19

Nijmegen and Hell’s Highway Thursday 21 September

On the German side, confusion continued all through the night over whether German troops were still fighting in Nijmegen, south of the Waal road bridge. Bittrich reported to Model’s headquarters, ‘no further report has been received from the bridgehead for the last two hours, garrison appears to be destroyed.’

Hauptsturmführer Karl-Heinz Euling had commanded the defence of the Valkhof and Hunner Park partly from the Belvedere tower, and partly from a house near by. The fighting had carried on well after Sergeant Robinson’s troop had charged across. And yet around midnight Euling had somehow managed to escape with almost sixty of his men as well as with a small group of Fallschirmjäger under Major Ahlborn.

Euling claimed that the collapse of buildings in the raging fires gave the impression that he and his men had perished. In fact they had climbed down the steep hill of the Valkhof and gone under the bridge while more British tanks thundered across above them. They were in darkness down below because the Valkhof bluff shielded them from the fires in the town above. Euling had then led his men in single file down the street ‘in a casual manner, as if they were Americans’. Euling asserts that he and his men pushed along the riverbank to the east of Nijmegen, where they found boats and crossed over to the north bank of the Waal. Since both the Americans and the underground had searched and found none, this seems unusually fortunate.

While Euling and his SS panzergrenadiers were greatly admired for their bravery, a reserve unit under Major Hartung on the north bank had apparently ‘dispersed without orders’ on the appearance of the British tanks. They had run back to Bemmel and even as far as Elst, where they were rounded up by part of the 10th SS Panzer-Regiment and brought back into line, no doubt at gunpoint. By dawn on 21 September, II Panzer Corps reported that a defence line had been established running from Oosterhout to Ressen and on to Bemmel, blocking the Allied advance less than four kilometres north of the road bridge. This line was stiffened with some Mark IV tanks which had been ferried across at Pannerden. These forces were supported by the Frundsberg artillery regiment also at Pannerden. Harmel transferred his command post to the ferry point, because supplies were not getting across in sufficient quantities.

Despite Generalfeldmarschall Model accepting responsibility for the failure to blow the bridge, Generaloberst Jodl noted that Hitler was still raging about ‘the idiocy of allowing undemolished bridges to fall into enemy hands’. Generalmajor Horst Freiherr von Buttlar-Brandenfels of the Wehrmacht high command continued to demand more details to account for ‘why the Nijmegen bridge was not destroyed in time’. Model’s chief of staff had to explain that the order had been given immediately after the first Allied landings. The situation at Arnhem had shown that this order was entirely justifiable. If the bridge at Arnhem had been blown, it would have been impossible to reinforce Nijmegen. And as for the bridge at Nijmegen, that could always be recaptured with an attack from the east by the II Fallschirmjäger Corps.

Both British and American commanders were conscious of the danger. On Brigadier Gwatkin’s orders, M-10 tank destroyers from the 21st Anti-Tank Regiment followed on in the early hours, just behind the first company of the 3rd Battalion Irish Guards. Captain Roland Langton with a squadron of their tank battalion was also on the way, but in the dark they had trouble finding the infantry from their 3rd Battalion. Despite their casualties from the day before, Major Julian Cook’s battalion pushed forward at dawn with the tank destroyers in support for another kilometre. ‘Every inch of this advance was hotly contested,’ Cook wrote. ‘The Krauts had all the advantages. They controlled the orchard, the ditches, the farmhouses etc.’ Cook and his men had hit Harmel’s defence line. They could do little more until the Irish Guards group was ready to deploy.

With the fighting across the Waal and the counter-attacks from the Reichswald, the 82nd Airborne’s casualty rate over the last twenty-four hours rose to more than 600 men in need of hospital treatment. The 307th Airborne Medical Company had just created a casualty clearing station out of a former monastery in a southern suburb of Nijmegen. The paratroopers called it ‘the Baby Factory’ because SS soldiers were thought to have mated there with racially selected young women.* Locals joked that this Strength through Joy centre should be called the ‘Lustwaffe’.

