CHAPTER VII

The Earlier Dialogues of Plato

*

The three great dialogues of Plato which deal with problems of political thought are the Republic, the Politicus, and the Laws. Of these the Republic belongs to the first period of Plato’s life, and may have been finished by the year 386 B.C. in which he founded the Academy; the Politicus may be dated about 360; and the Laws, the last work of Plato’s pen, was published posthumously, after his death in 347. But there is a number of early dialogues, prior to all of these, and probably written before 386, which are largely concerned with matters of political theory. These are all Socratic dialogues proper, and they are all concerned with the exposition and vindication of the teaching of Socrates. The Apology and the Crito, in dealing with the life and death of Socrates, raise problems of the relation of the State to the individual. The Charmides and the Laches, the one immediately concerned with the virtue of self-control, the other with that of courage, both issue ultimately into larger questions: on the one hand the conception of the unity of virtue leads to the question of the relation of the virtues to virtue at large; on the other, the conception of the State as the promoter of every virtue leads to the question of the relation of moral life to political society and ‘political science’ – a question also discussed, incidentally, in a passage in the Euthydemus. The Meno, in discussing knowledge and instruction, necessarily discusses the nature of political knowledge and the possibility of instruction in politics; and a similar problem is also discussed in the Protagoras. Finally, in the Gorgias Plato is concerned with the value of the study of rhetoric as a preparation for the life of politics; and he is led to attack the basis of false principle which underlies, in his view, the teaching and the practice of oratory.

1. THE APOLOGY AND THE CRITO

The Apology is an attempt to justify Socrates. Suspected by the democrats of being the head of an aristocratic coterie, he had been accused of corrupting the youth and disbelieving in the gods of the State, and he had been brought to trial by his accusers. The problem which confronted him at his trial was the problem of Antigone, when Creon had issued his edict against the burial of her brother Polynices. Should obedience be paid to the will of the State, or to the sense of justice with which it conflicted? Should he conform by promising silence, and obey the law by such conformity; or should he satisfy his sense of what was right by refusing to refrain from open warning and denunciation? It is the question which has always confronted the martyr; and in the spirit of a martyr Socrates gives his answer. What he has done is the command of God. ‘Acquit me or condemn me: I shall never alter my ways’ (30 A–C). In the name of something higher than the law of the State he defies the law, as men have done in all ages. But this is only one side of the matter; and another and complementary side is presented in the Crito. In this dialogue Plato supposes that Socrates is tempted by Crito to escape from the prison in which he lies condemned to death for the answer he has given. If he escapes, he will again disobey the law, which has commanded him to abide in prison, and to die there for his first disobedience. Shall he twice sin against the law? If he had been forced to defy it once for conscience’ sake, he will not defy it again for life’s sake. He has already done a grievous thing: he has gone about to overturn the law. He will now by his obedience recognize its claims, and as far as in him lies, he will help to establish its sanctity. In teaching this lesson, Plato imagines a dialogue between the Laws of Athens and Socrates. ‘So you imagine’, the Laws inquire of Socrates, ‘that a State can subsist in which the decisions of the law must yield to the will of individuals?’ ‘But the decision of the law in my case was unjust.’ ‘But the law has none the less a double claim on your obedience.’ Plato proceeds to expound the nature of this double claim. In the first place, the law, regulating as it does marriage and the nourishing and education of children (and Socrates admits that he has no objection to urge against this action of law), is in a real sense the parent of every citizen.1 By law the citizen is legitimately born into his citizenship; by law he is educated into the capacity to use his citizenship. By the grace of the law he is what he is; and as a child owes obedience to his parents, so, and for the same reason, a citizen owes obedience to the law. It is the law that has made Socrates, and not he himself: shall he quarrel with his maker? The conception is put in a Greek form, but it is a conception eternally true. We are all the product of a number of influences, which have shaped our character and given us our powers – our School, our Church, our State; and we owe a debt of gratitude for the gifts which we have received. It may be our duty to reject them, in the name of something higher; it is also our duty to respect them. The debt must be all the more keenly felt, and the more carefully repaid, if all these influences are, as they were for the Greek, gathered into one, and if they appeal for recognition, as to him they did, with a single voice. But there is, Plato feels, still another claim of law upon the individual. If he is bound as a child to repay it for its training of his youth, has he not, when he came into man’s estate, entered into an implicit covenant (ὡμολόγηκεν ἔργῳ) to obey the laws?1 He has liberty under the law to emigrate: if he prefers to stay, at an age when he realizes the obligations which he incurs by staying, he enters into an agreement (συνθήκη), none the less binding because it is not expressed, to discharge those obligations.2 There is here no idea that the State is based originally on a contract of individuals and owes its claims to concessions made in that contract: on the contrary, we have just seen that to Plato the relation of the State and the individual is not one between two parties to a contract, but one between father and child. The Sophists were the ‘contractarians’, and Plato was the convinced enemy of their views, teaching rigorously the inevitable nexus which binds man to man in a State, and – as a corollary – the dominant claim of the State upon its members. What Plato means is that every man who regards himself as a member of a State has thereby really and implicitly, though not verbally and explicitly, subscribed to the obligations of membership. He has claimed rights, and has had them recognized: he has acknowledged duties, and is bound to fulfil them. This is implied in membership of the State: it is implied in the membership of any group. No man can belong even to a debating society without incurring obligations of subscription and of orderly behaviour, which are the correlatives of his right to make or to hear a speech. The fact that he does not resign his membership is a standing proof of his acknowledgement of those obligations. This is Plato’s contention; and thus the gist of the Apology and Crito comes to this: ‘Obey the law, and obey it cheerfully, where a material interest is at stake: otherwise you are a disobedient son and a faithless partner. Disobey it only, and disobey it even then in anguish, when a supreme spiritual question is at issue.’ It is the exact opposite of Hobbes’ view, that a man should submit in matters of conscience, and only revolt to save his life.1

2. THE CHARMIDES, EUTHYDEMUS, AND LACHES

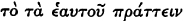

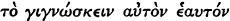

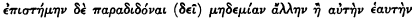

While in the Apology and the Crito, Plato writes of the death of Socrates, in the Charmides and the Laches, and to some extent also in the Euthydemus, he writes of his life and teaching, and indicates the methods by which he sought to convey his teaching. The Charmides contains a discussion of the nature of temperance or self-control – a discussion which, in the true Socratic manner, is rather aporetic than didactic, and directed rather to stimulate thought than to give a solution to the problems by which thought is confronted. One of the many definitions of self-control suggested in the course of the dialogue may be noticed here, because it anticipates the definition of justice or righteousness which is given in the Republic. Self-control has been defined, ‘by somebody’, as ‘doing the things which belong to one’s own self’ ( : 161 B). The definition is not accepted, and indeed it is not really discussed. Instead of being taken in its obvious sense, that men should confine themselves to the work of their own particular capacity and station, it is twisted into the opposite sense, and interpreted to mean that each should do everything for himself, and make his own clothes and shoes and everything else that he needs (161 E). This would ascribe temperance to the Highland shepherd of whom Adam Smith wrote in the Wealth of Nations, who was ignorant of any division of labour; and Plato readily objects that a temperate State, which must, as such, be a well-ordered State, can hardly be composed of Highland shepherds (162 A). But though it is thus dismissed, the definition recurs in another form in the course of the dialogue, during the discussion of another and alternative definition. Self-control, it is now suggested, may be defined as self-knowledge (

