3

Innovating Privacy

The polarizing nature of digital redemption is due in part to its odd relationship to privacy, a polarizing subject in and of itself. The particular issues raised by the right to be forgotten are difficult to understand as privacy issues because they are about information that has been properly disclosed but has become or remained problematic. Conceptualizing privacy is perhaps as endless a task as keeping track of the ways in which technology challenges it, but new theories focused on the new information landscape have opened up possibilities for reconceptualizing what privacy can mean in the digital world. The right to be forgotten may be one of those possibilities, but the particular issues raised by the right are also difficult to understand as manageable issues. Like privacy, the right to be forgotten can mean too many things that need to be sorted and organized in order to move forward.

To some people, access to old personal information may be a privacy violation or form of injustice—but not to others. Privacy today is most often discussed in terms of a liberal political philosophy that understands society as a collection of somewhat autonomous individuals with stark differences in interests and priorities regarding what boundaries they maintain. Under a liberal notion of privacy, the protection of these differences in boundary management serves to support the goals of civil society. Privacy has been summarized by Alan Westin as “the claim of individuals, groups, or institutions to determine for themselves when, how, and to what extent information about them is communicated to others.”1 His focus on control is different from Samuel Warren and Louis Brandeis’s “right to be let alone,”2 developed only decades before, but neither seems easy to achieve in the twenty-first century. Fortunately, a number of theories have been developed since to meet the demands of a changing socio-technical landscape.

Information privacy is an evolving concept.3 In 1928, Justice Brandeis called privacy “the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men.”4 Seventy-one years later, Scott McNealy, the CEO of Sun Microsystems, declared, “You have zero privacy anyway. Get over it.”5 The juxtaposition of these quotes represents the current state of privacy. Technological change has seemingly shaken up society and privacy along with it, but not for the first time.

In 1966, Westin wrote, “The very novelty of [the development and use of new surveillance devices and processes by public and private authorities] has allowed them, thus far, to escape many of the traditional legal and social controls which protected privacy in the pre–World War II era.”6 He was referring to a slew of “new” technologies: the radio transmitter microphones that allow conversations to be overheard without the consent of both parties to a conversation (phone tapping), a “radio pill” that emits a signal from within the body, secret “miniature still and movie cameras with automatic light meters” that can be triggered by movement (motion-detection cameras), long-range photography equipment and closed-circuit television units the size of a cigarette pack, beepers smaller than a quarter that transmit a signal for several city blocks, audial surveillance that can be built into one’s attire, photochromic microimages, computer storage and processing, credit and debit card systems, polygraphs, and personality tests.7 New ways to capture and communicate information about more aspects of life from novel places and sources test our notions of and protections for privacy.

Three categories of technological advancement have bent these notions out of shape once again. The Internet allows for instant, cheap, and widespread publication of and access to information. The collection of information through computer code captures our attributes and movements through the network, sensors capture our attributes and movements outside the network, and numerous recording devices (from the personally wearable to the static, publicly situated) capture glimpses of us as we move throughout both realms. The storage, aggregation, and processing of all this information is organized and analyzed to provide utility and efficiency. Together these technological advancements have contributed to incredible social shifts in the way information is created, shared, and understood, leaving overwhelming informational vulnerabilities.

Recent informational threats seem to come from everywhere at all times but can be organized into four categories: threat of limited foresight, threat of rational ignorance, threat of others, and threat of others like us. The right to be forgotten is an attempt to address these threats. It assumes that information will be leaked, collected, shared, and analyzed by individuals and about individuals and seeks to limit the impact by protecting individuals through digital redemption, which incorporates values associated with and the vulnerability of identity, reputation, autonomy, and privacy.

As the Jezebel example in the introduction exemplifies, two important questions for the many countries considering a right to be forgotten are how long consequences should last and why. How should information we actively create and intend to share be assessed and addressed? Thus, the first threat to our digital records comes from our own actions. The social media scholar and youth researcher danah boyd explains, “In unmediated spaces, structural boundaries are assessed to determine who is in the audience and who is not. . . . In mediated spaces, there are no structures to limit the audience; search collapses all virtual walls.”8 The intended or expected audience is not always the actual audience. The teens in the Jezebel case were probably not expecting the site to read their tweets. They also probably did not expect the tweets to be used by Jezebel in a way that could jeopardize their futures.

