In 1960, the Central African Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland found itself approaching a crossroads. Harold Macmillan’s ‘winds of change’ speech sounded the alarm bell for all white central Africans. Britain was ‘closing shop’ in Africa. Her interests were being re-directed ‘towards Europe and away from Empire and, reluctant to have to fight wars of liberation with impatient nationalists, MacMillan appointed Iain MacLeod, Colonial Secretary to liquidate the Empire as quickly as possible.’1 White Rhodesians were already witnessing the tragic and catastrophic results of Belgium’s irresponsible and virtual overnight ditching of her huge colony of the Congo, the repercussions of which persist to this day.

Reacting to their electorate’s representations and noting the increasing disturbances being caused by the subversive activities of the nationalists in Nyasaland (Hastings Banda) and Northern Rhodesia (Kenneth Kaunda), the Federal government decided that additional security was required. The Federal GOC, General Long, had four regular African battalions under his command, namely the Northern Rhodesia Regiment, Nyasaland’s two battalions of the King’s African Rifles and Southern Rhodesia’s 1st Battalion, The Rhodesian African Rifles. To counter-balance these, he was ordered to raise a new, regular, all-white battalion to be based in Southern Rhodesia. In addition an armoured car regiment (Ferrets)2 and a paratroop (SAS) squadron were to be formed. General Long appointed Rhodesian-born Lieutenant-Colonel John Salt,3 then commanding 1RAR, to command the new battalion.

Recruiting campaigns began locally, in South Africa and in the United Kingdom. As soon as recruits were attested, they were sent to No. 1 Training Unit at Brady Barracks in Bulawayo.

Paul Wellburn, an early recruit, recalls: … At the doddering age of twenty, my life was slipping away. ‘Make the Army your career’ the ad said … Sitting next to the swimming pool at KGVI Barracks a few weeks later, as the first batch was made up, we ogled Captain Mick Horne’s daughters and thought, “This is the life.” I vaguely remember names like Davidson, Baxter and Heppenstall, but after a short while, about thirty of us had been assembled, kitted out, TaB’d (inoculated) and loaded onto the Bulawayo train—the dining-car was well used that night. Two smart WO2s, complete with red sashes, met us at the Bulawayo station next morning—how nice. These two gentlemen (Percy Johnson and Bert Brookes) gently herded us aboard a couple of trucks and conveyed us to Brady Barracks where the proverbial shit hit the fan …

Major Bill Godwin was commandant at Brady. Together with captains Peter Miller and Peter Nicholas and a handful of NCOs, he drew up a training programme. This consisted of two and a half hours of foot drill every morning conducted on the airstrip some distance away (Brady had been an RAF wartime air station). Afternoons were devoted to lectures. At this stage, and indeed for some five years or so, the unit was equipped with SLRs (Self-Loading Rifles)—a British modification of the Belgian FN. The FN in fact finally became the unit’s standard infantry weapon.

It needs to be said here that Brady Barracks appears to have been thoroughly detested by every recruit who signed up to join the as yet unnamed regiment. Accommodation was of a very poor standard. At Brady, everything appeared, in modern parlance, to have been recycled—no two beds were alike. Food was also indifferent and got so bad that one lunchtime everyone refused to eat the meal provided. All this had a demoralizing effect on the young recruits. In an already established unit, the old sweats would have had a steadying effect. However, at Brady, this influence was absent. As a result, there were frequent desertions, facilitated by the fact that the camp was not fully fenced, which enabled any disgruntled recruit simply to walk out after dark.

When Salt arrived, Godwin was appointed 2IC and Sergeant-Major Ron Reid-Daly was appointed RSM. The new unit officially came into being as the 1st Battalion The Rhodesian Light Infantry on 1 February 1961. For the next nineteen years (until the laying-up of the colours on 17 October 1980) the battalion was to earn for itself an enviable reputation as one of the world’s foremost anti-terrorist forces.

RSM Reid-Daly and his fellow NCOs had their work cut out. They had hundreds of scruffy individuals to transform into soldiers. By the very nature of things, some of them were going to be unsuitable. However, looking them over, the training staff was not discouraged. Somewhere under the layer of civilian clothing and slovenly attitudes were the makings of soldiers. “Nothing wrong with these blokes that a good kick up the jack won’t put right,” would have been Reid-Daly’s private assessment.

Wellburn continues: … We were a varied, rough and colourful bunch of skates from Rhodesia and Joeys [Johannesburg], ducktails and Poms from Cockneyland and Jocks from Glasgow. Having grown up in Bulawayo, I could gauge the public’s reaction. It was generally one of caution bordering on terror. Mickey Most, a pop star of the time, gave a concert in the City Hall. A No. 1 Training Unit member, who shall remain anonymous, disliked one of his songs and pulled him off the stage by his microphone lead …

Though the majority of the recruits were from South Africa, there were significant numbers of men from Rhodesia and Britain. Inevitably, friction would and did occur. Scraps, when they happened, would be sparked off around the washing-up trough outside the troops’ dining room (‘the graze hall’ in RLI parlance) as the men jostled each other when rinsing out their eating utensils. Major differences and pecking orders were sorted out in the normal way—after hours in the barrack room or behind the block.

A few more instructors began to arrive from the UK, notably from the Coldstream Guards and the Royal Highland Fusiliers. As the recruits completed their basic training, they were posted to companies A, B, C or D. The senior company was B and D was composed of boy soldiers, the youngest being sixteen and a half years old.

However, desertions continued, reaching a peak in April 1961 when 29 individuals went AWOL (absent without leave). The reason for this was to be found in a nearby Bulawayo hotel where agents of President Moise Tshombe’s secessionist Katanga government were openly recruiting mercenaries. What they offered was irresistible to some—£300 per month paid into a Swiss bank account, all on-service costs and expenses together with ample opportunities for looting captured enemy property. What the agents got in return, if an RLI man signed up, was a freshly and fully trained soldier in peak fighting condition. Some recruits, however, deserted simply because conditions were not to their liking or they were homesick.

No. 1 Training Unit Bren gunners on excercise at Brady Barracks, Bulawayo. This photo was used as an early recruitment poster.

A Company Command Post at Solwezi on the Congo border, 1961. At left, Major ‘Digger’ Essex-Clark and his 2IC Dave Parker.

The unit’s Regimental Police were hard-pressed to pursue and locate absconders. At one stage Provost Sergeant Ernie Thornton, ex-British SAS, took his team to Beitbridge, the border post between Rhodesia and South Africa, with the intention of waylaying any deserters intending to cross into South Africa. After some time in the appalling heat, Thornton decided to go for a quick drink, leaving one of his policemen on OP (observation post) duty. When he returned, he was mortified to discover that the policeman had also deserted.

Despite these tribulations, a battalion was taking shape. Discipline was strict and the constant emphasis on ‘spit and polish’ was having an effect. The awakening of a sense of pride in their training and confidence in themselves was becoming apparent. Inter-company rivalry materialized and a battalion regimental march was born, though rather by accident than design. Lance-Corporal Mac Martin, an erstwhile member of a famous Scottish regiment, was a skilled piper. When the unit went out on route marches, he would strike up lively marching tunes. When the saints go marching in quickly became a firm favourite among the men to the extent that when it was not played at one of the unit’s earliest appearances, a retreat ceremony in Bulawayo, the men sent a representative to the RSM.

