Motivations for technological progress - private versus public funding

“Every hour a scientist spends trying to raise funds is an hour lost from important thought and research.”

— Isaac Asimov

Anyone interested in research and particularly research with high impact, is at some stage likely to consider the question of what funding mechanism produces the best outcomes. One of the first questions to be asked is which tends to be more productive: private or public funding? After studying the subject of impact, it is hard not to come to the conclusion that in recent years most impact has been generated by private companies rather than publicly-funded organisations. Consider, for example, modern personal computers (PCs). The majority of commonly utilised hardware and software for PCs has been generated, standardised, and made popular by private companies, nearly all of which are based in the USA (e.g. IBM and Microsoft). So why is the private sector so dominant? The reason is perhaps associated with the nature of private companies and in particular their structure and patterns of operations. A private company is, essentially, a group of (often very talented) private individuals who have effectively clubbed together with the aim of doing something well; so well that they hope to make money and, if possible, achieve long-term dominance in their chosen area (something that, for example, Microsoft has dramatically demonstrated for the sector of office and home software). In order to do this, they have to work hard; they need to apply an intensive effort, meet goals and deadlines and be highly efficient in their operations. To increase productivity, they have avoided many of the distractions that most of today’s organisations often seem to be obsessed with; an example is political correctness (or at least they used to be able to avoid it). So, what is the situation in the public sector? We have to be honest and say that there is less pressure to be efficient and highly productive – which is undoubtedly due to the lack of a pressing need to ‘get the product out the door’. Whereas

private companies always seem to want something done yesterday, an organisation such as a university will be looking towards the next semester – which is likely to be in several months’ time. Regarding political correctness, while private companies do not generally have the time to indulge the subtler aspects of PC culture (at least in most of their internal operations), public organisations such as universities and the dear old BBC are, as was observed previously, pretty much obsessed with PC issues. By the time public bodies such as universities have completed their PC self-flagellations, they hardly have any time or energy left for undertaking productive research. The other important factor is, of course, competition. Where there is very strong competition, technological progress is often markedly pronounced. Perhaps the most intense form of competition is that of a total war between powerful nations. If countries fear for their survival in such a war then the effect is even more intense, and a good example of a conflict where this occurred is World War Two (WWII). As most people know, in the summer of 1940 Britain did fear for its survival. Nazi Germany had invaded nearly all of Europe, had an air force twice the size of the RAF and was planning an invasion of merry olde England (Operation Sea Lion

). About the only thing that would make Britain safe would be a victory by the RAF over the Luftwaffe. And so, what happened? Sure enough, the British put enormous amounts of ingenuity and effort into invention and development of a radio-based early warning system all around the south and east coast that would detect enemy aircraft many miles away (giving both direction, range, and number of aircraft). This new system was known as RDF - Radio Direction Finding

(later designated as Radio Detection and Ranging

or RADAR). This meant that the RAF were ready for the invading planes and could often intercept them well before they reached English soil.

The result was that RADAR (along with critical and breath-taking bravery and dedication to duty from the Hurricane and Spitfire pilots and support staff) enabled the RAF to win the Battle of Britain. A small country on the western edge of Europe had halted the apparently insurmountable wave of conquest of an aggressive, efficient, powerful, and politically anachronistic Nazi Germany

(which modelled itself on the Roman Empire - 2000 years after the fall of the latter). The consequences of this first blow for freedom by Britain, for the future progress of WWII and hence the future destiny of the civilised world, can hardly be overestimated. And what of German technological progress in WWII? I think you would have to call it impressive, in fact, very impressive (in stark contrast to their politics of the time). Consider, for example, the Panzer Tank, or the Messerschmitt Me 262 (the world's first operational jet-powered fighter aircraft), or (most amazingly) Hitler’s ‘vengeance’ weapons – in particular the V2 rocket. These three instruments of war were developed in chronological order as the war progressed. When it started to look as though the Axis was losing, Germany naturally started to fear for its survival and so the technological inventiveness and rates of development became correspondingly accelerated.