Adults and experts are also susceptible to limited foresight in the Digital Age. No matter how much one knows, it can be incredibly difficult to foresee the impact of shared data. The pseudonymous author “George Doe” recounted his family’s experience with 23andMe, a service that has offered genetic testing since 2007, in an article titled “With Genetic Testing, I Gave My Parents the Gift of Divorce.”9 23andMe does more than provide genetic reports and raw genetic data; it connects users who have opted to participate in the “close relatives finder program,” which suggests similar genetic history and possible common ancestry.10 Through the service, George Doe learned that he had a half brother, a discovery that threw his family into upheaval. George Doe is not a child fumbling around a complex social networking site or an adult oblivious to the field of bioinformatics; he is a stem cell and reproductive biologist with a doctorate in cell and molecular biology.

We also passively create potentially regrettable information passively as we spend time as networked individuals. Little lines of code are created to note, measure, and categorize our computationally perceived movements, interests, and characteristics. These digital footprints are meant to be read, aggregated, and analyzed by machines, which makes them hard for users to understand and manage. Processing and use are detailed in long and difficult-to-decipher terms of service. Digital footprints are rarely disclosed to the public, but even when they are disclosed anonymously, a surprisingly small amount of combined information can lead to reidentification of the persons belonging to those footprints.11 Moreover, the results of processed digital footprints are often presented to the user in the form of predicted content, like an advertisement or news story that is likely of interest. In 2007, the Facebook user Sean Lane bought an engagement ring for his girlfriend online without knowing about or understanding the agreement between the site and Facebook. He was horrified to find the headline “Sean Lane bought 14k White Gold 1/5 ct Diamond Eternity Flower Ring from overstock.com” presented in his Facebook newsfeed to all of his friends, coworkers, and acquaintances and, of course, his girlfriend.12 “Thus, the decision not to protect oneself paradoxically may be considered as a rational way to react to these uncertainties: the ‘discrepancies’ between privacy attitudes and privacy behavior may reflect what could at most be called a ‘rational ignorance,’” explains the privacy economist Alessandro Acquisti and the information scientist Jens Grossklags.13 The difficulties in calculating risk, exercising choice, and initiating control over so much personal data (in combination with the novel uses of old information, creating an incentive to keep all information)14 have led some observers to argue for a right to be forgotten as an effective way to enforce user participation in data-protection regimes.

The other threats come from what other people do. People have posted some pretty bad stuff about other people on the Internet. Daniel Solove’s Future of Reputation is chock full of examples of people taking to the Internet to express their disdain for others. An ethically interesting (and PG) example occurred when an everyday breakup between two noncelebrities in Burger King was live tweeted by a stranger, complete with photos and video. The eavesdropping prompted an article in Cosmopolitan to warn, “Let this be a lesson to all of you airing your (very) dirty laundry in a public place. You never know who’s nearby and ready to broadcast your life to the interwebs.”15 The threat of others is hard to ignore. Content may seem harmless or mundane, or it may be clearly malicious or spiteful; but all can cause real problems down the line. Being at the mercy of strangers, friends, and enemies will cause most of us to be hyperaware and fall in line—or so the chilling-effects argument goes.

Predictive analytics often fill in the blanks we leave in our data trails. These are not characteristics that are expressed or collected through our actions but holes in our digital dossiers that get filled on the basis of the characteristics of others like us. At age eight, a kid named Mikey Hicks found himself on the Transportation Security Administration selectee list that subjects him to higher security scrutiny when he travels. His father, who has the same name, was also on the list. No one was clear as to why they were on the list, and the family was told it would take years to get off the list; but it was likely the actions of a third Mike Hicks were to blame. Netflix will recommend a musical because people who watched some combination of other films and television shows like musicals. Target might label me, as it has others,16 as pregnant (to the precise trimester, in fact) if I buy a certain set of products because so often women who buy that set of products are pregnant. We are not only at the mercy of our own pasts; we are at the mercy of pasts of others who are like us. How can we charge anyone with guarding against machine inferences made about us on the basis of the data of others? This is, therefore, a more technical question than any of the others, and this threat will be intertwined with broader debates about big data. How can you find and understand, let alone delete, data created about you on the basis of the history of others?