“Sir, the men are flat [upset] that our regimental march was not played as we marched off,” complained the spokesman.

Reid-Daly replied tersely to the effect that he was not aware that the unit had a regimental march.

“Oh, yes sir!” the representative replied keenly. Then taking his life in his hands he proceeded to name the tune. Taken aback at the man’s effrontery and appalled by the unimaginative choice, Reid-Daly approached Salt who surprised him further with, “I rather like The Saints.” The RSM gave up. It looked as if his battalion was stuck with an American ditty.

A further regimental appendage was gained when General Long and Colonel Salt arranged for the battalion to be presented with a regimental mascot in the shape of a cheetah. Why such an unlikely animal was chosen has never been explained. (The cheetahs were never a success. The first pair died mysteriously on 6 October 1963 and were buried with full military honours. Over the next few years their successors went the same way. Although further cheetahs did not materialize for some time, the animal was always kept on the unit’s roll as its official mascot.)

An outbreak of foot and mouth disease in Matabeleland occasioned the battalion’s first operational duty. They were to relieve 1RAR, which was manning a cordon around Gwanda. C Company, under Captain John Wells-West was pulled out of the cordon to an alert of possible trouble in Fort Victoria’s black township, where Corporal Mike Curtin had spotted a rifle-toting man approaching the township—the cause of the alarm. The weapon turned out to be an air rifle.

In June 1961, Second Lieutenant Brian Barrett-Hamilton, with a 13-man section, was flown to Aden on attachment to the British Army, which was responding to Iraq’s threat to take over Kuwait’s oilfields—Britain’s main source of oil. From Aden, the men went to Bahrain where they remained on stand-by for two months. Barrett-Hamilton’s platoon was tasked as infantry support to the British Centurion tanks. Nothing dramatic occurred and the Rhodesians returned home, leaving Iraq to postpone its invasion of Kuwait for another 30 years.

In this year the battalion established the first of its famous long marches. Six teams of four men each took part in an attempt on the 80-mile endurance march from Gwanda to Bulawayo—with the final 20 miles being treated as a race. Only six men completed the event—D Company’s Lance-Corporal Joe Walsh was the winner.

The Congo

The problems in the Congo began to escalate. The secessionist Katanga province bordered Northern Rhodesia and troops were needed to man the border in case the troubles spilled over into the Federal territory.

The battalion spent July and August rehearsing mobilization procedures, which required kit to be issued and loaded onto vehicles, and trial runs made to the airport and back—over and over. Some men got so blasé about the constant packing and unpacking routine of ‘Stand by’, followed by the deflating ‘Stand down’, they began filling their kitbags with newspaper rather than the heavy standard kit. When the Congo call-out did eventually materialize on 9 September, these careless individuals found themselves spending three months on the border with no kit other than that which they could scrounge from their comrades.

The battalion entrained for Salisbury where they boarded Canadairs of the Royal Rhodesian Air Force at New Sarum. From here they were flown to Ndola in Northern Rhodesia. The boy soldiers of Major ‘Mac’ Willar’s D Company had originally been left out of the operation as it was felt that they were still too young to be involved. Willar wasn’t having any of it. He pointed out to the brigadier that his company not only had more marksmen than any other, they had also thrashed the other companies at many events. They were allowed to go.

The battalion arrived at Ndola where the men stayed overnight. C Company then moved on to Bancroft, a small mining village off the main road. They parked their vehicles along one of the main streets and were soon being plied with refreshments from the welcoming community. The other companies based up at Chingola, Kitwe and Mufulira, where the men received similar welcomes.

The troops, waiting in half-expectation of action, found themselves instead dealing with floods of refugees pouring over the border on a sauve-qui-peut basis, all bearing distressing tales of massacres and near-escapes. They presented a pitiful sight. Most had nothing except the clothes on their backs. Traumatized and shocked, they had lost everything. In their dealings with these refugees, the troops, understandably, were as gentle as possible as they conducted the refugees to the reception centres.

From across the border rumours were rife. One thing that the Rhodesians were sure of was the fact that the United Nations troops would prove both incapable and unwilling to deal with the prevailing chaos. The Rhodesians were totally unimpressed with the sloppy and unsoldierly Swedish troops who represented the United Nations. When the Katangese refused to supply the UN troops with beer, the Swedes sent an urgent order to Northern Rhodesia Breweries in Ndola for 12 tons of canned beer. C Company heard of this and stationed itself at the point on the border where delivery was to take place. The troops duly arrived in their white UN-stencilled Mercedes trucks to collect their order. The Rhodesians decided that it was their duty to ensure that the order was correct before it was handed over. They then proceeded to open, and savour, can after can before the very eyes of the frustrated Swedes who could do no more than glare helplessly. It so happened, however, that when the top layer of cans had been broached, the lower layers were found to contain half-full or even empty cans. It appeared that the Breweries had not anticipated this impromptu ‘quality control’ by the RLI while the product was still on Federal soil. The crestfallen Swedes drove off into the sunset, trucks loaded with rattling half-cans of beer.

At Chingola, some weeks later, Frank Turner and his company were guarding a wooden bridge, his men searching all vehicles passing through the checkpoint. A Cadillac suddenly pulled up and a uniformed Katangese jumped out of the front seat and opened the rear door. From the vehicle emerged a man that Turner and everyone else immediately recognized. The man was big-boned and his sad eyes seemed to reflect the entire tragedy of Africa. He smiled at the Rhodesians and said, “There is beer and cigarettes inside. Help yourselves.” The search revealed more than beer and cigarettes. The boot was full of suitcases, all of which were packed tight with cash. After the search, the man shook hands with the RLI officer, got into the car and was driven away. Moise Tshombe had fled Katanga.

With the Katanga trouble over, the RLI returned to Brady Barracks. Here the men were utterly dismayed to discover that in their absence their barracks had been plundered. Over 80 percent of the battalion lost all their civilian clothes and belongings. Some cars had also been stolen. How this came about, no one could explain. On top of this, the battalion was being transferred to its new and permanent home in Salisbury where construction of the barracks at Cranborne was nearing completion.

It is true to say that through the rowdiness of a few individuals, a poor reputation had been gained by the battalion in Bulawayo. The townspeople were relieved to witness the battalion’s farewell parade which proceeded down Main Street in shambolic fashion because of the unevenness of the streets. Reid-Daly was less than impressed with the performance and gave the men a severe dressing-down.

A Company notes

This is an essay of very personal recollections and observations by a once-upon-a-time commander of A Company, 1st Battalion The Rhodesian Light Infantry—from November 1960 to December 1962—written by Brigadier John ‘Digger’ Essex-Clark, DSM (Retd.) (Rhodesian Army, 1951–1963; Australian Army, 1964–1985):

… This somewhat disjointed monograph records my most significant memories, personal observations and comments about my professionally fulfilling and heartening period of command of A Company of the No. 1 Training Group and then 1st Battalion of The Rhodesian Light Infantry from late October 1960 to December 1962. I had the privilege and responsibility of being with and then commanding the company for only 26 months. During my period with the battalion, I knew very little of what was happening in the rest of the battalion, particularly in the second half of 1961 when we were fragmented and deployed very separately on Congo border operations in Northern Rhodesia. They were heady days indeed. These events happened over 44 years ago and, as we all know, memories fade and can become distorted. Now well retired and feeling like a war-horse out to pasture, I find that names of old friends and contemporaries with whom I served in different units and different armies at different times in different places, and whose character and style are firmly imprinted in my mind, are often hard to remember distinctly in their correct organization, event and place. These events also happened long before the RLI was heavily involved in the long ‘Bush War’ of the ’70s, and therefore does not have the tense excitement and constant danger of those days when your enemy was relatively obvious and had to be tackled immediately.

