![]()

THE society Virginians established during the first fifty years of the colony’s existence had been geared to function in the face of heavy mortality. One of its features was the annual arrival of new workers to replenish the dying labor force. The decline of mortality and the increase in population did not stop the flow of immigrants. Until the last two decades of the century the annual arrivals were probably not much under 1,000 a year and in some years much more. New workers were still necessary, because Virginia’s increase in population did not solve the labor problem of the planters. When servants became free, they preferred to work for themselves even though that might mean going into partnership for a term with one or more other freedmen. And they had been able to set up for themselves because of the cheap public land that was another feature of Virginia society.

Before the middle of the century, while the heavy death rate continued, the men who survived their terms of servitude and managed to set up households of their own were too few in number to offer serious competition to their former masters or to invite systematic exploitation. As they began to live longer, however, as more became free each year, their very numbers posed a problem for the men who had brought them. If the ex-servants continued as freemen to make tobacco, though they would automatically contribute to the fees and duties levied on the trade, they would be competing with their former masters. By adding to the volume of the crop, they would help to depress the price. If they did not make tobacco but lapsed into an idle, perhaps dissolute life such as many had led in England, they would corrupt the labor force and contribute nothing to the revenue derived from the colony. As things were going then, the increasing number of freedmen, whether diligent or delinquent, would increasingly cut into their former masters’ profits.

In efforts to handle this problem, the men who ran Virginia began to alter their society in ways that curtailed and threatened the independence of the small freeman and worsened the lot of the servant. During the last thirty or forty years of the seventeenth century, while tobacco was enriching the king and so many others, most of the men who worked in the fields were losers, and they did not much like it.

One approach to the problem of increasing freedmen was to impose as long a servitude as possible before allowing men to become free. During the extra years of service they would create profits rather than competition for their masters, who would also be able to keep them out of mischief. Servants who came to the colony without an indenture in which the terms were specified were vulnerable to such a move. In 1642 the assembly had prescribed that they could be kept for four years if over twenty at the time of arrival, for five years if between twelve and twenty, and for seven years if under twelve. Between 1658 and 1666 the assembly, as always a collection of masters, revised the terms to give themselves and other masters a longer hold on their imported labor. Henceforth persons nineteen or over when they arrived would serve five years, and persons under nineteen would serve until they were twenty-four.1 The new law meant that most servants who came without an indenture had to serve three additional years, because most of them were in their teens. In fact, so far as surviving records show, most were not over sixteen. The laws required that a master who imported a servant without an indenture bring him to court within six months to have his age determined and his consequent term of service recorded. In the Lancaster records from 1662 to 1680 only 32 of 296 servants were judged to be nineteen years of age or more. The median age was sixteen, and 133 were younger than that and therefore had nine years or more to serve.2 In Norfolk County in the same period only one of 72 servants was judged to be as old as nineteen, and the median fell between fifteen and sixteen.3

Another way to prolong the term of service was to attach greater penalities to the servants’ favorite vice, running away. Early laws had already provided that servants who ran away should have their terms of service extended by double the length of time in which they absented themselves.4 In 1669 and 1670 new laws provided rewards to anyone apprehending a runaway, with the provision that the servant not only reimburse his master by double service for the time missed, but that he also reimburse the public by serving further time at the rate of four months for every 200 pounds of tobacco expended on the reward for apprehending him.5 The rate thus set for reimbursement was about half the current wage for hired labor. In practice the courts sometimes set more equitable rates but they favored masters by allowing the high recovery charges usually claimed by a man who pursued and caught his own servant. In addition to requiring the servant to reimburse those charges by longer service, the courts added time to the servant’s term for presumed losses incurred by the master as a result of the servant’s absence from his job. Though in past decades the provision for double service had ordinarily been considered adequate recompense for crop losses incurred by the servant’s absence, the courts in some counties in the 1670s began adding time, above and beyond double service, for the loss of crop. Thus in Lancaster, Christopher Adams, absent for six months, was required to serve three years extra: one year for the six months’ absence, one year for the loss of the crop that he would otherwise have made, and one year for 1,300 pounds of tobacco expended in recovering him.6 James Gray, absent 22 days, got fifteen months’ extra service: three months for 22 days and loss of crop, and twelve months for the cost of recovery.7 Three servants absent for 34 days were required to serve 68 days for the 34, eight months for the loss of crop, and four months, ten days for the cost of recovery.8

Servants who engaged in forbidden pleasures also had their terms extended. A maidservant who had a child served two years extra for it. And the surreptitious feast in the forest with which servants sometimes indulged themselves became yet another means of extending their terms. The penalty for killing a hog was 1,000 pounds of tobacco or a year’s service to the owner and 1,000 pounds or a year’s service to the informer.9 If the owner and the informer were the same man, as was often the case, he got both. Thus Richard Higby was required to serve his master six years extra for killing three hogs.10

In spite of such legal contrivances for prolonging servitude, men did become free. When they did, they looked for land of their own. With land of their own they could begin to reap the profits that their labors had hitherto earned for others. But in their need for land lay another means of controlling them and extracting a part of their earnings. In the early years few Virginians had thought it worth the trouble to acquire large tracts of land, and men who became free in the first half of the century probably had no trouble finding good land still unclaimed on the James or York rivers or their tributaries. But as life expectancy rose, the expectancy of land-ownership rose with it, and anyone could see that the demand would send land values up. It would be worthwhile to acquire land not merely for future use or to hand on to children and grandchildren, but also to sell or to rent to the rising body of new freemen. In this way the established planters might continue to share in the fruits of their former servants’ labors.