There are a number of ways that the concept of privacy has broken down in light of these shifts and vulnerabilities and reasons why it is being reconceptualized. Central to this breakdown is the “privacy paradox,” which describes the apparent inconsistency between Internet users’ actions and feelings about privacy.17 Most claim to care about protecting information and to value personal data but do not take steps that reflect these values and give away their data freely. In a paper and analog world, consent could more easily be granted for a more manageable amount of data after notice has been given regarding the terms of data collection and use. Individuals were more in control and aware of the personal data they disclosed—a sentiment that each generation seems to longingly hold about those prior.

Today, the information landscape places an extraordinary and unrealistic burden on the user. Lorrie Faith Cranor and Aleecia McDonald determined that it would take seventy-six work days to read the privacy policies users encounter in a year.18 Relying on privacy policies as a form of notice is ineffective because of what Helen Nissenbaum calls the “transparency paradox”: if data controllers accurately and comprehensibly describe data practices, the policy will be too long and complicated to expect a user to read it.19 Users exercise rational ignorance when they do not diligently protect their data.20 Trading small pieces of data for a service may lead to harms, but these harms are abstract and stretched over time, making them difficult to calculate. The promised convenience, however, is concrete, immediate, and very easy to calculate. Weighing trade-offs within a structure of so many entities collecting, using, and trading data at new, technically sophisticated levels is simply too much to ask.

Additionally, relying on individual choice may not promote the social values that make privacy a core concept of liberal society. Robert Post argued in 1989 that privacy “safeguards rules of civility that in some significant measure constitute both individuals and community.”21 A few years later, Priscilla Regan argued that the lesson of the 1980s and early 1990s was that privacy loses under a cost-benefit analysis when weighed against government-agency needs and private-institution utilization; she argued that privacy is not about weighing trade-offs but about focusing on the social structures and values supported by privacy. “Privacy is important not only because of its protection of the individual as an individual but also because individuals share common perceptions about the importance and meaning of privacy, because it serves as a restraint on how organizations use their power, and because privacy—or the lack of privacy—is built into our systems and organizational practices and procedures.”22 Privacy protects social values that may not be preserved in the hands of individuals making decisions about the benefits and harms of sharing information.

It has been a challenge to theorize information privacy and conceptual tools that accommodate these changes in information flows. Some theories of privacy lend themselves to digital redemption more than others do. For instance, the right to be left alone provided by Warren and Brandeis is about preventing invasions23 and does not easily reach information that is properly disclosed but becomes invasive as time goes on. Similarly, theories of secrecy and intimacy are about concealing certain information from others. Ruth Gavison’s theory of privacy revolves around access to the self. “Our interest in privacy . . . is related to our concern over our accessibility to others, . . . the extent to which we are the subject of others’ attention.”24 Digital redemption in many ways is about preventing access to part of one’s past that receives more attention than the individual feels is appropriate. Those theories that relate to personhood and control can supplement this notion to further support digital redemption. Westin describes the personal autonomy state of privacy (one of four), in the following way:

Each person is aware of the gap between what he wants to be and what he actually is, between what the world sees of him and what he knows to be his much more complex reality. In addition, there are aspects of himself that the individual does not fully understand but is slowly exploring and shaping as he develops. Every individual lives behind a mask in this manner. . . . If this mask is torn off and the individual’s real self bared to a world in which everyone else still wears his mask and believes in masked performances, the individual can be seared by the hot light of selective, forced exposure.25

Westin follows this passage by describing the importance of personal development and time for incubation, warning against ideas and positions being launched into the world prematurely. Neil Richards has developed the concept of “intellectual privacy,” which recognizes the need for ideas to incubate away from the intense scrutiny of public disclosure in order to promote intellectual freedom.26 Once one presents oneself to the world, however, it is unclear whether privacy would allow for the mask to be put back on and another round of incubation to ensue. Charles Fried explains, “Privacy is not simply an absence of information about what is in the minds of others; rather it is the control we have over information about ourselves.”27 Digital redemption could be understood as exercising control over one’s past information to foster the development and projection of a current self. But even personhood and control do not necessarily provide for retroactive adjustments to information.

