to inevitable death. We watched in agony the terrible drama. It was heroic in the extreme. We saw more than one machine blazing yet continuing on its course. It now became borne in on us that we faced terrible opposition.’

While the departure of the Polish Parachute Brigade had been cancelled from airfields in the Midlands because of bad visibility, the second glider group bringing the rest of the anti-tank squadron managed to lift off in thirty-five gliders from the airfields of Salisbury Plain well to the south. But only twenty-six arrived together with British gliders on Landing Zone L. ‘The landing took place in the midst of the fiercest battle and sustained enormous losses,’ a Polish account stated. ‘Gliders were literally shot to pieces in the air, during landing and on the ground.’ Many were injured on landing. ‘The British could not help as they had their own problems.’

The Germans were even firing with Nebelwerfer multi-barrelled mortars on to the landing ground. The confusion was such that Polish soldiers opened fire on 10th Battalion paratroopers retreating across the landing zone, thinking they were Germans. They killed several of them including Lieutenant Paddy Radcliffe, the commander of the machine-gun platoon. ‘Absolute hell,’ wrote Major Francis Lindley of the 10th Battalion. ‘Germans had the open ground surrounded with flak guns and machine-gun. Gliders landing all round us. C-47 flew over with flames shooting out of it. Stirling crashed near the road. Poles just started firing at everything.’ Finally the Poles realized from the yellow triangles being waved at them that they were firing at the British. Lieutenant Colonel Smyth of the 10th Battalion apparently had ‘tears in his eyes’ when looking at the sad remnants of his command.

‘Later in the afternoon the resupply ships, Stirlings and Dakotas, came over and ran into terrific ack-ack barrages,’ one report stated. ‘Too many of them get hit and go down flaming and too much of the supply drop goes to the Germans . . . It had been expected that we would control the area where the supplies were dropped. Evidently no message had got through changing the DZ. We tried while the planes were overhead to contact them with VHF on the three frequencies but got no reply. Yellow ground panels and smoke pots were set out but only a few of the planes were able to see them because of the tall trees and the low altitude of the planes.’

Another posthumous Victoria Cross was awarded for bravery that afternoon. Flight Lieutenant David Lord had brought his C-47 Dakota down below cloud cover just north of Nijmegen. A German flak battery opened fire and set his starboard engine ablaze. Lord asked how much longer to the drop zone. ‘Three minutes’ flying time,’ came the reply. The plane began to list as the fire spread. Over the intercom Lord told his crew: ‘They need the stuff. We’ll go in and bale out afterwards. Get your chutes on.’ He told his navigator to go back and help the four Royal Army Service Corps soldiers who would be pushing out the baskets. The mechanism was broken, so they had to manhandle each container of ammunition out of the door. They managed only six out of eight, so Lord insisted on going round again to drop the last two. As soon as they were gone, Lord shouted ‘Bale out! Bale out!’ Lord kept the aircraft steady long enough for them to jump, but it was not long enough for him and he was killed.

Flying Officer Henry King, his navigator, had no idea after parachuting whether Lord had died or had managed to crash-land the plane. ‘Lord was a strange fellow,’ he observed later. ‘He had studied for the ministry, but left a seminary to join the RAF in 1936. He was rather a grimly determined chap.’ King encountered some members of the 10th Battalion. They offered him a cup of tea and some chocolate. ‘That’s all we’ve got,’ one of them said.

‘What do you mean, that’s all you’ve got?’ King replied. ‘We just dropped supplies to you.’

‘Sure you dropped our tins of sardines, but the Huns got them. We got nothing.’

Many if not most of the containers drifted towards German positions, to the frustration of the paratroopers. ‘Now we too smoked English cigarettes and ate English chocolate,’ SS-Hauptsturmführer Möller exulted.