In the Old World, by controlling access to the soil, landlords had been able for centuries to exact a portion of other men’s earnings in the form of rents.11 In Virginia the method could not be as effective as in Europe, because land was too plentiful. But because it was so plentiful and so cheap, it could be acquired in much larger amounts than European landlords aspired to, in amounts large enough to place most of Virginia’s river lands in private hands long before actual settlers reached them.

It was not very costly to acquire large holdings. The head-rights on the basis of which public land could be claimed were bought and sold in Virginia separately from the servants for whose transportation they were issued. Headrights were valid whether the person in whose name they were claimed was alive or dead. The years of heavy mortality, when land was scarcely worth patenting, had left Virginians with a large reservoir of unused headrights. In the 1650s they could be bought for 40 or 50 pounds of tobacco apiece, each headright entitling the owner to fifty acres of land.12

As mortality fell and population rose, Virginians who had a little capital to spare began to assemble headrights and were soon scrambling to patent the colony’s best remaining lands. By the time the land boom began, the best acres were already gone along the lower reaches of the James and York and much of the Rappahannock. Speculators began at once to reach for the plums in more remote areas, including the Potomac region. In 1650 Virginians were just beginning to patent land on their side of the Potomac, where Northumberland County had been formed in 1648. By 1651 they were already staking out claims as far up as Potomac Creek, eighty miles upriver. By 1654 Westmoreland County had been formed, and they were acquiring land along the tributary Occoquan and the Potomac “freshes” in the future counties of Stafford and Prince William.13 Much of the speculative fever centered in Charles City County, where Howell Price, clerk of the court, seems to have served as a broker to speculators. Between 1655 and 1659 he bought up headrights worth 38,500 acres, most of which he sold to other men, who used them to patent land on the Potomac.14 Before the decade was out, a few individuals held title to most of the land on the Virginia side downstream from the present site of Alexandria. A mere scanning of the patents reveals over 100,000 acres held by only thirty persons.15

During the 1650s speculators were also patenting huge tracts on the upper York and Rappahannock rivers,16 and the boom did not stop there. In 1664 the number of headrights used reached the peak of the century, when 3,243 rights were expended on 162,150 acres. In Accomack County alone Colonel Edmund Scarburgh presented certificates for 191 headrights and got 9,550 acres; John Savage got 9,000, and eleven other persons 15,200 acres. And in 1666 eight patents accounted for 34,600 acres (in Rappahannock, Isle of Wight, and Accomack).17 Altogether in the years 1650 to 1675 Virginians patented 2,350,000 acres, more than half the total for the whole period 1635–99.18

After securing a patent, the owner was supposed to “seat” the land, that is, build a house and plant corn or tobacco. He was also supposed to pay annual quitrents to the king at the rate of two shillings for every hundred acres. But until late in the century the quitrents were only sporadically collected, and according to Edward Randolph, an English revenue agent, the way the planters seated the land was to “cut down a few trees and make therewith a little Hut, covering it with the bark and turn two or three hogs into the woods by it: Or else they are to clear one Acre of that land, and to plant and tend it one year: But they fell twenty or thirty trees, and put a little Indian Corn in the ground among them as they lye, and sometimes make a beginning to fence it, but take no care of their Crop, nor make any further use of their land.”19

Such a procedure sufficed to establish a man’s claim to a tract, however large. As a result, the land still appeared to visitors to be “one continued wood.” John Clayton in 1684 observed that “every one covets so much and there is such vast extent of land that they spread so far they cannot manage well a hundredth part of what they have.”20

Managed or not, the acres were owned. And the servants who became free after 1660 found it increasingly difficult to locate workable land that was not already claimed. In order to set up their own households in this vast and unpeopled country, they frequently had to rent or else move to the frontiers, where they came into conflict with the Indians.21 Many preferred safety in the settled area even though it meant renting land from the big men who owned it. In turning down a proposal to levy taxes on land instead of polls, the House of Burgesses in 1663 argued that this would properly entail limiting the right to vote to landholders. And such a limitation would be resented by “the other freemen who are the more in number.”22 Thus the burgesses implied that the majority of freemen were without land. This was probably an exaggeration, perhaps motivated by the realization of burgesses with very large landholdings that they would have to pay more in taxes on their acres than on their servants’ polls. In 1676, however, Thomas Ludwell and Robert Smith, two members of the council, maintained that at least one-fourth of the population consisted of “merchants and single freemen and such others as have noe land.”23 And in the same year Francis Moryson, another former council member, explained the term “freedmen,” as used in Virginia, to mean “persons without house and land,” implying that this was the normal condition of servants who had attained freedom.24 In any case, land had been so engrossed by this time that newcomers, even with substantial capital and a supply of servants, often rented. In 1678, when the Privy Council instructed the governor to confine voting in the colony to landholders, Thomas Ludwell (the secretary of the colony) objected that this would create inequities, because of “many tennants here (especially in James River which hath been longest planted) haveing more tythable servants then their landlords.”25