Finding that each theory of privacy comes up short in embracing the numerous privacy problems experienced regularly, Solove takes a different, bottom-up approach to understanding privacy.28 He creates a taxonomy with four main categories to guide us through privacy issues: information collection, information processing, information dissemination, and invasion. Information collection refers exclusively to problems that arise from information gathering, such as surveillance by watching or listening and interrogation used to elicit information. Information processing denotes problems that arise from the storage, organization, combination, modification, and manipulation of data, which incorporates security issues, secondary uses, and ignorance of the user. Information dissemination describes the privacy harms that follow the disclosure of information and includes breaches of confidentiality and trust, the release of truthful information to a wider audience, exposure to an individual’s intimate or bodily details, and the distortion and appropriation of an individual’s identity. Finally, invasions include harms resulting from disturbances to peace and solitude as well as interference with an individual’s decisions about private affairs.

Solove’s bottom-up approach to privacy is not normative but is a guide to determining where a violation falls within a more exhaustive, categorized concept of privacy and how to form solutions. It is not clear, however, whether or where the right to be forgotten fits in Solove’s taxonomy. It is difficult to fit into one of Solove’s categories information that is legitimately disseminated but eventually prevents a person from moving on from the past.

One novel model that does leave room for a right to be forgotten assesses privacy violations on the basis of what Nissenbaum calls “contextual integrity.”29 Nissenbaum outlines a privacy framework based on expected information flows. When the flow of information adheres to established norms, the unsettling emotions of a privacy violation rarely occur. Therefore, a jolting realization that your personal information has reached an unintended audience or has been used in an unforeseen way is probably a visceral signal indicating that contextual integrity was not maintained.30

Nissenbaum’s framework assesses a socio-technical system within the existing norms pertaining to the flow of personal information; for a particular context, we maintain values, goals, and principles by focusing on the appropriate and expected transmission of information even when technological advancement and new uses change how the transmission is executed. Like Solove, Nissenbaum does not need a fundamental principle of privacy to be put into practice. The lack of this central underpinning can make contextual integrity problematic when contexts are dynamic or even volatile, unsettled, or questioned.

Still, a right to be forgotten is not necessarily excluded and is potentially even supported by contextual integrity. Noëmi Manders-Huits and Jeroen van den Hoven explain, “What is often seen as a violation of privacy is oftentimes more adequately construed as the morally inappropriate transfer of personal data across the boundaries of what we intuitively think of as separate ‘spheres of justice’ or ‘spheres of access.’”31 Information may be placed in a particular sphere of access that prevents informational injustice—it could also be moved to a different sphere of access over time.

Previously, access to old information about an individual was restricted to information that was recently distributed and for a limited time thereafter. A newspaper article was easily accessible for a few days before it went into a single or a small number of basement archives. Gossip ran its course, and details were quickly lost. Letters and diaries were packed away in drawers and shelves. In contrast, old information today lingers much longer than expected. Facebook’s Timeline is an example of easier access to old information that disrupts the expected information flow and causes the unsettling effect of a privacy violation. MyTweet16 does nothing but present any user’s first sixteen tweets. Google pulls up old personal commentary, photos, posts, profiles—any file that can be crawled by the search engine with your name in it. Specialized search sites like Pipl.com retrieve a one-page report on the searched individual that digs into the deep web, pages that no other page links to.

If access to aged information continues in a way that disrupts contextual integrity, restrictions to the information can be developed to limit access or use to those who need the information. Drawing these lines is important, because expectations change if integrity is not reinforced. Although it may be possible to identify access to old data that violates contextual integrity, it is still a difficult question whether we are willing to move information into another sphere of access when a privacy violation has been identified—necessarily complicating public access. Growing interest in the right to be forgotten from policy makers, industry, and users suggests that many governments may be willing to move information into different spheres of access. The trouble with contextual integrity is that it is based on norms—as the folk musician Bruce Cockburn sings, “The trouble with normal is it always gets worse.”32 When contexts are dynamic, unsettled, or disrupted, it is difficult to ascertain the integrity of a transmission, providing an opportunity for norms to develop in a less intentional fashion. Supporting digital redemption with other theories that are not based solely on norms helps to reinforce the novel idea.