: 161 B). The definition is not accepted, and indeed it is not really discussed. Instead of being taken in its obvious sense, that men should confine themselves to the work of their own particular capacity and station, it is twisted into the opposite sense, and interpreted to mean that each should do everything for himself, and make his own clothes and shoes and everything else that he needs (161 E). This would ascribe temperance to the Highland shepherd of whom Adam Smith wrote in the Wealth of Nations, who was ignorant of any division of labour; and Plato readily objects that a temperate State, which must, as such, be a well-ordered State, can hardly be composed of Highland shepherds (162 A). But though it is thus dismissed, the definition recurs in another form in the course of the dialogue, during the discussion of another and alternative definition. Self-control, it is now suggested, may be defined as self-knowledge ( : 165 B). If it is knowledge, Plato makes Socrates rejoin, it must, like other kinds of knowledge, be knowledge of a definite object; and what is that object? The author of the definition replies that it is threefold. Self-control is knowledge of itself; it is knowledge of all other branches of knowledge, which enables its possessor to use them temperately; finally, it is knowledge of the difference between ignorance and knowledge, in virtue of which its possessor knows the limits of his own knowledge (166 E–167 A). The reply contains elements which are genuinely Socratic and genuinely Platonic. The one knowledge which Socrates professed to possess was knowledge of his own ignorance

: 165 B). If it is knowledge, Plato makes Socrates rejoin, it must, like other kinds of knowledge, be knowledge of a definite object; and what is that object? The author of the definition replies that it is threefold. Self-control is knowledge of itself; it is knowledge of all other branches of knowledge, which enables its possessor to use them temperately; finally, it is knowledge of the difference between ignorance and knowledge, in virtue of which its possessor knows the limits of his own knowledge (166 E–167 A). The reply contains elements which are genuinely Socratic and genuinely Platonic. The one knowledge which Socrates professed to possess was knowledge of his own ignorance

Nosse nihil dixit se nisi nosse nihil

and we shall find Plato himself, in the Euthydemus and again in the Politicus, suggesting that there must be a master-knowledge which controls the use and application of all other branches of knowledge, and identifying this master-knowledge with the art of politics or ‘political science’. In the Charmides, however, doubt is cast alike on the possibility and the utility of a knowledge so vast and embracing. In the first place it is hardly possible; knowledge, as such, must always be knowledge of a specific and related object, and the three objects suggested will scarcely satisfy that condition. If it had been possible, it may seem at first sight that it would have been supremely useful. If men could know the difference between knowledge and ignorance, for instance, both in themselves and in others, they would have an unfailing clue to the conduct of life both for themselves and for those whose lives they controlled. Never attempting themselves to do what they knew that they did not know, but leaving it always to others who knew; never allowing others whom they controlled to do anything they did not know, and could not do well, they would institute a perfect life free from all error. A house inhabited in temperance, after this fashion, would be a house well inhabited: a city governed in temperance would be a city well governed: with error gone, and with truth for guide in every action, men would live well, and living well they would be happy (174 E–175 A). So, at any rate, it seems; and yet it may be true, after all, that such knowledge, as it is not possible, is not really useful either. The perfect control of life by a knowledge perfectly conscious of itself and its own limitations might not ensure happiness: the perfect division of labour, and the limitation of every man to the work of his particular capacity, might not bring a State any nearer perfection. Perhaps the only knowledge that gives happiness is the knowledge of good and evil (174 B); and perhaps this is the knowledge which is self-control. Perhaps, again, even this knowledge is not useful, at any rate in the sense that it produces a definite utility; and self-control, if this is self-control, is after all useless (174 E–175 A).1

The aporetic method and conclusion of the Charmides must not blind us to the suggestions which it throws out – suggestions which we shall find adopted and carried further in the Republic. One of these suggestions recurs, and is amplified, in a passage in the Euthydemus (288–292 E). This is the suggestion of that master art or knowledge by which all other arts or branches of knowledge are governed. No knowledge, Plato argues, is useful unless we know the purpose for which we should use what we know. Even if a man had knowledge so that he could produce immortality, it would profit him nothing unless he knew how to use immortality. A knowledge of the proper use to which any branch of knowledge should be put is thus a master knowledge fundamentally necessary to human life. A doctor, for instance, knows how to heal; but a further knowledge is needed to decide the use to which his art should be put. He heals both the just and the unjust; and yet it were better and more profitable for the unjust man to die than that he should be healed and live (Laches, 195 C–D). Without a master knowledge to control them, other branches of knowledge also are only unprofitable servants; and this knowledge, when it is present, must determine the end for which they are all to be used, and fix, in its light, the occasions and extent of their use. This master knowledge is not rhetoric, or the art of the parliamentarian. A composer of set speeches can make a speech, which may act like a spell on a popular court or assembly; but he is as ignorant as the doctor of the use he should make of his art, the purposes which it should serve, and the times and seasons when it ought to be exercised (Euthydemus, 289 D–290 A). Nor is it again a knowledge of the art of war:2 the successful general may capture a city or an army, but he has to leave it to the statesman to use the victory which he is not competent to use himself. It may seem, then, as if the master art were that of the statesman, and as if his were the art that is the cause of right action in every State—that sits in the stern of the ship, always steering, everywhere ruling, and making all things serve their appointed use (291 D). Be this as it may, one thing is clear: this master knowledge, like every branch of knowledge, must produce some result. The physician produces health: the husbandman food: what is produced by those who possess the master knowledge? They must certainly produce wealth, liberty, harmony; but these are neither good nor bad – they are in themselves indifferent, and everything depends on the use to which they are put (292 C). What statesmen must produce above all – and this is far from indifferent – is knowledge, the true good which gives men happiness. But must they produce knowledge among all, and must it be knowledge of all things; or must they produce it in some, and must it be knowledge of one thing? … Here the argument ends, once more, as in the Charmides, on a note of doubt; but the suggestion which it makes is none the less important, and we may see Plato moving gradually to the conception of a State perfectly controlled by a perfect knowledge which is a knowledge of the final purpose that each and every human activity should serve – a State in which the statesmen who possess such knowledge communicate it to others in their degree1 – a State, in a word, which is ruled, as Plato can definitely urge in the Republic, by philosopher kings in the light of the Idea of the Good.

The Laches, which is concerned with the nature of courage, but which culminates in a theory of the unity of all the virtues, points to a similar conclusion. The sons of two famous Athenian statesmen – Aristides ‘the Just’ and Thucydides the son of Melesias – are introduced, in the beginning of the dialogue, in the act of discussing the education of their sons. They complain that their own education was neglected by their fathers (it is a favourite theme with Plato that Athenian statesmen have always failed to train their sons in their own ways); and they profess anxiety about the education of their own sons, more particularly in military exercises. This leads to a discussion of the nature of the virtue of courage, which it is the object of any military education to inspire. It cannot be merely blind endurance, which faces risks in ignorance, and without knowing whether the purpose to be served justifies the risks to be encountered. It must be a seeing virtue, based upon knowledge; and it is accordingly defined as knowledge of what is to be feared, and what is not to be feared, both in war and on all other occasions (195 A). Courage, therefore, is no common animal habit: it is the quality only of a few, because there are only a few who can attain the knowledge which is its necessary condition (196 E). That knowledge is elevated to a still higher plane in the course of the dialogue. Courage involves judgement of good and evil, whether past, or present, or to come; the brave man must know, in virtue of a permanent knowledge, the evils which are to be feared, and the good which is not to be feared. If this be so, courage is not so much a part of virtue as the whole of virtue (199 E): that is to say, it cannot be present unless the whole of virtue is present. This is because virtue is a unity; and to have one virtue fully, in virtue of a proper knowledge, is to have all the virtues, since such proper knowledge is the full knowledge that ensures full virtue. Thus the end of the dialogue is in a sense nothing, for the differentia of courage has not been discovered; but in another sense it is much, for the unity of virtue has been the conclusion of the argument. And that is a conclusion which squares with the conception of a master knowledge in the Euthydemus. He who has virtue, and the perfect knowledge which belongs to virtue, has the master knowledge which will guide the State.1