There are no records from which we can estimate the exact proportion of tenants and owners at any time in the seventeenth century. But there is evidence that in Surry there were 266 resident owners of land in 1704, and 422 households in 1703.26 Thus approximately 156 (37 percent) of the householders appear to have been tenants. The earliest date for which it is possible to make comparison of landowners and householders in exactly the same year is in 1720, in Christ Church Parish, Lancaster County. There, out of 146 householders, 86 were owners, and the other 60 (41 percent) apparently tenants (including several who held large numbers of tithables).27

How large a share of a tenant’s produce did the landlord get? That varied greatly according to the location and quality of the land. In Surry a 300-acre tract described as poor was worth 350 pounds of tobacco a year in 1673; a 100-acre tract rented in 1656 for a barrel of Indian corn (worth about 100 pounds of tobacco).28 In each of these cases the tenant was also to plant an orchard and build or maintain a tenantable house, to be left on the plantation at the termination of the lease (a common requirement). In Henrico County in 1686 a plantation was rented at 100 pounds per year for every person working on it.29 In Lancaster, where land was richer than in Henrico or Surry, a plantation of 100 acres was leased in 1664 for ten years at 60 shillings (about 600 pounds of tobacco) a year for the first two years and 50 shillings (500 pounds) thereafter.30 One man’s crop in Lancaster was almost certainly larger and more valuable than the yield from the cheap lands of Surry. But 2,000 pounds would probably have been a good crop even in Lancaster.31 Hence the rent of a plantation ran from perhaps 5 to 8 percent to 25 percent or more of the annual produce of a single man. Since a plantation, unless it was exceptionally small, would support more than one man, the rent was not high, but it usually represented a good profit for the owner above the quitrent he owed to the king. Moreover, many owners saved themselves this expense by making their tenants responsible for the quitrent.

Perhaps more important than the actual rent obtained by Virginia’s landlords was the effect of the artificial scarcity of land in keeping freedmen available for hire. If a man could not get land without paying rent for it, he might be obliged to go back to work for another man simply to stay alive. The pressure to do so would of course be stronger if he entered on his freedom without tools, clothes, or provisions. According to the “custom of the country” (legally enforceable), a master was required to furnish a servant at the end of his term with freedom dues of three barrels of corn and a suit of clothes (probably worth 500 to 600 pounds of tobacco). But as freedom time drew near, it was tempting to both parties to strike a bargain in which the servant gave up his freedom dues in return for an early release. If his term expired in the slack season from December to May, his labor during the last few months would be worth a good deal less than his dues, perhaps less than his board. But, impatient for immediate freedom or intimidated by an overbearing master, servants often did give up their freedom dues and thus found themselves very quickly back at work for their bread in another man’s household.32

Those who did make it into the ranks of the householders, whether by renting or buying land or staking out a new claim in the interior, faced yet another drain on their earnings. Though it required no more than a piece of land, a hoe, an axe, a few barrels of corn, and a strong back to set up a tobacco plantation, marketing a small crop could be difficult. If a man’s land was on a river or creek, one of the ships that rode in the great rivers from November to June would send hands to roll the hogsheads to the shore and hoist them aboard a boat or small sloop.33 But the prices offered for tobacco varied greatly from year to year, and so did the availability of ships to carry it. A big man with labor to grow tobacco on a large scale could command more attention and better prices from the ships, because his large crop made it possible for a ship to load rapidly and get back to England for a more favorable market than later ships. It was often easier for a small man to sell his crop to his larger neighbor than to gamble on the chance of getting it aboard a ship himself. If his land did not abut a river, he might have no choice but to sell to someone who could get it aboard for him.