I was posted in October 1960 from an irrelevant staff job doing nugatory work at Army Headquarters in Salisbury to become 2IC of A Company No. 1 Training Unit. The unit (battalion sized and organized) had been formed as the only European or totally ‘white’ unit in the Army of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (‘the Federation’). Major ‘Dusty’ Miller was A Company’s initial commander. We were in Brady Barracks, the old ‘RAF Kumalo’ base, with the lugubrious, pipe-smoking, Lieutenant-Colonel John Salt as our commanding officer and the combat-experienced Major Bill Godwin as our Battalion 2IC. Majors Dudley Coventry, Tony Coppinger, Mac Willar, and Mike Roach had B, C, D and Headquarters Company, respectively. I was the youngest, the most junior, and the only one without experience in another army. Captain John Thompson was our adjutant, and our regimental sergeant-major (RSM) was the ebullient and pugnacious Warrant Officer Ron Reid-Daly.

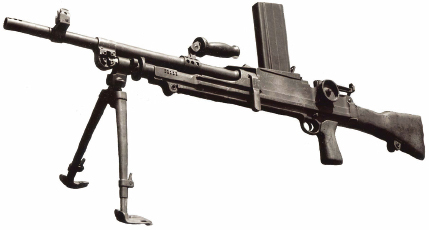

Our task, with a motley group of warrant officer (WO) and non-commissioned officer (NCO) instructors, was to give basic training to recruits as they came in from the two Rhodesias, South Africa, the United Kingdom and elsewhere. If I remember correctly, our instruction was concentrated on drill, the rifle and bayonet, the Bren light machine gun, grenades, basic fieldcraft, very simple navigation (map-reading and compass), plus dress and barracks discipline. Our instruction was based on the well-tested system developed by the British Army from whence many Rhodesian Army instructors had learnt their infantry instructional skills and techniques. Fortunately, some of our recruits had had some previous military experience with their national armies. The others had to start from scratch.

The Training Unit had no time for anything but creating an infantry battalion organization, without any team or tactical training as rifle sections, platoons or companies. In fact, the nearest my A Company had got to any field training was when our platoons or the company went onto the rifle ranges to shoot their rifles and LMGs, and throw grenades. Blending men of different military and national cultures, or with no training at all was interesting and at times, somewhat tricky. It felt as though we ourselves were almost a mercenary group within a very regular army. We of course attracted some bad eggs; some being the usual riff-raff of society and soldiers of adventure and we had rid ourselves of these poorly self-disciplined men as soon as possible. Nevertheless, we had some superb men and found many of our junior NCOs and sergeants from within our recruits. We also had two attachments from the British Army, the solidly built Captain John Taylor, our Regimental Medical Officer (RMO) and in A Company we had the experienced, morale-building and invaluable Sergeant Evans. Many of our officers had risen through the ranks in the Rhodesian Army, and/or had had previous service in the British Army, including some subalterns and junior captains who had been trained at Sandhurst in the United Kingdom. Only our CO had long ago transferred from the British South Africa Police (BSAP)—Southern Rhodesia’s police force.

In essence, our officers, warrant officers and many non-commissioned officers were deeply cultured in a British Army system and organization. Our men were more culturally mixed and about half of my men were South Africans or descended from Afrikaner stock; the rest were a mixture of British expatriates or Rhodesian-born.

I had joined the Southern Rhodesian Staff Corps as a private. I was commissioned second lieutenant from the rank of sergeant, into the Staff Corps and posted to The 1st Battalion Rhodesian African Rifles and served with them as a rifle platoon commander in Malaya (1956–1958).

We formed the battalion while the Federation was in a relatively peaceful and ‘non-emergency’ situation, though there were already some deep subversive rumblings in the Federation, and we would not have been formed as a ‘white’ battalion if there had not been. I was not naïve about this, having been sent by Sir Humphrey Gibbs (the then Governor of Southern Rhodesia) to the Kutama Mission in the Zwimba Reserve to put a Mr. Robert Mugabe under house arrest; so I had listened to Mugabe’s chillingly realistic prophecies and intentions, ‘from the horse’s mouth’, just before I had been posted to 1 Training Unit. I thought Mugabe was a charismatic, highly intelligent and very dangerous man. I felt that an anaemic ‘house arrest’ would only make him more dangerous.

During our basic training at Brady Barracks, we also found the time to develop our rugby XV and compete as the ‘Rhodesian Light Infantry’ in the Matabeleland rugby competition. We had some remarkable games in the province, including some splendid games at Hartsfield in Bulawayo. We probably lost more than we won, but we established a battalion identity and the proud support of the men by doing so. Poignant memories are of playing against my old team, Bulawayo Athletic Club (for which I’d played when 1RAR was at Heany, now Llewellin Barracks, and was training for Malaya). Also, I remember, with apologies, when once playing tight-head flanker, I pushed too hard and cracked one of the ribs of young Lieutenant Alistair Boyd-Sutherland who was playing as tight-head prop. Our stars were Corporals Young and Meecham, Lieutenants Brian Robinson and Jimmy Smith-Belton, the tough Sergeant van Zyl, Captain Tom Davidson; and our RSM, Ron Reid-Daly. Other stalwarts were Corporals Treloar, Liebenberg and Danie van Eeden, our big lock and enforcer, and youngsters such as Privates Lloyd-Evans, Douglas, Gillespie, Higgins and Lotter.

While writing on sport, one of my fondest and most unusual moments is of me sweating it out with Dudley Coventry on the squash court at Brady Barracks. Bill Godwin (my mentor as a subaltern in 1RAR) had leaned over from the gallery railing and told me that I had been promoted to acting major, and to take over A Company from ‘Dusty’ Miller who was posted to take command of the new reconnaissance squadron, the Selous Scouts (not be confused with the later regiment formed by Reid-Daly).

While we continued basic training a superb moment was on 1 February 1961 when we became the ‘Rhodesian Light Infantry’; even so, we still had a few of our better-performing recruits being siphoned off to the newly reformed C (Rhodesia) Squadron SAS and the other newly formed Selous Scouts.

My first company ‘call-out’ and deployment was to settle a minor internal security problem in Gatooma that only took our swift and positive presence for matters to settle. However, we only really had a barrack-room organization and barrack-room cohesion as far as team-work and group morale was concerned. We had not yet trained to fight.

Seven months after we had started our basic training and our recruits were settling into the battalion, and before any effective collective or group tactical training could take place, the Congo erupted. The republic had been given its independence by Belgium through the pressure, auspices and protection of the United Nations (UN). Colonies of any nation had become unpopular in the new world.

