18

Arnhem Bridge and Oosterbeek Wednesday 20 September

Wednesday dawned with light rain, which did little to dampen the flames around the north end of Arnhem bridge and the town centre. One of the few civilians left in the area gazed in horror at the church of St Walburgis and noted that ‘the towers looked like great columns of fire’.

Frost’s force suspected that they did not have what Monty considered a ‘sporting chance’ of holding the bridge, yet they also guessed that their presence had more than inconvenienced the Germans. Brigadeführer Harmel, while directing operations in Nijmegen from the north bank of the Waal, longed to hear that the British 1st Airborne had been crushed. ‘Damn them, but they’re stubborn!’ he cursed. He desperately needed the road bridge opened because the improvised ferry system at Pannerden simply could not cope with reinforcements and supply. Bittrich’s headquarters felt obliged to explain to higher command that the delay in eliminating Frost’s battalion was due to their ‘fanatical doggedness’. Frost and his men would never have accepted the word ‘fanatical’, but they would have acknowledged a thoroughly British bloody-mindedness.

Ammunition was almost totally exhausted. Not a single PIAT round remained to deal with armoured vehicles. Although Frost was no longer optimistic about their chances, a belief had taken hold that ‘this is our bridge and you’ll not set one foot on it.’ A signaller told him that they had made contact with divisional headquarters. Frost had his first chance to talk to Urquhart, who told him that things were very difficult for them too. Frost assured him that they would hold on as long as possible but ammunition was the problem, along with medical supplies and water. He then asked about XXX Corps. Urquhart knew little more than he did, and Frost sensed that he and his men would not be relieved. Jokes about the Guards Armoured Division stopping to blanco their belts and polish their boots were no longer funny. The day before he had discussed with Freddie Gough of the reconnaissance squadron what they should do if they had to break out. The obvious direction was due west to Oosterbeek, but Frost thought it might be better to slip out in groups towards the north through the back gardens.

The desire to know the whereabouts of XXX Corps continued to preoccupy everyone. Captain Bill Marquand in brigade headquarters sent a signalman up into the attic with a 38 Set. Desperate to make contact, he was broadcasting in clear, over and over again: ‘This is the 1st Para Brigade calling Second Army.’ There was still no response.

More and more buildings had been destroyed by fire or shelling. Often the two were linked as the Germans used phosphorus shells to accelerate the process. After capturing the second last house on the eastern side, the Germans sent in pioneers to fix charges to the underside of the bridge so that it could be blown if British tanks did break through from Nijmegen. A counter-attack led by Lieutenant Jack Grayburn forced them back, and sappers removed the charges. The Germans attacked again and Grayburn, wounded twice already, was killed with a burst of machine-gun fire from a tank. He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

Accompanied by panzergrenadiers in their camouflage smocks, a battalion of Royal Tiger tanks reached Arnhem that morning, making a terrible noise as it crossed the Willemsplein from the direction of Velp. ‘However, a sixty-ton panzer colossus’, Generaloberst Student acknowledged, ‘could not be very effective in the narrow streets and the house-to-house fighting.’ They at least did not run the risk of crushing gun crews. Artillery pieces fired on a smooth asphalt surface meant that the gun could run back up to ten metres each shot, and it was not easy to jump clear in time. Kampfgruppe Brinkmann, meanwhile, ‘passed from a period of exceptionally savage night fighting’, Brigadeführer Harmel wrote, ‘to a technique of smoking out individual pockets of resistance with Panzerfausts and flamethrowers’. With the British blinded by smoke, Brinkmann’s force advanced. ‘A great many prisoners, mostly wounded, were taken.’

In the school, Captain Eric Mackay issued two pills of Benzedrine to each of his sappers but took none himself. ‘The men were exhausted and filthy,’ Mackay recorded. ‘I was sick to my stomach every time I looked at them. Haggard and filthy with bloodshot red-rimmed eyes. Almost everyone had had some sort of dirty field dressing and blood was everywhere.’ Their faces, with three days’ growth of beard, were blackened from fighting fires. Parachute smocks and battledress trousers had been cut away by medics to tend their wounds. Everyone suffered from a terrible thirst. They had been drinking the rusty water from those radiators which had not been hit.

The Van Limburg Stirum School now looked like a sieve. ‘Wherever you looked you could see daylight.’ It was the last British redoubt holding out on the east side of the bridge, which is why the Germans again concentrated such firepower upon it. Mackay was concerned that it might collapse on top of them, as Harmel had hoped, with his tactic of blasting the building systematically from the top. Shells from one of the newly arrived Mark VI Tigers set fire to it once more early in the afternoon.

Mackay recognized that they urgently needed to do something for the thirty-five wounded men in the cellars. Major Lewis had himself just been hit in an explosion. There were only fourteen able-bodied men left, so if the fires in the building intensified, or if the floors began to collapse, they would not have time to get them out. They decided to break out so that the school could be surrendered and the remaining wounded in the cellars left to be cared for by the Germans. With six men acting as vanguard with their remaining Bren guns, and eight acting as stretcher-bearers for four of the wounded, they made their move. But the break for freedom was short-lived. Almost all were captured.

Ringsdorf from the Kampfgruppe Brinkmann recorded seeing someone look out from a cellar aperture. ‘My immediate reaction was to toss a hand grenade through the cellar window. Then I heard a voice shouting “No! No!”, and the sound of moans. I had already pulled the pin on my grenade so I tossed it in the direction of another building. Then, I went down into this cellar alert for any trap, and entered saying “Hands up!” The cellar was full of wounded English soldiers. They were very frightened, so I said “It’s OK, it’s good.” I took them prisoner and had them taken back to be tended . . . These wounded men were quite helpless and many had to be carried away. They looked terrible.’ Ringsdorf showed impressive restraint, because his company commander Obersturmführer Vogel, whom he had greatly liked, had just been cut almost in half by British machine-gun fire.