A Supermarine Spitfire; the Battle of Britain was a pivotal moment in WWII and one of the most significant parts of Britain’s long history. (Pen and ink drawing by the author.)

The V2 rocket is indeed a technological marvel and was so technologically advanced that the Allies were studying and launching them years after the war ended. Hitler launched V2s (and V1s) to exact vengeance on the UK for the heavy bombing of Germany by the Allies towards the end of WWII (which was actually quite catastrophic for the German cities and civilians). What he was really trying to do was to terrorise the British public with these weapons. To be honest, a V2 hurtling towards you is indeed quite a terrifying prospect, since it was the first weapon to have the dubious characteristic of being able to kill you without you even realising it was approaching, travelling as it does at velocities greater than that of sound (which is something that also made them extremely difficult to shoot down). A V2 loaded with 1000kg of high explosive is certainly something that could terrify and also kill quite a number of people, but it is not a weapon that could win a world war (at least not when manufactured in the limited quantities that Germany could manage towards the end of WWII). Nevertheless, V2s loaded with nuclear warheads do represent a weapon that could have enabled the Nazis to capture the world, even in conditions of limited production. Chillingly, during the war the Germans were working on a nuclear weapons project (with heavy water production via hydroelectric plants in Norway) and the world owes a debt of gratitude to the Norwegian commandos and Allied bombers who sabotaged these operations.

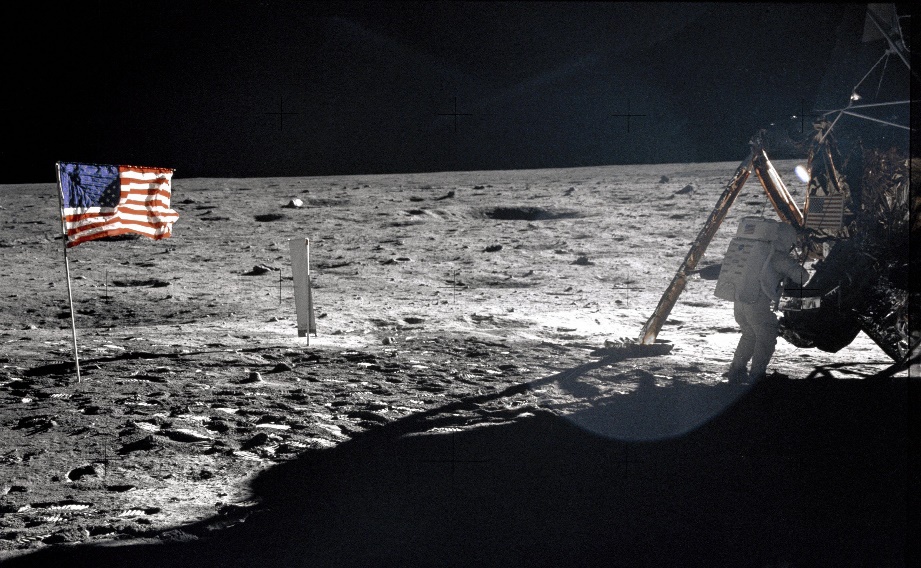

After the war, America employed the V2 creator, Wernher von Braun, as the chief architect of the Saturn V super heavy-lift launch vehicle that propelled the Apollo spacecraft to the Moon. Speaking of the Apollo project, it was again competition that spurred this project on – specifically competition with the Soviet Union to be the first to land a man on the moon. I think that anyone who is a baby boomer and who has any kind of interest in science/technology feels the enormous influence on their childhood learning and experience that Apollo and the Saturn V rocket had (or at least it had on me). I can remember seeing Neil Armstrong making his ‘enormous leap for mankind’ and I still have the science encyclopaedias that my parents bought my brother and myself for Christmas – which featured

articles on the great Saturn V rocket.

Apollo 11 mission commander Neil Armstrong on the lunar surface in 1969. (Photograph courtesy of NASA.)