Katanga Province, a state of the new Republic of the Congo (under Moise Tshombe), with the covert support of the Belgian industrial giant Union Minière, seceded from the republic. Without the economic benefits of the Katangese copper mines, the Congo was an economic basket case. The republic’s pathologically unstable and communist-oriented Prime Minister, Patrice Lumumba, was arrested by the Congo’s President Kasavubu and mysteriously disappeared. The Congo became a shambles. General Mobutu, previously a medical corps corporal, became the commander of the Congolese National Army (CNA). The Congo became a débâcle with civil war rampant and the Congolese National Army mutinying. As a result, the United Nations had the stabilizing Belgian troops removed and dispatched a polyglot force from nations such as Ethiopia, Eire, India, Nigeria, and Canada (to provide radio communications), to settle the turmoil. The Warsaw Pact together with the Asian and African blocs, not to mention India, who recognized the political, strategic and economic advantages for themselves in the Congo, had helped sway this decision. The Indian Army provided the UN force commander and the commander of the element in the Katanga Province.

Dave Parker and ‘Digger’ Essex-Clark prepare their dinner. Solwezi, Congo border.

The A Company flag as sketched by ‘Digger’ Essex-Clark.

The Federation was not popular in the UN, or among some politicians in the United Kingdom. There was a political hiatus and misunderstanding between the UK and the Federal government, and little trust between the UN and the Federation. With the Congo situation raging out of control on its borders and the production of copper for export under threat, the Federation, against the wishes of the UK and the UN dispatched the Rhodesian Light Infantry and other Federal forces to Northern Rhodesia. They were tasked to protect the border against foreign incursions or crossing of the border by any forces involved in the unrest, including those provided by the UN. Covertly, yet strategically, the Federal government supported the Katangese secession, much to the chagrin of the UN and the UK government. The situation was tense. The task of the Federal armed forces was to prevent any foreign movement and deployment of any force bypassing the Congo through far-northwest and central Northern Rhodesia. It sounded simple, but was confused by international politics and ‘point-scoring’ by a bevy of nations, slippery politicians and rubbery international relationships. There was also the challenge of handling the many refugees fleeing the dangerous shambles in the Congo Republic.

Federal Army tactical doctrine at that time was very loose but based on a developing Internal Security Operations précis that concentrated primarily on aid to the civil power and the principle of ‘minimum force’. There was also some material on ‘local limited war’ that was not yet doctrine. Tactical training was very much the province of the School of infantry at Gwelo and based on the British Army doctrine and pamphlets of the time. We in the RLI had no effective tactical doctrine or collective tactical training for what we were about to face. Nor did we have Standard Operating Procedures (SOPs) for any form of aggressive reaction to a hostile force.

We flew by an Air Force Canadair transport aircraft into the large Copperbelt town of Ndola, and collected some clapped-out Public Works Department (PWD) trucks to take my company to the showgrounds at Kitwe. My headquarters and 1 Platoon stayed there and 3 Platoon was deployed to the Kipushi border crossing. 2 Platoon deployed nearby to the Bancroft Mine area. Fortunately our own vehicles from Bulawayo soon replaced our locally obtained and unreliable PWD transport.

As my second-in-command, I was fortunate to have Captain David Parker, a crackerjack Sandhurst graduate, whom I had previously got to know well in the Rhodesian African Rifles. He was a good leader and steeped in British Army conventional warfare doctrine and tactics. The British parachute-battalion-experienced Warrant Officer ‘Crash’ Hannaway was my company sergeant-major (CSM) and I had experienced sergeants in my three platoons, one of whom, Sergeant Lourens, commanded the officer-less 1 Platoon. I had only two officer platoon commanders, both young, but well trained and keen. They were the super-confident and sharp-witted Lieutenant Brian Barrett-Hamilton from Sandhurst with 2 Platoon; and the phlegmatic, steady and deliberate Lieutenant Bob Davie with 3 Platoon.

While in Kitwe in the Copperbelt area, we sorted out immediate problems in vulnerable and sensitive spots such as Tshinsenda, Konkola and Kasumbalesa. As the battalion and others arrived we were then redeployed from the Kitwe area to Solwezi in the centre–north of western Northern Rhodesia in an attempt to cover the over 500-kilometre-long border from Kipushi, adjacent to Katanga Province, to Mwinilunga near the Angola/Congo border junction almost to the easternmost portion of the Caprivi Strip. My company’s task now was to prevent any foreign movement and deployment of any force bypassing the Congo through that area. There were two principal access roads into our area of responsibility—one at Kipushi and the other the road from Kolwezi, a Congo centre of activity, well north of the border. I also had to protect the Mwinilunga approach. I deployed Lieutenant Brian Barrett-Hamilton’s 2 Platoon to Mwinilunga, and Lieutenant Bob Davie’s 3 Platoon remained near Kipushi. The mining township of Kipushi was on the border. Both those platoons also protected any fragile customs posts at those locations. There was in fact no customs post at Mwinilunga, only a lonely district commissioner and his ‘messengers’. The lonely Lunda customs officer at Kipushi could speak the local dialect and English. He could also speak French far better than my appalling schoolboy patois and, at times, became a valuable interpreter.

At Solwezi I set up my headquarters and 1 Platoon (Sergeant Lourens in command, but under the wing and the watchful eye of Captain David Parker). They became my ‘centre of gravity’ and my reserve.

At Solwezi our reception from the district commissioner and his staff was extremely ‘colonial British’, polite but very cool and not very helpful. I had to remember that Northern Rhodesia was still a Crown protectorate and only ‘federated’ with Southern Rhodesia and the other Crown protectorate, Nyasaland; Southern Rhodesia was a self-governing and semi-independent Crown colony. There was no single or homogenous civil service in the Federation. It felt as though we were distrusted aliens to the Northern Rhodesians and their British district commissioners. The Federation was not a cohesive nation. There was still the restraining legacy of British colonial power and their condescending manner in Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland. It seemed to me that, to many of them, Southern Rhodesia was an irritating, unpredictable and overbearing upstart that was interfering with their comfortable and unruffled lives.

Nevertheless, the Solwezi district commissioner enabled us to use the nearby abandoned and subsidence-prone mine township and mine offices at the old Kanshansi mine for live-firing, close-quarter battle drills and minor section-level tactics, such as street-clearing, house-to-house combat and rat-holing through buildings. For this, Sergeant-Major ‘Crash’ Hannaway’s parachute-battalion experience was invaluable.

This was the only tactical and team training that my company had had so far; apart from practising some vehicle counter-road-ambush drills on our road journeys. We continued constant and intensive patrolling and ambushing at section and half-section level at every opportunity. My raw recruits were quickly learning ‘on the job’. We had been given no ‘rules of engagement’ as is done in these days of political correctness, internationally accepted yet hypocritical opprobrium for military weapons and combat, and resulting legal constraints. Common sense, pragmatism and the security and safety of my own troops was my single modus operandi. Foreign aggression from any source would be dealt with quickly, clinically and harshly. We soon found that swift, positive and aggressive action would shrug off any minor trouble that faced us.