Frost was discussing the situation with Major Douglas Crawley, one of his company commanders, when they were both badly wounded by a mortar bomb. Captain Jimmy Logan, the medical officer, suggested morphine, but Frost refused, as he needed to keep his wits about him. He fought the pain and nausea for as long as possible, and could not even face drinking whisky. He told Major Freddie Gough to take over command but to check all important decisions with him first. Eventually he accepted morphine and was carried down to the cellar of brigade headquarters on a stretcher.

Although Frost still wanted to hold on to their positions, they had lost the houses closest to the bridge. The Germans were soon on the ramp. Using tanks, they shunted the burned-out carcasses of Gräbner’s reconnaissance vehicles to one side. So just before Tucker’s paratroopers and the Grenadiers secured the road bridge at Nijmegen, the Frundsberg was already sending through those first reinforcements of panzergrenadiers and Tiger tanks.

When Frost awoke that evening it was dark. He heard ‘some shell shock cases gibbering’. Many more started shaking uncontrollably every time there was an explosion. Apparently there was one soldier whose black hair went white in the course of less than a week from stress. The doctor, Captain Logan, warned that the building was on fire, so Frost sent for Gough and told him to take over command in full. First they would move those fit to fight and the walking wounded – only around a hundred remained – then Gough was to arrange a truce to hand the wounded over to the Germans. One paratrooper wrote, ‘It was undoubtedly the right decision, but some men who were in a bad state felt aggrieved at being abandoned, even though the battalion doctor and medical orderlies were staying with them.’

As soon as the truce began the Germans tightened the ring. They then insisted that they must take the British Jeeps to evacuate the wounded. By that stage Gough was in no position to refuse such a condition. When the truce to remove the wounded began in earnest, Lieutenant Colonel Frost removed his badges of rank. Captain Logan went out with a Red Cross flag. There was a shot, and he yelled back ‘Cease fire!’ ‘Only wounded in here,’ he added. The shooting died away. Outside, he explained to a German officer that they needed to get everyone out before the building burned down or collapsed. The officer agreed and gave his orders. As German soldiers came down the stairs, ‘a badly wounded paratrooper brought out a Sten gun from under his equipment, complete with full magazine, with every intention of giving the Germans a fitting reception, but luckily he was overpowered and the gun taken from him.’

A German officer entered the cellar in greatcoat and steel helmet, carrying an MP-40 sub-machine gun. He looked around at the dreadful sight, and told the men following to help the wounded out. Both Germans and British carried them out before they could be burned to death. Frost was taken out on a stretcher and laid on the embankment next to the bridge. He found himself next to Crawley, with whom he had been wounded. ‘Well,’ he remarked, ‘it looks as though we haven’t got away with it this time.’

‘No,’ Crawley replied, ‘but we’ve given them a damn good run for their money.’ But Frost felt anguished at leaving his battalion in such a state. ‘I had been with the 2nd Battalion for three years. I had commanded it in every battle it had fought and I felt a grievous loss at leaving it now.’

Lance Bombardier John Crook, when told to surrender, found it harshly ironic to be surrounded by the German prisoners he had been guarding. He smashed his rifle, ‘a forlorn action in the circumstances’. A ‘big SS panzergrenadier’ pointed a sub-machine gun at him, shouting ‘Hände hoch!’ Then some of their German prisoners tried to console him and his comrades by patting them on the back, saying ‘Kamerad.’ There were altogether some 150 German prisoners, many of them wounded.

In the courtyard wounded British paratroopers were greeted by the sight of a 6-pounder anti-tank gun on its side, with the rubber tyres still burning and the crew dead around it. Some of their guards, from the army and not the Waffen-SS, allowed them some food and something to drink, before moving them on. The paratroopers were both shaken and secretly gratified to see the numbers of German dead lying around. But the sight hardened the mood of some SS panzergrenadiers.

After a thorough search for hidden weapons, half a dozen paratroopers and sappers were forced to stand against a wall. The SS panzergrenadiers formed a semi-circle facing them and they were joined by a very young soldier with a flamethrower in the middle. One of them gave the order to prepare to fire. ‘Say your prayers boys,’ a paratrooper said out loud, and another began to recite ‘The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.’ Suddenly an SS officer ran up shouting, ‘Das ist verboten. Nein! Nein! Nein!’ The panzergrenadiers lowered their weapons with obvious reluctance.

A member of the underground who had been fighting with the paratroopers was identified by the Germans, because both his hands were bandaged from terrible burns. He had tried to pick up a phosphorus bomb to throw it away. ‘He was forced to his knees and shot through the back of the head by a German officer.’

As the truce came to an end, Major Digby Tatham-Warter took charge of some of the survivors, who had left the buildings where wounded were being evacuated. They took up new positions in a garden area behind brigade headquarters and the ruins of a few houses, but their perimeter was now tiny and almost every building was on fire. Others tried to escape during the night through the German cordon, hoping to get through to the 1st Division at Oosterbeek. Very few made it.