One of the biggest critics of the right to be forgotten, Jeffrey Rosen, offers another useful conceptualization of privacy as “the capacity for creativity and eccentricity, for the development of self and soul, for understanding, friendship, and even love.”33 Shaping and maintaining one’s identity is “a fundamental interest in being recognized as a self-presenting creature,” according to the philosopher David Velleman.34 These theories of privacy focus on threats to the self. The traditional liberal self is one that focuses on protecting “personhood,” which Paul Freund has described as emerging in 1975 and defined as “those attributes of an individual which are irreducible in his selfhood.”35 Expanding on this conception of privacy as protector of individuality, the legal theorist Stanley Benn argues that this must be effectuated as “respect for someone as a person, as a chooser, impl[ying] respect for him as one engaged on a kind of self-creative enterprise, which could be disrupted, distorted, or frustrated even by so limited an intrusion as watching.”36 Irwin Altman describes the privacy function of developing and maintaining self-identity:

Privacy mechanisms define the limits and boundaries of the self. When the permeability of these boundaries is under the control of a person, a sense of individuality develops. But it is not the inclusion or exclusion of others that is vital to self definition; it is the ability to regulate contact when desired. If I can control what is me and what is not me, if I can define what is me and not me, and if I can observe the limits and scope of my control, then I have taken major steps toward understanding and defining what I am. Thus, privacy mechanisms serve to help me define me.37

“Personhood” as a theory of privacy involves the protection of one’s personality, individuality, and dignity—the protection of the autonomy necessary to choose one’s identity. These are relatively new ideas. Julie Cohen takes issue with the “traditional” liberal political theory relied on by modern privacy theorists as a theory that seeks to protect the true, autonomous self. Cohen focuses on the importance of understanding humans in a networked system as socially constructed, dynamic, and situated. She argues, “The self who benefits from privacy is not the autonomous, pre-cultural island that the liberal individualist model presumes. Nor does privacy reduce to a fixed condition or attribute (such as seclusion or control) whose boundaries can be crisply delineated by the application of deductive logic. Privacy is shorthand for breathing room to engage in the processes of boundary management that enable and constitute self-development.”38 This breathing room for the self evolves through what Cohen calls “semantic discontinuity,” defined as “the opposite of seamlessness: it is a function of interstitial complexity within the institutional and technical frameworks that define information rights and obligations and establish protocols for information collection, storage, processing, and exchange.”39 Semantic discontinuity promotes emergent subjectivity—a subjectivity that is socially constructed, culturally situated, and dynamic. Emergent subjectivity promotes the self that is socio-technically constructed but not socio-technically deterministic—the actual self around which to build technological and legal systems. Under Cohen’s theory of privacy, an ongoing record of personal information may create seamlessness. For the dynamic self, creating gaps over time may be as important as creating gaps in any type of informational seamlessness. The right to be forgotten can be understood as the right to retroactively create gaps or boundaries to promote emergent subjectivity and the dynamic self.

“Obfuscation” is the way many users maintain contextual integrity and create gaps and variability for their dynamic selves. While most users do not vigilantly protect against the disclosure of personal information in many settings (discussed previously as a rational decision, considering the amount of work it would entail and the limited ability to see or assess potential harms), users do actively exercise obfuscation by posting pseudonymously, monitoring privacy and group settings in social networks, deleting cookies, lying to websites, utilizing password and encryptions protections, and maintaining multiple accounts and profiles. Woodrow Hartzog and Frederic Stutzman recognize these tactics as natural and important forms of selective identity management. They argue that online information may be considered obscure if it lacks search visibility, unprotected access, identification, or clarity.40

This is a rather broad definition of obfuscation, however. More precisely, it is understood as creating noise in datasets by producing false, misleading, or ambiguous data in order to devalue its collection or use. Being shackled to one’s past can be prevented by actively obfuscating personal data when it is created, but the right to be forgotten is intended to address information created without such foresight. If that were easy to do, the socio-technical problem at issue would be easier to solve. Instead of retroactively turning personal information into false or misleading information, the right to be forgotten seeks to diminish the ease of discoverability of old personal information. I refer to this closely related concept as obstruction. Obscurity by obstruction is simply any means of creating challenges to the discoverability of personal information. Users’ reliance on obscurity makes it a natural place to look for answers as well as highlights the importance of context. Obscurity offers an opportunity to have privacy in public, but only if it is respected or protected.