Möller’s divisional commander, Standartenführer Harzer of the Hohenstaufen, described how Model visited his command post daily. He arrived with a small escort, and demanded a short, sharp situation report as soon as he stepped in the door. Whenever there was a problem, the commander on the spot had to offer three different solutions. Once that was over, Harzer was allowed to request more men, vehicles, weapons, ammunition and supplies. Model would then make his decision, and telephone his chief of staff General Krebs, ‘and a few hours later, transport columns and troops were re-directed towards Arnhem’. Since the Hohenstaufen lacked transport, the Wehrmacht trucks would deliver the shells straight to the gun lines. When flamethrowers were requested for street-fighting, Model had them flown to the division from an ordnance department in central Germany. The German army was based on a ruthless prioritization which the British army manifestly failed to match.

Once Model had finished with Harzer, he then went forward to visit the command post of each Kampfgruppe, where he would question officers and soldiers alike on the progress of the attack and on morale. As Möller indicated, morale was high not just because of their certainty of winning this battle after the defeat in Normandy, but because of the cornucopia of Allied parachute containers raining down on them. Having captured the orders which revealed the signals and identification panels for guiding the Allied supply drops, further generous supplies could be expected. The panels were quickly manufactured and distributed the next day.

In addition, the British in their retreat were losing control of their drop zones and lacked radio contact to warn the RAF. Allied aircraft would soon be at even greater risk. Harzer’s strength was about to be increased by the arrival of a flak brigade commanded by Oberstleutnant Hubert von Swoboda of the Luftwaffe, an Austrian. This consisted of five flak battalions from the Ruhr, with a mixture of 20mm, 47mm, 88mm and even 105mm anti-aircraft guns. Most of the guns had to be towed by farm tractors or even wood-burning trucks, but the II SS Panzer Corps was still able to assemble nearly 200 anti-aircraft guns west of Arnhem, positioned to support the ground troops as well as engage Allied aircraft. And yet, according to Major Knaust, Bittrich was still anxious about the outcome of the battle. When he visited Knaust at his command post just east of the ramp that day, he said: ‘Knaust, can we hold out here another 24 hours? We’ve got to gain time to allow the divisions from Germany to arrive.’ Both Knaust’s and Heinrich Brinkmann’s Kampfgruppen had suffered heavy casualties in the house-to-house fighting north of the bridge. Knaust’s well-worn tanks either broke down or were knocked out rapidly by the British 6-pounder anti-tank guns. ‘It would seem a miracle how they manhandled heavy guns up on to the upper floors,’ Harzer commented later. ‘The heavy infantry weapons fire from basements or withdrawn from windows so they cannot be spotted.’

In Arnhem during the previous night, the Germans had forcibly evacuated any remaining Dutch civilians from houses near the northern end of the road bridge. One of the last sounds that Coenraad Hulleman remembered before leaving his home was the unearthly racket of an upright piano upstairs being riddled with bullets.

As expected, the German attack came at dawn. The defenders at the bridge had already heard all the firing to the west where the other battalions around St Elisabeth Hospital were trying to fight through to them. Harmel’s Frundsberg seemed to be concentrating its efforts on finishing off the school on the east side of the ramp, using Knaust’s Kampfgruppe and his few remaining panzers. ‘On Tuesday morning’, Lieutenant Donald Hindley recalled, ‘the tanks came back and they started shelling this house very heavily.’ Three of the airborne sappers managed to stalk one of the tanks and knock it out. ‘The crew got out and crept along the wall of the house till they came to rest beneath the window where I was sitting. I dropped a grenade on them and that was that. I held it for two seconds before I let it drop.’

Sapper John Bretherton was shot through the forehead. ‘Bretherton, for a split-second, looked surprised. Then he dropped to the ground without a cry.’ Another sapper suddenly gripped Sergeant Norman Swift’s arm and asked him if he was all right. Swift could not understand since he felt fine. He followed the soldier’s gaze and saw a large pool of what looked like blood by his feet, and then realized it was rusty water which had seeped from one of the bullet-ridden radiators. Another sapper, who was badly shell-shocked, walked out of the building. He was calling out, ‘We’re all going to die.’ Everyone yelled at him to come back, ‘but he was too far gone to understand and walked straight into the line of German fire.’

