History in the Balkans is often less the study of past events and more an examination of national pride, with a good deal of myth and legend thrown in for good measure. Though Bulgaria’s history is not exceptional, the simple fact that the Cyrillic alphabet was invented by followers of two Bulgarian monks has ensured that the modern Bulgarian story has been well documented for far longer than that of most other nations in the region.

Valley of Kings

In 2004 a number of archaeological discoveries were made south of the Stara Planina Mountains in an area dubbed the ‘Valley of the Thracian Kings’. The findings include a 2,400-year-old Thracian shrine near Shipka, believed to be the burial chamber of King Seuthes III, rival to Alexander the Great.

Thracians, Rome and Byzantium

While there are traces of ancient settlements in Stara Zagora, the history of Bulgaria really begins with the emergence of the Thracians on the Danubian plain around 1200 BC. The Thracians were an amalgamation of earlier tribes, who may have migrated to the region from Mesopotamia. Archaeological evidence suggests that there was certainly communication between the Near East and the Balkans across the Black Sea by the end of the 2nd millennium BC.

The first documented history of the region comes from the Greeks, who began to visit Thrace in the 7th and 6th centuries BC, gradually extending their influence from the coast inland. Though Persian invasion briefly disrupted this Hellenisation in the 6th century BC, Philip of Macedonia conquered Thrace in 346 BC and began colonising the area, building settlements, including one that carried his name, Philopopolis, the present-day Plovdiv. Under Philip’s son, Alexander the Great, the Thracian interior was fully opened up to Greek settlers and merchants, who over the next 200 years fused with the Thracians to form a distinct ethnic group.

Rome conquered Thrace in AD 46 and wasted no time in colonising the area. The region prospered. New towns were settled, including Serdica (Sofia), Augusta Traiana (Stara Zagora) and Durostorum (Silistra). But the Roman Empire became overstretched and in AD 260 Dacia (present-day Romania, to the north) was abandoned to Barbarians. Thrace, too, came under constant Barbarian attack. The Roman Empire was split between Rome and Constantinople (Byzantium) in 395, but it was not until the reign of Emperor Justinian I (the Great, 527–65) that imperial authority was once again imposed over all of present-day Bulgaria.

The Slavs

Though Justinian encouraged culture and education, fortified the cities of the border lands and quickly settled Serdica and Philipopolis with great numbers of people, the continued power vacuum in Dacia to the north meant that Thrace remained susceptible to invasion. Barbaric, ill-organised tribes such as the Pechenegs and Avars did not get far, but in the 5th century the Slavs, a much larger tribe, swept into the Balkans. Their origins are unclear, though they migrated into the Balkans from a region thought to be in Poland and Ukraine, and are the forefathers of present-day Croats, Czechs, Serbs, Slovaks, Slovenes, Poles and Russians, as well as Bulgarians. So immovable were these Slavs that they were not opposed by the Byzantine rulers, who allowed them to settle.

The First Bulgarian Kingdom

No sooner had the Slavs gained hegemony over Thrace than a new wave of immigrants arrived, this time the Bulgars. Politically astute and brilliant horsemen, the Bulgars were described more than once in Byzantine dispatches as ‘barbaric and vulgar’. Originating in a region east of the Black Sea, perhaps as far as the Caspian Sea, the Bulgars followed the Black Sea shore, entering Thrace by the Danube Delta. As many as 250,000 came and, led by Khan Asparuh, they established in 681 the Parvo Bulgarsko Tsarstvo (the First Bulgarian Kingdom). Its capital was Pliska.

The next 200 years are the most fiercely debated in Bulgaria’s history. While many Bulgarian historians insist that the tolerance of the Slavs and the enlightened rule of the Bulgars meant that the two nations fused effortlessly – with the Slavs eventually accepting Bulgar dominance – most Western historians see things differently. They claim that only political expediency – the Bulgars needed Slav support – held the uneasy alliance together.