Most of the wounded were taken off in the captured Jeeps to a church where a British doctor treated their wounds. The more serious cases were taken directly to the St Elisabeth Hospital. The surgeon Dr Pieter de Graaf, who had ordered the wounded to be moved back from the windows because of all the shooting in the area, was struck by how little shouting there was in the British army. When a group of SS came in to round up malingerers among the German patients, the SS doctor started shouting orders in all directions. ‘Nobody really cared,’ de Graaf noted. ‘The man yelled because there was nothing he could do but make a noise. The British and Dutch doctors just went about their business, pretending he wasn’t there.’ There had been only one civilian casualty in the last two days. An elderly patient had stuck his head out of an upstairs window to see what was going on, and was shot by a sniper. He was buried in the hospital grounds along with the bodies of British soldiers.

Although the fighting around the hospital was over, the Germans were still nervous. A tank rumbled down the road towards the St Elisabeth Hospital, its tracks making a metallic screeching sound. The turret traversed round to the right, with the gun pointing at the main entrance of the hospital. The hatch opened and a German officer in black panzer uniform appeared. He shouted that he wanted to see the director, claiming that he had been shot at from the hospital building, and unless he appeared immediately he would open fire with his tank. The German surgeon came out instead. Originally captured by the British, he had in theory assumed control when the Germans retook the hospital, but he continued to work with Dutch and British doctors as before. He told the panzer officer that he had been very well treated and he was sure nobody had fired from the hospital. The tank commander calmed down and carried on along the road towards Oosterbeek, where the next battle was about to take place.

On the previous afternoon, stragglers from those other battalions which had tried to reach the bridge had started to appear in Oosterbeek. They had presented a sorry sight. A heavy officer and NCO casualty rate over the last two days meant that most men were leaderless. The disaster they had experienced attempting to fight into Arnhem had risked undermining good order and military discipline. A company sergeant major in the 11th Battalion recounted that during the retreat a staff sergeant, whom he had charged with an offence in the past, drew his revolver to scare him, saying, ‘Now we are all equal. Nobody will know.’ And yet reassuringly the sergeant major had also overheard a private say to his companion, clearly another Londoner and fellow fancier, ‘I’ll be glad to get back to my pigeons.’

The commanding officer of the Light Regiment, Lieutenant Colonel ‘Sheriff’ Thompson, was alarmed to find that there was no covering force in front of his pack howitzers just below Oosterbeek church. ‘Some troops of 11 Para Battalion [were] very shaky,’ he noted. Thompson began to organize the remnants of the four battalions into a defence line facing east to protect his guns. Having lost at least three-quarters of their strength, the 1st, 3rd and 11th Parachute Battalions as well as the South Staffords were now reduced to less than 450 men combined. They became known for the time being as Thompson Force. Under the command of the redoubtable Major Robert Cain, the South Staffords based themselves near Oosterbeek church in the laundry. The old rectory of the ter Horst family, already the aid station for the Light Regiment, would also become an improvised hospital for the south-eastern sector of the perimeter.

Private William O’Brien in the 11th Parachute Battalion limped into the church, and lay down on one of the pews for a sleep. The church had been badly battered and he could see the sky overhead through the shell-damage to the roof. ‘I began to think of my own skin now,’ O’Brien admitted. ‘It seemed to me they had got us into something they had no business getting us in.’ But according to his account an unnamed Dutch lady (who was probably Kate ter Horst) came to encourage the wounded, saying, ‘Have courage, God is with you.’ A number were not convinced that He was, but they were impressed by her bravery during bombardments, and the occasional malingerer was shamed into returning to his post.