The larger planters in this way came to be merchants—many described themselves as such. Some made regular trips to London in order to market a shipload at a time. And, as always, the man who marketed the crop generally made more from it than the man who grew it. Virginians often spoke bitterly about the low prices that the London merchants paid them, but the local Virginia merchant planters could play the same role toward their small neighbors that the London merchants played toward them.34 And as it became common for Virginia’s big planters to be heavily indebted to London merchants, so the small planter became indebted to his larger neighbor. His crop in one year might not buy the clothes and other supplies he needed for the next. The merchant planter would advance the goods against the next year’s crop. And as the London merchants charged Virginia debtors premium prices for goods purchased on credit, it is altogether probable that local debts produced the same advantage to the creditor. To be sure, most creditors were also debtors. In seventeenth-century Virginia, as elsewhere and always, debt was not merely an unfortunate condition to which the poor were subject. Fortunes can often be made by going into debt on a large scale, and the whole Virginia economy was based on credit, often supported by little more than the promise of next year’s crop. Nevertheless, for a man without servants, whose next year’s crop would be the result only of his own labor, debt might be a road back to servitude. When a man could not pay up at harvest time, and there was no good prospect he ever would be able to on his own, when he had no cattle, no land, and not even a feather bed35 to his name, or when these had already all been attached for debt, he might be required to work out his indebtedness by a term of service to his creditor or to someone else who would discharge the debt. In the early 1660s, when tobacco prices were low, one Virginian estimated that three-fourths of the planters were so poor they would have to become servants to the others, “who being merchants as well as planters will bee better able to subsist.”36

It was doubtless an exaggeration to place three-fourths of the population in so desperate a condition. But it seems plain that by the 1660s Virginia was acquiring a new social structure. Outside the structure entirely were the remaining tributary Indians, segregated in what amounted to reservations, beyond the limits of settlement but rightly uneasy about their future. Inside the structure at the bottom were a number of slaves, perhaps more than a thousand but still a minor component of society. A little above them were a much more numerous body of servants, working out the terms assigned them or agreed upon by indenture to repay the cost of their transportation. At the other end, at the top of the scale stood the elite group of men who had inherited, amassed, or arrived in the colony with estates large enough to assure them a continuing supply of servants and to win them lucrative government offices. A little below them were the other established householders, usually with one or more servants. In between the established householders and the servants working out their terms stood the part of the population that had begun to grow most rapidly: the freedmen who had finished their terms of service. They were entitled to set up households of their own, but they were finding it harder to do than the men who became free in the preceding decades.

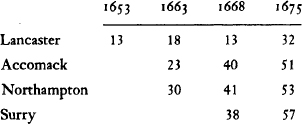

From the annual lists of tithables that survive for four counties it is possible to form some estimate of the ability of freedmen to enter the ranks of householders. The most conspicuous change observable in the lists during the third quarter of the century is the increasing number of households containing only one tithable, that is, one male over fifteen years old.

Percent of Households with Only One Tithable37

Although some of the new one-man households were doubtless headed by the sons of older families who had married and set up for themselves or by new immigrants who had come on their own, the majority probably consisted of men, with or without wives, who had formerly been servants. The increase in one-man households would seem to indicate that the freedmen were doing well, but if we dig a little deeper, a slightly different picture is uncovered. In Lancaster, of 247 servants who either are known to have become free or were legally entitled to freedom between 1662 and 1678, only 24 show up as householders by 1679 (after that date the lists are incomplete because of damage to the records).38 Lancaster in the seventeenth century was a rich man’s county, in the area between the York and the Potomac, where population and tobacco production were expanding most rapidly. But the figures suggest that it was not a land of opportunity for its newly freed servants.

Northampton County, on the Eastern Shore, was a poorer region, but even there, although a servant might make it into the ranks of householders, the odds were against it. From 1664 to 1677, of 808 non-householders who appear on any of the Northampton tithable lists, only 230 later appear as householders; and 88 men who appear as householders later appear as non-householders. Those who lost status, with a few known exceptions, were presumably freemen who had set up on their own and then had to give up and go back to work for someone else. Only 80 of the 329 white non-householders present in the years 1664–67 were still in the county in 1677; 49 of them had become householders, but 31 had still not made it.39

The tithable lists of Northampton and Lancaster argue that Virginia in the 1660s and 1670s furnished fewer opportunities to the poor than either we or seventeenth-century Englishmen may have supposed. A man who came to Virginia with nothing but the shirt on his back expected several years of servitude, but after that he expected something more of life in the New World. When he got to Virginia, however, he found that he might never make it out of the ranks of servants. If he did, it was not likely to be in one of the counties where rich land would insure him success. Land was still abundant but no longer free, except in areas where the danger from Indians or the lack of transportation for tobacco made it uninviting. Those who managed to set up on their own were likely to find themselves still paying tribute to their former masters in the form of rent, not to mention the tribute they paid in yearly poll taxes, export taxes, and fees, as well as the tribute exacted by the king in customs duties at London. Under the circumstances it is not surprising that Virginia’s freemen in these years were reputedly an unruly and discontented lot of men.

The distribution of discontent in Virginia, like the distribution of spoils, was uneven. Geographically the gravest concentrations of unhappiness and unruliness lay probably in the counties that attracted the largest numbers of new freemen. These were not necessarily the most rapidly growing areas. The rich counties on the lower York, Rappahannock, and Potomac were growing very rapidly during most of the second half of the seventeenth century, but they probably grew by the importation of increasing numbers of servants who, when freed, moved elsewhere, perhaps after hiring out for a time to gain capital to set up for themselves in some corner of Virginia less engrossed by the wealthy.