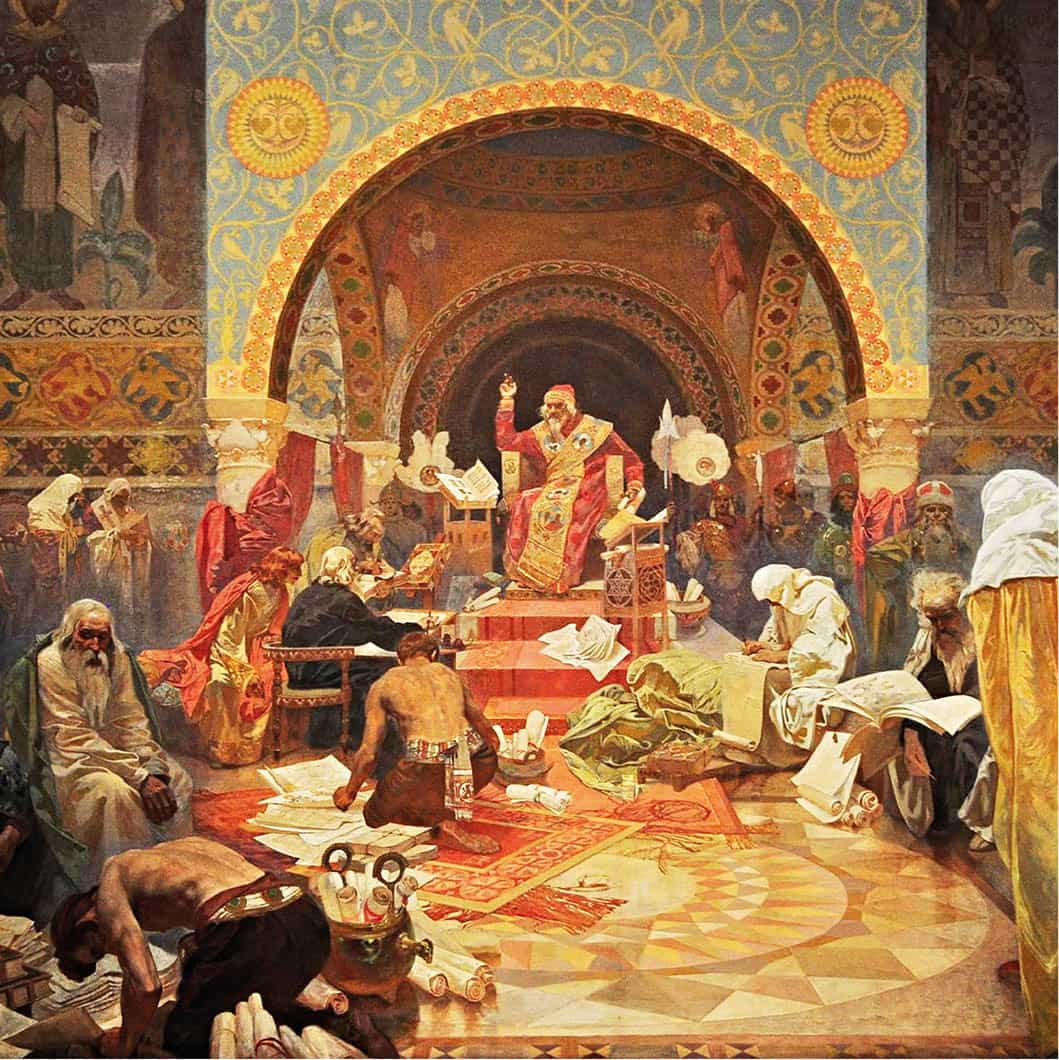

Simeon the Great, by Alfons Mucha

SuperStock

The Cyrillic Alphabet

Although the alphabet only took one man’s name, Cyrillic is the work of two monks: Konstantin-Cyril and his brother Methodius. In 855 the two brothers retired to a monastery in Salonika (in modern Greece) to formulate a satisfactory way of rendering the scriptures into the Slavic language. Seven years later they emerged with a rune-based script known as the Glagolitic alphabet, which one of their former pupils helped adapt to create a prototype of today’s Cyrillic alphabets. This in turn was finessed by the various Slavic peoples to fit local nuances. Cyrillic is used today in Bulgaria, Serbia, Macedonia, Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, Mongolia, Turkmenistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgystan (for more information, click here).

Simeon the Great

Of all Bulgarian leaders, one remains more revered than any other: Simeon the Great (reigned 893–927). During his reign, Bulgaria conquered huge swathes of Europe and became the largest empire on the continent, stretching from Greece to Ukraine, from the Black Sea to the Adriatic. Simeon, who had been schooled in Constantinople and knew the value of a good education, used the newly created Cyrillic alphabet as a means of uniting Slavs. More than a warrior, Simeon was a man who realised the importance of culture in uniting a nation, and his patronage of the arts gave birth to the first real age of Bulgarian literature, painting and sculpture.