The American doctors and medics were greatly assisted by large numbers of women volunteers. They had to cope with one aid man drinking the surgical spirit used for sterilizing medical instruments, and American paratroopers desperate for souvenirs to send home. One GI kept offering a Dutch nurse more and more money for her Red Cross brooch. She was, however, shocked by the racial tensions in the US Army. Whenever she looked after black soldiers from a quartermaster battalion, a white soldier would make a snide comment: ‘Is that your new boyfriend?’

That day the 307th was able to send some casualties back by road to the 24th Evacuation Hospital at Leopoldsburg over the Belgian frontier. This solution did not last once the Germans started attacking Hell’s Highway in earnest. The company, which had been reinforced with an extra group of surgeons, was certainly hard-worked. It carried out 284 major operations and 523 ordinary operations. As one might expect, 78 per cent were ‘extremity cases, hands, arms, feet and legs’.

The 307th’s mortality rate in the circumstances was impressively low at just 2.5 per cent. Military medicine had made huge advances since the First World War, with penicillin, glucose drips, oxygen, anti-tetanus, sulfa powder and improved anaesthetics. Rapid evacuation by Jeep also made a difference. The company’s doctors encountered only a single case of gas gangrene, a casualty who did not arrive until thirty hours after his injury. The old triage system from the previous war, which left those with major head and stomach wounds to die, was largely replaced. The ‘usual procedure followed was to admit seriously wounded to the shock room directly from the admitting room’. The use of a total of 10,000 gallons of oxygen and 45 million units of penicillin sodium made an enormous difference. So did blood transfusions. ‘Blood was a major factor in saving the shock cases and most of the ones with massive hemorrhages,’ the 307th report stated. As well as using 1,500 units of plasma, the team supplemented their blood bank by calling on lightly wounded patients to act as blood donors.

Sergeant Otis L. Sampson, who had been badly hit by 88mm shrapnel, was taken to the Baby Factory by Jeep. ‘I was carried into the hospital on a low legged stretcher’, he recorded, ‘and deposited on the floor in the hallway. Here I was given two quarts of blood: I could feel life flow back into my body. A major looked me over and told an attendant to take my clothes off and turn me on my back. I informed him, “Major I’m hit in the back.” “I know,” he said, “but your stomach is where the shrapnel is. If this was World War I, with the wound you have, you wouldn’t survive. You can have a drink of water if you care to, it won’t do you any harm.”’

The attendant tried to walk off with his paratrooper jump boots, saying, ‘Where you’re going, you won’t need them.’ An outraged Sampson tried to crawl off the stretcher to stop him so the major ordered the attendant to bring them back. In the ward, Sampson watched the doctors draw the sheet over the faces of those who had died. But not all patients were badly hit. A German pilot had parachuted from his plane and he came down in sight of their window. ‘His chute had been caught on some object and he was left dangling.’ Two paratroopers, both walking wounded, immediately went out to relieve the pilot of his watch and pistol.

The German pilot was from one of the fighters which had attacked Nijmegen in the early afternoon, causing a sudden panic. The remaining population thought that the city was about to be bombed like Eindhoven, and crammed into the closest air-raid shelter. The fighters also machine-gunned the Baby Factory. When Captain Bestebreurtje went there to have his wounds dressed, the doctor said to him, ‘Do you know what those German bastards did? They flew over and strafed the hospital in spite of the fact that we have a big red cross on it. And do you know what I was doing when they came over? I was saving the life of a German – and I happen to be a Jew.’

After the battle of the Nijmegen bridges, there was a great deal of clearing up to do. Many were struck by one image. On the road bridge on the Nijmegen side a dead German in rigor mortis had an arm outstretched which appeared to be pointing across the river. Altogether eighty dead Germans were found on the bridge, and ‘during the morning’, wrote Lieutenant Tony Jones of the Royal Engineers, ‘a great many more prisoners were winkled out – an extraordinary assortment, old and young, SS, police, Wehrmacht, Marines, some temporarily arrogant (but only for a short time), but most completely dazed and bewildered. The equipment captured and lying about was even more varied – 88mm guns, 50mm, 37mm, a baby French tank, Spandaus, Hotchkiss machine-guns, new rifles and old 1916 long barrel and long bayonet rifles, mines and bazookas, grenades of every sort, size and description. It was almost a foundation for a War Museum.’