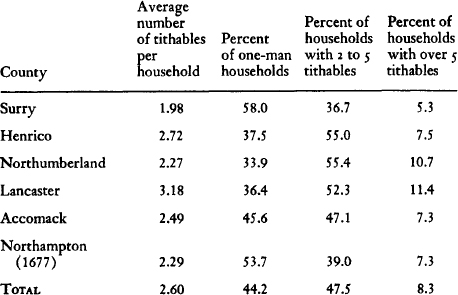

Although it is impossible to tell where the freemen of any county came from, two areas seem for a variety of reasons to have drawn a larger than average number of small planters. The first was New Kent, extending from the upper reaches of the Chickahominy, which empties into the James, to those of the Pianketank, which empties into Chesapeake Bay (see map, page vi) and embracing the various branches of the Mattapony and Pamunkey. The second was the “Southside,” the counties of Surry, Isle of Wight, Nansemond, and Norfolk, along the south bank of the James River. The table of one-man households shows the Southside county of Surry with the largest percentage by 1675 and Lancaster, in the Northern Neck, with the smallest. For one year, 1679, the records allow us to determine the size of households in two additional counties, Northumberland (another Northern Neck county) and Henrico (at the head of the James, embracing both sides). Again Surry appears to be the poorest, not only in having the largest percentage of one-man households and the smallest percentage with more than five tithables, but also in the number of tithables per household, a related but not identical index of wealth.40

Tithables per Household in 1679

No figures are available for the other Southside counties or for New Kent during the seventeenth century, but for the year 1704 it is possible to determine the number of tithables per landowner in all the counties south of the Rappahannock.41 Though this is a less reliable index of wealth than the number of tithables per household, it is the best we have. In 1704 both New Kent and the Southside counties averaged 3 tithables per landowner, while the other counties averaged 4.5. Since we know Surry was in a comparable position thirty years earlier, it seems likely that the other Southside counties were too. As for New Kent, we may perhaps find a clue in the fact that well-to-do residents of nearby counties in the 1670s designated the New Kenters as “rabble.”42

Another clue that New Kent and the Southside counties held a smaller than normal proportion of prosperous planters is the fact that few men from these areas were appointed to the governor’s council. In spite of New Kent’s proximity to Jamestown (a prime consideration in appointments to the council), only one resident of New Kent sat on the council before 1676. More distant counties supplied several members: before 1676 there were three from Rappahannock, three from Westmoreland, five from Lancaster, two from Middlesex, and two from Northampton, all considerably more remote from Jamestown than New Kent. The Southside counties were apparently not as lacking as New Kent in men of sufficient stature to sit on the council, but they too were less well represented than their proximity to Jamestown would have warranted. In the period before 1676 Surry furnished two members and Isle of Wight only one, Nansemond five and Norfolk three. By contrast the counties of York, James City, and Charles City, lying just across the river, furnished sixteen, sixteen, and eight, respectively.43

If the Southside and New Kent had many small householders living on the edge of subsistence, the distress occasioned by low tobacco prices and profit-hungry officials and merchants would have been particularly keen in these two areas. And it would have been made worse by the fact that they both faced more acutely than most other areas a problem that was never far from the consciousness of all seventeenth-century Virginians: the Indians. An act of the assembly in 1669, which specifies the numbers of warriors or “bowmen” in the various neighboring tribes, also indicates the county to which each tribe was adjacent. Of 725 warriors in 19 tribes, 280 in 6 tribes were adjacent to Nansemond, Surry, and Charles City (the southern part), and 200 in 5 tribes were adjacent to New Kent. Of the remainder Henrico accounted for only 40 and the counties on the Rappahannock and Potomac for 190.44

These were all supposedly peaceful Indians, defeated in war and pushed back from the coast. That discontented freedmen and displaced Indians should have been concentrated in the same areas was scarcely accidental. Both were losers in the contest for the richer lands of the tidewater. And both held an uncertain place in the way of life that was developing in Virginia.

If Berkeley’s schemes for Virginia had been successful, both might have had a different future. In keeping with his vision, Berkeley had urged a shift from poll taxes to land taxes, a move that would have reduced the large accumulations held for speculation and that would at the same time have reduced the pressure on the Indians. Berkeley’s whole drive to free Virginia from dependence on tobacco, like Sir Edwin Sandys’ forty years earlier, was accompanied by a consistent effort to find a modus vivendi with Virginia’s Indians.