3. THE MENO, PROTAGORAS, AND GORGIAS

The third and last group of the earlier dialogues of Plato is composed of the Meno, the Protagoras, and the Georgias. While the group with which we have just been concerned represents the positive side of the teaching of Socrates, this group represents the negative and critical.2 The three dialogues which it contains are all addressed to actual States and their actual practice; and it is the aim of them all to explain the principles on which such practice, consciously or unconsciously, rests, to prove its shortcomings, and to show the necessity of true and genuine knowledge for any true and proper action. Plato thus brings Socratic theory into contact with actual life; and while, as we shall see, the result of that contact is a partial justification of actual life, it is also – less perhaps in the Meno and the Protagoras than in the Gorgias – its condemnation, and the justification of Socratic theory. That theory, Plato urges in these dialogues, is incompatible with States as they are. The death of Socrates is itself the supreme proof that the lessons he taught in his life can never be realized in an actual State. If the State as it stands could put to death the man who simply taught the necessity of the rule of scientific knowledge, à fortiori it would never tolerate the actual realization of that teaching. It follows – and this is the conclusion which we find Plato gradually drawing – that the drastic reformation of the State is the prior condition of any attempt to enthrone philosophy. One must not merely preach the sovereignty of wisdom; one must seek to prepare a highway for its coming, and to ensure the conditions necessary for its rule. And this means the construction of an ideal State, so ordered that knowledge can find its proper place. It means, we may say in a paradox, the building of a Utopia, a city of Nowhere, in order that knowledge may find a place where it can dwell. Short of that, we can fall back only on the State as it stands, in a mood of pessimism, and admitting that there is no place to be found for the rule of knowledge, we must admit that Socrates taught the impossible.

This full conclusion is only attained in the Republic, and only attained gradually. As yet Plato is only concerned with the vindication of Socratic teaching against the practice of actual life. Socrates had taught the supremacy of the true or greater knowledge. Why then, it may be asked, do men attain such success as they actually attain without that knowledge; and is that knowledge again of such a nature that it can be made a subject of instruction and communicated to others? The justification of Socrates demands an answer to these questions; and in the Meno an answer is attempted. Here political virtue, or the quality of a good statesman, comes under discussion; and Plato admits that experience shows that good statesmen do not transmit their qualities to their sons or successors. Yet they certainly would, if they could; and it would therefore seem, after all, that Socrates was preaching the impossible, and that no instruction can make a good statesman. In reality it is not so. The reason why good statesmen cannot transmit a knowledge of statesmanship is not that it is not transmissible, but that they have no knowledge to transmit. Instead of a reasoned knowledge, connected by a principle, in the light of which it is lucid and teachable, they have only an instinctive tact, a sort of flair by which they can travel along the right path, though their eyes are holden from knowledge of the truth.1 Such an instinctive ‘right opinion’ (ὀρθή δόξα), ‘which is in politics what divination is in religion’, may lead men very far, and ‘having no understanding’, but ‘being inspired and possessed’, they may say and do much that is noble (99 C–D). But right opinion is incommunicable: one cannot teach an instinct; and it has the further defect that at a crucial moment it may fail. There is no guarantee that it will respond to every fresh problem: under a different set of conditions it may be utterly useless, because it is necessarily connected with mere use and wont. Only a reasoned knowledge illuminated by a principle will meet and master every demand of life; and such a knowledge, so methodized and unified, is a natural subject of instruction which one generation can hand on to another. The Meno shows how strongly Plato felt the two great advantages of scientific knowledge – first, that it could meet every emergency, and secondly, that it could be continuously transmitted. With a scientific training, statesmen would not need to rely on the inspiration of the moment, and States would cease to depend on the chance of finding an inspired statesman for every crisis. Training would give the statesman continuous inspiration: training would give the State a permanent dynasty of philosopher-kings instead of occasional ‘premiers of the people’. It was reflections such as these which impelled Plato towards the whole system of training proclaimed in the Republic and actually given in the Academy. The Meno foreshadows both, and shows Plato feeling for a way to bring life out of the domain of chance wedded to instinct, and into the sphere of art wedded to knowledge.

Much the same may be said of the Protagorm. In this dialogue not only Socrates, but the Sophist Protagoras also, appears as a champion of the position indicated in the Meno; and while in its course Socrates is made to confute Protagoras, we ultimately find that he only returns to Protagoras’ own view on a higher level. Protagoras begins with the assertion that as a Sophist or teacher he teaches political art (πολιτικὴ τέχνη), and that by his instruction men became good citizens, ‘able to speak and to act for the best in the affairs of the State’ (319 A). Socrates has two objections to urge against the possibility of any instruction in such a ubject. In the first place, while on a subject like shipbuilding nobody commands an audience in the Assembly who does not possess a technical knowledge of the subject, in affairs of State tinker and tailor are heard with a readiness which implies that there is no technical knowledge of political art. In the second place, there is the old difficulty: statesmen are shown by the experience of Athens to be incapable of communicating their wisdom to their sons. In a long speech Protagoras replies to Socrates’ difficulties. Underlying his speech is the assumption, which also underlies all the thought of Plato and Aristotle, that political art, or the quality of acting rightly in the State, is the same as virtue, or the quality of right action in general. Political art in this wide sense Protagoras regards as not, like specific arts, the quality of special individuals, but the common endowment of all mankind. This conviction he states in an apologue, which seems to represent his actual view of the origin of the State (supra, p. 71). He believes in a primitive state of Nature, and in the religious origin of political association. In the state of Nature men, while possessed of the arts of life, were destitute of political art, and though they had religion and language, they were almost destroyed by the beasts for want of the strength of political assosiation.1 Desire for self-preservation drew them into cities; but, still destitute of political art, they destroyed their own cities by internal dissension. At last Zeus came to the rescue, and ‘sent Hermes to them, bearing reverence and justice to be the ordering principles of cities and the bonds of friendship and conciliation’ (322 C). But while the arts had each been the property of a favoured few, Zeus gave the ‘political art’ of justice to all, since all must share therein, if the cities of men were ever to exist and prosper. And therefore it is that Athenians listen to tinker and tailor in affairs of State.

