Chapter 8

The T-Chart

When my oldest son, Santino, was four, we noticed that his levels of frustration and aggravation were rising. My wife and I are fans of letting our kids struggle, but something wasn’t right. He chewed his nails until they bled. His acting out was a growing concern.

By nature, Santino is crazy and fearless. He’s the apple that didn’t fall far from the tree. Whenever I got into trouble as a boy—which was too often—my dad would say to me, “Hijo eres, Papa serás!” In English, this means, “A son you are, a dad you’ll be.” Santino is single-handedly paying me back for all the mischief I stirred up as a kid. It was hard to watch the playful, spirited son we knew wrestle with his behavior and not know how to help him.

We asked our pediatrician for help, and he referred us to a child psychologist. After our initial meetings, we learned Santino was facing developmental challenges that affected his capacity to deal with frustration, which created very unhealthy levels of stress for him.

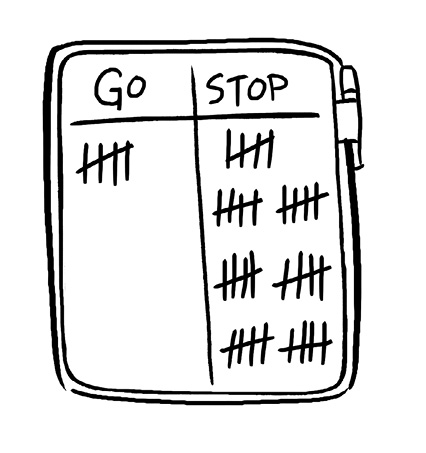

To help our son manage his condition, the psychologist sent us home with an exercise. He told us to take a sheet of paper and draw a large T across the top. The left-hand column would be labeled “Go” and the right column would be labeled “Stop.” And then the psychologist asked my wife and me to track what kind of commands we gave our son. A Stop command was an instruction on what he couldn’t do, like “Don’t stand up in your chair at the table.” A Go command was an instruction telling him what he could do, like “Please put your seat in the chair.” Little did I know how this exercise would rock my soul to the core.

The next day we started tracking our commands. I found the majority of my instructions were Stop commands. The tick marks accumulated on the right side of the page. “Don’t use your shirt to clean your hands.” “Don’t interrupt Mom and Dad while we’re talking.” On the second day, I literally broke down and cried. Our son was overwhelmed with frustration, and we just compounded his struggle by telling him over and over what he couldn’t do.

We knew what had to change, though we quickly discovered how difficult it was to be more thoughtful when communicating with Santino. We worked hard to rephrase our Stop commands into Go commands. “Please use your napkin to wipe your hands.” “Please wait patiently for us to stop talking and then ask your question.” We only used a Stop command when it was safety related.

After three weeks, we noticed Santino’s improvement. He was starting to act more like the boy we knew. He was less stressed, and in time he quit biting his nails. Even now we notice that when we regress and return to our old habits, Santino’s behavior suffers too. It’s an immediate reminder of the impact of our communication.

Working on commands at home with Santino inspired me to evaluate how things were going at the office. I initiated individual conversations with my team and asked how I made them feel during tactical discussions. One leader told me I was “quizzing” or “taking him down a rabbit hole” by the way I asked questions. Another leader felt I didn’t trust their decision-making. Yet another confessed to feeling like they were doing everything wrong whenever we got off the phone. I was grateful they trusted me enough to be honest with me.

I was disheartened and concerned. I had great people that I trusted, and I loathed any hint of micromanaging. If anything, I felt like I undermanaged at times. But the exercise revealed that I held people in check in a more subtle, imperceptible way. I wanted to be encouraging while also giving people the autonomy we all crave. I wanted people to feel empowered when we spoke, not deflated. If my questions and tone communicated a lack of faith in people and their decisions, I was simultaneously discouraging them and undercutting the agency I wanted for them. I struggled with communicating in a dispiriting way, making the opposite of the positive impact and influence I wanted to convey.