In a house opposite the school the panzergrenadier Rottenführer Alfred Ringsdorf was exasperated by the way the school’s defenders ‘were shooting through the windows in the stairwell so that we could not use the stairs’. The only way of dealing with its defenders, he argued, was to fire a Panzerfaust to explode just below the windowsill. That would kill any rifleman waiting to pop up for another shot. Along with the rest of Obersturmführer Vogel’s company, he had no cigarettes, and they were desperate to capture some prisoners in order to take theirs.

Captain Mackay had issued the stimulant Benzedrine to his men, which caused double vision in some and occasionally provoked hallucinations, of which the most common was that XXX Corps had arrived on the other side of the bridge. Some men became obsessed with this vision. Others, without the influence of Benzedrine, were eagerly awaiting the drop of the Polish Parachute Brigade on the polderland near the southern end of the bridge. Frost, knowing that the Poles would face a desperate battle there, had assembled a ‘suicide squad’ led by Freddie Gough to fight across the bridge to join them. He was not to know that Sosabowski himself was fuming, because he had been told at the last moment that only his anti-tank squadron was going in on that day.

With German snipers focusing on the windows of the school, the sappers and paratroopers from the 3rd Battalion had to be silent as well as invisible. ‘We bound up our feet with strips of rags,’ Mackay wrote, ‘to make our movements through the house silent. The stone floors were covered with glass, plaster and were slippery with blood, especially the stairs.’ German marksmanship had improved. ‘We were now getting a considerable number of sniper bullets entering our houses,’ another paratrooper wrote in a diary, ‘and needless to say suffering considerable casualties, although it seemed to us that we had inflicted at least double the amount on the enemy. We were still unable to contact the Divisional Commander, although the wireless team had received the Second Army quite clearly, but unfortunately they were not receiving us.’

The American OSS lieutenant Harvey Todd recorded with satisfaction three more kills during the Germans’ dawn attack. He left his perch in the roof of brigade headquarters a little later. Around midday the enemy launched another counter-attack, a much more serious one. Todd recorded five more kills from his position in the roof, but then had to get out rapidly when a German machine-gunner zeroed in on him. A Bren-gunner in the building was killed so Todd took over his weapon. He spotted a 20mm flak gun being used against another house, and managed to shoot the crew.

‘Great joy all round’ broke out when a Focke-Wulf 190 roared in from the south over the bridge to drop a bomb, which proved a dud as it bounced up the main concourse of the Eusebiusbinnensingel towards the town centre. Sappers in the school fired Bren guns at the plane. The pilot banked to escape their bursts, but his port wing caught the church steeple to the west and the plane crashed with a massive explosion. This produced another roar of ‘Whoa Mahomet!’ from all the buildings around the bridge.

The defiance belied the fact that Frost’s force was suffering badly. ‘We now had over 50 casualties in our building alone,’ Lieutenant Todd reported. The battalion doctor Captain Jimmy Logan and his orderlies won universal praise for accomplishing what they did without running water, and when they were almost out of clean bandages, morphine and the other medical necessities of war. Patients had to use empty wine bottles and fruit jars to urinate in. The Rev. Father Bernard Egan had worked well with Logan ever since the battalion’s battles in North Africa. Logan knew by then which of his patients were Catholic, and he would warn Father Egan as soon as one of them needed the last rites. One man just before dying of his wounds said, ‘And to think I was worried that my chute wouldn’t open.’

