The aim of this chapter is to chart a number of options for the evolution of consciousness (in a broad sense of that term) with particular attention to how consciousness fits into the genealogical relations between animals represented in the “tree of life.” The evolution of consciousness has been an area of rampant speculation. That speculative quality will remain for some time, but progress in various parts of biology is beginning to give us a more constrained sense of the likely shape of the history, or at least a range of possible shapes. The treatment in this chapter is preliminary and exploratory, though, and often written in a conditional mode: if biological feature X matters to consciousness, then the history of consciousness may have gone like this …

I focus especially on the following questions: Was there one path through which consciousness arose, or more than one? That is, was a single origin followed by radiation down various lines, or were there several independent origins? If there were multiple paths, is this a matter of a single type of path, and several instances or tokens of that type, or was there more than one type?

A second question is related: did consciousness arise in a gradual way, or was there more of a jump or threshold effect? In philosophy, people often talk as if consciousness is either present or absent; there’s something it’s like to be this creature, or there is not. But this may be a matter of degree, either with or without an “absolute zero.”

The issues of gradualism and path number interact. The greater the role for gradual change, the deeper the evolution of consciousness probably goes (the further back a non-zero value probably goes), and hence the greater likelihood of one origin and subsequent radiation.

These questions would have simple answers if only humans, or only primates, were conscious. Then there would probably be a single origin, and radiation down just a few lines. I assume this restriction of the trait is unlikely. Other background assumptions made include materialism, and the assumption that a great many entities have no scrap of consciousness at all – there is an “absolute zero,” and this is a common value. I also assume a mainstream neo-Darwinian form of evolutionary theory. The term “phylogenetic” in my title refers to large-scale historical patterns, especially the genealogical relationships between different kinds of organisms.

My title uses the term “consciousness” in a broad sense now common in the literature. In this sense, if there is “something it’s like” to be an animal, then that animal is conscious (Nagel 1974, Chalmers 1996). I think this is not a helpful terminology. Historically, the term “consciousness” has usually suggested a rich form of experience, not the simple presence of feelings. Confusion arises from the terminological shift, as talk of consciousness in animals inevitably suggests a sophisticated “here I am” state of mind, not just a wash of feeling. Aside from the history of ideas, I expect the eventual shape of a good theory to be one that recognizes a broad category of sentience, something present in many animals, and treats consciousness as a narrower category. That broad-versus-narrow distinction could be marked in various ways, though, and terminology per se does not matter much. So especially when discussing other people’s views, I will use “consciousness” in a broad manner here, only occasionally being more careful with the term.

The next section discusses the evolutionary history of animals. I then lay out some biological and cognitive features that have a prima facie relationship to consciousness, and look at their different evolutionary paths.

The history of life on earth is often said to form the shape of a tree. What is meant is that from a single origin, a series of branching events gave rise to the different forms of life present at later times. The tree model does not fit all forms of life well (bacteria, for example, form a network with a different shape), but this chapter focuses on animals, and the genealogical relationships among animals are indeed tree-like.

Animals originated something like 700–900 million years ago, and comprise a single tree-shaped branch within the total genealogical structure. It is still common, mostly outside of biology, to talk of “higher” and “lower” animals, and of a phylogenetic “scale.” (A person might ask: “where in the phylogenetic scale does consciousness begin?”) This does not make much sense as a way of describing the evolutionary relationships. In a tree, there is “higher and lower” in the sense of earlier and later. But there are lateral relationships as well, and much of what people have in mind when they talk of a phylogenetic scale is not a matter of temporal order. They might intend a distinction between simple and complex, but there are many varieties of complexity (is a bee less complex than an eel?).

Jellyfish, for example, might be called “lower animals,” but present-day jellyfish are the products of as much evolution as we are. There were jellyfish-like animals well before there were human-like animals; present-day jellyfish have relatives much lower (earlier) on the tree who look a fair bit like them, most likely, whereas all our relatives from that time look very different from us. Some of our ancestors might have looked something like jellyfish. But simple animals living now need not resemble ancestors, either of them or of us, and complex earlier forms can have simpler descendents.

So within a tree-based picture of animal life, there is earlier versus later, closer versus further (from us, or someone else), and there are various senses of simple versus complex. None of these match up well with “higher versus lower.”