We had little ‘intelligence’ about what was happening in the Congo. Most of our information came from listening to the news from the civilian radio stations and what we encountered in front of us. I possessed only a locally purchased commercial tourist road map (Atlantic Petroleum Company) to make tactical decisions, plus my battered but invaluable Union Castle Line Year Book and Guide to Southern Africa—1947, which contained some good large-scale maps and area information. We did not even have the city newspapers that were keeping the rest of the Federation informed about what was going on. My wife probably knew more about the Congo trouble than I did.

After a quick reconnaissance, I saw that the roads passing through the customs posts on the border-crossing roads at Kipushi and north of Solwezi to Kolwezi could be easily bypassed by vehicles using a variety of bush tracks, as could be done almost anywhere along the virtually unmarked border. At Mwinilunga, Brian Barrett-Hamilton later told me that there were no tracks that could take anything but a four-wheel-drive, and then with great difficulty, though I did not know this at that time. It was obvious, however, that the area of greatest tactical importance to my task—to prevent any foreign military road moves from within the Congo to deploy forces through Northern Rhodesia from east to west or vice versa—was the single road bridge over the Kafue River, a few kilometres west of Kipushi. To his delight, I said a polite goodbye to the district commissioner at Solwezi and deployed my headquarters, with 1 Platoon (initially David Parker, Corporal Chaney and a radio to maintain liaison with the district commissioner and to control my logistics) to that bridge. I left 2 Platoon with Brian Barrett-Hamilton in command at Mwinilunga, and the experienced Sergeant Paddy Driver as his platoon sergeant. Driver later left the RLI and joined the US Army. (I met him serving as a master sergeant with a US Infantry battalion in Vietnam in 1966); 3 Platoon was now commanded by Bob Davie at Kipushi, with Daly as his strong platoon sergeant.

1 Platoon was my reserve and, with it and my headquarters, we dug a tactical defensive position at the bridge with concentration on the road approaches from the west and northeast. Bob Davie would be able to warn us of any threat approaching from our northeast. Brain Barrett-Hamilton far to our west, and Solwezi to our near-west could be easily bypassed, so we positioned a half-section standing patrol on the road a kilometre to our west with radio and Verey pistols with signal flares for early warning should any group of foreign vehicles approach along that axis. Each separate group of my company now had sufficient transport to move independently in an emergency and we, at our defensive position at the bridge, could accommodate the complete company if necessary. We also had sufficient transport to reinforce Bob Davie’s 3 Platoon at Kipushi. However, time and distance meant that Brian Barrett-Hamilton’s 2 Platoon was on its own, but I had every confidence that the capable and quick-witted young Barrett-Hamilton could easily handle the sort of problems that he would encounter at or near Mwinilunga. I found out years later that 3 Platoon had had a very laid-back period at Mwinilunga, having cut a track to a standing patrol north of Mwinilunga near a river that also provided a ‘fine’ swimming pool. No one from the Congo was silly enough to use that thick-bushed and trackless route through Northern Rhodesia and so 3 Platoon had no further excitement.

By regularly driving back in my Land Rover, I retained constant personal contact and liaison with the district commissioner at Solwezi because he had the only telephone from which I could quickly contact the headquarters of 1RLI, which was well to the south. We needed this communication because our WS62 radios sets were not always reliable. We could also refuel our vehicles at Solwezi. Once I started regularly driving back to Solwezi, David Parker returned to the headquarters to keep a fatherly eye on 1 Platoon at the Kafue Bridge.

The district commissioner, though still very wary of us, was in friendly contact with Chief Mwata Amvu of the local Lunda tribe whose people were spread over Northern Rhodesia and the Copperbelt, the southern Congo and into eastern Angola. His daughter was married to Moise Tshombe. Therefore we needed the chief’s friendship and support. I met with the chief and his huge, colourful entourage and we agreed that we would not interfere with any of his tribe and he would provide us with as much information as he could about the movements and activity of the UN troops, the mercenary forces and the Congolese National Army (CNA). Driving along that road back to Solwezi to use the phone or effect liaison with the district commissioner about local matters occasionally led to a few minor incidents with wandering CNA, UN Ethiopians, and other brigands, but we brushed them aside.

While at Kipushi, we also befriended the very nervous and aged African ‘janitor/watchman’ at the magnificently established and manicured but deserted Belgian Cercle Sportif Club on the other side of the border. He was a useful fund of local information. All the Belgian ‘whites’ had left without taking the contents of a magnificent display of silver trophies and cups for every competitive activity imaginable, from canasta, billiards and bridge, to soccer and tennis; this included some pristine un-engraved trophies. Rather than leave the collection for the UN, or unruly CNA, or other rampaging brigands or the mercenaries, we felt, that as a new battalion, we would need some ‘trophies’ to get our inter-company sports programmes started, so we ‘borrowed’ the lot and gave the janitor a receipt for the loan. I do not know if the battalion was ever asked to return the loan.

We soon learned that any nervously chattering, disorganized and white- or light-blue-helmeted group we encountered were likely to be Swedes or Ethiopians. The French mercenaries would remain stock-still and threateningly quiet in their camouflaged uniforms, as would the Indian Army Gurkhas. We’d go on with our own businesses unless they were seen to be up to mischief; then we would make contact and investigate their purpose. They usually withdrew.

Soon after we arrived at the Kafue Bridge position we had a badly wounded soldier who had been shot through a lung by a nearby friend who had been assembling his recently cleaned Bren gun that had fired one round as the last movement of assembly was done. Unfortunately, the loaded magazine had been left on the weapon. We had no trained army medics with us, only some lads who had done first-aid courses as civilians, and our wounded soldier needed emergency surgery by a doctor; we’d learned that a French mercenary doctor was the only one in the area. David Parker and Sergeant Lourens, with panache and purposeful bravery, single-mindedly and swiftly swept aside any interference to their movement until they encountered the French mercenaries near Elizabethville. They explained that they needed a doctor urgently for one of our wounded lads. Sadly he died on the operating table and the nuns provided a superbly crafted wooden coffin for us to take back his body. This loss was felt deeply by 1 Platoon, and the lad cleaning the Bren was devastated, but there was little time for grieving as we quickly had to get on with our tasks. It was my first experience of accidental fratricide; unfortunately it happens too often in war, especially through sheer misfortune or carelessness in combat. Longer training and experience may have prevented this accident but urgency and psychological pressure may also have been culprits.

The mercenary doctor was rumoured to be Dr. Paul Grauwin of Dien Bien Phu fame, but this was never confirmed. However, he looked similar to the photos I saw later of Major Dr. Paul Grauwin in Bernard Fall’s book, Hell in a very Small Place.

I had followed Parker and Lourens during their wild ride toward Elizabethville but I left them at the hospital and went to yarn with the commander of the mercenary force while the doctor was doing his work. I met him crouching with his small staff in a large culvert under the road near the Catholic chapel-cum-hospital where our wounded soldier and other mercenary and civilian casualties were being treated. There were a few apparently randomly aimed 81mm harassing mortar rounds listlessly crumping around (what the Americans would call ‘Harassing and Interdiction Fires’).

I advised the mercenary commander in my execrable French that we were to prevent any non-Rhodesian forces entering Northern Rhodesia and he should keep his men out. He agreed, as we were not their enemy. He then made the startling mixed adjective/adverb comment that he thought Zheneraal Mobutu was a ‘blacking fuck bastard’, and that the CNA were ‘sheety foullis’—a rabble—and that they moved and fought as such. I also learned that the UN or Organizational Nationale Unie, ONU, was derisively termed Onyou—a new dirty word in the Congo.