In Nijmegen itself, the conditions were far worse with much of the northern part of the town burned out. ‘The city looks awful and is heavily damaged,’ the director of the concert hall wrote. ‘Many burned blocks of houses, craters in the roads, mountains of glass and rubble, uprooted trees, a terribly sad sight.’ The great De Vereeniging concert hall itself had more than a thousand windowpanes broken.

All around the Valkhof the destruction was of course even more terrible, ‘a chaos of shelled trenches, bits of uniform, dried pools of blood, shot-up vehicles and weapons’. German bodies were still lying in the street, some covered with coats. According to one eyewitness, Americans were wandering laconically amid the scene. ‘One American paratrooper was eating his lunch out of a tin next to the body of a German soldier.’ Wounded civilians were taken to the St Canisius hospital ‘where they were being operated on eight or ten at a time’. People in villages, having heard of the destruction inflicted on Nijmegen, immediately donated what they could, especially food, to help those who had lost everything.

Out of 540 Jews in Nijmegen in 1940, only sixty or so were left four years later. Simon van Praag had been hidden by a Catholic priest and had to spend much of the time in the dark to evade discovery or denunciation. To remain concealed while the battle raged and houses were set on fire must have been terrifying. There was little relief when the ordeal ended, and he emerged into daylight to see the city half-destroyed from the fighting.

Although artillery shells were still landing in Nijmegen, the final departure of the Germans meant that the Dutch red, white and blue flag came out again and the purges recommenced. ‘Prostitutes who served members of the German occupation forces’, wrote Cornelis Rooijens, ‘have their hair cut off with big shears and are wrapped in pictures of prominent Nazis at the hands of the city rabble and professional idlers.’ And Martijn Louis Deinum also saw captured members of the NSB paraded, including ‘a woman with a portrait of Hitler hanging round her neck and with a completely shaven head’. Many disliked these forms of revenge, while others rather resented the way that British soldiers tried to interfere. ‘Generally speaking they don’t have the same hatred of the Germans as we have,’ a woman wrote. ‘I told them that they could not imagine what these years had been like for us. They think that the shearing of the heads of those who have had relations with the Germans is so awful, that whenever they have a chance, they will try and stop it.’

By 11.00 that morning, Model’s headquarters heard that ‘so far 45 enemy tanks have crossed over the bridge towards the north.’ These presumably were a mixture of Q Battery tank destroyers and Irish Guards Shermans. Brigadier Gwatkin had told the Vandeleur cousins that they were to advance at the normal speed of an approach march, fifteen miles in two hours. But they could see immediately that the dyke embankment, with a road along the top and flanked by boggy polderland, ‘was a ridiculous place to operate tanks’. An advance on a one-tank front, with no chance of manoeuvring off the road, would be suicidal. But of course they had no option but to follow orders. Montgomery’s refusal to listen to Prince Bernhard’s advice and the failure of planners to consult army officers from the Netherlands army had been a major mistake.

At 10.40, Captain Langton was ordered to advance twenty minutes later, although the Irish Guards war diary indicates that finally they did not advance until 13.30. Langton thought at first that Lieutenant Colonel Giles Vandeleur was joking. All they had was a road map. The order came, ‘don’t stop for anything.’ Langton was furious when the Typhoons he had been promised failed to appear. In fact they had come, but communications had broken down.

‘The Typhoons had begun arriving, a squadron at a time,’ the forward air controller, Flight Lieutenant Donald Love, recounted. ‘[Squadron Leader] Sutherland tried to contact them but the VHF set in the contact car had gone dead. It was absolutely horrible . . . The Typhoons were milling around overhead and on the ground, shelling and mortaring was going on. I felt frustrated and exasperated. There was nothing to be done. The Typhoons had strict instructions not to attack anything on speculation.’ Love’s mood was not improved when their RAF radio operator suffered a nervous collapse.