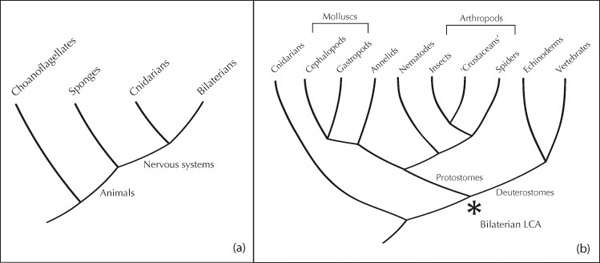

Any two animals alive now have various common ancestors, including a most recent common ancestor, the last one before the evolutionary lines leading to each present-day animal diverged. The shape of the history of animals is shown in Figure 20.1. Among the groups left out of the figure are two problematic ones: ctenophores and placozoans. Ctenophores are also known as “comb jellies,” though they are not really jellyfish. Placozoans are mysterious creeping animals without nervous systems. Nervous systems appear to have evolved early (perhaps 700 million years ago) and are seen in nearly all animals. It is contentious whether nervous systems evolved once or more than once, due especially to uncertainty over the location of ctenophores, which have nervous systems, in relation to sponges and placozoans, which do not. I’ll set those questions aside and look just at the large branch of animals who have nervous systems and are on the right of sponges on Figure 20.1(a). Those are the cnidarians, which include jellyfish, corals, and anemones, and bilaterians – bilaterally symmetrical animals – which include us, fish, birds, octopuses, ants, crabs, and others.

The last common ancestor of bilaterian animals (hereafter, “bilaterian LCA”) lived perhaps 600 million years ago. It was very possibly a small flattened worm, but no fossil record exists of this animal. If the figure of 600 million years ago is right, then the setting for the evolution of this animal is the Ediacaran period (635–540 million years ago), a time when all animals were soft-bodied and marine, probably with very limited behavioral capacities (Peterson et al. 2008, Budd and Jensen 2015). Genetic evidence places many significant branchings in this period. Then, in the Cambrian period (540–485 million years ago), bodies with hard parts appeared – shells, legs, and claws – along with image-forming eyes. Most of the familiar groups of present-day animals have a recognizable fossil record from this time, including arthropods, molluscs, and vertebrates. Predation is also evident from the fossils. Animal life was still entirely marine, though some animals began to move onto land from about 430 million years ago. In a few groups, significant neural and behavioral complexity also arose, especially in vertebrates, arthropods, and one group of molluscs, the cephalopods.

A first rough count might then recognize three independent origins for conspicuously complex nervous systems and behavior. Those origins are independent – in this first count – because the most recent common ancestor of those three groups was probably a simple worm-like animal. In addition, cephalopods acquired their large nervous systems in a process that stemmed from a simple shelled mollusc. Figure 20.1(b) shows the relationships between these groups in more detail (see also Trestman 2013, Farris 2015, Feinberg and Mallatt 2016).

That first count of three origins for complex behavior will be contentious for many reasons. Animals differ in cognitive and behavioral styles, showing many kinds of complexity. There are also lumping-versus-splitting issues. I counted one origin for vertebrates, but mammals and birds are more neurally complex than other vertebrates, including their common ancestor, so you can count two origins within the vertebrates for complex behavior in one reasonable sense. Within the arthropods are several groups with complexity of their own particular kind, not all clustered together. Behaviorally complex spiders, for example, are some distance from behaviorally complex insects such as bees. Still, there is some sense in that first count of three evolutionary lines producing significant neural and behavioral complexity.

Which biological features are relevant to the evolution of subjective experience? There is no consensus on what matters – on what makes the difference between there being, or not being, “something it’s like” to be an animal. This chapter aims at a compromise between covering ideas that have been influential in the literature, exploring directions I think are promising, and discussing options that illuminate evolutionary possibilities. (For a more opinionated treatment, see Godfrey-Smith forthcoming). I’ll begin by looking at a view based on a kind of overall cognitive complexity in animals, and then move to views that posit more specific innovations.