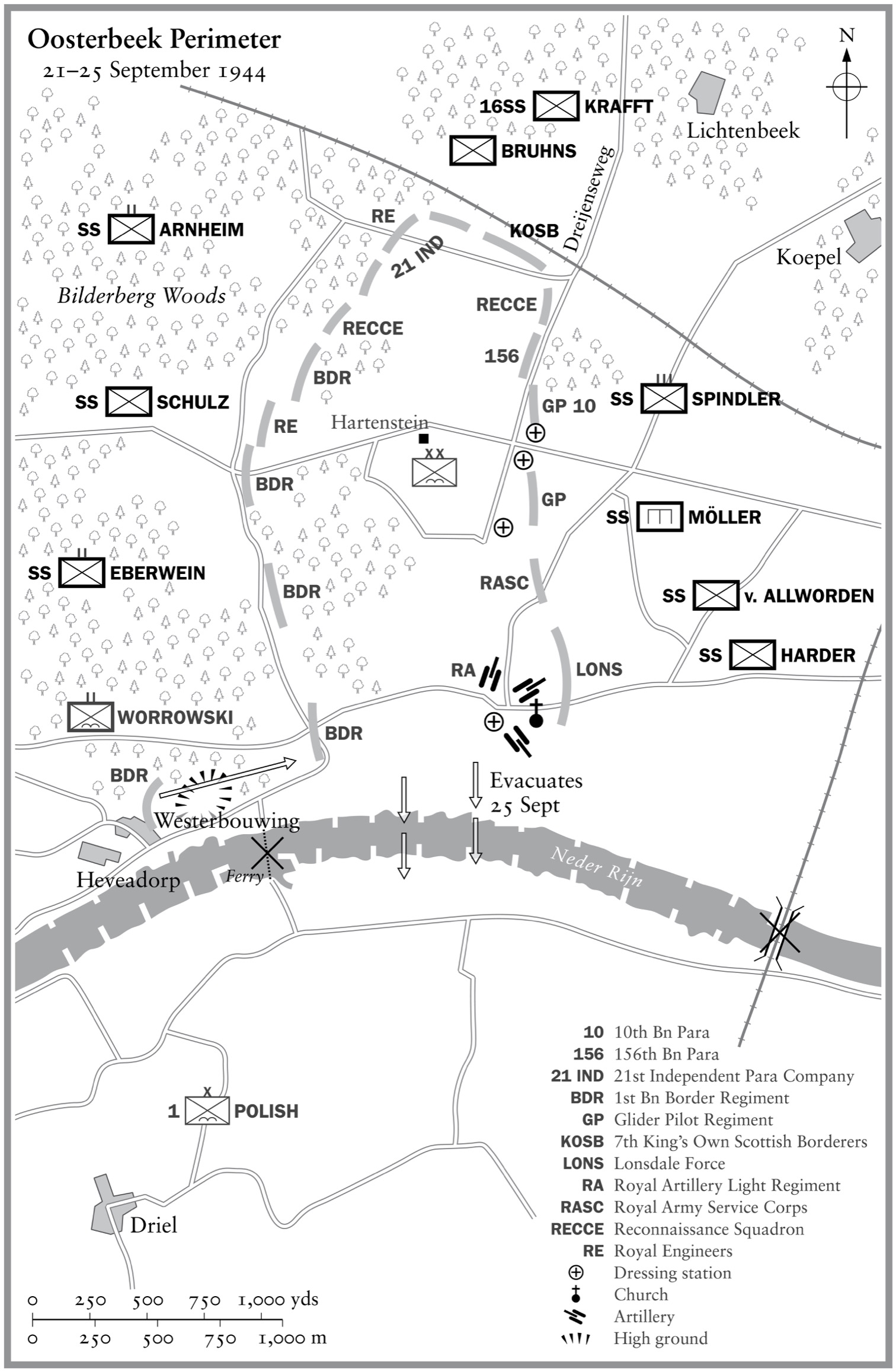

The 4th Parachute Brigade under Hackett had still not yet managed to reach any form of safety after their bruising battle the day before against the Hohenstaufen blocking line along the Dreijenseweg. The survivors of the 10th and 156th Parachute Battalions were at less than half their strength. With brigade headquarters, they prepared defensive positions south of the railway line. Hackett wanted to push on east to Oosterbeek during the hours of darkness, leaving before midnight, but General Urquhart told him to stay where he was and make his move after dawn.

Hackett was right to be concerned. Urquhart evidently had not known that the Border Regiment had pulled back its company from the key crossroads to the south which Hackett’s force would need to use. During the night, the Germans moved in and took up positions in that area both on the Wolfheze road and around where the Breedelaan reached the Utrechtseweg. So when the 156th Battalion led off next morning, it had a fearful fight against infantry and assault guns to clear a way through. From 270 men, the battalion was reduced to just 120 men still capable of fighting.

With pressure building up from the Kampfgruppe Krafft to the north and from Kampfgruppe Lippert’s SS Unteroffizier Schule Arnheim to the west, Hackett’s force was almost surrounded. He ordered the 10th Battalion to strike off to the north-east, which seemed the only way out. But in the woods contact was lost, and Hackett found himself moving with just the remnants of the 156th Battalion, his headquarters and a sapper squadron.

Sheltering in a ditch, Major Geoffrey Powell saw Hackett run through enemy fire to where three Jeeps stood. One was ablaze, another next to it was packed with ammunition and the third had a trailer with the badly wounded Lieutenant Colonel Derick Heathcoat-Amory strapped to a stretcher. Hackett leaped into the driver’s seat, shielding his face from the flames, started the Jeep and drove it out of range, thus saving the wounded man’s life. Powell thought Hackett deserved a VC. Heathcoat-Amory, the head of the Phantom detachment with a direct radio link to the War Office, was later Harold Macmillan’s chancellor of the exchequer.

Further on the enemy fire was so strong that when Powell and the remnants of the 156th Battalion found a large crater in the woods they slipped into it and took up all-round defence. With the other brigade personnel, they were about 150 strong. It was less than a thousand metres from the Hartenstein and safety, but German strength was increasing. Staff Sergeant Dudley Pearson, who was Hackett’s chief clerk, found himself next to a terrified young soldier who just fired his rifle vertically in the air. Exposed to mortar fire, their losses were heavy, especially among officers. Pearson also saw one collapse beside him, shot with a bullet through the throat. The commanding officer of the 156th, Lieutenant Colonel Sir Richard Des Voeux, was killed, so was his second-in-command Major Ernest Ritson, and Hackett’s brigade major.

After the defenders had held off German attacks for most of the afternoon, Hackett announced that they were going to break out by charging straight through the German line towards British positions some 400 metres away. Powell agreed that, however suicidal it might appear, it was certainly better than staying there to be picked off as their ammunition ran out. ‘So we lined up on the rim of the hollow and waited for Hackett to order us forward.’

Hackett first went to say goodbye to the wounded whom they had to leave behind. A corporal refused to come. He insisted on remaining so that he could give them covering fire. When their cavalry brigadier shouted ‘Charge!’ the paratroopers burst out screaming and shouting, and firing their Sten guns. Pearson saw Hackett, also armed with rifle and bayonet, pause above one cowering young German soldier, change his mind and push on. The astonished Germans in front of them scattered and, with the loss of half a dozen men, the remaining ninety broke through to positions held by the Border battalion from the airlanding brigade. The 10th Battalion, bringing their wounded commanding officer, Lieutenant Colonel Smyth, also reached the Hartenstein perimeter. But they too were down to about seventy men, close to a tenth of their original strength.