Captain Jacobus Groenewoud, the Dutch leader of the Jedburgh team, tried to ring the St Elisabeth Hospital but the line was dead. Groenewoud and Todd decided to run to a doctor’s house near by to ring the hospital from there. When about halfway, and just as they were steeling themselves for the next dash across a street, Captain Groenewoud was killed by a sniper. ‘The bullet went in his forehead and out the back of his head,’ Todd wrote. Todd ducked into a doorway, and found a man who spoke a little English. They managed to sneak to the next-door house where there was a telephone which worked. He called the hospital, but the doctor he spoke to explained it would be impossible to send an ambulance. They had tried already, but the Germans warned that any ambulance sent out would be fired on. The doctor also explained that as the Germans controlled the hospital approaches, where a considerable battle was going on, they wanted the British wounded moved so there was more space for their own casualties. When Todd managed to return to brigade headquarters, the news was equally bad there. In one of the few radio transmissions to work, they had learned that XXX Corps had still not captured the bridge at Nijmegen, but were about to make an attempt that evening.

Later that morning, the Germans bombarded the school with Panzerfausts. Thinking that they had silenced the defenders, they surrounded the school. Mackay told his men to prepare two grenades each, and on his command they dropped them from the upper windows. They grabbed their weapons and finished off any who had not been blasted by the grenades. ‘It was all over in a matter of minutes leaving a carpet of field-grey around the house.’ Mackay was recognized by his men as being one of those rare beings who were virtually fearless.

Another was Major Digby Tatham-Warter. He inspired everyone, almost playing the fool, by walking up and down in the open twirling an umbrella he had found in one of the houses, and putting on a bowler hat like Charlie Chaplin. When Freddie Gough pointed this out to Colonel Frost, he simply said, ‘Oh yes, Digby’s quite a leader.’ Lieutenant Patrick Barnett, who commanded the brigade defence platoon, saw Tatham-Warter walking along the street in a heavy mortar barrage with his umbrella up. Barnett stared at him in astonishment and asked him where he was going. ‘I thought I’d go and see some of the chaps over there.’ Barnett laughed and pointed at the umbrella as German mortars kept firing. ‘That won’t do you much good.’ Tatham-Warter looked at him, eyes wide open in mock surprise. ‘Oh? My goodness, but what if it rains?’

Some soldiers became fired up with bloodlust. Private Watson was sent to replace a Scot, predictably known as ‘Jock’. ‘He told me to get the bloody hell out. He said he had ten notches on his [rifle] butt already and he planned to get ten more of the bastards before they got him. He looked like the kind of crazy bastard who’d do it.’ Watson went back a couple of hours later. ‘Jock was sprawled on the floor. He’d taken a bullet right through the mouth.’ Freddie Gough remembered that one of their best snipers was Corporal Bolton, one of the few black soldiers in the division. Bolton, a ‘tall, languid’ man, took great satisfaction in his work, ‘crawling all over the place, sniping’, and would ‘grin widely’ after each victory.

Brigadeführer Harmel ordered his men to cease fire while he sent a captured British soldier to Colonel Frost, to suggest they meet to discuss surrender. The panzergrenadiers seized the opportunity to eat or sleep. ‘After a pause’, wrote Horst Weber, ‘the English paratroopers suddenly let out a terrific yell: “Whoa Mahomet!” We all sprang up, wondering what was happening. We were frightened at first by this terrible yell . . . Then the shooting began again.’

Frost was determined to fight on, yet because they were so short of ammunition he felt compelled to issue an order to shoot only when repelling German attacks. During the next onslaught a voice was heard to shout at the enemy, ‘Stand still you sods, these bullets cost money!’

Now pushed back well to the west of the bridge, the remnants of the four battalions which had tried to break through were in full retreat, harried by their German pursuers. ‘At every house we passed was a man or a woman with a pail of water and several cups. We needed those drinks,’ wrote Major Blackwood in the 11th Parachute Battalion. ‘The people flocked round us, smiling, laughing, offering us fruit and drink. But when we told them the Boche was coming, their laughter turned to tears. As we dug our slit-trenches in the gardens, the melancholy procession of blanket carrying refugees began to move past.’