The first option can be motivated by the idea that perhaps what we call “consciousness” is just cognition, the information-processing side of the mind, as seen “from the inside,” though perhaps only cognition that has a certain degree of complexity suffices. As emphasized above, there are different kinds of complexity. But it might be possible to pick out a common element, and a common currency, that get us some purchase on the situation. Many kinds of complexity in how animals handle sensory information and control action can be understood in terms of integration. In some, but not all, animals, the deliverances of many senses are integrated when working out what to do, and this integration might amount to building a kind of “model” of the world. Present experience may also be integrated with earlier experience, by means of memory. Choice of action may be conditioned by motivational tradeoffs – an integrated handling of competing goals. These are all moves away from simple patterns in which a sensed event gives rise to a fixed response.

The idea that integration is pivotal to consciousness figures in several other literatures. An extreme development of the idea is the “Integrated Information Theory” of Tononi and Koch (2015), in which any sort of integration of processing in a system counts – whether or not the system is alive, and whether or not it has senses and controls action. I don’t think that near-panpsychist view is well motivated (2015), but integration might be important in other ways. “Global workspace” theories of consciousness treat the integration of sensory information, and sensory information with memory, as a feature of brain processes associated with consciousness (Baars 1988, Dehaene 2014). Some versions of this view associate integration and the creation of a “workspace” with particular vertebrate-specific brain structures. A more liberal version would see integration of information as achievable in various ways. Far from the usual territory of workspace views, Klein and Barron (2016) argue for the likely presence of consciousness in insects, based on the integrated way they handle sensory information and determine behavior: “Centralization in the service of action selection is … the advance that allowed for the evolution of subjective experience.”

If an approach along these lines were right, it would suggest a gradualist view of the evolution of consciousness. Cognitive complexity of a kind measured by integration shades off into low values, and does so in a way that extends well outside animals. Even some bacteria have a sensorimotor arc that works through a comparison of what is sensed in the present and in the immediate past (Baker et al. 2006).

Dramatic changes occurred in this feature, however, in animal evolution. The invention of the nervous system – with the branching dendrites of neurons ideal for integrating inputs – was a landmark, as was the invention of the bilaterian body plan, which led to the evolution of centralized nervous systems. (Cnidarians have nervous systems but not the centralization associated with a brain.)

In Figure 20.1(b), the bilaterian LCA is marked with an asterisk. The traditional picture of this animal has been that it was small and simple, probably flatworm-like, with little or no neural centralization. The brains of arthropods and vertebrates were seen as independent inventions, without a common design or a mapping from part to part based on common ancestry. Some recent work, though, has posited a richer endowment at this crucial stage. Wolff and Strausfeld (2016) argue that commonalities in layout between arthropod and vertebrate brains show that an “executive brain” was present in their common ancestor. What is meant by “executive brain” is less tendentious than it might sound; the suggestion is that there was some centralization, featuring two circuits that achieve integration in the sense introduced above. One circuit integrates different sensory inputs, and the other enables comparison of present input with the recent past (Strausfeld, personal communication). The quiet years of the Ediacaran may then have seen the origin of a new kind of control device in animals.

Within the view positing an executive brain in early bilaterians, cephalopods become a very special case. The argument for complexity in the bilaterian LCA by Wolff and Strausfeld is based on a comparison of vertebrates and arthropods. Cephalopod brains, they note, are different from both. The resulting picture would be one in which the bilaterian LCA had an executive brain carried forward through arthropod and vertebrate lines, but early molluscs threw this brain away. Cephalopods eventually evolved a new one with a different organization. There would then be two origins for an integrating executive brain, one for cephalopods and one for everyone else who has one.

The first option, which suggested a gradualist view, supposed that consciousness is just the information-processing side of the mind as seen “from the inside,” and the evolution of consciousness tracks the general evolution of cognitive complexity. This has not been the approach generally taken in recent discussions. Instead, the usual aim has been to find one or more specific innovations that are the basis for consciousness. Most researchers accept that even quite complex perception, cognition, and control of action can go on entirely “in the dark” (Milner and Goodale 2005, Dehaene 2014). If “much of what can be done consciously can also be done unconsciously” in the human case (Prinz, Chapter 17 in this volume), it makes it unlikely that the division between conscious and non-conscious across animals is a simple matter of complexity of the nervous system.

Though much work has been guided by this perceived dissociation between cognitive complexity and consciousness, such a view can be challenged even for the human cases that provide the data. Morten Overgaard, for example, argues that a close look at “blindsight,” and related phenomena, shows a tighter relationship between what is experienced and what can be done (Overgaard et al. 2006). I won’t take sides on this debate, and in the rest of the chapter I’ll look at views that isolate specific traits as crucial to consciousness.