The 21st Independent Parachute Company, reinforced by sixty glider pilots and a troop of airborne sappers, fought back against the Luftwaffe Kampfgruppe from Deelen backed by assault guns. They were a kilometre due north of the Hartenstein, and based themselves on a large house called Ommershof. The Germans had crossed the railway line during the night and were hoping to slip through to cut them off. The inexperienced Luftwaffe conscripts were facing some formidable fighters, including the German-speaking Jewish pathfinders, who had no intention of giving ground. A German officer approached shouting, ‘Hände hoch!’, demanding their surrender. The commander of the sapper detachment told his men to hold their fire, but then hurled back abuse when the German continued to demand their submission. A burst of Bren-gun fire made the irritating man dive for cover, and the battle continued.

Late in the afternoon, during a slight lull after another attack, the defenders were surprised to hear music through the trees. A German loudspeaker van was playing Glenn Miller’s ‘In the Mood’. The paratroopers were even more amused when it was replaced by a voice calling to them in English. ‘Gentlemen of the 1st Airborne Division, remember your wives and sweethearts at home.’ It then tried to claim that many of their senior officers, including General Urquhart, had been captured, so it was perfectly honourable for them to surrender. This provoked catcalls and insults and whistling, then firing. ‘Stayed in position all day,’ wrote a paratrooper called Mollett. ‘Plenty of mortaring and sniper fire, so made myself a humdinger of a little trench . . . Got another cert when a bunch of Jerries came right out into the open in front of us, also several possibles. Heard a mobile speaker in the distance – funny shooting Jerries to dance music.’

A little further down the railway track towards Arnhem were the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, minus two companies cut off during the retreat from the landing zone. They were dug in around the ‘White House’, the small Hotel Dreijeroord. Colonel Payton-Reid, who had felt so embarrassed on being welcomed there as a liberator, could only prepare for one of the most devastating battles in the regiment’s history. They were facing a reinforced Kampfgruppe Krafft, backed by tanks and assault guns. On Wednesday 20 September, the Borderers held off the probing attacks without too much difficulty, but the real fight would come on the morrow.

On the western side the Border Regiment, which up until now had not seen heavy fighting, became involved in several different battles as the SS Kampfgruppe Eberwein advanced. The withdrawal in front of Division von Tettau had meant abandoning the Wolfheze Institute, where an SS-Hauptsturmführer was convinced that a British general was being secretly treated. When Dr van de Beek denied this, a gun was thrust into his back. ‘If you are lying, it will cost you your neck.’ Still at gunpoint, Dr van de Beek had to give the SS a guided tour of every room in the Institute. No general was found, so the Germans took away a British military chaplain who had been helping tend the wounded.

The companies of the Border Regiment were clearly too spread out as the retreat gathered speed on the Tuesday. Three of them were pulled back and brought closer together over a front not much more than a kilometre and a half wide, running south from the Utrechtseweg. But as the woods were quite dense, there was little communication. The Borders had to dig in well because the mortar stonks came in suddenly to catch men out in the open. And because there were gaps between the three companies, small groups of SS and even a tank managed to filter through. One of the few remaining 17-pounder anti-tank guns, directed in person by Colonel Loder-Symonds, destroyed it conclusively. D Company had been reinforced with some RAF radar operators who had never fired a rifle before. So ‘our RSM walked up and down the parapet of their trench’, wrote the company commander, ‘giving them weapon training instruction during the battle.’

A Company was on its own, between the railway line and the Utrechtseweg. With a platoon of glider pilots on its right, it faced Lippert’s SS Unteroffizier Schule Arnheim, probably the best unit in the Division von Tettau. A glider pilot lieutenant called Michael Long bumped into a German soldier at close quarters in dense undergrowth. They both shot at each other at point-blank range, the German with a sub-machine gun, and Long with his Smith and Wesson revolver. Long, shot through the thigh, was the more badly wounded. He had only managed to hit the German’s ear, so the immobilized lieutenant became the prisoner. The German bandaged his leg, and Long bandaged his head. Then the German’s platoon commander, Oberleutnant Engelstadt, arrived. He and Long chatted pleasantly about where they had fought in the war. Engelstadt had been in Italy, Russia and the western front. Long asked which he had preferred. Engelstadt glanced round at his men, then bent down with a grin on his face. ‘The west,’ he replied. ‘Anything’s better than Russia.’

While the perimeter was starting to close during the latter part of Wednesday, many inhabitants of Oosterbeek tried to escape. They took what they could carry and fashioned crude white flags, often just a handkerchief or napkin tied to a stick.

A Polish war correspondent in the woods south of the Amsterdamseweg was approached by women in tears, asking where they could possibly go to escape the fighting. ‘We heard a great scream above the thunder of the artillery,’ he wrote. ‘A large group of children came running through the trees and tried to make their way across the uneven terrain, falling and getting up again. There were more than ten of them led by a girl of about sixteen: the eldest of the children no more than ten years old and all running after her.’ Those civilians who decided to stay either moved mattresses down into their cellar if they thought it strong enough, or sought shelter with neighbours. Many found that ‘the Tommies’ wanted to come in for a wash and a cup of tea and a little rest. But even those who had filled their baths to the brim feared that water might soon be a major problem.

In the middle of the northern part of the perimeter, the Hotel Hartenstein was losing its elegance by the hour. Paratroopers ripped the shutters off to provide covering for their trenches. German shells had already started to break open the roof, and smoke from burning Jeeps blackened the white walls. The large and solid figure of General Urquhart brought reassurance to many, but there was not very much he could do now that they were trapped. The sad remnants of his division would hold on in the hope that if they maintained their bridgehead north of the Rhine, then the Second Army could use it as soon as they had cleared their way from Nijmegen through the polderland of the Betuwe, or the ‘Island’.

