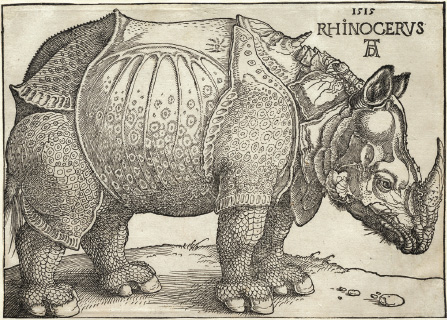

7. Albrecht Dürer's famous 1515 woodcut of Ganda the Indian rhinoceros provided the conventional European image of the species right until the arrival of live rhinoceroses in the eighteenth century.

If the story of a global phenomenon can ever truly be said to have a single point of origin, then for the Age of Discovery that site would be Lisbon. There are many reasons why it is the faces of Portuguese traders – rather than Spanish, French, Dutch or English – that can be seen on the Benin Bronzes and ivories. First, there were geographical factors that help explain why the Portuguese became the great mariners of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Portugal’s coastline faces not the safe, well-charted waters of the Mediterranean but the apparently endless and forbidding expanses of the Atlantic. This orientation almost urged Portugal’s mariners out into the deep ocean, and encouraged its kings to speculate as to what riches and trades might be found beyond, if the great distances could be crossed.

Technological advances in the sixteenth century, in the mariner’s craft and in the sciences of navigation and cartography, all assisted the Portuguese in mastering the art of long-distance travel. One critical development was provided by the shipwrights of Lisbon. Through ingenuity, and trial and error, they designed a vessel ideally suited to long-distance trade and exploration: the small, highly manouverable caravel. And more prosaically, an important reason why it was Portugal, rather than one of her wealthier, more powerful competitors, who came to dominate the age's seafaring: Portugal needed money. The kings of this small realm were so poor they were unable to mint their own coinage, and Portugal was rightfully wary of the burgeoning power of neighbouring Spain, recently united by the royal marriage of Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile in 1469. Thus the compelling dream of trading for gold in Africa, or navigating around Africa and trading for spices with the peoples of India, animated successive generations of Portuguese explorers.

Portugal’s first foothold on the African coast was the city of Ceuta, now an autonomous city of Spain. From there the caravels inched along the north African coast. Expedition after expedition, each ventured a little further south, then east. By the 1430s the Portuguese had managed to pass Cape Bojador, a headland beyond which, it had been believed, no ship could find winds to return to Europe. Later that same decade they reached the Bay of Arguin in what is now Mauretania. By the 1460s they had reached the coastline of west Africa and erected a fort, the oldest European building in Africa. From that bridgehead they were able to tap into the flow of Africa’s gold at source. That one trading post, the fortress of Saõ Jorge da Mina, doubled the income of the monarchy. Little wonder that in 1580 the kings of Portugal added the title ‘Lords of Guinea’ to their growing list of royal titles and honorifics. The wealth of Saõ Jorge da Mina helped fund further expeditions, and by 1498 their ships reached India, and in 1500 they discovered Brazil.

The factors that had made all this possible were not products of European thinking but innovations born of the synthesis of knowledge and technologies. The Age of Discovery famously brought about a flurry of cultural fusion; less well understood is that it was itself only made possible by a similar coming together of ideas. Many of the advances in cartography and astronomy that made it possible for the earliest expeditions to cross featureless seas had been pioneered by Iberian Jewish mapmakers, who drafted the charts that these expeditions relied on. Added into this mix were Genoese financiers and bankers who helped organise the building of ships and the victualling of expeditions. The mariners who led those missions also adopted new navigational knowledge gleaned from Islamic sailors.

When Vasco da Gama reached India in 1498, his great feat of navigation had, in its final stages, been achieved with the assistance of an Arab navigator. Hired at the port of Malindi, on the coast of modern Kenya, this unknown Arab mariner used the stars and his charts of the Indian coast to guide da Gama to Calicut two months later, having harnessed the monsoon winds. Port side in Calicut, da Gama, on this auspicious and long-dreamed-of moment, was met not by an Indian delegation but by an Islamic merchant from Tunisia who cursed them in Spanish for having broken into a trade previously dominated by Arabs and north Africans.1 The Portuguese were late. The first age of globalisation had been under way in Asia long before Europeans began to stake their claims.

Contact with and exploration of the distant lands beyond Europe transformed the economy and culture of Portugal from the second half of the fifteenth century onwards. Long-distance trade, the wealth it garnered and the new worldliness it conveyed upon the people of Portugal, and Lisbon in particular, changed not just their economy but also the way the Portuguese viewed themselves. Around 1515 the Portuguese built the Tower of Belém, which still stands guard over Lisbon harbour. It was erected to celebrate the nation’s new discoveries and her growing wealth, and in acknowledgement of the centrality of overseas trade to the Portuguese economy. Within the stonework of the tower was set a carving of an Indian rhinoceros. As any sixteenth-century visitor to Lisbon would have known, the carving was not merely an image of what a rhinoceros might look like, based on travellers’ tales or amateurish drawings: the depiction was derived directly from experience and was of a specific creature.