Blackwood’s men cannot have occupied those trenches for long, because the retreat gathered pace and became even more chaotic. Most platoons and companies had lost their officers in the fighting. ‘A sergeant whose boots were squelching blood from his wounds’, recorded a soldier from the South Staffords, ‘gave us the order to try to get out of it, and make our way back to the first organised unit we came to . . . Everyone still alive seemed to be wounded somewhere or deeply shocked.’

The other retreat westwards, that of the 4th Parachute Brigade, was to escape being caught against the steep railway embankment. There were only two ways to get through, the level crossing at Wolfheze and a culvert under the railway through which a Jeep could just be driven, providing the windscreen was folded flat and the driver lay almost sideways. The 6- and 17-pounder anti-tank guns were too large. Using all their remaining strength, some anti-tank crews tried to manhandle their guns up the vertiginous slope of the embankment. The Germans, seizing the opportunity, sent machine-gun groups up on to the embankment to fire along the railway tracks.

When self-propelled assault guns appeared, even the bravest paratroopers were shaken, knowing how ill-armed they were. A chief clerk of the 4th Parachute Brigade recounted how a major shouted, ‘You white-livered bastards. Come and get them!’ He did not last long, brought down by German fire as he charged forwards. A pathfinder sergeant near Wolfheze saw ‘hundreds of airborne running in panic. They were pouring back, some of them without arms . . . We went along the railway line and I remember seeing a Pole up on top of the embankment trying to fire a six-pounder anti-tank gun. He was shouting in Polish. We saw that the breech block of the gun had been removed. We tried to make him understand the gun wouldn’t fire, but it was no use. We left him. He was out of his mind and I felt terribly sorry for him.’

The King’s Own Scottish Borderers also took part in the disastrous withdrawal from the landing zone and the adjoining farm of Johanna Hoeve. Colonel Payton-Reid, its commanding officer, described how his battalion, ‘which at four o’clock in the afternoon was a full-strength unit, with its weapons, transport and organisation complete, whose high morale had been further boosted by a successful action against attacking enemy, and which was prepared to meet anything coming [at] it, was reduced within the hour to a third of its strength, with much of its transport and many of its heavy weapons lost, one company completely missing and two more reduced to half-strength’. Payton-Reid led the remainder all the way round and back to north Oosterbeek to a small hotel called the Dreijeroord, which the regiment would always know as ‘the White House’. Payton-Reid knocked on its door at 21.00, to be greeted as a liberator, but he felt a hypocrite. He knew he was ‘bringing them only danger and destruction. By the next night the building was reduced to a shell.’

Caring for the wounded in such a retreat became doubly difficult. With the advance of General von Tettau’s forces from the west, Colonel Warrack had to organize the rapid evacuation of patients from the dressing station at Wolfheze. Most were moved to the Hotel Schoonoord. Warrack visited it at 11.00 and found that ‘casualties were coming in fast’. In fact the total had passed 300, and they had taken over nearby buildings to house the overflow. Hendrika van der Vlist, the daughter of the owner, had put on her girl-guide uniform because it was made of tough material. Along with other young women volunteers, they started by washing the faces of the wounded and their hands to reduce the danger of infection.

They also had to act as interpreters. Both British and German wounded were brought in, and at first it was too complicated to keep them apart. Even though the Germans were prisoners, their attitude had not changed. One of them summoned her: ‘Nurse, cold towel! I have a headache.’ She observed that ‘The Herrenvolk has become so used to commanding that they do not know how to behave differently.’ On the other hand, a German who had never wanted to be in the army soon made friends with the British soldiers either side of him. They started teaching each other words and phrases in their own language.

She then found a Dutch boy in German uniform who had been shot through the jaw. He was a traitor, but she could not help feeling pity. Later in the week, she discovered that he was ‘mentally defective’. She was surprised to find how quickly she adapted to dealing with horrible wounds. ‘A week ago I would have been frightened at the sight of such a horribly injured face. Now I am used to it. It is nothing but wounds that I see here. And the heavy sickly smell of blood hanging all over the place.’