Obstruction allows for information to be gray (somewhat private and somewhat public) and adheres to the idea of “good enough” privacy. The law professor Paul Ohm argues that instead of perfection, privacy- and transparency-enhancing technology should require seekers to struggle to achieve their goal.41 A common response to digital-redemption initiatives is that there is no way to find and delete all the copies of the relevant personal information, but for most users, only easily discoverable information matters. If the right to be forgotten sought perfect erasure from all systems everywhere, it would not have a leg to stand on. Instead, obstruction clearly signals something more measured than complete forgetting. And so new theories of privacy and information protection allow the right to be forgotten to be considered retroactively, creating gaps using obstructions to support the dynamic self and maintain contextual integrity.

Using these theories of privacy, we can start to break down the right to be forgotten into workable concepts, an exercise it desperately needs. Generally, the right to be forgotten “is based on the autonomy of an individual becoming a rightholder in respect of personal information on a time scale; the longer the origin of the information goes back, the more likely personal interests prevail over public interests.”42 It has been conceived as a legal right and as a value or interest worthy of legal protection. The right to be forgotten represents “informational self-determination” as well as the control-based43 definition of privacy and attempts to migrate personal information from a public sphere to a private sphere. It represents too much.

Bert-Jaap Koops draws three conceptual possibilities: (1) data should be deleted in due time, (2) outdated negative information should not be used against an individual, (3) individuals should feel unrestrained in expressing themselves in the present without fear of future consequences.44 Paul Bernal45 and Jef Ausloos46 emphasize that the right is only meant to offer more user control in big-data practices. Bernal argues that the right to be forgotten needs to be recast as a right to delete to combat negative reactions and focus on the most material concerns. This should be done as a part of a paradigm shift: “the default should be that data can be deleted and that those holding the data should need to justify why they hold it.”47 Ausloos similarly argues that the right to be forgotten has merit but needs a refined, limited definition. He argues, “The right is nothing more than a way to give (back) individuals control over their personal data and make the consent regime more effective”48 and should be limited to data-processing situations where the individual has given his or her consent.

On the other end of the spectrum, Napoleon Xanthoulis argues that the right should be conceptualized as a human right, not a “control” right,49 and Norberto Andrade argues that the right should be one of identity, not privacy, stating that the right to be forgotten is the “right to convey the public image and identity that one wishes.”50 Xanthoulis explains that rights require an important interest and that a human right requires something more; human rights are only human interests of special importance.51 Xanthoulis succinctly explains that privacy has been proclaimed a human right, so reinvention has to be firmly situated within privacy to qualify as a human right. Andrade conceptualizes the right to be forgotten as one established under an umbrella right to identity, that data protection is procedural and a method to fulfill other rights, but that the right to identity is the “right to have the indicia, attributes or the facets of personality which are characteristic of, or unique to a particular person (such as appearance, name, character, voice, life history, etc.) recognized and respected by others.”52 It is therefore not a privacy right exactly, because it does not deal with private information, but as an identity right, the right to be forgotten could assist the “correct projection and representation to the public.”53 None of these conceptualizations is necessarily right or wrong; they are simply talking about different things.

The right to be forgotten is a concept that needs to be broken apart to be manageable. Efforts to address the potential harms derived from numerous collections of digital pasts in both the U.S. and the EU have been discussed, specifically the proposed language in the EU’s Data Protection Regulation and the U.S.-proposed Do Not Track Kids legislation. The proposed regulations focus on the individual’s rights that remain with a piece of information after it leaves the individual’s control. These developments have resulted in inappropriate conceptual convergence. Breaking down the concepts and applications within the right to be forgotten helps to more effectively consider these inevitable issues.