The four leading Shermans were knocked out one after another. The first three ‘within a minute’. As another Guards officer put it, they were lined up ‘like metal ducks in a fairground booth waiting to be shot down’. The defence line contained 88mm guns, self-propelled assault guns and at least two Royal Tigers hidden in woods. Giles Vandeleur shouted across to his cousin that if they sent any more tanks up the road ‘it would be bloody murder’.

Langton, left with just four Shermans in the squadron, was joined a few minutes later by Colonel Joe Vandeleur, who arrived with his cousin Giles. Langton asked whether they could get air support. Vandeleur shook his head and told him quite inaccurately that all aircraft were being tasked to support the drop of the Polish Parachute Brigade. ‘But we could get there if we had the support,’ Langton persisted. Vandeleur again shook his head and said that he was sorry. He ordered Langton to stay where he was until further orders. According to Flight Lieutenant Love, Colonel Joe Vandeleur then went off on foot into the woods with a drawn service revolver, looking ‘like [something out of] a Wild West film’, to carry out his own reconnaissance on foot. Langton was furious and he became even more bitter that afternoon when he watched over to their left German fighters attacking the Polish drop near Driel without any Allied aircraft coming to their aid.

‘When I saw that “Island” my heart sank,’ said the Guards Armoured Division commander. ‘The Island’ was the name given to the flat, wet polderland of the Betuwe between the Waal and the Neder Rijn. ‘You can’t imagine anything more unsuitable for tanks.’ Adair was short of infantry when the task ahead was clearly ‘a job for infantry’, so he persuaded Horrocks to push the 43rd Infantry Division through instead. It faced a hard fight. With the Arnhem bridge now open, Harmel’s defence line was strengthened by the first part of Kampfgruppe Brinkmann, with Bataillon Knaust and a company of Mark V Panther tanks reaching Elst.

At first light that morning, the Household Cavalry Regiment sent two troops of D Squadron over the Waal to reconnoitre to the west. They came under heavy shelling and three White scout cars were damaged, but they managed to slip through Harmel’s defence line in the mist. They headed for Driel, where the Polish Parachute Brigade was due to drop.

Stranded in England by one delay after another, Major General Sosabowski and his men were living in a state of unbearable tension. They longed to get into battle in the Netherlands, and yet their thoughts were in Warsaw with the Home Army’s desperate defence. At 03.00 on 21 September, Lieutenant Colonel Stevens received a signal from First Allied Airborne Army confirming the new drop zone near Driel, and stating that the ferry was still in British hands. It also said that the bridge at Nijmegen had been taken, and British artillery would soon be within range to support the airborne division at Oosterbeek. Later in the morning, Brigadier General Floyd L. Parks, the chief of staff, First Allied Airborne Army, again assured Sosabowski that the ferry was in the hands of 1st Airborne Division. This was true at the time, but a German attack later that morning would push back the company of the Border Regiment guarding it and enable the Wehrmacht to destroy it.

At 07.00, the men of the Polish Parachute Brigade reached their three airfields. The fog lingered so thickly that the outlines of hangars, aircraft and buildings could scarcely be made out, but as it was warmer than on previous days, the Poles were determined to believe that this time they would take off. A young Polish officer described the scene: ‘A bustle of paratroopers can be seen around, before and behind the Dakotas, their equipment and personal kits carelessly scattered about on the cement runway. Some, in groups, are engaged in discussions, some take their time to rest, others visit their friends from neighbouring Dakotas. No one goes off too far, though, to be ready to load up at a moment’s notice. The men look for signs that might tell them that this time lift-off will not be cancelled. But it is delayed again, hour after hour.’

Soon after 14.00 hours, the mist had cleared just enough so the signal was given. Seventy-two aircraft took off from Saltby and Cottesmore, and another forty-six from Spanhoe. The larger group managed to find a window in the weather over the North Sea, but the troop carriers from Spanhoe were ordered to return, to the furious disbelief of their passengers. After they had landed and heard that the other group had carried on, their feelings of uselessness, ‘though it is not of our doing, throws us into despair, awakens feelings of helpless rage and a sort of envy towards our comrades on the ground’.