Urquhart went to the Schoonoord to visit the wounded that afternoon. Soon afterwards the rest of the 131st (Parachute) Field Ambulance arrived from Wolfheze, having just got out in time as Helle’s SS Wachbataillon approached. To help feed such a crowd, farmers brought in livestock killed in the fighting and locals arrived with produce from their gardens and orchards, especially tomatoes, apples and pears. The wounded were not very hungry but they badly needed water, the hospital’s greatest problem. The bathtubs in the hotel had fortunately all been filled on Sunday as a precaution just after the airborne landings. Volunteers now started to drain the central heating system and radiators to replace what was being used from the baths.

Other civilians turned up at the Schoonoord, particularly divers who had emerged from hiding, including former political prisoners and several Jews. They had come because they thought they must be safe there. The general impression that the Allies had as good as won the war was already proving very dangerous for many in occupied Europe.

With German losses mounting at the bridge that day, Brigadeführer Harmel welcomed the arrival of the 280th Assault Gun Brigade from Denmark, which had been diverted to Arnhem instead of Aachen. One of their men later recounted that they lost 80 per cent of their vehicles in the fighting in and around Arnhem, which he described as far more savage than anything he had witnessed in Russia. British paratroopers would hold their fire and let the assault guns pass, then shoot them from behind because the armour was so much thinner there. The close-quarter fighting wrecked the nerves of the crews, he added. They were terrified of being burned alive by phosphorus grenades.

Above all Harmel eagerly awaited the arrival of Kompanie Hummel from the 506th Heavy Panzer Battalion, with its Tiger tanks. They had been unloaded early that morning in Bocholt, close to the Dutch border, after their Blitztransport across Germany. But only two of the Tiger tanks survived the eighty-kilometre road-march. The rest were rendered useless along the way, mostly from broken tracks and sprockets. The two serviceable tanks went into action that evening, guarded by panzergrenadiers from the SS Frundsberg. Their armour-piercing rounds went right through a house, leaving a hole each side. ‘They looked incredibly menacing and sinister in the half-light,’ Colonel Frost recounted, ‘like some prehistoric monster as their great guns swung from side to side breathing flame.’ When the ammunition was switched to high explosive, their 88mm guns began to smash the houses around the heads of the defenders. At times it was hard to breathe, so thick was the dust of pulverized masonry. The building which housed battalion headquarters was hit, and Digby Tatham-Warter and Father Egan were both wounded.

In the school, Major Lewis ordered his men into the cellars, since the Tigers could not depress their guns far enough to shoot so low. Once they withdrew, the defenders reoccupied the first floor. A brave anti-tank gunner took on one of the Tigers single-handed. He ran out, loaded his gun and fired, then ran back behind the house. Fortunately he was under cover when the tank destroyed the gun, yet one of the two Tigers was knocked out that very evening. A round from a different 6-pounder hit the turret, badly wounding the commander and another member of the crew, while a second round jammed the main armament. The second Tiger then developed mechanical problems and also had to be withdrawn for major repairs at Doetinchem. ‘Thus ended the first day’s engagement in a fiasco,’ wrote a member of the Kompanie Hummel.

Harmel ordered heavy howitzers and more assault guns to be brought in to take over the task of blasting British strongpoints at close range. To the British defenders, this suggested that the Germans were not in a hurry, which meant that XXX Corps had still not crossed the bridge at Nijmegen. In fact Harmel was under great pressure. Generalfeldmarschall Model wanted the 1st Airborne destroyed and the Arnhem bridge opened quickly so that they could speed reinforcements to Nijmegen, having heard that XXX Corps had reached the edge of the city. That evening Model put the so-called Division von Tettau, which had just occupied Wolfheze, under the command of II SS Panzer Corps ‘for the complete destruction of the enemy west of Arnhem’. The Germans could not help exaggerating their already considerable successes that day. Bittrich claimed 1,700 prisoners taken, four British tanks and three armoured cars knocked out. It seems that Bren-gun carriers now counted as tanks.