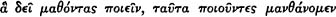

A deep truth is stated in this apologue. Mere aggregations of men do not form a State: an artificial unity maintained by artificial laws would be no sooner formed than broken. What is needed is the life-breath from on high – a common mind to pursue a common purpose of good life; and it is only in virtue of such a common mind that the State is real and vital. As Protagoras continues his argument, he hits intuitively on further truths. Punishment, he tells his audience, is proof positive that this virtue or political art, which is the life-breath of the State, can be transmitted and taught; for punishment is not the ‘unreasonable fury of a beast’ (324 B) or a retaliation for past wrong; it is administered with regard to the future, and to deter the criminal from doing wrong again.1 And not only does a preventive means like punishment imply that virtue can be taught: it is clearly explicit in a positive way in the educational system of the State. For youth, there is all the instruction of great poetry, with its admonitions, and its stories of famous men of old for imitation and emulation: there is music, which by its harmonies and rhythms makes the soul rhythmical and harmonious; and there is gymnastics, which makes the body fit minister of a virtuous mind. For manhood, again, there is the ensample of the laws, which guide men’s conduct not only by repression, but also by positive direction. Nay, outside all set and formal institutions for the teaching of virtue, Protagoras asks, is there not more? ‘Are not all men teachers of virtue, each according to his ability?’ (327 E). IS not society one great school of education? Merely by speaking our language to one another, we teach it unconsciously to the young as they listen; and what is true of our words is true of our deeds. Our lives are so many lessons, and some of us good teachers, teaching good, and some of us evil teachers, teaching evil. ‘All of us have a mutual interest in the justice and virtue of one another, and that is the reason why every one is so ready to teach justice and the laws’ (327 B). And if, as Socrates had urged, some of us are good teachers, and yet produce poor results, is it not merely that we have poor material? If Pericles failed to transmit his virtue and his political ability to his sons, it was not because he lacked knowledge, or even because the knowledge he possessed was such as to be incommunicable, but because the gods do not give their greatest gifts to all men, and they had not given them to his sons. In any case, his sons were educated in the general school of society, and they received the general and communicable gifts of the political art, even if they failed to inherit the inspired statesmanship of their father.

It may well seem that Protagoras has made a good defence both of the Athenian Assembly and of Athenian statesmen.1 He has defended the Athenian Assembly by the argument, which must always be a fundamental argument for the democratic cause, that in politics there is no distinction of professional and amateur, and that all men acquire a political instinct as readily as they learn their own language or pick up a tune. He has defended Athenian statesmen equally: they are not to blame if they cannot transmit to their sons the torch of a divine inspiration which descends as it lists. Nor has Protagoras only made a good defence of the political practice of Athens: he has said much which appears as Platonic as it is Protagorean. Much of the Republic – its whole scheme of education, for instance – seems like an expression of the ideas which Protagoras is here made to express. Just as in the Republic Plato begins by conceiving the State as an economic organization, based on division of labour, and then proceeds to lift it to a higher plane, conceiving it as a spiritual association in which each finds righteousness through the fulfilment of his allotted duty, so Protagoras, in the dialogue called by his name, begins by regarding the State as an institution for the preservation of life, and ends by regarding it as a common structure of mind erected for a common purpose of good life. Men may have the arts of life, and they may add to these some common machinery for the protection of life; but the mere economic association is in its nature selfish, even though the division of labour which it entails seems to promise mutual help, and by this selfishness it will be destroyed, unless the saving grace of ‘political art’ comes down to men with its gifts of righteousness and reverence.

So far, then, the teaching of Protagoras is confirmed by the teaching of Plato himself in his greatest dialogue. Yet Plato makes Socrates, in spite of all the acknowledged charm of Protagoras’ discourse, proceed to its confutation. He is wrong in distinguishing political art from all other arts as a common possession, and in holding that it is automatically communicated in the ordinary life of society: he is wrong, again, in believing that its highest reach is an incalculable and incommunicable instinct. The political art, like other arts, is the property of a few, and requires a special training; and its best practitioners, like the best practitioners of any other art, must possess a reasoned and transmissible skill. Politics is no field for the instinct of the masses and the intuition of statesmen: a State cannot rest on a basis of mere general knowledge (or ignorance) coupled with the saving grace of heaven-born statesmen; it needs philosophic knowledge and the trained ruler on whose presence it can always count if it possesses a system of training. Protagoras is right, it is true, in identifying the political art with virtue, and in holding that virtue can be taught; but virtue is a more arduous thing, and needs a more serious teaching than he allows. Perfect virtue is not an aggregate of qualities in which all men can participate, each in his different way. It is one and undivided, as Socrates proves by a discussion of the unity of virtue; and it is one in being knowledge. Perfect virtue is perfect knowledge, a perfect understanding of the world and man’s place in the world; and therefore it is only the few who can ever attain its possession. But just because it is knowledge, virtue can be taught, in a far truer sense than Protagoras had ever meant: it can be taught by every means, and can only be fully taught by all the means, that give men a perfect understanding of the world. Instead of many phases of virtue, uncorrelated with one another and only dimly understood – instead of the vague inculcation of these in an empiric fashion by the ordinary ways of punishment and education and law and social influence, which appeal more to instinct than reason – Socrates fixes his eyes on virtue one and indivisible, virtue which is perfect self-knowledge and therefore perfect self-mastery, virtue taught by the ‘scientific’ path of a full education, whose goal is a perfect knowledge of the world and thereby of man and man’s place in its scheme.

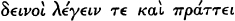

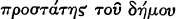

None of the earlier dialogues of Plato deals so thoroughly, or so drastically, with political questions as the Gorgias. The Gorgias, so named from the first teacher of rhetoric in Athens, is a treatise on oratory. The interest of Plato in oratory, as we may gather from the dialogue, is twofold. He is partly concerned with the art of rhetoric as a method of education: he is partly concerned with the actual practice of oratory as a means of acquiring office and influence. As a method of education, the art of rhetoric, as it was taught at Athens, dealt not only with form and style, but also with the matter and policy of public-speaking. What has been said above, of the school of Isocrates, may serve to illustrate the scope of such teaching; and we have to remember that Isocrates had founded his school in the first decade of the fourth century, and that it was perhaps already at work when Plato wrote the Gorgias.1 If there was anything which could pretend to dispute with philosophy the position of a master knowledge, or could put forward a rival claim for the guidance of life and affairs, it was this art of rhetoric, which professed to train men for politics, and to make them able to act as well as to speak efficiently ( ). While the teacher of philosophy had thus to be vindicated against the teacher of rhetoric, the philosophical statesman had also to be vindicated against the orator statesmen of actual Athenian politics. Oratory was rooted in the constitution and life of Athens, partly in the popular law-courts, partly, and even more, in the popular Assembly. With that Assembly supreme in the State, political influence and power naturally went to the orator who could influence and control its decisions. The art of public speaking has a large scope in the representative assemblies of modern States, where the skilled debater wins his way to office on a tide of speeches; but it had a still larger scope at Athens. In a representative Assembly the orator has to satisfy the critical sense of representatives who are in constant session and constantly handling affairs themselves: in the Athenian Assembly the orator had the easiest task of charming a popular audience which, whatever its native aptitude or its political experience, was liable to value a telling speech at a very high price. The unofficial ‘leader of the people’ (