Yet Simeon greatly overstretched his resources and on his death left no heir capable of replacing him. The Bulgarian empire collapsed, the country once again falling under the spell of Constantinople.

The Second Kingdom

Byzantium, however, was by this stage an empire in disarray, and it was not long before the Bulgarians regrouped and reclaimed their country; albeit somewhat reduced in size from its days under Simeon. Two brothers, Peter and Assen, led a Bulgar uprising at Mizia, and declared a new Bulgarian Kingdom, with its capital at Veliko Tarnovo.

Cyril and Methodius, fathers of the Glagolitic script

Shutterstock

Assen’s son, Tsar Kaloyan, further extended Bulgaria, recapturing Varna in 1204, the year the knights of the Fourth Crusade sacked Constantinople and declared their Holy Eastern Empire. Kaloyan was unimpressed and shortly afterwards defeated the Crusaders and set about creating an empire of his own. He was murdered in a palace coup and replaced by Tsar Boril, briefly, before the far more satisfactory Tsar Assen II took power in 1218. Expansion recommenced and Bulgaria was again – briefly – the size it was under Simeon.

Ottoman Domination and the National Revival

The defeat of the Serbs by the Ottoman Turks at Kosovo Polje (Blackbird Field, in Kosovo) in 1389 sealed the fate of the Balkan Peninsula. In 1393, Veliko Tarnovo was captured by the Turks, and three years later all of Bulgaria became part of the Ottoman Empire. This period of Turkish rule, which lasted nearly 500 years, came to be called the Ottoman Yoke.

The list of atrocities committed by the Turks during the Yoke is a long one. At least half the Bulgarian population was killed or left to starve in the first 50 years following the conquest, while many of those who survived were forced to convert to Islam – though a good number resisted. Arabic replaced Bulgarian as the official language used at court, and Greek became the language of the church.

The occasional uprisings against the Turks, including those at Veliko Tarnovo in 1598 and 1686, never succeeded in bringing about anything resembling change. It was the dominance of Greek priests, appointed by the Turks to oversee the Bulgarian church, which forced a number of Bulgarian intellectuals to take measures to ensure that the Bulgarian language and a Bulgarian-centred history survived. Many intellectuals, such as Bogdan Bakshev, Archbishop of Sofia, were forced to publish their works outside of Bulgaria. Bakshev’s History of Bulgaria caused a furore when published in the 17th century, as did Pasii of Hilender’s History of the Slav-Bulgarians (1762). Both works helped rekindle Bulgarian nationalism in the 19th century – a period known as the National Revival. Economics also played a part in the Revival, as an increasing number of wealthy Bulgarians were able to travel to trade in areas not dominated by Turkey, and in doing so returned with new liberal ideas that were anathema to Bulgaria’s rulers.

Bulgarian freedom fighter statue at Dryanovo Monastery

Patrick Frilet/REX/Shutterstock

The Struggle for Independence

In 1859, with Russian help, Romania rid itself of the Turks. Ten years later the Bulgarian Revolutionary Committee (BRCK) was created in Bucharest, uniting disparate nationalists for the first time under one group behind one leader, Vasil Levski. The capture and execution of Levski in 1873 provided the movement with a martyr, and in April 1876 it was ready to launch an uprising against the Turks.

During the April Rising, more than 30,000 rebels died, evoking great sympathy from Russia and the Western powers, which until then had urged Turkey to grant Bulgaria autonomy, not independence. Russia declared war on Turkey in 1877 and, after a year of heavy fighting, the Ottoman Empire was forced to sign the humiliating San Stefano Peace Treaty. On 3 March 1878, Bulgaria declared independence.

The Third Bulgarian Kingdom

The other great powers – Britain, France and Austria-Hungary – were not happy with the treaty, and the Congress of Berlin in July of 1878 reversed much of the San Stefano Treaty. Macedonia was returned to Turkey in its entirety, while the rest of the country was divided, creating two provinces that had to pay annual tributes to the Sultan of Turkey, while remaining nominally independent.

Searching Europe for a monarch, the Bulgarian assembly chose Alexander Battenberg to serve as prince, who repaid them by creating an autocratic state in which he wielded considerable power. He is remembered favourably, however, for managing to reunite the divided country (in 1885) very much against the will of Britain and France. He was replaced as prince on his death in 1887 by Ferdinand Saxe-Coburg, who changed his title from prince to tsar in 1908. In the same year Bulgaria again proclaimed full independence from Turkey, and with the Ottoman Empire in chaos, nobody objected.

