Chapter 14

Become a Student of Struggle

Early in the morning following my eighteenth birthday, I waited outside the gym at my school for the Army recruiter. My parents didn’t know, but I had told a short list of people that I was planning to enlist. They were all sworn to secrecy. We drove forty-four miles to Hobbs, New Mexico, where I boarded a bus to the Military Entrance Processing Station in Amarillo, Texas.

The following day, I was sworn into the Army, and the recruiter dropped me off at my house in the early evening. I feared my parents knew I hadn’t stayed at my best friend’s the night prior, and I knew my dad would be furious. I was the first of my siblings to take the oath, and we all knew you didn’t dare test my dad’s authority. I walked in the front door, and my dad was sitting at the head of the table. He immediately stood when I walked in, and I could tell by his body language that he was not happy. I had to act fast. Walking in my direction, he began peppering me with questions about where I stayed the prior evening. I said nothing and tossed the folder with my Army enlistment paperwork on the table.

I then told him in Spanish, “I joined the Army, Papa.”

His body language immediately softened and he silently stared.

“Do you know what you’re doing?” he asked.

I responded, “Yes. I’m completing your dream, Papa.”

Tears welled up in his eyes as he turned around and walked toward the window in the kitchen. Looking out, his shoulders shook a bit, and he raised his hand to wipe the tears away. He waited a moment before he walked out the back door. I looked over at my mom, who had tears on her face. It was the second time in my life I’d seen my dad cry.

Early in my life, he shared the story of his dream as a teenager to join las Fuerzas Armadas de México—the Mexican Army. Joining the military was the only way he saw then to break the generational cycle of poverty that had been passed down in the family. His dream had been derailed by severe family hardships as he was coming of age, and he was unable to enlist. He would have to find another way out while his struggles continued to shape him for many years.

Something in his tone when I heard the story made my heart ache. I recall thinking how I would do anything to mend that hole. The year following the bus story, I vividly remember realizing that perhaps I could help him. The military recruiters had started visiting more often, and the more I sat with them, the more I wanted to serve.

That last week when I sat with my dad before he passed, he told me how much it had meant that I had done that for him. We never discussed it that evening after I told him I had enlisted. This time, when I heard the story, we both wept. His tone was different. He told me he was proud of me and that I had filled the hole in his heart.

We all have someone who has struggled through hard choices so that our own may be different—better, perhaps. Early on and throughout his life, my dad faced many struggles. He constantly told me stories about the gifts those struggles gave him. When his grandchildren fell down, he would always smile and say, “That’s how we learn.” I always felt that the least I could do was to show him and my mother how grateful I was by becoming a student of their struggles. Choosing to join the Army was my gift to my dad: I would complete his dream.

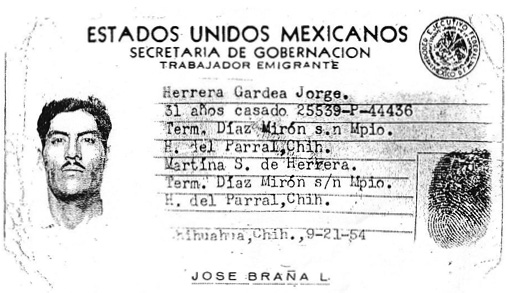

Every day when I walk into my office, the first thing I see above the light switch is a picture of my dad’s bracero card. It keeps me grounded and focused as I remain a student. That card is my proudest symbol of how struggle has been my teacher.

So how do you begin your journey as a student of struggle?

Start by openly inviting struggle into your life. Too many people silence or ignore their struggles. We all struggle, and it will be with us for as long as we live. You must decide for yourself that struggle is a good thing, that struggle is a gift.

Once you do, identify what your struggles have been and reflect deeply on them. As you reflect, consider how they have helped you become a better version of who you are today. How have they made you stronger? More resilient? More compassionate? The answers to these questions are the powerful gifts that have shaped your life. Those are the gifts. This is the work that will help you better understand your leadership potential and who you are becoming.

From there, you will have the clarity you need to begin the journey to become the leader you imagine. Your desire to improve must overrule your need for comfort. You will have to confront the emotions that struggle brings up to develop the courage to share your stories and your gifts. There is an incredible need in the world for us to learn from one another and help others, to be more compassionate and kind. You must share your gifts of struggle so that we all may become better people.

For aspiring leaders and those of you early in your leadership journey, you’ll soon learn that the lessons outlined in these chapters are not a chronological list. There is a lot of ambiguity in leadership. Some of you will want a “how to” checklist. You want the answers to the test. I get it.

There is healthy tension between the lessons I shared in this book. I encourage you to go off the beaten path in Chapter 10, and then Chapter 11 says to trust the process, that less is more. For someone early in their leadership journey, this could be perceived as a mixed message. I understand that it can be confusing. Leadership isn’t easy. It’s complex, overwhelming, and messy. You’re going to have to struggle through situations for yourself, like I did.

But what I can do is encourage you to think of these lessons as an “and” not an “or.” Your struggles will be situational and unique to you—identify and study them first, then determine which lesson will best guide you. Sometimes it will be a combination of a few, and the others may not apply. Let your struggles decide. The more you do this, the better you will become at dealing with the ambiguity of becoming a leader.

Let me end with this:

I know you can do it.

You have more potential than you realize.

All Hail the Underdogs!