The American forward air controller with the 1st Airborne, Lieutenant Paul Johnson, reported how they came under heavy mortar fire. An RAF sergeant helping the team was killed. He and his men were well dug in, but their vehicles and equipment remained exposed. ‘As the shelling grew heavier the rest of them practically lived in their slit trenches.’ He thought the radio operators behaved bravely under fire, considering it was the first time they had been in combat.

Since there was little he could do outside the Hartenstein, the other American lieutenant, Bruce Davis, went out on patrol at night. ‘Three of us went after a machine-gun nest and found it about four hundred yards from divisional headquarters. There were six men sitting by it doing nothing. We threw two grenades and then went back. On the way back I shot a sniper, who fell about twenty feet out of a tree, hit in the head. I think that was one of the most satisfying sights I have ever seen. He was either careless or over-confident, for he had chosen a tree higher than the others and not very thick with foliage, and making a beautiful target. He did not even see me.’

Encirclement at Oosterbeek by SS forces represented an even greater danger to the many Dutch volunteers assisting the British. One of the most remarkable was Charles Douw van der Krap, a naval officer, who had fought in the defence of Rotterdam against the German invasion in 1940. He had been imprisoned by the Germans in a camp in Poland, from which he had recently escaped to take part in the early phase of the Warsaw Uprising. Reaching Arnhem just before the airborne landings, van der Krap was ready to offer his services at the Hartenstein. Lieutenant Commander Arnoldus Wolters, a Dutch liaison officer who knew of him by reputation, asked him to turn some forty Dutch volunteers into a company. But, because of the shortage of weapons and ammunition, their main task was to retrieve supplies parachuted behind German lines.

Douw van der Krap longed to hit back at the Germans but he did not believe that the British could win, and that would mean the sacrifice of these brave young men for little advantage. ‘The British would be taken prisoner, the Dutch boys would be shot on the spot,’ he explained to Urquhart’s intelligence officer, Major Hugh Maguire. Maguire listened carefully and had to agree with his pessimistic assessment. The young volunteers were told to disband and go home. The majority left with great reluctance, yet a number insisted on fighting to the end, while several more went to work in one of the improvised hospitals.

While the British were surrounded they also held a considerable number of German prisoners, who were placed in the hotel tennis courts under guard. The regimental sergeant major in charge of them was astonished to see how few of them were wounded, ‘which annoyed me at the time as we were getting it outside the courts’. It was perhaps confirmation of the renowned accuracy of German mortar teams. The prisoners’ rations handed to a German officer were exactly the same as those the British were receiving. ‘The portion worked out to half a biscuit and about a sixth of a sardine per man. This was done with great care and each German filed by to collect some. They were very sullen about it.’

When the Hartenstein came under heavy mortar fire that day, one of Bruce Davis’s American radio operators was hit. Colonel Warrack drove him in a Jeep straight to the dressing station at the Hotel Schoonoord, but while he was still there the Germans overran the hospital. To avoid becoming a prisoner Warrack hurriedly ‘removed his tabs and badges of rank, and worked as a private’. Warrack, a large cheerful man, was not easy to conceal, but he got away with it.

The southern road to Oosterbeek church was not the only route left open following the retreat from the battle round the St Elisabeth Hospital. A kilometre or so to the north, a group of South Staffords arrived out of breath at the crossroads in Oosterbeek by the Schoonoord. Many stragglers claimed to have panzers right behind them to justify their panic, but the appearance of three German tanks proved they were not exaggerating. A troop from the 2nd (Airlanding) Anti-Tank Battery was fortunately present and managed to fight them off.

The attackers came from Kampfgruppe Möller. According to Hans Möller, the British 6-pounder anti-tank gun they came up against also killed Obersturmbannführer Engel at the head of his company. There was little left of him from the direct hit. Möller’s pioneers from the Hohenstaufen now had some 20mm light flak guns, two tanks and an assault gun supporting them. These vehicles quickened their advance around the Utrechtseweg by flattening garden fences. The Kampfgruppe had also been reinforced with RAD, Kriegsmarine and Luftwaffe personnel. They had no training in street fighting, ‘but those that survived, soon learned’.

Demands to surrender were ignored, Möller wrote later, ‘or answered with caustic remarks, such as “focken Germans”’. He claimed that the British also gave more ‘humorous answers over loudspeakers’ by playing ‘Lili Marlene’ or ‘We’ll Hang Out our Washing on the Siegfried Line’. But there was no doubt about the intensity of the fighting. ‘Anyone who was rash enough to venture to look out of a window, would be found with a hole in his head.’

Despite the heavy gunfire outside the Schoonoord, the volunteers carried on washing patients using a bucket and soap. Kneeling by their patient, they threw themselves flat at each explosion. The wounded who were not completely incapacitated put on their netted parachute helmets, which looked incongruous in bed. According to Hendrika van der Vlist, one of the British doctors announced that patients must take care of the medical cards attached to their battledress, because all their medical details were recorded there. ‘You mustn’t lose it,’ he joked, ‘otherwise the wrong arm or leg might be amputated.’ This apparently raised a big laugh.

Suddenly, shouts came from the hotel kitchens. Some of the Jews who had been released from the prison in Arnhem had been in the hotel kitchens chatting with a few of the walking wounded and orderlies. Being unaware of the Nazi racial persecution, the British soldiers could not understand why they had been locked up just for being Jewish. They knew astonishingly little of the Nazis’ racial policies. In the middle of this conversation, a Waffen-SS officer appeared. He pointed his gun at one of the British medical orderlies and shouted: ‘Weapons. Do you have weapons?’ He then pushed open the swing doors through to what had been the dining room and was now another ward.