By now, we had made contact with the local foreign mercenaries and found that almost an entire battalion étrangère parachutiste (French Foreign Legion parachute battalion) had deserted from the turmoil in Algeria and gone into the employ of the Katangese secessionist government. We also had seen and met some very unprofessional soldiers from within the polyglot UN force.

Who were our enemies and who were our friends? Bandits or brigands were obviously unlawful and needed to be subdued. The UN troops distrusted us and were unfriendly, we had to be wary of them; also they were not allowed to be on Rhodesian soil. They had earned a disgraceful reputation for their brutality (mainly Ghurkas) during their assault on the Katangese forces in Elizabethville. The mercenaries appeared to be neutral but could not be trusted. They only had loyalty to their paymasters. However, in some ways they were our friends, but again, as with the UN troops, they were not allowed to be there. In essence, we had to be wary of all, including, unfortunately, the unhelpful native commissioners and their staffs. So far, the Lunda tribe was being friendly. We were operating in a very ‘grey’ and fluid area and had little guidance from our military superiors who were probably in as big a quandary as we were. All I could do as a commander was attempt to achieve my mission and to ensure the safety and security of my men. Common sense was paramount. In most encounters with UN or other troops there would be a tense ‘stand-off’ until we established the situation, which in itself almost gave the initiative to the others. In fact, we never knew how close we had got, politically and tactically, to combat with the United Nations’ forces. It was very close according to Sir Roy Welensky, and conflict with the UN would have been without the covert or overt support of our ‘mother country’ and, once again, the perfidious Albion.4

With ‘local’ ground rules now messily established, we carefully but intensely patrolled by day and ambushed by night in the Kipushi region, and I presumed Barrett-Hamilton was doing the same in the Mwinilunga area. We made friendly contact with the locals in the Lunda kraal to the west of our Kafue Bridge position and base. They had already received instructions from their chief to help us. We advised them through their headman, in an appalling mixture of Chinyanja, Fanagalo, English and sign that they were not to move out of their kraal at night.

Our patrols made some contact with what they believed were UN patrols (some with light-blue helmets) and perhaps CNA rampaging mutineer groups or other bandits in our area. Some warning shots were fired which caused the opposition to disperse rapidly and disappear. Therefore we were now well aware that some ‘hostiles’ were coming over the border to see what was on offer. We offered them little happiness or friendship, and we patrolled even more intensely. Perhaps some were ‘tsotsi-type’ locals and out-of-work mine staff from the now-idle copper mines who were looting and taking advantage of the shambles and lack of law and order in the Congo. We also found that many bandits had somehow obtained brand-new self-loading Fabrique Nationale 7.62mm rifles and ammunition, probably from the looted Kamina base (the once-Belgian NATO reserve weapons armoury and ammunition dumps) just north across the border from Solwezi. I was told by a nurse at the Solwezi dispensary that one unfortunate had injured himself by firing the rifle, apparently before removing the thick grease from the barrel.

Therefore, all strangers were now proved to be very dangerous and were to be treated with suspicion and caution. On one occasion, two UN Panhard armoured cars and two trucks, apparently ‘lost’, came blithely barging down the road toward our bridge. CSM Hannaway and I, the only trained 3.5-inch rocket-launcher crew in the company, scared them away with a single ‘shot across the bows’ as it were, of the leading Panhard. After giving us a short ineffective spray of light machine gun fire, the Panhards and the trucks reversed madly into trees and disappeared. They did not come back. They were probably some disoriented Swedes who had bypassed the border custom post, found a bush side-track and driven blissfully down it across the border. UN vehicles never again approached us.

1RLI Signals Platoon. Brady Barracks 1961.

Early days—Classical War training.

RLI private soldiers. Trevor Kirrane is crouched third from left.

A Royal Rhodesian Air Force Dakota DC-3 uplifts Belgian refugees from an airstrip in the Katanga Province of the Congo.

Hotchkiss-Brandt 60mm light mortar.

M1 81mm medium mortar.

LMG—Bren gun.

Down the road from Kipushi, to our northeast, came a constant but erratic flow of cars containing frightened and weary Belgian refugees from Elizabethville. We checked the occupants, the cars’ interiors and boots for weapons and let them move on. David Parker and Sergeant Lourens sympathetically organized a ‘soup kitchen’ for the hungry. Many cars and light trucks, including new Mercedes, Renaults and Citroëns, ran out of fuel and were left abandoned. Others had been ambushed by various unidentified unlawful groups, the occupants slaughtered and the cars often burnt. This occurred especially along the road from Kipushi to Elizabethville, on which we had to move to get decent medical assistance from the mercenary forces or the nuns at the church.

While on a patrol to the south of the base on the banks of the Kafue River, David Parker and Sergeant Lourens also found the time to shoot a fine hartebeest and other smaller game. These ‘extra rations’ made for some delicious meals for us and with some of the locally obtained (and paid for) mealies (corn), went into the pots at our soup kitchens.

Our only recreation came from listening to the radio trying to get current information and, if I recall correctly on Sunday evenings, listening with poor reception, to the ‘hit parade’ hosted by David Davies, from Radio Lourenço Marques in Portuguese East Africa (Mozambique).

On one occasion, Corporal Greipel agitatedly came to our headquarters tent after a large group of Mercedes cars had been stopped. Greipel said, “Yurrah, sir! Jy moet take a kyk at this.” There were two or three cars with their boots and odd suitcases stuffed with thousands of bundled Swiss franc notes. It was a small convoy led by a Monsieur Simba, the Katangese foreign minister, and his family, plus entourage. He was, we were told, moving south to Lusaka to negotiate with agents of the Federal government. We told him it was now safe to travel south, and relieved them of a large number of weapons, including some brand-new 9mm Browning pistols and two superb, unused 7.62mm Belgian Fabrique Nationale (FN) fibre-glass-stocked, self-loading rifles (SLRs), with much 7.62mm and 9mm parabellum ammunition. We added these to the pile in our headquarters, but I kept one FN SLR for my own use until after we left the area, when I handed it over with all the other confiscated weapons to the BSAP in Bulawayo.

On an evening not long after the Simba incident, a dusty Mercedes, with its radiator grill splattered with expired guinea fowl, sped up to our checkpoint from the west and braked rudely in a cloud of dust. As it was going toward Kipushi and the Congo, it was interesting. Driving the car was a man with an Afrikaans or a Dutch surname and a ‘lah-de-dah’ Etonian accent. Hugh van Oppen was his name and he told us he was on a special mission for the Federal government. As he had a diplomatic passport, we queried no further, gave him a mug of tea and some hot stew while my men scraped off the many dead guinea fowl for better use later. He then sped off in another spray of dust. He was in a hurry. I do not think he had expected us to be there, because when our sentries temporarily relieved him of his weapon, he was very reluctant to let it go. He also had two loaded and cocked 9mm pistols and some tear-gas canisters on the floor of his vehicle. I thought he was a pretty bold and brave character, but we never saw or heard of him again.