Not that the governor was a lover of Indians. He had earned his popularity in the colony by subduing them after their last concerted assault on the settlers in the 1640s. In the treaty made in 1646 he had established the ascendancy of the English once and for all, by prescribing boundaries within which the Indians were not to enter without permission (all the tidewater from the York River to the Blackwater, south of the James). As a symbol of their submission the Indians thereafter paid him a yearly tribute of twenty beaver skins and selected their rulers only with his approval.45

Responding to the demands of the expanding English population, Berkeley almost immediately allowed the opening up of the tidewater north of the York, but he clung to the policy of keeping Virginia’s Indians as tributaries rather than enemies, specifically requiring them to assist the colony against any “strange” Indians.46 Other governors followed the same policy during the interregnum of the 1650s, and for a time Virginians even made efforts to convert the Indians to a more English mode of existence. Protection of their title to land, it was felt, would make them think twice about forfeiting it in rebellions. Since they were good hunters, they were offered bounties on wolves (though less than those paid to Englishmen) in the form of a cow for every eight wolves’ heads they brought in. Possession of a cow was expected to serve as “a step to civilizing them and to making them Christians.” They were also invited to send their children into English homes to be brought up as Christians, and were assured that the children would be treated as other servants and not be enslaved.47

But the Indians mostly refused to send their children for lessons in servility, and the cows proved no more successful as missionaries than the few ministers who tried their hand at it. The Indians were more assiduous in growing corn than the English; and cattle, whether their own or the English, only created fencing problems for them. They already practiced an economy that was more self-sufficient and more diversified than that of the English and a way of life that was more urban, if not more urbane. They were the only Virginians who did in fact live in towns, using the surrounding land for their cornfields as well as for hunting and gathering. They needed a good deal of space for these activities but not nearly as much as the thousands of acres claimed by Virginia’s new land barons.

As the English population swelled, and the two economies came increasingly in contact, they did not mesh. Berkeley’s land tax had been rejected by a House of Burgesses loaded with aspiring speculators. The new freedmen were multiplying in numbers every year, and, unable to afford land elsewhere, moved to the frontiers, where they viewed the Indians not as fellow victims but as rivals for the marginal lands to which both had been driven. They brought their cows and hogs with them; they brought their guns; and they brought a smoldering resentment, which they had been unable to take out on their betters. The Indians, they had been taught (if they needed teaching), were not their betters.

The government itself had taught them in the very measures by which it attempted to protect Indian rights. To the Indians who participated in the peace of 1646, the remnants of the old Powhatan confederacy, Virginia conceded that they should not be killed simply for trespassing on the lands that had been taken from them, but only for committing “what would be felony in an Englishman.” The felony was to be proved by “two oathes at least.”48 But the act did not say where or to whom the oaths must be sworn or who was entitled to do the killing once the oaths were taken. Perhaps it was intended that the facts be proved in court, but the act did not say so. When an Indian damaged an Englishman’s property, the law required the victim to seek satisfaction from the Indian’s king and not attempt to recover his losses in the customary frontiersman’s do-it-yourself manner. But in applying this procedure the government displayed a contempt for the rights of individuals that would have been unthinkable in the treatment of any European. When John Powell complained to the assembly about damages done him by Indians in Northumberland, the commissioners of the county were empowered to determine the value of the damage and, after due notice to the “cheife man or men among those Indians,” to seize enough of them to satisfy the award by selling them “into a for-raigne countrey.”49

Perhaps these were foreign or “northern” Indians, who had not participated in the peace of 1646 or had not subsequently been reduced to tributary status, but the measure so casually recorded for enslaving them speaks volumes about prevailing attitudes. Berkeley himself proposed all-out war on the northern Indians. In June, 1666, he told Major General Robert Smith of Rappahannock, “I thinke it is necessary to Destroy all these Northern Indians.” To do so would serve as “a great Terror and Example and Instruction to all other Indians.” Moreover, an expedition against them would pay for itself, for Berkeley proposed to spare the women and children and sell them. There were enough, he thought, to defray the whole cost.50

Thus even Berkeley seems to have thought it appropriate that hostile Indians be enslaved. The standard justification of slavery in the seventeenth century was that captives taken in war had forfeited their lives and might be enslaved. Yet Englishmen did not think of enslaving prisoners in European wars. And it is inconceivable that a raid, say by the Dutch, would have resulted in authorization to seize a suitable number of Dutch men, women, or children for sale into slavery. There was something different about the Indians. Whatever the particular nation or tribe or group they belonged to, they were not civil, not Christian, perhaps not quite human in the way that white Christian Europeans were. It was no good trying to give them a stake in society—they stood outside society. Even when enslaved, it was best to sell them into a foreign country. If the freedman on the frontier failed to discriminate between good Indians and bad, or between Virginia Indians and foreign Indians, if he looked upon all Indians as creatures beneath the rights of Englishmen, if he took potshots at any he saw near his plantation, he would find many of his betters in the House of Burgesses to support him.

In the end, Virginia’s way of life would be reshaped by the freedmen and their betters, joined in systematic oppression of men who seemed not quite human. But before that alliance was devised, Englishmen continued to oppress Englishmen, and the men at the top allowed the discontent of the men at the bottom, in New Kent and the Southside, to reach the point of rebellion. Once rebellion began, there was enough discontent in the rest of Virginia to bring the whole colony to a boil.