). While the teacher of philosophy had thus to be vindicated against the teacher of rhetoric, the philosophical statesman had also to be vindicated against the orator statesmen of actual Athenian politics. Oratory was rooted in the constitution and life of Athens, partly in the popular law-courts, partly, and even more, in the popular Assembly. With that Assembly supreme in the State, political influence and power naturally went to the orator who could influence and control its decisions. The art of public speaking has a large scope in the representative assemblies of modern States, where the skilled debater wins his way to office on a tide of speeches; but it had a still larger scope at Athens. In a representative Assembly the orator has to satisfy the critical sense of representatives who are in constant session and constantly handling affairs themselves: in the Athenian Assembly the orator had the easiest task of charming a popular audience which, whatever its native aptitude or its political experience, was liable to value a telling speech at a very high price. The unofficial ‘leader of the people’ ( ) depended for his position on the command which he exercised over the Assembly; and Pericles himself, though he held the official position of στρατηγοζ, owed much of his actual influence to his oratory, and to the fact that ‘alone of the orators, he left his sting in his hearers’. In the Euthydemus, and again in the Politicus, Plato recognizes the orator as a serious rival to the true statesmen, and is at pains to distinguish them from one another. It is natural that he should devote, as he does in the Gorgias, a separate dialogue to the subject of oratory, and to the discussion of its basic principles and its real value. It is natural, too, that the view which he takes of oratory in that dialogue should be severely unfavourable, and that, writing of Athenian institutions from this angle, he should condemn them much more drastically than he does in the Meno or the Protagoras.1

) depended for his position on the command which he exercised over the Assembly; and Pericles himself, though he held the official position of στρατηγοζ, owed much of his actual influence to his oratory, and to the fact that ‘alone of the orators, he left his sting in his hearers’. In the Euthydemus, and again in the Politicus, Plato recognizes the orator as a serious rival to the true statesmen, and is at pains to distinguish them from one another. It is natural that he should devote, as he does in the Gorgias, a separate dialogue to the subject of oratory, and to the discussion of its basic principles and its real value. It is natural, too, that the view which he takes of oratory in that dialogue should be severely unfavourable, and that, writing of Athenian institutions from this angle, he should condemn them much more drastically than he does in the Meno or the Protagoras.1

The general view of oratory which appears in the Gorgias is expressed in the form of a classification of the arts which deal with the soul and the body of man. There is an art of the soul, we are told, which has for its object the soul’s health; and this art, which is the art of politics, has two divisions, the one legislative, the other judicial. Similarly there is an art of the body, aiming at the body’s health, and divided into gymnastics, which regulates the growth and action of the healthy body, and medicine, which heals its diseases. Legislation is like gymnastics; judicial action is like medicine. These are all real arts, and as such they have two characteristics; they are scientific and based on principles, and the aim which they pursue is the benefit and betterment of the objects with which they deal. But there are also sham arts, which are only empiric and spring from mere experience or routine, and whose aim is only to give pleasure and merely to flatter the senses. The dressing of the body to look healthy is the sham or simulacrum which usurps the place of gymnastics: cookery, pretending to care for the health of the body, is a sham which takes the form of medicine. What dressing is to gymnastics, that is sophistry to legislation: what cookery is to medicine, that is rhetoric to justice (464 B–466 A). Sophistry gives false principles to regulate the growth and action of the soul: rhetoric pretends to cure injustice, by making the worse cause appear the better. Thus the art of the great rhetorician Gorgias sinks to the mere pretence of a quack; and thus the oratory which the Sophists generally taught, and esteemed as the essence of political art, is proved to be a mere shadow and simulacrum of the true ‘judicial’ aspect of that art. But underneath this sham of rhetoric there lie the false principles of sophistry. Rhetoric may be distinguished from sophistry; but it is close akin, and it implies the principles which sophistry teaches explicitly.1 The orator who values, and teaches others to value, mere eloquence, because it makes the worse cause appear the better, is acting on the principle, and inculcating the principle, that external success, howsoever, and by whatever means attained, is the aim and endeavour of the soul. The academic teacher of oratory, and the practical statesman who uses his oratorical powers in order to gain office, are alike mere worshippers of power. Both really believe that success is everything; both really hold that power, the consciousness of power, and the satisfaction of wielding power, are the only things that matter.

When the principle implicit in oratory has once been made clear, Plato turns to discuss its truth and its value. He leaves oratory itself in order to discuss the philosophy that lies behind oratory. Two of the persons of the dialogue are made in turn to champion that philosophy. The first of these, Polus, is ready to admit and applaud the principle that success, however it may be attained, is the thing that matters; but he has enough of conventionality left to feel himself bound to admit, that success which is bought at the price of injustice is something discreditable. The second, Callicles, is more radical; he believes that victory should go to the strongest, and the strongest should use all his strength to get victory; and he also believes that, if men will only shed their Philistinism and conventional worship of respectability, there can be no discredit attached to the ruthless pursuit of success. It is Nature’s law; and to follow Nature’s law can never be naturally discreditable, however much it may offend the proprieties of convention.

To Polus the orator is in the enviable position of the tyrant. A virtual tyrant under the form of a democratic constitution, he can sentence men to death or beggary or exile at his discretion: he can do, in a word, ‘as he likes’ (466 B–E). This leads Plato to inquire into the nature of ‘doing as one likes’, and to draw a distinction between doing as one likes (ἃ ἄν δοκῇ αὐτῷ) and achieving what one desires (ἃ βούλεται). Men do not desire the things they actually do: they desire the end or purpose for the sake of which they do those things. When they take medicine, they do not desire the taking of medicine, but the recovery of health. It is thus possible for a man to do as he likes, and yet not to achieve what he desires: it is possible for a tyrant or an orator to kill or banish, and yet to fail of attaining his desire. The argument is inspired by the view that wrongdoing is involuntary: men always desire some good, and if what they do is bad, they do not achieve what they actually desire, and in that sense their evil act is involuntary.1 But the argument does not convert Polus. He is still inclined to envy the man who can do as he likes in a State, even if, like the tyrant, he has waded through injustice to his throne. After all, he argues, to commit injustice, even if it is discreditable (αἰσχρον), does not involve any intrinsic evil or harm (κακόν) to the person who commits injustice (474 D). The reply of Plato is that injustice does involve harm, and only involves disgrace because it involves harm. The thesis which is thus raised is the thesis which also forms the staple of the Republic – whether the unjust man can ever be said to be in as good or happy a state as the just; whether stripped of all his trappings and ‘clothes’ (523 D–E), and seen, as he must be seen at the last judgement, in his inward self, he is not full of evil and misery. Injustice,2 it is argued in the Gorgias, is always miserable – never more miserable than when it goes unpunished and uncorrected; least miserable, though miserable still, when it meets with punishment and correction (472 E). Injustice is misery of the spirit, as disease is misery of the body; and it is misery because it means a diseased condition of the soul (νόσημα) in which the balance and order of health1 (τάξιζ καὶ κόσμοζ) have disappeared (504 B), and instability and disorder have usurped their place. To abide in this disease, unattended and uncured, is the crown of misery: to find an escape, through the harsh medicine of punishment, may mean misery of the body, but it also means betterment, and thereby happiness, for the soul. To punish, therefore, is to do good (ἀγαθὰ ποει ν): it is to confer a benefit (ὠϕελε

ν): it is to confer a benefit (ὠϕελε ν): and it is more – it is to do the greatest of all goods and to confer the greatest of all benefits. Money-making may free men from want of this world’s goods; medicine may free them from disease of the body; justice (δίκη) frees them from the wickedness of their hearts, and helps them most, because it rids them from the worst of all their evils. But if this be so, and if punishment be thus reformation, what shall be said of the orator, who practises his rhetoric before a court of law in order to procure escape, not from wickedness but from punishment, for those whose cause he advocates? His art is used to prevent men from receiving the benefit of punishment: it is applied for the purpose of keeping men plunged in the misery of crime. He is the enemy of mankind – or at any rate an advocate for the enemy; and they are wise who never seek to retain his services, but voluntarily go of themselves to the place where they will soonest be punished, and run to the judge as they would to a doctor, in order to prevent the disease of injustice from becoming chronic and making their souls utterly unsound and incurable (480 A).