The first is a family of views that focus on sensing and perceptual representation. Perhaps what matters to consciousness is a particular kind of processing along a sensory path. Certainly it seems that, for us, subjective experience is brimful of sensory encounter with the world. A theory of consciousness might then be a theory of a specific kind of processing of sensory information – Prinz (Chapter 17 in this volume) defends a view of this kind.

Sensing itself is ubiquitous; it is seen in unicellular organisms and plants as well as animals. If you think sophistication in sensory systems holds the key to consciousness, you could opt for a gradualist view that extended some degree of consciousness outside animals. But there are landmarks in the evolution of sensing that might have special importance. Looking first at sense organs themselves, the Cambrian sees the evolution of image-forming eyes of two kinds, the compound eyes of arthropods and camera eyes of vertebrates. Cephalopods later evolved camera eyes independently. This is the beginning of the sensory presentation of objects in space. Dan-Eric Nilsson’s survey of animal eyes (2013) recognizes just three groups with “Class IV” eyes, high-resolution image-forming eyes: arthropods, vertebrates, and cephalopods, the same three groups picked out at the end of the previous section.

Feinberg and Mallatt (2016) link the evolution of consciousness to the invention of brains that map what is sensed, with spatially organized neural structures. Some animals, and not all, engage in neural processing that is isomorphic to the structure of sensory stimulation. The presence of spatially organized processing of sensory information may indeed be a landmark, though the way Feinberg and Mallatt bring this feature to bear on consciousness has some problems. They say that spatially organized neural structures give rise to mental images. The idea of a mental image is experiential, but the “images” that Feinberg and Mallatt describe neurobiologically are map-like internal structures. Citing the presence of neural “images” in this sense does not itself establish a link to consciousness.

Prinz argues that the special feature distinguishing conscious from unconscious sensing involves how the senses connect to the next stages downstream, through attention and working memory. Attention is a gateway to working memory, and for sensory information to be in attention is for it to be conscious.1 Prinz, in Chapter 17 in this volume, discusses how these traits might be distributed among animals. They are not restricted to mammals. Both are present in birds, and fish can also achieve “trace conditioning,” which involves holding a stimulus “in mind” over a delay. Trace conditioning is both a test for working memory and a form of conditioning with an empirical connection to conscious reportability in humans (Allen, Chapter 38 in this volume). Even some insects have attention and working memory. Cephalopods, for Prinz, are a “maybe.” Put into the phylogenetic structure of Figure 20.1(b), this suggests a view with multiple path tokens and one path type. Consciousness for Prinz has a unified basis – the same package of features have to be present in every case – but the package probably evolved more than once. If cephalopods are included, three path tokens is again a plausible number, unless there was more than one origination event within one or more of those large groups.

Prinz sees attention and working memory as definite inventions, which are either present or not. But both might be seen as shading off into minimal forms (recurrent neural network structures in the case of working memory; any kind of flexible allocation of resources in the case of attention). Then the story would be more gradualist and might push deeper, yielding fewer distinct origins.

I’ll discuss one more view that emphasizes the sensory side, drawing on Merker (2005). If an organism has rich senses and can also move freely, this introduces ambiguity into the origins of sensory stimulation. Was that sensory event due to what I did, or to a change out in the world? In invertebrates, Merker says, this problem tends to be handled peripherally, with a neural patch of some sort, but in vertebrates it motivates the construction of a centralized “model” of the world, with the self as part of the model. Barron and Klein (2016) argue that insects do construct such models in a relevantly similar way to vertebrates, and this feature is indicative of consciousness in both cases.

Either tied to the notion of “world model” or in a more general way, the transition to a form of sensing that includes internalization of a distinction between self and other may be particularly relevant to the evolution of consciousness. Once again, this begins early and in simple forms (Crapse and Sommer 2008); circuitry that handles self/other issues in this way is found even in nematodes, which have only a few hundred neurons. Animals can have this capacity while not having image-forming eyes or similarly sophisticated senses. A version may have been present even in the bilaterian LCA, though this is also a plausible candidate for several independent inventions.