When people ask a question, it contains two parts. There’s the “what” part of the question: the words that come out of our mouths. There’s also an unspoken “why”: the reason for asking the question. The “what” is least important. Instead, it’s better to focus on the “why.” There’s always a reason, whether it stems from a doubt, an insight, or a need for assistance that prompts a question. Most leaders don’t respond to questions with discerning follow-up questions to better understand why the question was asked in the first place. As a leader, you need to get to the “why.”

People generally won’t say what really bothers them—they conceal the “why.” In business, it’s usually because someone sees the situation differently and has a concern, or they are missing information and don’t want to reveal their knowledge gap. They are afraid of any circumstance that may reflect badly on them. If we don’t acknowledge this dynamic in our conversations, we can’t get past the confusion or frustration and move toward active solutions.

By instinct or training, often leaders know it’s best to ask a lot of questions and do more listening. But the way you ask questions may be counter-productive, making people feel as though they have been caught doing something wrong. In turn, they aren’t getting the helpful direction they need. As long as this condition continues, no one is going to feel encouraged or autonomous in their role. As a leader, I had to change the way my team felt every time I had a conversation with them.

I decided to tell the story of my experience with Santino. It was wrenching because it was such a hard lesson to learn as a dad. The twenty leaders I spoke to via conference call responded with prolonged silence. Rather than feeling awkward or uncomfortable, I got a sense of empathy and understanding. The team finally understood how deeply I wanted to encourage and energize each of them when we spoke.

To change the impression and impact you make in every conversation, from the water cooler to the boardroom, there are a few techniques to practice. When you need to clarify a question, paraphrase it and add a “why”—“This is what I hear you asking me and why.” Be forthright and get to the most important part of any question early in the conversation. Another way to get to the root of “why” is to pay close attention to your tone and ask for elaboration using a phrase like, “Help me understand what you see a little better.” The goal is to foster collaborative discussions that allow the whole organization to move forward.

Change your nonverbal language if you’ve developed bad habits. Even silence communicates volumes. If your body language is screaming, “Are you freaking kidding me?” you’ll only undercut your intention to be supportive. Because 90% of communication is nonverbal, this is generally the hardest practice to change. But until you do, you’ll be sending mixed messages, completely defeating your progress from the first two techniques.

An important benefit of this gift is how it leads to recognizing people for what they do well. As you become more encouraging in conversations, it’s natural to reinforce positive behaviors you are trying to cultivate. Getting to “why” and using Go commands along with encouragement and recognition help satisfy a person’s legitimate need to be appreciated and valued. The impact on happiness and engagement can’t be matched. And it’s free!

I believe the frustration we see in the eyes of those we are honored to lead is an invitation. Your role as a leader is to give people confidence every time you give direction. They must feel that you understand their reasoning, and you must question “why” until you do. Keep your powerful and unconscious body language in check, and don’t leave the discussion until that individual has a sense of optimism that they can get the job done. The gift you get in return is seeing the positive outcomes that are a result of conversations that are as supportive as you’ve always intended them to be.

Questions to Guide Your Journey

1.What do your people hear when you give direction—Stop or Go?

2.How are you building confidence with every conversation?

3.What message is your tone and non-verbal communication sending when you ask a question?

Flash-Forward

When Santino was nine, he said something to me that made me feel both proud and humbled. It was a Saturday afternoon, and we were hanging out at home when I came upstairs and saw a big stack of Pokémon cards and a pile of Legos in the hallway. They were scattered everywhere. He had stepped away for a moment to go to the playroom to get more Legos. I kicked into Grumpy Dad mode when I saw the mess. I was probably hungry. I said, “Santino, don’t scatter your stuff everywhere like that. We have to walk through here!”

He looked right up at me and said, “Then can you tell me where I can do it? ’Cause I’m trying to build this cool house out of Pokémon cards and Legos and it keeps falling down.” Touché, little man. Thanks for keeping Dad in check.