ν): and it is more – it is to do the greatest of all goods and to confer the greatest of all benefits. Money-making may free men from want of this world’s goods; medicine may free them from disease of the body; justice (δίκη) frees them from the wickedness of their hearts, and helps them most, because it rids them from the worst of all their evils. But if this be so, and if punishment be thus reformation, what shall be said of the orator, who practises his rhetoric before a court of law in order to procure escape, not from wickedness but from punishment, for those whose cause he advocates? His art is used to prevent men from receiving the benefit of punishment: it is applied for the purpose of keeping men plunged in the misery of crime. He is the enemy of mankind – or at any rate an advocate for the enemy; and they are wise who never seek to retain his services, but voluntarily go of themselves to the place where they will soonest be punished, and run to the judge as they would to a doctor, in order to prevent the disease of injustice from becoming chronic and making their souls utterly unsound and incurable (480 A).

The culmination of the argument against Polus represents the final condemnation of rhetoric, in the narrower and specific sense of the word, as a forensic art of advocacy which makes the better cause appear the worse before a court of law, and usurps, as a sham based on mere routine, and directed to no higher end than the hearer’s gratification, the true judicial art which is based on a real knowledge of the soul and directed to its real benefit. But there is still oratory of the political order to be considered – oratory which is practised before the Assembly rather than a court of law, and seeks to direct the affairs of the State rather than to handle the causes of individuals. To consider this is really to consider not so much rhetoric as the art of sophistry – though, as we have already seen, the two are divided only by the thinnest of walls – the art which, usurping the place of the true legislative art, seeks to lay down false principles for the direction of States. Sophistry and political oratory are at bottom the same; and we must consider, and consider in their most drastic form, the principles of sophistry, if we are to understand the significance of such oratory. The veil of decency with which Polus concealed his real principles must be torn down; we must see face to face, without any concealment, the bare and naked truth.

This new stage of the argument appears with the entry of Callicles into the foreground (481 B). He is a statesman, just beginning to take part in political affairs (515 A), who speaks before the Assembly and practises oratory (500 C). He has, moreover, been educated in the principles of oratory; and fmally he is brutally frank, and eagerly ready to look at ‘things as they are’. It is his complaint against Socrates that the argument which he has just developed for the refutation of Polus rests on entire oblivion of the actual facts, and belongs to a topsy-turvy world in which all real values have undergone a process of transvaluation. If one looks at the facts, one must follow the law of Nature, and bid convention go hang. Convention is made by the majority, who are weak, and ‘make their laws, and distribute their praise and their blame, with reference to themselves and with a view to their own interests’ (483 B). Nature herself tells us ‘that it is just for the better to have more than the worse, and the stronger than the weaker’ (483 C). In ordinary life the strong are under the tyranny of the weak, like young lions charmed by the sound of the voice; but ‘a man who had natural fire enough would trample under his feet all formulas and charms and spells and laws that were contrary to Nature’s rule: the slave would revolt and become our master, and the light of natural justice would shine out of the darkness’ (484 A). This is the real truth; and Socrates will recognize it at once if only he will leave philosophy for higher things (484 C). Philosophy is all very well for youth, as a part of their education: it is of no value for grown men, or for the handling of practical affairs. Grown men must learn by hard experience the hard forces with which they have to deal: practical affairs must be handled not by the ‘knowledge’ of the philosopher, which is only a knowledge of unreal abstractions, but by direct blunt force and power.

This is the reply of Callicles to the ideas of a master-knowledge and scientific training for politics and the rest of the Socratic theory. We have already seen the genesis of Callicles’ view, and the basis which he seeks to find for that view, partly in international relations, and partly in the animal world (Supra, pp. 71–5). It remains to consider the answer which Plato makes to criticism so direct and so powerful. That answer is not only an answer to Callicles, but also a further explanation of his theory. If we accept the principle that strength is the criterion of what is right and good, Plato argues, it follows that the many, who are collectively stronger than the few, are also collectively better; and on that in turn it follows that their view, being the stronger, is also the better. But according to their view equality is better than inequality, and to suffer injustice better than to do injustice; and Callicles, on his own principle, must subscribe to these principles (488 C–489 B). To escape that necessity, he shifts his ground: for the right of strength, which, according to the previous argument, means the right of quantity, he substitutes the right of quality; and he adopts the revised formula that those who are of better quality or, in other words of greater wisdom (ϕρονιμώτεροι), should bear authority. This is a formula to which Plato has naturally no objection provided that it is understood in a Platonic, and not in an aristocratic sense, and that ‘better’ means morally better and ‘wiser’ means wiser in philosophic knowledge: provided, too, that the formula only suggests that the wiser has the right (or duty) to rule, and not the right to make profit by his rule. These provisos are expressed in a parable. If a heap of food had to be distributed, we should certainly assign the work of rationing to the person most capable; but the person most capable would be a doctor who knew something of our bodies and their needs, and it would not follow, because he had the right of distributing the food, that he received more of it himself (489 B–491 A).1 Callicles, however, objects to both provisos. When he said wiser, he explains, he not only meant wiser, but also more manly and possessed of more force of character (ἀνδρειότεροι); and when he spoke of bearing authority, he not only meant that intellectual power backed by force of character should rule, but also that it should profit by ruling. A heap of food is only a heap of food, but a State is a State; and no man will handle affairs of State unless it is worth his while and a source of personal profit.1 This in effect, Plato replies, is a gospel of hedonism. Personal profit really means personal pleasure: to make profit one’s object is to live for the sake of pleasure. Callicles is prepared to admit the inference, and willing to urge as frankly as possible the gospel of hedonism. Self-control is a virtue of no account: the best way of life is to let your appetites grow into giants, and to be wise enough, and of a strong enough courage, to satisfy those giants (491 E–492 A). Into the arguments which Plato directs against this hedonistic position we cannot here enter.2 It is sufficient for our purpose to notice that it is the principle of conduct of an orator-statesman such as Callicles, and that, in Plato’s view, all politicians, at any rate of this type, are at bottom selfish egoists.

We have seen that the orator-statesman directs his life to the pursuit of private pleasure: we have now also to see that he lives by seeking to please the multitude. At first sight a contradiction may seem to be here involved. On the one hand, we are told, the politician rules for his own advantage, and despises the interest of the community: on the other hand, it is also maintained, he uses his power to please the community (502 E). The contradiction is only apparent, and it is readily solved if we remember, first that the sovereignty of the people is a fixed limit on the politician’s freedom of action, and secondly that to please the community is not the same as to benefit the community.3 The politician who is wise in his own generation gets all the private advantage he can, subject always to the limit of popular sovereignty; and he gets it by providing his sovereign with pleasure and being rewarded accordingly. He behaves as a man might behave who made himself the tool of a despot and attained success by flattering all the worst passions of his master (510 D). The motto of Athenian public life, in Plato’s eyes, is simple: ‘We are under the people: let us flatter our masters.’ It is the motto of musician, dramatist, and statesman alike. The musician who composes for public contests is only anxious to please his audience. The dramatist, for all his solemn pretensions, pursues the same policy; he writes his plays for the gallery, and if we stripped them of all their accessories of music and rhythm and metre, we should find that they were merely contiones ad vulgum (502 D).1 The statesman follows the example of the music-hall and the theatre, and devotes himself to the role of a popular entertainer. Craving success and the inebriation of popularity, he forgets his high vocation, which is to leave his fellow-citizens better men than he found them, and to put into their hearts those most excellent gifts of balance and order, which are the only authors and begetters of justice and temperance, and indeed of all excellence and virtue (504 D: 506 D). It is not for him (if he but knew) to swim with the tide, but rather to swim against it. He must be ready to stand and to speak for the best, whether it is palatable or unpalatable: he must strive to coerce men into abandoning their loose desires, dare to ‘punish’ his country for its good, and seek to force his fellow-citizens to be free (505 B–C).