Despite 500 years of weathering and erosion, the rhinoceros can still be made out at the base of the tower on the landward side. It shows an animal that arrived in Lisbon in 1515. The creature in question had originally been a diplomatic gift to Afonso de Albuquerque, governor of the Portuguese trading posts in Goa, from Muzaffar Shah II, the Sultan of Gujarat. But Albuquerque passed the rhinoceros on to his monarch, King Manuel I ‘The Fortunate’. On 20 May 1515, after 120 days at sea, the poor animal, known by his Gujarati name of Ganda, finally landed at the docks near the Tower of Belém, then still under construction. Although rhinoceroses and other exotic animals had been brought to Europe during the Roman empire, the creature that landed in Lisbon harbour was the first of its species to have been brought alive to Europe since the fall of Rome, and in the intervening millennium such beasts had become almost mythical in the minds of isolated Europeans. As all that was known of these animals in Europe came from the writings of ancient authorities, the Portuguese court turned to Pliny the Elder’s discussion of the nature of the rhinoceros for information on their habits. Thus in June 1515 King Manuel had the recently arrived rhinoceros fight a young Indian elephant that was already in his menagerie, in order to test Pliny’s assertion that the rhinoceros and the elephant were natural and eternal enemies. The rhinoceros is said to have won on the grounds that the elephant fled the field of combat before any fighting had actually taken place.

The arrival of an Indian rhinoceros – enormous, alive and animated – astonished the people of Lisbon, and its fame spread rapidly beyond the borders of Portugal. So quickly did the creature’s celebrity spread that within a few months a simple woodcut print by Giovanni Giacomo Penni had appeared in Rome. Shortly afterwards the German artist Hans Burgkmair produced a far more elaborate and anatomically accurate woodcut print, showing the animal with ropes around its feet. However, it was not until news of the animal’s presence in Lisbon reached the German city of Nuremberg that its fame was permanently imprinted on the European memory, becoming not only a symbol of Portugal’s global reach but also representing the new age of knowledge and discovery, through the work of one of the greatest artists of the sixteenth century.

Albrecht Dürer never saw Ganda with his own eyes; instead, he relied on a sketch produced or acquired by Valentim Fernandes, a German printer resident in Lisbon.2 The Fernandes sketch was sent to Nuremberg, and from that Dürer produced his famous woodcut print of the rhinoceros that was replicated and sold thousands of times over. The woodcut print was fine art’s equivalent of the Gutenberg press: a revolutionary technology that made the previously unaffordable suddenly accessible. Thanks to the artist’s prodigious talents, and the medium he employed, Dürer’s vision of Ganda the rhinoceros entered into the imaginations of vast numbers of people. ‘No [other] animal picture,’ claims one historian, ‘has exerted such a profound influence on the arts.’3

While Dürer ensured that the image of Ganda lived on, the creature itself sadly did not. In December 1515 Dom Manuel dispatched Ganda to Rome as a gift to Pope Leo X, who was already the proud owner of an albino Indian elephant. The animal never arrived. The ship carrying the unfortunate beast encountered a storm in the Mediterranean and foundered off the Italian coast. As Ganda was chained and shackled to the deck, he drowned, and never became part of the Medici Pope’s menagerie.4

While the arrival of exotic beasts caught the attention of Europe’s educated elite, and fired both the artistic eye and entrepreneurial imagination of Albrecht Dürer, visitors to Lisbon around the same period were just as astonished by the diversity of human life they found in the city. By the latter decades of the sixteenth century Lisbon had gone from being a backwater on the edge of Europe to becoming the most diverse and global trading city on the continent. And increasingly Lisbon looked the part. Not only were the goods and spices of Africa and Asia flowing into the city’s broad harbour; so, too, were people from across Portugal’s constellation of trading partners and trading bases. In the second half of the century Lisbon was home to a large population of Africans, as well as an unknown number of people of mixed heritage. Together they may have made up around 10 per cent of the city’s population.5 During a visit of 1582, Philip II of Spain commented, in a letter to his daughters, that he had seen black dancers on the streets of the Portuguese capital from his window.6

Were it not for the devastating earthquake and tsunami of 1755, which all but destroyed the Renaissance city, the evidence of the diversity of sixteenth-century Lisbon would be enormous. That disaster, which razed much of the old city and cost thousands of lives, also obliterated the official records of the Portuguese state and much of the material culture of Lisbon.

Only a handful of paintings of the cityscape survive; among the most stunning is an incredible panoramic painting of the Chafariz d’el Rey, (The King’s Fountain), which once stood in the Alfama district, near the River Tagus. It was painted by an anonymous artist, probably from the Netherlands, some time between 1570 and 1580. What is most striking to the modern viewer is that among the many figures within this bustling urban scene are a great number of Africans. Another surviving painting of the Rua Nova dos Mercadores, again anonymous but probably painted in the period 1570–1619, shows black Lisboeta (residents of the city) of various social classes going about their daily affairs. Around half of the figures in that work are African.

