Take a Picture with “The Chief”

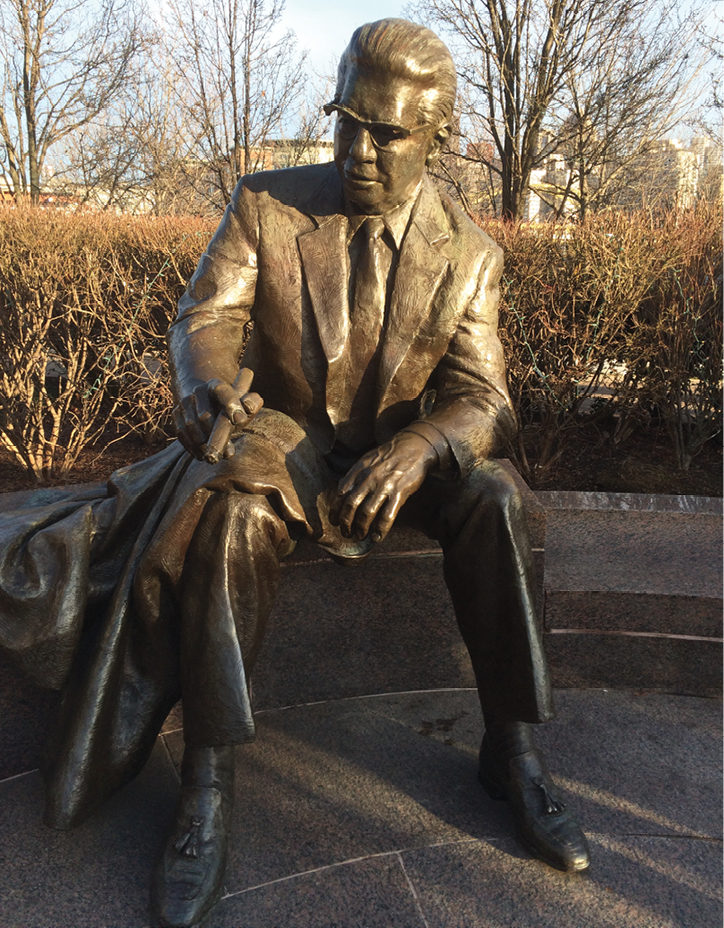

A resplendent life-sized statue of Art Rooney sits on a granite marble bench between Heinz Field and the Allegheny River, not far from where the ships that transport fans to games dock. It is a tranquil site on most days, the Steelers founder immortalized with slicked-back hair and glasses as well as a suit and a signature cigar.

Game days are a different story.

A steady stream of fans pose in front of the statue while pictures are snapped with cameras or cell phones, something that surely would have amused the man affectionately known as “The Chief.”

Rooney, who grew up on the North Shore, always prided himself on being a regular person despite his wealth and contributions to Pittsburgh.

The way in which he carried himself still stands out to former Steelers offensive tackle Tunch Ilkin, now the team’s color analyst for radio broadcasts, and Ilkin loves telling one story in particular about The Chief.

Ilkin and two other Steelers draft picks were sitting in the lobby of Three Rivers Stadium in the spring of 1982, waiting to talk to Chuck Noll. The three were in Pittsburgh to take physicals and meet with their new head coach when they had a chance encounter with Rooney.

The statue of Steelers founder Art Rooney outside of Heinz Field.

Rooney came bustling through the lobby wearing a cardigan sweater that was missing a button and chewing on one of his stogies. He started straightening up the lobby when he noticed the three players. He gave them a hearty greeting, not dropping even the smallest of hints of his stature, and asked them their names.

Ilkin went first and then one of the other players gave his name and asked Rooney if he was the janitor. Ilkin, who knew that Rooney owned the Steelers, was mortified.

The Chief? Not so much.

“I do a little bit of everything around here,” Rooney said with a smile.

Nothing better framed the man than his reaction to a question that might have insulted a lot of team owners.

“You could tell that The Chief was so honored that this young guy thought that he was a regular guy,” Ilkin said. “The Chief always used to say, ‘Don’t be a big shot.’ That was kind of his mantra.”

That mantra did not stop Arthur J. Rooney from becoming one, although with a common touch that made him a beloved figure in Pittsburgh. Actually, character is more like it since Rooney was one through and through, something that is so eloquently captured in the play The Chief.

The play, written by longtime Pittsburgh Post-Gazette sports columnist Gene Collier and Rob Zellers, debuted in 2003 and it transcends sports and the Steelers.

It’s set in Rooney’s office at Three Rivers Stadium and Pittsburgh native Tom Atkins is masterful as The Chief, spinning yarns while waiting to go to a banquet. Woven together through the one-man show, the tales tell not only the story of the Steelers but also the story of Pittsburgh.

The part that will leave Steelers fans with goosebumps comes near the end of the play. As The Chief explains how he missed the greatest play in NFL history, the “Immaculate Reception” is replayed on a screen that has been lowered in the theater and the audience starts cheering.

The second time I saw The Chief—and yes, it is worth seeing at least twice—many in the audience were ready for that scene. That is how I witnessed the surreal sight of people waving Terrible Towels inside of O’Reilly Theater in Pittsburgh’s arts district.

The Chief has played at other venues with different actors who were carefully screened before getting permission to tackle the role of Rooney. All you need to know about the authenticity of the play is that Joe Greene was moved to tears after watching it during training camp one year at St. Vincent College.

The life of Rooney lends itself to the stage because of how colorful he was and the unlikely story of how he bought the Steelers.

Rooney had been a terrific athlete while growing up on Pittsburgh’s North Shore and he excelled in boxing and baseball. He bought into the NFL in 1933 and sustained the Pirates (later to be renamed Steelers) through winnings from the track. Rooney, who was given his nickname by one of his sons, guided the franchise through World War II and tough financial times but never saw it win consistently for four decades.

That changed in the 1970s, but Rooney’s unassuming ways did not. That explains a scene in the victorious locker room after the Steelers had suffocated the Minnesota Vikings’ offense in Super Bowl IX.

The Vikings had made the mistake of trying to run at Greene in that game and managed just two field goals in a 16–6 loss. Greene intercepted a pass, forced a fumble, and helped limit the Vikings to 17 yards rushing. Linebacker Andy Russell, the Steelers’ defensive captain, was getting ready to present the game ball to Greene when he spied Rooney among the crowd in the back of the room as if he was just anybody else.

Russell started yelling and beckoning for Rooney to join the players on the stage. When The Chief finally made it there Russell handed him the game ball.

“He just seemed so happy,” Russell recalled.

Players were just as happy to deliver that moment to Rooney.

“He was just so gung ho about his team,” Russell said, “and he’d come into the locker room and walk around and pat people on the back, especially if they were hurt.”

The office immortalized in The Chief is no longer around as Three Rivers Stadium was demolished in 2001. But Art Rooney retains a larger-than-life presence at the confluence of the three rivers where the Steelers still play.