The bombardment of the houses round the bridge was far worse than what the 2nd Battalion had endured in Sicily. ‘It seemed impossible for the mortaring to get any heavier but it did,’ wrote Private James Sims, ‘bomb after bomb rained down, the separate explosions now merging into one continuous rolling detonation, the ground shook and quivered as the detonations overlapped.’ He was curled up at the bottom of a trench out on the Eusebiusbinnensingel. ‘Alone there in that trench it was like laying in a freshly dug grave waiting to be buried alive.’ It was not just the shrapnel which killed. In brigade headquarters, Lieutenant Buchanan, the intelligence officer, dropped dead from bomb blast without a scratch on him.

At one stage in the fighting that day, Lieutenant Barnett of the defence platoon saw two German medics dash out to tend to British wounded in the street, until they were shot by a German MG-34 and fell across the bodies of those they were trying to help. ‘They had been shot down by their own people.’ The artillery forward observation officer was badly wounded, so Lieutenant Todd took over, having served in the cannon company of his American division. To speed things up, Harmel sent in the newly arrived pioneers with flamethrowers to set fire to the houses. ‘As night came, rows and rows of houses stood in flames,’ Harmel recorded. ‘But still the British did not give up.’ As a house was set on fire, they ‘mouseholed’ through from one to another. There was no water to extinguish the blaze.

Some of the fires had been started to make sure that the streets were constantly lit, as one panzergrenadier explained. ‘Then if they tried to run across they made good targets.’ But now Harmel’s own panzergrenadiers were also suffering from the fires. ‘The houses were burning and it was terribly hot,’ Alfred Ringsdorf recorded. ‘I got cinders in my eyes more than once and the smoke made them smart. It also made you cough. Ashes and soot from the rubble made things even worse. It was hell.’ He had still not entirely recovered from a close shave earlier in the day. ‘I took a prisoner, quite a heavy, strong man. I had him stand up and raise his hands so that I could search him. I bent down in my search and at that very moment he uttered an “Oh,” and crumpled up dead. It was an English bullet meant for me which had killed him. For a second I was paralysed. Then, I broke out in a cold sweat and, driven by habit, dived for cover.’

Ringsdorf hated close combat, because ‘it was one man against another, face to face, and also you never knew when the enemy would pop up.’ He avoided the danger of moving around at night and stumbling into the enemy. The one thing he longed to do was to take off his helmet because it was so heavy and his neck was so stiff. ‘The English were very good sharpshooters. Most of the German soldiers, dead and wounded, were hit in the head.’ He thought that the only reason he survived the battle was because he was leading. ‘The enemy rarely shoots at the first man, but wait to see if there are more soldiers coming. They let the first couple of men go by, then attack those coming up next.’

As well as the fires deliberately started, much of the city centre was ablaze, including the towers of the two churches, the St Eusebius and the St Walburgis. Their bells made strange noises when struck by bullets. Because of the conflagration, the prison director in Arnhem opened the cells of all but the most dangerous prisoners. The liberated inmates emerged with white faces and heads shaved, in their prison clothes. The blaze continued to spread. ‘You can read the newspaper by the light of the fires,’ an anonymous diarist wrote laconically. Civilians started to flee the burning city whenever there was a lull in the shelling. The old and the ill had to be transported on handcarts or even in wheelbarrows.

The British at the bridge had no illusions about the danger. The crackle of burning buildings and the occasional crump as floors and façades collapsed gave an apocalyptic impression. Frost and Gough climbed to the attic to watch. If the wind changed direction then they would be trapped in a conflagration which might turn into a firestorm.