How different has been the conduct of Athenian statesmen through all Athenian history. Callicles is himself a statesman, and he has frankly expressed the principles on which Athenian statesmen have always acted. It is easy to blame the statesmen of the present; and they certainly deserve all the blame that they get. But that is far from exonerating their predecessors. ‘When the catastrophe comes’ (Plato, writing after the event, makes Socrates prophesy); ‘when the Athenians lose not only their acquisitions, but also their old possessions, they will blame Callicles, and Alcibiades, and all the statesmen of the day’; but they will forget the original culprits, in whose guilt the statesmen of that day will only be partners (519 A). The old statesmen may have been better in equipping their city with ships and walls and arsenals (517 C): they were no better in adorning it with virtue; and the original corruption of Athens goes back to Cimon, and beyond him to Themistocles, and beyond him again to Miltiades (503 B–C: 516 D–E). Even against Pericles, the greatest figure of Athenian democracy, Plato brings the same indictment (515 D–516 C). To get satisfaction for himself, he gave the people their satisfaction. To be the first man in Athens, he gave the people pay, and made them idle and cowardly, loquacious, and greedy. He made his fellow-citizens worse men instead of better, as was proved in his own person, when they turned round on him at last in a fury, because things were not going as they wished. If the shepherd of a flock (and the statesman, after all, is only the shepherd of a human flock1) had behaved in this way; if he had let his flock get so much out of hand and made it so savage by his ministrations that it turned and sought to rend him, we should not regard him as a good shepherd. Can we regard Pericles as a good shepherd? ‘We cannot point to anybody who has ever shown himself a good man in the politics of this city’ (517 A): ‘there is no single leader of a city who could possibly be unjustly condemned by the city of which he is leader’ (519 C). To Plato, in his mood of pessimism, there is no ray of light. All statesmen are shams. They are concerned, and they have always been concerned, with providing confectionery and dresses: they forget, and they have always forgotten, the need of medicine and gymnastic. They are ready to cultivate ministerial and subsidiary arts: they turn away from the magisterial and sovereign art of establishing men in full health of the soul by that right legislation, and that administration of true justice, which are to the soul what gymnastic and medicine are to the body. ‘They have filled the city with harbours and revenues:2 they have left no room for justice and temperance’ (519 A).

Such is the past of Athens: today (Plato makes Socrates say) every man who would be a statesman must ask himself whether he will be the physician of the State, who will struggle and strive to make its members as good as he can, or will be content to play the part of a servant and flatterer (521 A). Socrates has asked himself that question, and given it the only possible answer. He has sought to play the physician, and to make it his motto, ‘The people is sick: let us heal our masters’. He is one of the few Athenians – perhaps the only one – to set his hand to the true and genuine art of politics: he is the only statesman of his generation. He knows that he is sure of his reward. Having done nothing to please, and everything to improve his masters, he will be brought to trial by the false politicians he has rebuked, ‘as a physician might be tried in a court of little boys on the indictment of a confectioner’, on the charge of administering unpleasant drugs and prescribing abstinence from sweetmeats (521 D–522 E). And it will be an idle thing in that day to say, ‘I acted rightly, and I acted for your good’. The court will ignore the plea.

Yet we may suspect that from another point of view, Socrates would have been the first to disclaim the title of statesman. He may have had the right moral purpose; but professing as he did that his only knowledge was knowledge of his own ignorance, he would perhaps have denied that he had the necessary training and experience. The true statesman, Plato maintains, as his master had always maintained before him, must prove that he has been trained to the art of politics; and he must show, too, that he has practised it successfully in little things, before he seeks to practise it at all in greater things. A builder would not be chosen to build a house unless he had been trained as a builder, and could show proofs of his skill in the shape of good buildings which he had built. Surely the same is true of the statesman, and we may ask that he, too, shall have been trained in his art, and can show some proof of his skill in his work (514 A–515 A). An orator should never profess to give advice on a subject which he does not himself understand, or to meddle in the Assembly when it is a question of electing an expert to office. Such an election is the business of experts; it is architects and generals, not orators, who should give their advice when an architect or general has to be chosen (455 A–B). It is unwise to try to learn pottery while you are actually making a jar (514 D); and a statesman should have done much in a private capacity to qualify himself for office, before he ventures to assume its burden.1 We may gather, therefore, that a statesman must possess two attributes – a right moral purpose, which demands unselfishness and makes him work for the betterment of his fellow-citizens; and a full knowledge of his profession, which demands special skill and regular training. The two attributes meet and are united in the conception of government as an art, if the art is a genuine art and not a mere simulacrum. Once the conception is grasped that there is a definite art for the guidance of social life – a master knowledge whose object it is to make men know the purpose that all their activities should serve, and to make them better men thereby: once it is realized that statesmen require a definite training in this art, and everything is gained. Statesmen will cease to be amateurs and improvisers who think that any man can handle politics, and they will train themselves rigorously for their high calling: they will cease to pursue their private advantage because, being trained to an art and professing an art, they will know that it is their business to work for the good of the object of their art; and finally they will cease to try ‘to flatter their masters’, because they know that their art is a way of betterment, and not a method of flattery.

Such is the argument of the Gorgias, and so Plato seeks to prove, not only that virtue, the true political art, is teachable (as he had sought to prove in the Protagorm), but also that there is sore need of its teaching. Thus Socrates is finally justified; and thus, too, the way of future reform is indicated. Sham teaching must be overthrown, and sophistry must be refuted. Sham statesmen, who exemplify in their actions the principle of egoism which underlies such teaching, must be banished from the conduct of affairs. Knowledge must take the place of shams – genuine knowledge taught by genuine teaching; and those in whose hearts and minds it is set must guide men’s lives in its light. So we turn to the Republic, in which all these suggestions are gathered together and systematized, and the true knowledge, the true teaching, and the true statesman are all exemplified. The writings of Plato which we have as yet considered have been either negative or preparatory: in the Republic comes the positive teaching, and in it arises the building which these foundations support.