This huge officer appeared in the doorway in full combat kit. He had black stubble, an unwashed face and a Waffen-SS camouflage jacket. According to Hendrika van der Vlist, he looked around with glittering eyes. Other Germans followed. All the British medical orderlies raised their hands in the air. None of them were armed. While this was happening, the Jews escaped from the house through a back door. Sister Suus entered the dining room, and took the threatening German by the arm. She said very calmly. ‘This hospital has just been shot at.’

‘No, Sister, no!’ he replied. ‘We’re not like the Americans. We don’t shoot at a hospital.’ She pointed to the bullet holes in the wall. He quickly insisted on seeing his wounded compatriots. A British doctor came over, and Hendrika van der Vlist accompanied them to translate. The British doctor pointed out the German wounded. The German officer shook the hand of the first one and congratulated him on being free again. He asked how he had been treated. There was a note of challenge in his voice. Hendrika did not think that the wounded German looked delighted at the announcement of his liberty. He just replied that he had been very well looked after. According to Colonel Warrack, who was watching incognito, there could have been one exception, through no fault of the medical staff. An ardent young Nazi had refused morphia and any help for four hours. He had a shattered knee joint and must have been suffering considerably. ‘Eventually he gave in shouting “Kamerad!” and allowed himself to be treated.’

The officer also insisted on seeing the operating theatre, where a German soldier was undergoing minor surgery. On looking at his compatriot, he suddenly said, ‘Muss das sein?’ – ‘Does this have to be?’ – as if the war was simply an unfortunate misunderstanding with tragic consequences. German officers often tried to claim that they had never wanted the war. ‘Wir haben es nicht gewünscht.’ It had been forced on them. The commanding officer of the field ambulance, the imperturbable Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Marrable, still puffing gently on his pipe, said to his staff, ‘Good show, chaps. Don’t take any notice of the Jerries. Carry on as if nothing has happened.’

The sudden German advance in eastern Oosterbeek posed another serious problem. It made it much more dangerous to transport the wounded from the Schoonoord to the surgical department in the Hotel Tafelberg, though such transfers were still possible when the firing was less intense. As a result one of Marrable’s doctors had to take off a soldier’s shattered foot with an escape file for sawing through prison bars as all the amputation saws were in the Tafelberg on the other side of the front line.

The Hotel Vreewijk, just across the road from the Schoonoord, had been turned into a post-operative centre, but soon it was much more. A courageous young woman called Jannie van Leuven arrived with a horse and cart loaded with wounded men, whom she had collected and then driven through firefights. Her clothes were so soaked with the blood of the wounded she had cared for that she was given battledress, which she wore until they were all captured later. Although the Schoonoord was clearly marked with many Red Cross symbols, the machine-gun fire continued and an assault gun fired four rounds into the building. The wide windows at the front of the hotel were ‘gaping holes bordered by wicked glass stilettos’. The utterly vulnerable wounded could do little but pull their blankets over their faces as a defence against flying glass, which made them look a little like children trying to hide under the bedclothes. Mortaring was constant and several men were re-wounded by shrapnel. Plaster dust covered the faces and heads of the staff as if they had been in a fight with flour bombs. Both Dutch volunteers and Royal Army Medical Corps personnel were astonished at how uncomplaining their patients were, showing little more than ‘the mirthless grin of pain’.

The fighting in both Arnhem and Oosterbeek caused deep mental wounds as well. Psychological breakdown from combat fatigue could produce many strange forms of behaviour. One man, although hardly wounded physically, would take off all his clothes and walk round the room, pumping his arms and making noises like a locomotive. From time to time, he would utter a string of curses and say, ‘Blast this fireman, he was never any good.’ Another casualty would wake people at night, bend over them and stare into their eyes to ask, ‘Have you got faith?’ At the St Elisabeth Hospital, Sister Stransky had a strange encounter with a case of German combat fatigue. A Wehrmacht soldier appeared armed with a pistol. Sister Stransky, a Viennese, refused to allow him to come in. He kept repeating to her, ‘I have come all the way from Siberia with a new weapon to rescue the Führer.’ When still refused entry, he sat down on the steps of the hospital entrance and began sobbing. Some died with great calm. A sergeant who knew he was dying said to a medic, ‘I know I’m not going to live. Would you please just hold my hand.’

The main German attack that day was aimed against the south-east corner, on the lower road towards Oosterbeek church. Colonel Thompson had asked for some more officers to help get the sector organized for defence, and he was sent Major Richard Lonsdale, the second-in-command of the 11th Parachute Battalion. Lonsdale, an Irishman who had won the Distinguished Service Order in Sicily, was the officer who had been wounded in the hand by flak shrapnel just before jumping. He went forward to sort out the defence line, about a kilometre in front of Colonel Thompson’s howitzers.