1 Hening, I, 257, 443; II, 113, 240.

2 Lancaster III and IV, passim.

3 Norfolk IV, VI, and VII, passim.

4 Hening, I, 254, 401, 440.

5 Hening, II, 273–4, 277–79.

6 Lancaster IV, 161.

7 Ibid., 163.

8 Ibid., 263.

9 Hening, II, 129 (1662). In 1679 the assembly provided further that second offenders should have their ears nailed to the pillory and then cut off, and that third offenders be treated as felons under English law, i.e., be subject to the death penalty. Hening, II, 440–41.

10 Lancaster IV, 142.

11 It has been argued that in times and places where land was abundant and rents consequently low, as in early America and in late sixteenth- and early seventeenth-century Russia, the result was to make entrepreneurial classes develop some form of serfdom or slavery. Evsey D. Domar, “The Causes of Slavery or Serfdom: A Hypothesis,” Journal of Economic History, XX (1970), 18–32. The hypothesis would seem to be borne out by the developments under way in seventeenth-century Virginia.

12 Norfolk III, 205a; Westmoreland I, 51.

13 VMHB, XXIII (1915), 249–50; Hening, I, 351–53, 381; Nell M. Nugent, Cavaliers and Pioneers: Abstracts of Virginia Land Patents and Grants (Richmond, 1934), 185–316.

14 Fleet, Virginia Colonial Abstracts, X, 29, 33, 39, 46, 53, 64, 78, 84, 88, 91, 101; XI, 27, 33, 74. The names of the persons for whom headrights were claimed were usually certified by a county court and copied in its records. The rights could then be sold, as Price sold his, and the person ultimately exercising the rights would then record the names again in the patent he obtained. It is thus possible to trace, through the excellent index in Nugent’s Cavaliers and Pioneers, the ultimate use made of Price’s certificates. He seems to have exercised rights to only 1,000 acres himself.

15 Nugent, Cavaliers and Pioneers, 185–390. Some of the larger patentees were John Wood, 10,000 acres; Samuel Mathews, 5,200; Gervase Dodson, 11,400; Thomas Wilkinson, 6,500; Henry Corbin, 3,900; Giles Brent, 6,000; and Nathaniel Pope, 5,100.

16 Ibid., 194–96, 200, 244–45, 324.

17 Ibid., 424–524, 548–61.

18 Craven, White, Red, and Black, 15–16.

19 C.O. 5/1309, No. 5. Aug. 31, 1696.

20 Sloane Mss. 1008, ff.334–35.

21 C.O. 1/39, f.196; Massachusetts Historical Society, Collections, 4th ser., IX (1871), 164.

22 George Bancroft, History of the United States, 15th ed. (Boston, 1856), II, 207, quoting from “Richmond Records, no. 2, 1660 to 1664, p. 175.” (These records were destroyed in the burning of Richmond in 1865.) John Daly Burk, who also had access to the destroyed records, says of the proposed change: “The attempt probably originated in a desire of contracting the right of suffrage, in order as it was pretended that the poorer classes might not have it in their power to elect to the assembly men disaffected to the government.” The History of Virginia, from Its First Settlement to the Present Day (Petersburg, 1804–16), II, 137.

23 Coventry Papers, LXXVII, 128.

24 Ibid., 204.

25 Ibid., LXXVIII, 202.

26 The first extant quitrent roll, showing the owners of land, dates from 1704 and is reproduced in Thomas J. Wertenbaker, The Planters of Colonial Virginia (Princeton, 1922), 183–247. The only county in which the number of households is known at about that time is Surry, where the tithable lists exist for the year 1703. Surry V, 287–91. Kelly, “Economic and Social Development of Surry County,” 124, says that the 1703 tithable list shows a total of 462 freemen in that year. Such a number is not incompatible with the total of 422 households listed, but it is not clear how Kelly has identified freemen living in other men’s households. From recorded deeds and land patents Kelly estimates that in the last thirty years of the seventeenth century over 40 percent of Surry’s freemen were non-landowners (p. 125).

27 Thirty-eight (31 percent) of the 124 landowners on the rent roll were apparently non-resident. The list of tithables is in Lancaster IX, 335–36; the rent roll is in the Virginia State Library.

28 Surry I, 151–52; II, 24.

29 Henrico II, 127.

30 Lancaster II, 285. These are only samples of numerous leases recorded in the court records of various counties. More are cited in Bruce, Economic History, II, 413–18.

31 See chap. 7, note 33.

32 The three barrels of corn were worth about 300 pounds of tobacco. On the value of the clothes given as freedom dues see chap. 17, note 16. In 1677 the assembly limited the right of masters to make bargains with their servants, “especially some small tyme before the expiration of their tyme of service.” Hening, II, 388.

33 It is difficult to determine how hogsheads were loaded in the seventeenth century, but Hugh Jones in 1724 said that it had been the custom “in some places” for sailors to roll the hogsheads, sometimes for some miles. Jones, The Present State of Virginia, Richard L. Morton, ed. (Chapel Hill, N.C., 1956), 89. Thomas Adams in a letter to the London merchants Perkins, Buchanan, and Brown, April, 1770, says it had always been the custom for the buyer to pay the cost of getting tobacco aboard ship, though not to take the risk of loss in the process. VMHB, XXIII (1915), 54–55. One case that reached the Northampton County court in 1652 shows a ship captain hiring a man with a shallop to get tobacco aboard. Northampton IV, 88.