Two versions of the right to be forgotten provide for muddled conceptions and rhetoric when they are not distinguished. The much older one—droit a l’oubli (right to oblivion)—has historically been applied in cases involving an individual who wishes to no longer be associated with actions as well as rare other circumstances, as discussed in chapter 1. The oblivion version of the right to be forgotten finds its rationale in privacy as a human/fundamental right (related to human dignity, reputation, and personality). A second version of the right is one offering deletion or erasure of information that has been passively disclosed by the data subject and collected and stored without providing public access. In the second context, a description of the right to be forgotten could instead be called a right to deletion. A handful of scholars have commented on each version separately and both together.

Compare two UK cases that struggle to delineate between interests related to content and data. Quinton v. Peirce & Anor involved a local election in 2007 when one politician, Quinton, claimed that his opponent, Peirce, had published misleading (not defamatory) information about Quinton in campaign materials. Quinton claimed both malicious falsehood and violations of the accuracy and fairness provisions of the DPA (recall that this is Britain’s national data-protection law, adopted to comply with the 1995 DP Directive). Malicious falsehood of course requires the plaintiff to prove malice, which is quite difficult and therefore rarely successful; Quinton did not sufficiently establish this element of his claim. Justice David Eady then applied the DPA, finding that Peirce was a data controller and that the journalism exemption was not applicable, but Eady would extend this argument no further. To the accuracy claim, he saw “no reason to apply different criteria or standards in this respect from those . . . applied when addressing the tort of injurious falsehood.”54 On the fair-processing claim, which was argued to require that the data subject be notified in advance of the leaflet’s distribution, Eady declined “to interpret the statute in a way which results in absurdity.”55

In Law Society, Hine Solicitors & Kevin McGrath v. Rick Kordowski, plaintiffs sought to prevent the defendant from publishing the website Solicitors from Hell, which intended to expose “corrupt, negligent, dishonest, crooked, fraudulent lawyers,” and similar websites in the future. Plaintiffs sued for libel, harassment, and violations of the DPA’s accuracy and fairness requirements. The claim was initially rejected by the information commissioner, who explained,

The inclusion of the “domestic purposes” exemption in the Data Protection Act (s. 36) [which excludes data processed by an individual only for the purposes of that individual’s person, family, or household affairs] is intended to balance the individual’s rights to respect his/her private life with the freedom of expression. These rights are equally important and I am strongly of the view that it is not the purpose of the DPA to regulate an individual right to freedom of expression—even where the individual uses a third party website, rather than his own facilities, to exercise this. . . . The situation would clearly be impossible were the Information Commissioner to be expected to rule on what it is acceptable for one individual to say about another be that a solicitor or another individual. This is not what my office is established to do.56

Justice Michael Tugendhat disdainfully disagreed: “I do not find it possible to reconcile the views on the law expressed in the Commissioner’s letter with authoritative statements of the law. The DPA does envisage that the Information Commissioner should consider what it is acceptable for one individual to say about another, because the First Data Protection Principle requires that data should be processed lawfully.”57 Tugendhat did not grant the website domestic purpose or journalistic exemption, leaving a lot of the web fair game for data-protection claims. It is unclear how privacy and defamation civil claims are to be integrated with data protection when these types of information are not separated.

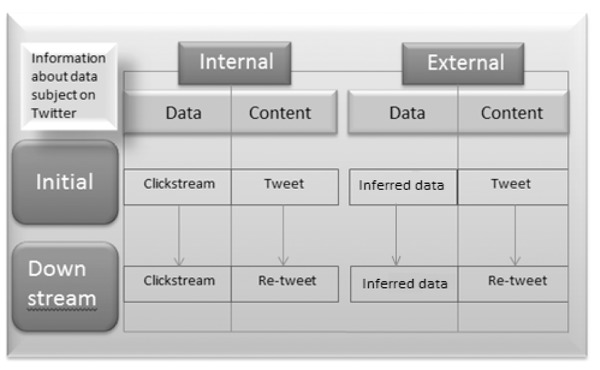

The right to be forgotten could be applied in an absurd number of circumstances and cannot apply to all information related to all individuals in all situations, no matter in what jurisdiction the right is established. Possible applications of the right illustrate the very different circumstances that the right to be forgotten attempts to take on and supports an argument for conceptual separation. The chart in figure 1 represents all of the possible situations in which a right to be forgotten could apply. The chart headings should be read as follows:

- ▷ Data is passively created as a user (automated “clickstream” data).