By the way, if the Nazis had won the war it would almost have certainly led to widespread and on-going political unrest and continued fighting, to such an extent that it is very unlikely that manned space flight would have been developed or a moon shot undertaken. In fact, it would have led to such chaos that I am not sure that much in the way of electronics technology such as personal computers would have been developed – so I would not be here now enjoying the luxury of gently tapping keys on my PC. Such reflections lead me to think of the famous gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson - specifically his comments in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas

on the Circus Circus casino in Las Vegas: “The Circus Circus is what the whole hep world would be doing Saturday night if the Nazis had won the war. This is the sixth Reich. The ground floor is full of gambling tables, like all the other casinos ... but the place is about four stories high, in the style of a circus tent, and all manner of strange County Fair/Polish Carnival madness is going on up in this space.”

A typical Las Vegas street scene - the Circus Circus is by no means the most outlandish or surreal hotel/casino in town. (Photograph by the author.)

There does not, however, have to be a war raging or space race in full swing, for us to be able to see the benefits of competition. Consider, for example, how good the operations are of the four major UK grocery retailers: Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda, and Morrisons. Long gone are the days of the old rogue food outlets that used to adulterate food with the consequent need for the trusty old Cooperative Retail Society to give us good food at an honest price. In fact, the big four are so efficient that the Co-op has a job competing with them – but the good old Co-op still, in many communities, provides a local shopping experience and community feel – which is invaluable for those who are unable, or who cannot afford, to drive.

So the British are very good at shops and selling (Napoleon did, after all, call us a ‘nation of shopkeepers’ – he meant it as an insult but I believe it was largely taken as a complement!), but are they equally good at, for example, secondary education? To judge by the crises

that seem to regularly engulf schools around the country, perhaps not. If so, has the reason to do with the fact that state education is not something for which it is very easy to introduce competition? And what about healthcare in the UK?

I, like many people, love the NHS and consider it a cornerstone of British culture. There is something tremendously civilised about the concept of everyone paying into a fund that provides help to fellow citizens when they fall ill and, critically, provides it on the basis of clinical need rather than the ability to pay. This is a great thing, and it needs to be maintained and continuously enshrined in our culture. However, in my view, this does not mean that the NHS cannot make use of provision from the private sector to care for or treat some of its patients. Although I have not, thank God, suffered much ill health or needed much medical treatment, I have occasionally had treatments on the NHS and on one such occasion at a private hospital near Bath. I was very impressed with the whole experience and believe that such quality experiences should be available to other NHS patients. Also, while maintaining and funding the NHS, something does need to be done to tackle organisational cultures that result in poor quality food, dreary hospital buildings, and interiors which, I believe, without the effects of some injection of new thinking and competition, would forever remain sub-standard, no matter how much funding were applied.

So much for NHS practice; but what about NHS research and technological developments? Unfortunately, despite high levels of funding (£billions per year) these are often, particularly outside of London and the ‘Golden Triangle’ (Cambridge, Oxford, and London), relatively limited in terms of their accomplishments and impact. There are many reasons for this – one is undoubtedly the effects of lack of competition in public sector organisations – but another has to do with the way clinical careers are structured within the NHS. Put simply, there are insufficient incentives for leading clinicians, particularly those with extensive/demanding practices, to undertake research. Or, to express it another way, leading NHS surgeons or senior clinicians are often so busy with their medical practices, i.e. treating patients in need in the NHS, that they simply

do not have time for research. This can limit research outcomes/impact since, from personal experience, I can confirm that it is impractical to undertake research and development of medical devices without the close involvement of clinicians.

Another circumstance that the NHS finds itself in is that of extreme conservativism, perhaps resulting from the natural and understandable conservatism of the medical profession, as well as the tendency of British public institutions to be inward looking and relatively resistant to change (a good example being the BBC). This can result in slower adoption of improved procedures and/or devices than would be desirable. Therefore, no matter how much funding is available, as long as the proportions of NHS clinicians who cannot (or do not wish to) undertake research remain at their current levels, it will be difficult for the NHS to attain the levels of research with impact that would perhaps be expected of so substantial and admirable an organisation

.