At 16.05 hours, a German signaller in the Dunkirk pocket reported a large number of Allied aircraft. Standartenführer Harzer ordered Oberstleutnant von Swoboda’s flak brigade to stand by in its new position south-west of the Arnhem road bridge. Sixty fighters on nearby airfields were ordered to take off. German accounts at this point became carried away with excitement. ‘The concentrated fire of the flak hit them like a burning fist,’ was just one exultant phrase. The Germans claimed that they had shot down forty-three Allied planes. One German eyewitness estimated a 60 per cent casualty rate among the paratroopers, but Polish accounts show such ideas to be wildly optimistic.

German flak was certainly heavy. Polish paratroopers, ardent Catholics for the most part, described the tracer arcing up towards them as ‘a rosary of sparks’. Five C-47 troop carriers were shot down and another sixteen damaged. German troops in about company strength were on or near the drop zone. ‘There was intense shooting aimed at the aircraft and also at the descending force of paratroopers,’ the brigade war diary stated.

Only a handful of men were shot as they came down. ‘Those who’ve been found by a bullet also land,’ ran one Pole’s romantic view of death in battle. ‘Their bodies float down under the white canopy slowly, majestically, as if they, too, were about to go into battle.’ Yet out of Sosabowski’s reduced force of 957 men, no more than four were killed and twenty-five wounded or injured. ‘Some close-quarter combat with knives and hand grenades followed. Enemy resistance was soon overcome and eleven prisoners taken.’ Their greatest anxiety was the inexplicable absence of the 1st Battalion and half the 3rd Battalion. They had no idea that they had been ordered back and feared that they had been shot down.

Their chaplain, Father Alfred Bednorz, saw the steeple of Driel church and went immediately to pay a visit on the local priest, presumably conversing in Latin. ‘I introduce myself as a Polish Army chaplain. The vicar is surprised, “How did a Polish priest get here?” I smile and point to the sky. He understands that the paratroopers who have just dropped here are Poles. We embrace each other like brothers. The vicar runs to his desk and hands me a lovely antique cross. “May this cross be a remembrance of our liberation from the Hitlerites.”’

Soon after landing, Sosabowski was greeted by Cora Baltussen, a member of the underground, who arrived on a bicycle. She warned him that the ferry had been destroyed and the Germans now held that stretch of the north bank. While setting up his command post in a farmhouse on the edge of Driel, Sosabowski sent off a reconnaissance patrol to the bank of the Neder Rijn to check on the ferry. But the patrol returned to confirm what Cora Baltussen had told him. The 1st Airborne across the river was under machine-gun and mortar fire, and the remains of the railway bridge were also in German hands. There was no sign of any boats.

At 22.30 that evening, Captain Ludwik Zwolański, the Polish liaison officer from Urquhart’s headquarters, appeared, still wet and muddy in his shirt and undershorts from having swum the river. He was known as the ‘black bandit’ because of his swarthy features. Not knowing the password, he cursed loud enough for a fellow officer to recognize his voice and clear him with the sentries. He pointed out Sosabowski’s command post and Zwolański entered and announced himself, saluting smartly. ‘Captain Zwolański reporting, sir.’

Sosabowski, who had been bent over a table studying the map, turned and stared at him in amazement. ‘What the hell are you doing here, Zwolański?’ he demanded. Zwolański explained that Urquhart had sent him to say that rafts would be provided to bring his men across the river that night. The fact that Zwolański himself had had to swim was hardly encouraging. Sosabowski nevertheless moved both battalions down towards the river. No rafts had appeared by 03.00 hours so Sosabowski brought the bulk of his men back to Driel to dig in. The riverbank would be far too exposed in daylight.

Zwolański had also brought an order from Urquhart that Sosabowski himself should cross the river at the first opportunity to report to 1st Airborne headquarters. Sosabowski had no intention of doing anything of the sort. He considered it madness for a commander to leave his troops in such a way, and when he later heard what had happened to the British, with the divisional commander, one brigadier and the commander of the recce squadron all separated from their men, he considered his decision even more justified.