- ▷ Content is actively created information (nonautomated “expressive” content).

- ▷ Internal designates information that is derived from the data subject whose personal information is at issue.

- ▷ External information is that which is produced about the user by someone else.

- ▷ Initial location is where the content was originally created or collected (e.g., Twitter).

- ▷ Downstream is where it may end up (e.g., retweets, data broker).

Data about a user may also be generated by the data collected and analyzed by another user if the two share similarities such as gender, age, geography, shopping or searching habits, personal or professional connections, or any number of data points; this is called inferred data. The data is generated passively by another user and may remain with the initial collector to provide more personalized service or be traded downstream to assign data to the data subject.

The right to be forgotten may apply to any or all of these cells, columns, or rows, depending on the legal culture seeking to establish it. However, distinctions between legal cultures have been ignored. The conflation of the right to oblivion and the right to deletion has led to much confusion and controversy. Under this conceptual divide, a right to deletion could only be exercised to address data. A right to oblivion would apply to content, such as social media posts, blog entries, and articles. Oblivion is founded on protections of harm to dignity, personality, reputation, and identity but has the potential to collide with other fundamental rights. However, oblivion may be relatively easy to exercise in practice, because a user can locate information he or she would like the public to forget by utilizing common search practices. A right to deletion, on the other hand, would apply to data passively created and collected. It is meant to shift the power between data users and controllers. Deletion is a data-participation right, allowing a data subject to remove the personal data he or she has released to companies that collect and trade data for automated processing, and it may be easier to implement legally because few users have access to this personal information.

The problem with conflating the concepts of deletion and oblivion within the right to be forgotten is that both treat all data in the matrix shown in figure 1 the same way, but the concepts are very different. This is particularly problematic when applying the same analysis and procedures to content (actively created, available online) and data (passively created, privately held). Circumstances surrounding passively created data, which is collected, processed, and stored with consent (to use the term loosely) and privately held, have different interests associated with them than does actively expressed content created online—and therefore, they deserve different treatment.

On the basis of the distinctions just drawn, the right to deletion could be applied to data that is passively created internally by the data subject and that is held by the initial controller or passed downstream, without initiating the more troubling act of deleting publicly available information from the Internet. And more precise procedures for removal or limiting access could be constructed for the right to oblivion that would take into account the more numerous users and uses associated with disclosed personal content.

Versions of Fair Information Practice Principles that include a right to deletion as one of the user-participation principles fall within the concept of the right to deletion applying to data held by the initial data controller and likely applying to downstream data controllers. California’s child privacy law falls squarely within the oblivion conception of the right to be forgotten, focusing on reputation and development by offering a right to delete damaging content. The CJEU’s interpretation of the EU DP Directive and DP Regulation combines oblivion and deletion—a problematic combination.

The proposed Regulation still refers in paragraph 1 to data collected for specific purposes that have expired (conjuring up notions of data traders and behavioral advertising) and then in paragraph 2 includes information that has been made public (suggesting that a blog entry that identifies the data subject must also be erased or at least obstructed upon request). The right to be forgotten would be well served by language delineating clear conceptual bases in order to anticipate the way in which the right and exceptions will be applied in relation to the various interests they represent.

Even with these options, there is a lot of uncertainty surrounding digital information. We do not really know what types of digital information are intended to be temporary. Certain print information eventually became categorized as temporary; it is called ephemera. A man named John de Monins Johnson (1882–1956) made a hobby of collecting printed ephemera, things like advertisements, menus, greeting cards, posters, handbills, and postcards. These are pieces of paper information intended to be short-lived and discarded. The collection is held in an esteemed library because it provides valuable insight into the past on a variety of fronts. It is mentioned here because it represents a category of momentary human communication and the reasons to hold onto it. By choosing categories in the chart, we utilize the law to label pieces of information as digital ephemera and will need to also find ways to preserve its future value.