Our patrols were making occasional light contact with UN and some unidentified armed groups. Our base was probed, whether by intent or accident we will never know. We had nights when shots, primary and detonating mortar rounds and flares could be heard and seen constantly from north of Kipushi and perhaps Elizabethville, sometimes closer. I could see and feel that our men, ‘green’ soldiers mostly, were getting a little twitchy. Once there was a mild flap, and a few wild harmless shots, when a returning fighting patrol led by an Australian, the experienced Corporal Crampton who I believe had fought as an infantryman against the Chinese in Korea, had forgotten the password. A few pithy swear words later and all could stand down again.

At dusk on the same night, a small group of people suspiciously approached from the west (as we were oriented east, it seemed from almost behind us). Lights had been seen and, as I did not expect the average kraal dweller to be out that late using torches, I was even more suspicious. We stood to. I had not had much chance for a cohesive all-round defence because we were patrolling with three half-section fighting patrols out, and the rest of the platoon spread thinly throughout the company-sized defensive position west of the bridge, mainly as double-sentries, and a third of the platoon resting, if possible. It was not possible now, and I had to see if we could disperse the group without too much fuss. After his pleading to do so and against my wishes, I had allowed David Parker to take out an ambush patrol. So, leaving the cool and capable Sergeant Lourens in command of the base, and, perhaps somewhat recklessly, I took out a ‘recce’ patrol of three bold men and cautiously crept and crawled toward where we had been told the group had paused. We got close enough to smell them and could hear whispering, which seemed to be in a Bantu language, so I assumed they were probably not UN troops but were probably CNA mutineers or brigands who had been causing problems with the local Lunda kraal dwellers. The three of us knew exactly where they were and as it was obvious they hadn’t seen or smelt us, I challenged them quietly in Chinyanja, French and English. They fired a shot so the three of us fired in their general direction, with me using my newly acquired and only once-tested FN SLR. We heard them jabbering incoherently as they scampered off. We crept forward and found no bodies, but one had dropped his rifle and we could feel and smell some warm blood on the rifle and on the ground. It was another new FN SLR and it joined our growing collection. This action quickly raised the spirits of our men.

During quiet periods our company signallers listened to much gibberish on nearby UN radio frequencies and they found that the UN’s Canadian signallers were often using, between themselves, the same NATO Slidex cards that we had. The information that we sometimes gleaned from this was seldom useful at our level because we did not have the same maps as theirs. However, it was fun to do, because though they conversed in rapid Canadian French, the Slidex cards were in English.

RLI 1st XV rugby team, 1961. Standing (left to right): Pte. Douglas, T.; Pte. Lloyd-Evans, L.; WOI (RSM) Reid-Daly, R.; L/Cpl. Meecham, R.; L/Cpl. Higgins, M.; Capt. T. M. Davidson; L/Cpl. Boyd-Sutherland, A.; Pte. Lotter, P.; Cpl. Liebenberg, C.

Seated (left to right): Cpl. Treloar, G.; L/Cpl. Young P.; Col. J. S. Salt (Area Commander Matabeleland); Major J. Essex-Clark (Captain); Lt-Col. W. Godwin (Acting CO); Pte. van Eeden, D.; Sgt. van Zyl, B.

Seated in front (left to right): Pte. Gillispie, I.; Cpl. Robinson, B.

The RLI rugby team (hooped jerseys) in action at Hartsfield, Bulawayo, 1961.

We also found that the short-strip Kipushi airfield lay astride the border. We controlled most of it by day, but at night it was often used by the mercenaries flying a very quiet Dornier STOL aircraft, which seemed to look somewhat like a larger version of a de Havilland Twin Otter. It would bring in ammunition and weapons and the odd person for the Katangese forces, and evacuate mercenary casualties, to where I don’t know, probably by some special clandestine arrangement into an airfield near a hospital within Federal territory. Although we reported the clandestine activity at the airfield we were told not to interfere, so we did not. RRAF Percival Provost aircraft also used the strip by day to bring us urgent written messages and desperately needed batteries or lightweight equipment so, in a way, we shared the strip without fuss.

Also in the Kipushi area, and in most cases after the event, some of the young men of A Company witnessed some unsavoury and disgusting incidents of savagery by the CNA or local brigands. These incidents they will probably never forgive or, unfortunately, ever forget. On one occasion, when checking activity in Kipushi, the caretaker at Cercle Sportif mentioned to me that there had been killing of the nuns (les soeurs) at the dispensary across the road. We investigated only to find that the nuns and a civilian male assistant had been cut up and strung up naked, and the medical stores ransacked. The lads with me were shocked and speechless, as was I, except for a few pithy oaths. We got the help of nearby locals to bury them with the assistance of the dispensary’s gardening tools. The assassins, whoever they were, had also shot the dogs and thrown them in the nearby filthy and littered creek in which lurked some well-fed crocodiles. The town dogs seemed not to be hungry either. The flies in the area were intense while we were doing the work.

During our long stay at the Kafue Bridge, our CO, John Salt, visited us once and with him was Major-General Bob Long, the Commander of Rhodesian Forces. This visit is memorable for one magic moment. Both Salt and Long had been astonished to find us in a well-knit but light-on-for-men, defensive position. I don’t know what they had expected to find, but we were obviously very differently deployed and secured to any other element of the battalion that they had visited. Bob Long wanted to inspect the position, and was delighted that he could give it a thorough looking-over, checking on fields of fire, home-made obstacles of thorn bush, and even the sentries at the water point got a chat from him. Of course, as do all generals when chatting to their men, he asked each man, “Where do you come from, lad?” When we reached Corporal Mulder, an excellent soldier and a dyed-in-the-wool Afrikaner, sitting behind his loaded Bren in his trench under his overhead cover, the general crouched down to see Mulder and popped the standard question to which Mulder promptly replied, “Here, sir!” It took a few moments of tangled misunderstanding and translated sentences to determine that Corporal Mulder hailed from, if I recall correctly, somewhere near Pietersburg in the Northern Transvaal (now Limpopo Province). Whenever and wherever I met General Long after that, he would always refer to that moment with much glee and satisfaction. “Aaahh … Essex-Clark,” he would say, “It’s Mulder-from-here, sir!”

Another strange incident while we were at the bridge was when I suddenly saw a pair of black sharp-toed ‘spivvy’ shoes, dark short socks and shorts outside my shelter cover as I was trying to get some sleep in the back of my Land Rover one afternoon. They belonged to a smart Belgian and he wanted to speak with me, so he had been warily escorted to my tent by my driver, Corporal van Eeden. What he wanted was extraordinary. He wanted to employ my whole company for Union Minière to fight for Katanga as mercenaries. He was offering huge sums of money for us to do so. He was told abruptly and forcefully that we were not interested and that he would be immediately escorted back to Kipushi without any further contact with my men.

These have been the stories from a single company of the RLI. I had no idea what the rest of the battalion, or even what 2 Platoon at Mwinilunga was doing; primarily because we did not have a reliable battalion radio net—radio types and distances often precluded this. Also, time and space meant that we could have assisted no other element of the battalion nor they us.