When the Gorgius was written, Plato had already present to his mind a political ideal of justice or righteousness, and he was already convinced that its attainment depended on appropriate conditions and an appropriate system of training. But an ideal may serve two purposes. It may be used as a standard of measurement and a canon of criticism, for the judgement and condemnation of existing conditions; or it may serve as a model of reformation and a hope for the future. In the Gorgias it is only the first of these two purposes which the ideal of justice is made to serve. It condemns the city of Athens; it does not point the actual way to an ideal city. Plato is clear about principles: he has not yet seen the way to put them in practice. As he says in the Seventh Epistle, he has turned aside from politics as they are: he has not yet begun to consider, as he there tells us that he soon began to do, how politics may be made, what they ought to be. He is all but convinced that the kingdom of the ideal is not of this world, and the life of philosophy is a preparation for death.1 The Gorgias may almost seem to be his apology for quietism. When Callicles laughs at philosophers who whisper in some obscure corner to a little coterie of three or four striplings (485 E) he perhaps represents Plato’s own accusation of himself: when Socrates tells Callicles that, philosopher as he is, he is yet the only statesman of his generation, he is expressing Plato’s defence of himself against his own accisation.2 But a new hope, and a more positive conception of the nature of his ideal, began to dawn. He not only conceived the plan of the Republic: he voyaged to Sicily and he founded the Academy. Philosophy, after all, was a way of life rather than a preparation for death. The rest of Plato’s life was to be devoted to the communication of that way, and to the realization of his ideal in the service of mankind.

: 161 B). The definition is not accepted, and indeed it is not really discussed. Instead of being taken in its obvious sense, that men should confine themselves to the work of their own particular capacity and station, it is twisted into the opposite sense, and interpreted to mean that each should do everything for himself, and make his own clothes and shoes and everything else that he needs (161 E). This would ascribe temperance to the Highland shepherd of whom Adam Smith wrote in the Wealth of Nations, who was ignorant of any division of labour; and Plato readily objects that a temperate State, which must, as such, be a well-ordered State, can hardly be composed of Highland shepherds (162 A). But though it is thus dismissed, the definition recurs in another form in the course of the dialogue, during the discussion of another and alternative definition. Self-control, it is now suggested, may be defined as self-knowledge (

: 161 B). The definition is not accepted, and indeed it is not really discussed. Instead of being taken in its obvious sense, that men should confine themselves to the work of their own particular capacity and station, it is twisted into the opposite sense, and interpreted to mean that each should do everything for himself, and make his own clothes and shoes and everything else that he needs (161 E). This would ascribe temperance to the Highland shepherd of whom Adam Smith wrote in the Wealth of Nations, who was ignorant of any division of labour; and Plato readily objects that a temperate State, which must, as such, be a well-ordered State, can hardly be composed of Highland shepherds (162 A). But though it is thus dismissed, the definition recurs in another form in the course of the dialogue, during the discussion of another and alternative definition. Self-control, it is now suggested, may be defined as self-knowledge ( : 165 B). If it is knowledge, Plato makes Socrates rejoin, it must, like other kinds of knowledge, be knowledge of a definite object; and what is that object? The author of the definition replies that it is threefold. Self-control is knowledge of itself; it is knowledge of all other branches of knowledge, which enables its possessor to use them temperately; finally, it is knowledge of the difference between ignorance and knowledge, in virtue of which its possessor knows the limits of his own knowledge (166 E–167 A). The reply contains elements which are genuinely Socratic and genuinely Platonic. The one knowledge which Socrates professed to possess was knowledge of his own ignorance

: 165 B). If it is knowledge, Plato makes Socrates rejoin, it must, like other kinds of knowledge, be knowledge of a definite object; and what is that object? The author of the definition replies that it is threefold. Self-control is knowledge of itself; it is knowledge of all other branches of knowledge, which enables its possessor to use them temperately; finally, it is knowledge of the difference between ignorance and knowledge, in virtue of which its possessor knows the limits of his own knowledge (166 E–167 A). The reply contains elements which are genuinely Socratic and genuinely Platonic. The one knowledge which Socrates professed to possess was knowledge of his own ignorance ). While the teacher of philosophy had thus to be vindicated against the teacher of rhetoric, the philosophical statesman had also to be vindicated against the orator statesmen of actual Athenian politics. Oratory was rooted in the constitution and life of Athens, partly in the popular law-courts, partly, and even more, in the popular Assembly. With that Assembly supreme in the State, political influence and power naturally went to the orator who could influence and control its decisions. The art of public speaking has a large scope in the representative assemblies of modern States, where the skilled debater wins his way to office on a tide of speeches; but it had a still larger scope at Athens. In a representative Assembly the orator has to satisfy the critical sense of representatives who are in constant session and constantly handling affairs themselves: in the Athenian Assembly the orator had the easiest task of charming a popular audience which, whatever its native aptitude or its political experience, was liable to value a telling speech at a very high price. The unofficial ‘leader of the people’ (

). While the teacher of philosophy had thus to be vindicated against the teacher of rhetoric, the philosophical statesman had also to be vindicated against the orator statesmen of actual Athenian politics. Oratory was rooted in the constitution and life of Athens, partly in the popular law-courts, partly, and even more, in the popular Assembly. With that Assembly supreme in the State, political influence and power naturally went to the orator who could influence and control its decisions. The art of public speaking has a large scope in the representative assemblies of modern States, where the skilled debater wins his way to office on a tide of speeches; but it had a still larger scope at Athens. In a representative Assembly the orator has to satisfy the critical sense of representatives who are in constant session and constantly handling affairs themselves: in the Athenian Assembly the orator had the easiest task of charming a popular audience which, whatever its native aptitude or its political experience, was liable to value a telling speech at a very high price. The unofficial ‘leader of the people’ ( ) depended for his position on the command which he exercised over the Assembly; and Pericles himself, though he held the official position of στρατηγοζ, owed much of his actual influence to his oratory, and to the fact that ‘alone of the orators, he left his sting in his hearers’. In the Euthydemus, and again in the Politicus, Plato recognizes the orator as a serious rival to the true statesmen, and is at pains to distinguish them from one another. It is natural that he should devote, as he does in the Gorgias, a separate dialogue to the subject of oratory, and to the discussion of its basic principles and its real value. It is natural, too, that the view which he takes of oratory in that dialogue should be severely unfavourable, and that, writing of Athenian institutions from this angle, he should condemn them much more drastically than he does in the Meno or the Protagoras.

) depended for his position on the command which he exercised over the Assembly; and Pericles himself, though he held the official position of στρατηγοζ, owed much of his actual influence to his oratory, and to the fact that ‘alone of the orators, he left his sting in his hearers’. In the Euthydemus, and again in the Politicus, Plato recognizes the orator as a serious rival to the true statesmen, and is at pains to distinguish them from one another. It is natural that he should devote, as he does in the Gorgias, a separate dialogue to the subject of oratory, and to the discussion of its basic principles and its real value. It is natural, too, that the view which he takes of oratory in that dialogue should be severely unfavourable, and that, writing of Athenian institutions from this angle, he should condemn them much more drastically than he does in the Meno or the Protagoras. ν): it is to confer a benefit (ὠϕελε

ν): it is to confer a benefit (ὠϕελε (292 D). The knowledge the statesman must produce in his State is thus a knowledge of one thing – the final purpose to be served by each action.

(292 D). The knowledge the statesman must produce in his State is thus a knowledge of one thing – the final purpose to be served by each action. Ethics, 1103, a 32–3). This is a principle of profound significance, which justifies, for instance, the extension of the suffrage to classes who do not know how to use it until they have actually used it.

Ethics, 1103, a 32–3). This is a principle of profound significance, which justifies, for instance, the extension of the suffrage to classes who do not know how to use it until they have actually used it. ις. He has in mind, it is true, orators of the stamp of Isocrates, who are half-way houses between the philosopher and the politician; but the question he raises has also a wider application.

ις. He has in mind, it is true, orators of the stamp of Isocrates, who are half-way houses between the philosopher and the politician; but the question he raises has also a wider application.