While Browning wanted the Polish brigade to cross the river to reinforce the 1st Airborne Division and stave off disaster, Obergruppenführer Bittrich and Model’s headquarters believed that the new landings in the Betuwe south of the Neder Rijn were intended ‘to establish the link with advancing enemy forces coming north from Nijmegen’.

Bittrich’s defence line around Ressen was managing to block the road running north towards Elst and Arnhem. The 4th/7th Dragoon Guards had more luck to the west round Oosterhout. ‘British tanks moving in column’, the 1st Battalion of the 504th reported, ‘came to the area in front of the company about 17.30. They cleaned out German strongpoints, scared off a Mark IV tank coming out of Oosterhout, knocked out two tanks and a half-track on the road leading to Oosterhout, and wiped out a German mortar position. Bren gun carriers killed, wounded or drove out about 50 Germans in the orchard.’ This was the correctly chosen route if you were to pass the exam for the Netherlands Staff College. As it happened, that was the day the Dutch troops of the Princess Irene Brigade passed through Eindhoven and Nijmegen to an emotional welcome from their fellow citizens. They were lucky to get through, because the XXX Corps route was about to earn its nickname of Hell’s Highway.

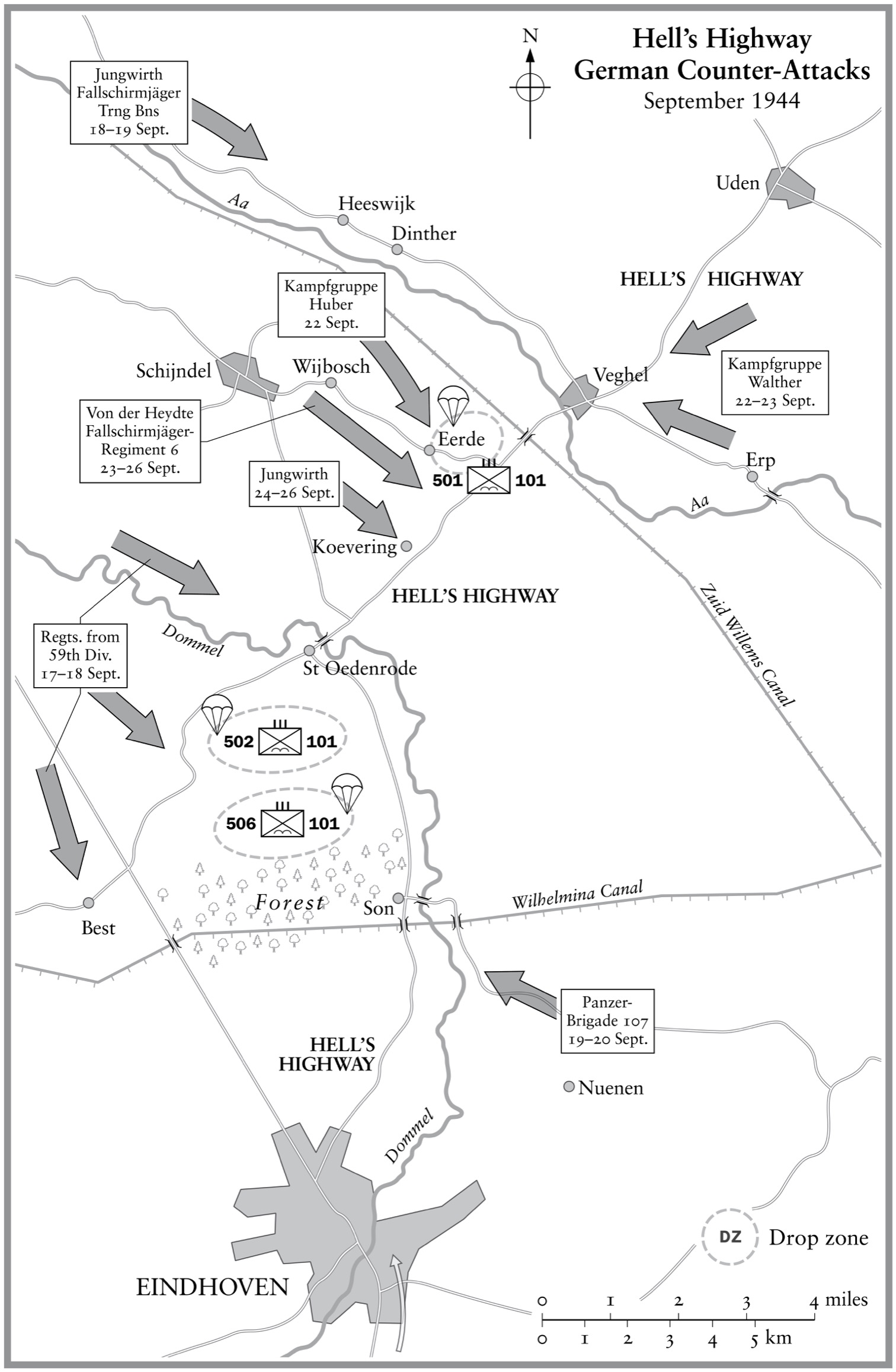

On 21 September, Colonel Johnson of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, building on Kinnard’s offensive strategy to defend Veghel, launched a regimental night attack towards Schijndel. Generaloberst Student went to see Generalleutnant Poppe in the school which he had made his command post at the southern edge of the town. Student asked how things were. Poppe replied drily: ‘The situation is somewhat spreckled.’ By that he meant that they were under attack in Schijndel and would have to get out, but the Americans were about to get a nasty shock when attacked from the east by the 107th Panzer-Brigade reinforced with paratroopers and an SS battalion under Oberst Walther.

Kinnard’s 1st Battalion was advancing when a 20mm gun mounted on a truck opened up on them. Kinnard saw his men throwing themselves into the ditches on either side of the road. The Germans were deliberately firing high with the 20mm using tracer, while at the same time another machine gun using ordinary ball ammunition was scything away at knee height. Not realizing that the Germans were up to their old tricks, Kinnard ran up the road, ordering his men to get up and push on. ‘Keep moving!’ he shouted. ‘That fire’s going way high.’ ‘Maybe it is, Colonel,’ a private answered him out of the darkness, ‘but we already have eight men hit in the legs.’ Others went forward in the ditches at a crouching run until they could engage the crew of the 20mm gun and force them to flee.