In The King’s Fountain the ornate public fountain of the painting’s title is at the centre of the narrative action. Coming to and from the fountain are aguaderos, water carriers. These black Lisboeta were almost certainly slaves, carrying heavy jars of water back to the homes of their masters, many bearing their load upon their heads, west African style. A formal slave trade had begun between Portugal and west Africa in the mid-fifteenth century, but slavery was an older, pre-established institution, and there were white slaves as well as black in Renaissance Portugal, just as there were across other parts of Europe at the time. Furthermore, the records suggest that there were men and women living in states of slavery in late sixteenth-century Lisbon whose ancestry lay not just in Africa but also in India, Brazil, China and Japan.7 Slavery and blackness were not yet ubiquitous in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries – that was to come later. Also, as manumission was common, a number of the black figures in any street scene from the period could have included black freemen and women, as well as those still in bondage. This may well be the case for some of the other African figures in The King’s Fountain, such as the ferrymen and street traders. Perhaps the most striking black figure shown is a knight of the Order of Santiago, who appears on his horse with a sword, cloak and other finery. Records from the time confirm that three African men with connections to the court did gain entry into this exclusive order, and the sight of comparatively wealthy and educated Africans on the streets of the Portuguese capital was not uncommon. Among the Africans known to be resident in Lisbon during this period were ambassadors, young aristocrats and even princes from the African societies that had become Portugal’s trading partners. The kings of the west African kingdom of Kongo, for example, dispatched younger male relatives to Portugal to be educated in European languages and the Catholic faith.8

8. In The King’s Fountain Portugal’s links to her African trading partners are made clear by the number of Africans, of all social classes, from slaves to a knight on horseback, who appear on the streets of Lisbon's Alfama district.

The strength of the ties between Portugal and her African trading partners can also be seen in the African art that made its way to Lisbon and in the African products depicted as details within Portuguese paintings. Again, such works that exist today – which range from rudimentary trinkets picked up by sailors as objects of curiosity to priceless works of staggering craftsmanship – are rare survivors of the calamity that befell Lisbon in 1755. We would know far more about them, their origins and their place within Portuguese society had the Casa da Guiné – which held the records of Portugal’s trade with Africa – not been obliterated by this almost biblical catastrophe.9

Among the more valuable and intricate works of art are those that were dispatched to Lisbon as diplomatic gifts from the kings of Benin, Kongo and the region that is today Sierra Leone. The most exquisite of those works that have survived tend to be carvings in ivory, produced to exceptionally high standards by skilled craftsmen. Benin ivory, both in its raw state and worked by such artists, was one of the artistic products offered in exchange for brass manillas and other European goods. As the work generated by Benin’s guild of metalworkers was exclusively reserved for the court of the Oba, and the export of brass plaques, heads and statues explicitly prohibited, ivory carvings were luxury items that the craftsmen of the Edo people were able to produce for European customers. The prohibition against the export of brass partially explains why the astonishing technical quality and artistic flair of the Benin Bronzes came as such a shock to the art establishment and public of late Victorian Britain.

Benin’s ivory-carvers, along with those of Kongo and Sierra Leone, appear to have regarded the new globalism of their age as a business opportunity. To maximise profits, they began to diversify and produce carved ivory objects specifically designed for export to Portugal. These works of art in African ivory were created by skilled craftsmen who had never set foot in Europe but who were able deliberately to reflect European tastes. The carved figures that appear in salt cellars from the period are European not Africans, as their clothes and facial features demonstrate. They wear Christian crosses and have long beards. The designs of these ivory goods appear to have been copied from illustrations brought to Africa by the Portuguese themselves. Some west African craftsmen were so well attuned to the tastes and culture of their Portuguese customers that they incorporated Portuguese symbols and insignia into their designs. Ivory horns, known as oliphants, from sixteenth-century Benin and Sierra Leone were often engraved with the coat of arms of the Portuguese royalty, the House of Aviz.

Among the many Renaissance Europeans who owned works of art and craft created by Africans was Albrecht Dürer, a man endlessly enthused by the growing understanding of the world that was a hallmark of his era. Well travelled within Europe and personally committed to re-imagining what the role of the artist might be, Dürer was magnetically drawn to the visual imagery of other cultures. He may not have visited Ganda the rhinoceros in Lisbon himself, but he did possess goods that might well have been brought into Europe via the Portuguese capital. Among the artefacts known to have been owned by Dürer were a number of ivory salt cellars, which, although now lost, are believed to have been made by highly skilled guilds of ivory-carvers from Sierra Leone.10 It seems possible that Dürer may have bought these objects on a trip to Antwerp in 1519.

9. An intricate and wonderfully playful ivory salt cellar: made by Benin craftsmen but depicting Europeans and the sailing ships that made trade between Europe and west Africa possible.