Suddenly a soldier shouted, ‘Look out, they’re coming!’ Lonsdale saw three German tanks coming out of the woods on to the road some 300 metres away. Infantry were also advancing behind a self-propelled assault gun. Lance Sergeant John Baskeyfield of the South Staffords was in command of a 6-pounder anti-tank gun. He and his crew destroyed two tanks, in each case by waiting until they were within a hundred yards. Baskeyfield, although wounded badly in the leg, and alone after the other crew members had been killed or wounded, carried on loading and firing. In a renewed German attack, his 6-pounder was knocked out, so he crawled across to another, the crew of which had all been killed. Baskeyfield manned it single-handed and, firing two shots, knocked out another self-propelled assault gun. ‘Whilst preparing to fire a third shot, however, he was killed by a shell from a supporting enemy tank.’ Baskeyfield was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

A little later flamethrowers set off a panic, and one group of South Staffords who broke and ran had to be rounded up by an officer and ordered back into the line. The Germans renewed their attacks several times that afternoon. At one point a German self-propelled assault gun was tucked in on the far side of one house, so Major Robert Cain spent a considerable time playing a form of deadly pétanque, firing PIAT bombs over the top of the roof on high elevation as if it were a mortar. A gunner officer, Lieutenant Ian Meikle, bravely clung on behind the chimney above, trying to guide him on to his target. It cost Meikle his life when a German shell hit the chimney, while the constant firing of the PIAT perforated Cain’s eardrums.

Two tanks appeared and Cain engaged them too with his PIAT. Wanting to make sure that the one he had hit was properly knocked out he fired again, but this time the PIAT bomb exploded in the launcher. ‘There was a flash and the major threw the PIAT in the air and fell backwards,’ a glider pilot sergeant reported. ‘Everyone thought he had been hit by a shell from the tank exploding. He was lying with his hands over his eyes. His face was blackened and swollen. “I think I’m blinded,” he said.’ His face was riddled with tiny metal fragments. They lifted him on to a stretcher and he was carried away. At the aid station, his sight returned, so after a short rest he discharged himself and went back. He soon heard a cry of ‘Tigers!’, so he ran to the 6-pounder anti-tank gun. Cain called to another soldier to help him and they achieved a first-round hit, which brought the tank to a halt. ‘Reload!’ Cain shouted. ‘Can’t, sir,’ came the reply. ‘Recoil mechanism’s gone. She’ll have to go into the workshops.’ Cain clearly appreciated the calm and professional answer.*

Towards evening, Lonsdale was given permission to pull back to the church with the remnants of the three battalions. As most of them recovered in the battered church, Lonsdale, head bandaged and arm in a sling, went up into the pulpit and addressed them in stirring style. Thompson Force was officially redesignated Lonsdale Force the next day. The 1st and 3rd Battalion men were positioned south of the church on the polderland stretching down to the river, with the South Staffords around the church and the 11th north of the road. Company Sergeant Major Dave Morris of the 11th moved into the Vredehof, or Peace House. The door was barricaded with two pianos, so they climbed in through a window. In the cellar they found fifteen civilians, including three children and a month-old baby. Rather surprisingly, the owner of the Peace House, Frans de Soet, begged a rifle off the paratroopers, and he joined CSM Morris in the attic next day, sniping from a skylight.

Back in England, Major General Sosabowski’s Polish Independent Parachute Brigade suffered agonies of impatience and frustration. They had watched the first wave take off on the Sunday. Lieutenant Stefan Kaczmarek thought it looked so powerful that he felt ‘a joy that almost hurt’ at the idea that the war would soon be over. But then, after two days of cancellations, Sosabowski and his officers became understandably angry at the lack of information. They had already been to the airfield once and been sent back.

At 08.45 hours on Wednesday morning, Lieutenant Colonel George Stevens, the 1 Airborne Corps liaison officer with the Poles, brought a new order. They were not to land near the Arnhem road bridge, but to the west near the village of Driel. If the Arnhem bridge was still in airborne hands, they wondered, then why were they being dropped well to the west? They began to suspect that things had gone badly wrong. All Colonel Stevens would say was that the brigade was to be dropped south of the Neder Rijn and was ‘to cross by means of the ferry’.

Sosabowski briefed the battalion and company commanders on the new plan, and the brigade emplaned for a 12.30 take-off. This was delayed another hour. But ‘after having started engines, take-off [was] again postponed for 24 hours because of bad weather.’ A report from the First Allied Airborne Army implied, however, that the real reason for this cancellation was to give priority to supply drops, but in the event ‘most of the supplies dropped to the 1st Airborne Division fell into enemy hands.’ ‘The soldiers, exhausted by a whole day of tense anticipation, return to the camp, embittered,’ a Polish paratrooper wrote. ‘In the evening they gather around radio receivers to hear news from Warsaw – now dying – which had awaited their help.’

That evening at 22.00, Colonel Stevens returned to say that the ‘position was desperate’. The 1st Airborne Division urgently needed reinforcements as it was surrounded. Communications with the continent had clearly not improved, as Stevens thought that the northern part of Nijmegen and the bridges there were still in German hands. He admitted that the present state of affairs was ‘entirely different from the one anticipated’. He did not need to add that the role of the Polish brigade was now simply to help pull British chestnuts out of the fire. That was all too plain.

Sosabowski, who had never had any confidence in the whole plan for Market Garden, now lost his temper. He had consistently objected to the fact that his anti-tank guns would be landed by glider with the British on the north side. Now that the Germans held the Arnhem bridge, it meant that his brigade would be dropped on the south bank, without any anti-tank defence. Sosabowski told Stevens to inform First Allied Airborne Army headquarters that if he did not receive a proper briefing on what was happening at Arnhem, he would not go. He said that General Brereton should be ‘asked to make a decision. He [Sosabowski] maintained that the former task being cancelled, the introduction of the Brigade Group into battle should be preceded by adequate information regarding own troops and enemy position.’ An hour later, Colonel Stevens discovered that General Brereton was somewhere on the continent, but even his own headquarters did not know where, and General Browning had not been in touch for more than twenty-four hours. It was hardly surprising that Sosabowski despaired of his superior officers.