Entering Schijndel, they found that a number of the houses contained German soldiers fast asleep. By the early hours, the town had been secured. Kinnard was contacted by the local priest, who was also an organizer in the underground. ‘Keep your people off the streets,’ he begged him. ‘Tell them not to get out their bunting and to act as if we’re unwelcome. Get that word out to them tonight.’ There would probably be a counter-attack, and they might not be able to hold the town. The priest agreed and also promised to send off scouts on bicycles to see where German forces might be concentrating. The people of Schijndel fortunately did what they were asked and stayed inside their houses even after dawn had come. One paratrooper in the street was slightly startled when a shutter suddenly opened beside him, and a hand appeared offering him a cup of ersatz coffee.

The German tactic of perpetual attacks against the length of Hell’s Highway also affected St Oedenrode. Lieutenant Colonel Cassidy’s battalion prepared to counter-attack at 06.30 on 21 September, but supporting artillery fire in the preceding moments fell short, killing three and wounding another five of his men. The attack against the monastery which the Germans had occupied still went ahead. Each platoon had two British tanks in support. They faced heavy German fire, but it was very inaccurate, as if the enemy was firing without aiming at all. By the time Cassidy’s men had seized and searched the buildings, all the Germans had slipped away. But a sudden German artillery bombardment at around 10.00 hours hit the 502nd’s regimental command post, wounding Colonel Michaelis and most of his staff in a tree burst. Cassidy, walking back towards the command post, was blown into a ditch and lightly wounded. He had to take command of the regiment and decided to move the command post temporarily to the monastery, where it would enjoy slightly better protection.

The bitter fighting continued. ‘Mortar Sergeant James A. Colon was killed by a sniper. Pfc Robert L. Deckard was killed by a German shooting from near-by cover while Deckard was trying to help a wounded German. Lieutenant Larson, covered by the fire of several of his men, crawled up to the covert and dispatched the Germans with two grenades and a round from his .45. The 2nd Platoon leader, Lieutenant Wall, a squad sergeant and four others were badly wounded.’