34 Aubrey C. Land has emphasized the entrepreneurial activities of the Chesapeake merchant planters in the eighteenth century. “Economic Behavior in a Planting Society: The Eighteenth-Century Chesapeake,” Journal of Southern History, XXXIII (1967), 469–85. The behavior he describes was characteristic of seventeenth-century planters also, though on a smaller scale.

35 Feather beds were a highly valued item in Virginia, being listed in inventories for 400–600 pounds of tobacco, about the same value as a cow. One of Governor Berkeley’s enemies, complaining of Virginia tax levies, accused Berkeley of saying that if people “had not tobacco they had cowes and fetherbeds sufficient to discharge their leavies.” Coventry Papers, LXXVII, 144.

36 Ms. Rawlinson A 38, Bodleian Library, Oxford.

37 The first year in which a figure appears is the first year in which a record is available for that county. The total number of households in each county was as follows: Lancaster had 92 in 1653, 175 in 1663, 191 in 1668, and 196 in 1675; Accomack had 128 in 1663, 188 in 1668, and 297 in 1675; Northampton had 151 in 1663, 177 in 1668, and 205 in 1675; Surry had 182 in 1668 and 245 in 1675. Lancaster in 1653 included the future counties of Rappahannock (1657) and Middlesex (1669). The figures are from Lancaster I, 90; III, 234–38; IV, 85–87, 335–38; Accomack I, 35; II, 80; V, 326; Northampton VIII, 175–76; X, 54–55; XIII, 73–75; Surry I, 315–17; II, 92–94.

38 205 servants who had their ages judged before 1678 were to become free by that year. An additional 42 of unstated age received their freedom by court order after suing for it. Lancaster III and IV, passim.

39 See Appendix, pp. 423–31, where the Northampton lists are analyzed in detail. The figures that follow are derived from that analysis.

40 The Surry, Lancaster, and Accomack lists are part of the annual listing of tithables in those counties and are in Surry II, 225–27; Lancaster IV, 514–17; and Accomack VIII, 99–101. I have also included the Northampton figures for 1677 (from Northampton XII, 189–91) since the year is so close, and no later figures for Northampton survive. The Henrico and North umberland figures derive from a law requiring each county to raise a soldier for every 44 tithables. In calculations made to implement the law in these two counties the court set down the number of tithables in each household. The records are in Henrico I, 102–3, and Northumberland III, 37–38. The number of households in each county was as follows: Surry 226, Henrico 160, Northumberland 289, Lancaster 176, Accomack 274, Northampton 205.

41 The tithable figures are in Evarts B. Greene and Virginia D. Harrington, American Population before the Census of 1790, 149–50. The list of landowners in Wertenbaker, Planters of Colonial Virginia, 183–247, does not include the counties of the Northern Neck, between the Rappahannock and the Potomac.

42 William Sherwood to Sir Joseph Williamson, June 1, 28, 1676; Philip Ludwell to same, June 28, 1676, VMHB I (189–94), 167–85. Note p. 174 for identification with New Kent. See also Massachusetts Historical Society, Collections, 4th ser., IX (1871), 165, 166, 170.

43 Figures drawn from William G. and Mary N. Stanard, The Colonial Virginia Register (Albany, N.Y., 1902).

44 Hening, II, 274–75.

45 Hening, I, 323–26. The treaty of 1646 seems to have required this tribute only from Necotowance, who was evidently the successor of Opechancanough as head of the empire that Powhatan had formed. But by the 1660s that empire had crumbled, and at some point the English began collecting the tribute from each neighboring tribe. A treaty in 1677 spelled out the obligation of “every Indian King and Queen” to pay it. VMHB, XIV (1906–7), 294.

46 Hening, I, 353–54; II, 34, 35, 39, 138–43, 193–94. 218–20; Craven, White, Red, and Black, 58, W. S. Robinson, “Tributary Indians in Colonial Virginia,” VMHB, LXVII (1959), 49–64. See also the letter of Berkeley to the commissioners of the Northampton County court in 1650, warning against taking lands from “the Indyans commonly called by the name of the Laughinge Kinge Indyans” who “have beene ever most faithfull to the English And particularly that neither they nor their Kinge in the last bloody massacry could bee enjoined to engage with our Enemyes against us And soe by consequence kept the remoter Indyans att Least Neutrall….” Northampton III, 207a. Cf. Berkeley to Lancaster commissioners, Dec. 7, 1660. Berkeley Papers, Alderman Library.

47 Hening, 1, 393–96.

48 Ibid., 415.

49 Hening, II, 15–16.

50 WMQ, 2nd ser., XVI (1936), 591.