Boris III in 1920

Getty Images

The Balkan Wars and the Difficult 1920s

Bulgaria united with Serbia and Greece in an alliance designed to rid the Balkans of the Turks forever. The First Balkan War of 1912 saw them achieve that goal, almost capturing Istanbul in the process. Then the victors fought between themselves over the spoils in 1913, Bulgaria suffering defeat at the hands of erstwhile allies Serbia and Greece. As a result Macedonia was lost to Serbia, and the Dobruja was lost to Romania.

World War I saw the vast majority of the population side with Russia and its allies, while the government – a sworn enemy of Serbia, Russia’s ally – backed the Axis powers. The result was carnage, and defeat in September 1918, after which deserting soldiers attempted a coup, which failed, though it did force Ferdinand to abdicate in favour of his son, Boris III.

Macedonian nationalists of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (IMRO) were a thorn in Bulgaria’s side throughout the early 1920s. Opposed to the newly created Yugoslavia, the IMRO was hostile to the policies of Prime Minister Alexander Stamboliski, who sought peaceful co-existence with Yugoslavia. In alliance with military officers, who also opposed the prime minister, the IMRO staged a coup in 1923, killing Stamboliski and creating a shaky coalition that managed to hang on to power, with Boris III still nominally the head of state, until 1935. In November of that year, Boris decided he had had enough of politicians and dismissed the lot, creating an absolute monarchy.

World War II

Bulgaria sided with Germany for a second time in 1941, though the country remained to all intents and purposes neutral, refusing to send troops to the Russian front despite German protestations to do so. There was a German military presence in the country throughout the war, however, and as the tide turned and the Red Army swept through the Balkans in 1944, Bulgaria was quick to see which way the wind was blowing, changing sides on 9 September 1944, a date until recently celebrated as Liberation Day.

Thompson village

A tiny village in the Iskar Gorge is named after Major Frank Thompson, sent to Bulgaria to evaluate the fighting potential of the local partisans during World War II. Thompson, a committed Marxist, quickly went native and was killed fighting alongside the partisans in 1944. After the war he was revered by the Bulgarian Communist regime as an anti-fascist hero, and though many towns and villages in Bulgaria that carried Communist-era names have now had their former names restored, the village of Thompson remains Thompson.

Communism

With the Red Army firmly in control of the country, it was impossible for Bulgaria to avoid a post-war Communist takeover. Bulgarian Communists who had fled to Moscow in the 1920s and had survived Stalin’s purges now returned, led by Georgi Dimitrov, who had been leader of the Comintern in the 1930s. Elected in a mockery of an election as prime minister in 1946, Dimitrov immediately had a Communist Party-dominated parliament rubber stamp a new constitution (based on that of the Soviet Union), which abolished the monarchy and created the People’s Republic of Bulgaria.

Dimitrov died in 1949 and was replaced by Valko Chervenkov, who eradicated all actual or potential opponents, most of whom perished in the death camps of Belene, on the Danube. Chervenkov fell out of favour with Moscow after Stalin’s death in 1953 and was replaced by Todor Zhivkov, who remained absolute ruler until 1989. Zhivkov’s rule is marked by economic stagnation and utter subservience to the Soviet Union.

Return to Democracy

Eastern Europe’s year of revolutions and political change, 1989, appeared to have passed Bulgaria by and, as late as November, Zhivkov’s grip on power appeared as tight as ever. He was undone, however, by reformers inside the Communist Party, who forced him to resign, arresting him on charges of fraud. The reformers, who had overseen small but significant changes in the economy from the mid-1980s onwards, elected Peter Mladenov as head of the Central Committee, promising multiparty elections for June 1990. Since then Bulgaria has struggled with the transition to a market economy, but remained relatively politically stable. Simeon Saxe-Coburg, who was king briefly in the 1940s, oversaw Bulgaria’s entry to Nato, but failed to deal with rampant corruption. He was replaced in 2005 as prime minister by Sergei Stanishev, a left-winger, who secured Bulgaria’s entry to the EU in 2007. Since 2009, the centre-right former mayor of Sofia, Boyko Borisov, has dominated Bulgarian politics, and is currently serving his fourth spell as prime minister.