Things improved only when a British tank, well over to the left flank and about 150 yards in front of the paratroopers, traversed its turret. ‘It fired on an 88 directly confronting the infantry and knocked it out. Then it scored a direct hit on a self-propelled gun near the 88.’ This ‘seemed to pop the cork out of the bottle’. Germans ‘began to spring up like mushrooms’ from the field in front, ready to surrender. ‘The officers were neatly groomed as if they had been planning a capitulation.’ One German soldier insisted that he had to retrieve his soap and toilet articles from his kitbag. ‘Someone booted his pants and he moved along.’ At 16.00 hours ‘a tank crossed the company front about 600 yards out. A six-pounder [anti-tank gun] which was attached gave it a round which hit just behind the tank and caused it to spin round with its tail toward C Company. A Sherman tank then poured three rounds into the Tiger and it exploded and went up in flames.’

Cassidy received orders to fall back on St Oedenrode, but that night the Germans reoccupied the monastery. Two days later it cost a British armoured regiment and an infantry battalion heavy losses to retake it. Horrocks’s Club Route was far too narrow to defend effectively, because of the delays to the two British formations flanking his XXX Corps. American parachute battalions and British armoured squadrons were having to dash up and down and back and forth like firefighters. General Taylor compared their role to that of US Cavalry troops defending railroad lines, outposts and settler trails from attacks by Native American tribes.

Constant interruptions, caused by German artillery shooting up convoys, meant that most American units were receiving only about a third of the K-rations they were due. The great German ration store at Oss discovered by the Household Cavalry Regiment was used to supplement diets. But because neither side could spare sufficient troops to secure the town, a strange situation developed. Each side sent armed parties to take supplies. ‘At this time what was apt to happen’, the Household Cavalry Regiment stated in its war diary, ‘was that the British drew rations in the morning – Germans in the afternoon. What a wonderful nation we are for standing in queues.’ A British officer observed that the German supplies from Oss were forcing his Guardsmen to admit that perhaps their ration packs of ‘compo’ were not the worst in the world after all. ‘German rations are not delectable,’ an American officer emphasized. With dry sausage made out of horsemeat and the rock-hard bread called Dauerbrot, American paratroopers found them even worse than the British compo variety, which they received from time to time. In compo packs, they liked only the treacle pudding. As for Player’s cigarettes, ‘they tasted like warm wind and were hard to draw.’ Another paratrooper said that smoking British cigarettes was ‘like sucking cotton through a straw’.

For Gavin’s 82nd Airborne, the attacks were coming not from both sides of the highway, but from the Reichswald still. Meindl’s II Fallschirmjäger Corps had taken Feldt’s Kampfgruppen under command because ‘his forces were not equal to meeting a serious, systematic attack and still less so to carrying out an attack themselves.’

Some of the most intense fighting was for a commanding feature, Den Heuvel, which predictably became known as Devil’s Hill. Kampfgruppe Becker from the 3rd Fallschirmjäger-Division attacked relentlessly. At one point Company A of the 508th ran out of machine-gun ammunition, with most riflemen down to five rounds each. An NCO who had been back to battalion headquarters appeared with four bandoliers just in time. They were also short of food. Constant attacks, especially at night, left the company exhausted. They tied empty canvas bandoliers together to run from foxhole to foxhole so that they could jerk each other awake whenever there was an enemy incursion. Company A managed to hold on until they were finally relieved on the night of 23 September.

The 3rd Battalion in Beek was hit by a sudden onslaught before dawn on 21 September. One company was virtually surrounded, but the others launched a fierce counter-attack and the young Fallschirmjäger were forced out of the town for good shortly before dusk.

Once darkness fell, the paratroopers of the 508th could see searchlights over to the left, probing the night sky from Nijmegen. Anti-aircraft batteries were firing away at German night bombers attempting to destroy the Waal bridge, which Generalfeldmarschall Model had so obstinately refused to demolish.