Then it was over and we returned to Brady Barracks. When I looked at my younger men as we were returning, I felt (as I wrote in my biography5): ‘I was shocked by the change in my men. My puppy-fat, anxious and chattering young boys had become a team of confident teak-hard men, eagle-eyed, silent and calm. The change from naïve and excitable youth to lean and knowing warrior was sad.’ Their speech was now constantly laced with profanities which took much time to abate.

Thus it was, and will ever be so with young soldiers.

We arrived back at Brady Barracks and normal life to find we now had a superb swinging regimental quick march, The Saints go marching in, and a proposed mascot, a cheetah. We spent much time tidying up the left-overs from our Northern Rhodesia–Congo border deployment in stores accounting, courts martial and removing the less suitable soldiers from the battalion. We also readied ourselves for the move to our new barracks at Cranborne in Salisbury. 1961 ended with a series of courts martial at Brady Barracks, following our deployment to Northern Rhodesia along the Congo border.

There had been clever soliciting in the pubs in Bulawayo and advertising in the Rhodesian newspapers for mercenaries to earn ‘quick money’ by assisting the Katanga secession. Some of our soldiers had been sucked in but had returned. I was asked by some of my A Company soldiers to defend those who had illegally disappeared to make that ‘quick money’ and had been charged with desertion. Those charged had returned, disappointed and feeling guilty. It was then my duty to defend them to the best of my ability. Initially, I thought their chances of being ‘not guilty’ were nil, but after some research, I realized that to prove desertion, the prosecution had to prove their intent to leave the Army permanently. There was of course no evidence to prove this. They were greedy, yes; ill-disciplined, yes; absent without leave, yes; but as they had returned of their own free will and because they were standing there in the court, I challenged that they had no case to answer. That no alternative charge of ‘absence without leave’ had been added was extraordinary. Therefore, irrespective of my proving mitigating circumstances such as their need for quick funds, to satisfy such as one who had caused the pregnancy of both his girlfriend and her mother (and I had brought those two ladies into the courtroom as witnesses, not to character but only to circumstance), the court, guided by the delightful Major Lindsay Seymour, the senior legal officer in the Army, agreed that there was no case to answer and their charges were dismissed.

Ferret armoured cars on manoeuvres.

Fortunately, I had been studying the Manual of Military Law very thoroughly in preparation for my promotion to major and staff college entrance examinations, and found legal and technical loopholes in many of the charges. Nevertheless, I soon also found that I was not popular with the hierarchy for doing so. However, in a few of the later cases I defended, the men were as ‘guilty as sin’ and punished accordingly, without any regret from me, because I had defended them to the best of my professional ability. In doing so we had also rid ourselves of some undesirables.

I returned to Bulawayo with the nauseous effects of yellow jaundice that laid me miserably low during my Christmas break in Salisbury. Our British Army-attached Regimental Medical Officer, Captain John Taylor, soothed me through this. While laid up with this malaise I missed the one battalion social event that I would dearly loved to have attended—an officers’ mess dining-in-night in our brand-new mess at which Sir Roy Welensky (the Prime Minister of the Federation) made a presentation of silver to the officers. If I recall correctly, the presentation was a silver port-barrel and some minor items. I had admired Sir Roy and his achievements under enormous international and internal pressure, and would have enjoyed meeting him.

During the last moments of 1961, John Salt told me, with some astonishment, that I had passed my ‘promotion to major and staff college entrance’ exams well (my marks surprised even me). I was promoted to substantive rank and selected to attend the British Staff College at Camberley in 1963. This was a satisfying moment in my career, particularly as my confidential report from John Salt had not recommended that I do so.

An interesting point—when the RLI was first formed from 1 Training Unit many of us were still wearing RNSC, RAR or other cap badges, and regimental accoutrements (such as lanyards, garter flashes, etc.). The first CO, John Salt, and the first 2IC, Bill Godwin, never transferred from their parent unit (RAR) to the RLI. I was one of the few officers who formally changed, much to the annoyance and consternation of others who kept their allegiance to their parent units. I wrote and replied to my detractors by telling them that the RLI was a new unit, needing identification, I was commanding 120 men wearing the RLI badge and therefore, for reasons of leadership and loyalty to my men, I would become one of them in spirit, attitude and uniform. Nevertheless, even some of those who did not change their allegiance to their parent unit wore the RLI badge and accoutrements. I believe they did so quite falsely, deceptively, and dishonestly. But there you go. I was considered almost a traitor! To me, the men I was serving and commanding came first. Incidentally I was one of the first to wear an RLI uniform (rifle-green jacket and trousers) with accoutrements (black Sam Browne belt with silver buckle and scabbard hooks, RLI lanyard, the RLI green and silver stable belt with field dress) in the UK when I attended the Staff College at Camberley. The beret came later. However for our dress uniform (including our diggers) we wore the uncomfortable rifle-green peaked caps.

To most of the others in the Rhodesian Army we youngsters without any World War II experience, African language skills, or BSAP service, were upstarts and unwanted outsiders! All in all, I felt more at home in the RLI than I ever did in the SRSC, RNSC or RAR. In the RLI we were a family.

Postscript: A tale about Brian Barrett-Hamilton. When I went into his room at the offcers’ mess at Cranborne to discuss a training matter, there was a large framed photo of a very military gentleman in his room alcove. I asked Brian if it was his father.

“No, sir,” he replied, “That is Jesus Christ!”

Somewhat astonished I said, “What do you mean?”

“That, sir, is Warrant Officer J. C. Lord, Academy Sergeant-Major at Sandhurst. He was nicknamed ‘Jesus Christ’ for his initials,” he replied. “When I leave this room I look at that picture and I don’t allow myself to put a foot wrong!”

It gave me a good laugh at the time but a year later, after I had listened to J. C. Lord address the Staff College at Camberley, the first WO or NCO to ever do so, I could understand. The German student friend sitting next to me muttered, “Aahh! Now, Dikka, at last, I unterstant vy zer Breetish Army is so koot!” …

In a footnote to Digger’s postscipt concerning the legendary Sandhurst RSM there is the well-told tale that on one occasion, when welcoming a platoon of new officer cadets, one of whom was Prince Hussein of Jordan, he said, memorably, “You will address me as ‘sir’. I will address you as ‘sir’. The only difference being that you mean it.”

1 J. R. T. Wood ‘The Rhodesian issue in historical perspective’ as quoted in Challenge p361, Ashanti 1989

2 The original Selous Scout Regiment. Not to be confused with the later famous infantry regiment of the same name

3 Salt died in September 1991, aged 77, as a result of injuries sustained in a hippo attack on his craft when canoeing on the Zambezi. In tribute a friend (and later CO of 1RAR), Brigadier David Heppenstall wrote: ‘While his death … was tragic, I cannot help feeling that it was the sort of way that any old Rhodesian would like to go.’ Lion & Tusk (magazine of the Rhodesian Army Association) Vol. 3, No. 2, November 1991

4 Sir Roy Welensky, 4000 Days—The Life and Death of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland p212, Collins, London 1964

5 John Essex-Clark, Maverick Soldier—An Infantryman’s Story p58, Melbourne University Press, 1991

References

Geoffrey Bond, The Incredibles, Sarum Imprint, Salisbury, Rhodesia 1977

Paul Wellburn’s recollections are from Lion & Tusk Vol. 4, No. 2, November 1992