Another candidate for a basic, old form of subjective experience is feelings of the kind that figure in evaluation – feelings marking a distinction between good and bad, welcome and unwelcome. Perhaps the first kind of subjective experience was affective or evaluative? This is a form of experience with a plausible evolutionary rationale (Denton et al. 2009, Damasio and Carvalho 2013).

If we start with the general idea of valuation – treating events as welcome or unwelcome – then we again face the fact that this capacity goes back far in history and reaches far away on the tree. Bacteria and plants are valuers in a broad sense, discriminating welcome from unwelcome events. But as with sensing, there might be some landmark introducing a kind of evaluative processing with plausible links to consciousness.

One way to develop such a view looks at the role of evaluation in learning. This view can be introduced through recent work on pain. “Nociception” – detecting damage and producing an immediate response, such as withdrawal – is very common in animals. Pain as a feeling, with its distinctive aversive quality, is thought to involve something extra. Perhaps the organisms that experience aversive feelings are the ones that can put the detection of unwelcome events to work in rewiring their behavior for later occasions (Allen et al. 2005, Elwood 2012). Pain, on this view, is a teacher for the long term.

This view might be generalized to feelings other than pain. Indeed, pain is a special case, as it has a sensory side that is concerned with (putting it briefly) facts as well as values. “Classical” theories of pain distinguish two neural paths, one tracking locations and varieties of damage (that’s a sting, in my toe …), and another concerned with the unpleasantness of pain (… and it feels very bad). There is “pain affect” as well as “sensory pain experience.” Here we are especially concerned with the affective side. Perhaps the felt side of valuation and reward systems in animals has a general involvement with learning. Animals that cannot learn by tracking aversive and positive experiences would then lack (this kind of) subjective experience.

I don’t know of a theory that makes that claim in a simple and direct way, though some are close. Ginsburg and Jablonka (2007) see associative learning as crucial to the evolution of consciousness, but they have in mind a subset of reward-based learning together with some other kinds, unified by their “open-ended” character (see below). Similarly, Allen et al. (2005) do not argue that all instrumental learning comprises evidence for pain affect, only kinds powerful enough to establish novel behaviors in an individual’s repertoire. I think the claim that learning is the key to consciousness is unlikely to be right. But let’s follow this path some distance, and then look at reasons to modify it.

I’ll use the term “instrumental learning” for learning by tracking the good and bad consequences of actions. This is one of two main kinds of “associative” learning. The other, “classical” conditioning, as seen in Pavlov’s dog, is essentially predictive and need not involve (much) evaluation. One event (a bell) is used as a predictor of another (food). Classical conditioning is very common in bilaterian animals and has been reported (once) in an anemone. (I use here a survey of invertebrate learning by Perry et al. 2013.) The first credible report of classical conditioning in a plant has also just been published (Gagliano et al. 2016). Instrumental learning appears to be rarer. It is scattered through the tree of animals in a way that suggests it may have evolved a number of times. It is seen in vertebrates, in some molluscs (gastropods and cephalopods), and some arthropods. Various insects, especially bees, are good at it, but in some others it has not been seen. The Perry et al. review I rely on here reports cases where the trait has been shown present, and does not make claims about what is absent (which would be harder to do). But the review does list it as unreported in an interesting range of groups, including wasps (which are insects), spiders, myriapods such as millipedes, and starfish.

This sets up an interesting relation between the family of traits discussed in the previous section, concerned with sensing, and those discussed here. Animals can have one while lacking the other, it seems. I’ll discuss that relationship below. First I will look more closely at valuation and learning.

The boundary between instrumental and other kinds of learning does not appear to be sharp, and the boundary between instrumental learning and reward-based behavior of other kinds is not sharp either. Beginning with the second relationship, moment-to-moment guidance of behavior with reward systems is more common than learning through reward. Moment-to-moment guidance of this kind is seen in an animal’s tendency to stay in the area of a rewarding stimulus, or continuing to approach it, in a way that need have no long-term consequences. A wide range of these reward-based behaviors across animals have a common neurochemical basis, in dopamine systems (Barron et al. 2010). Reward-responsive behavior is mediated by dopamine in nematodes, molluscs, and vertebrates – animals whose most recent common ancestor was again the bilaterian LCA. That suggests that dopamine-based reward-guided behavior might have evolved before the Cambrian. Barron et al. (2010) raise this possibility but think it unlikely. Instead, they think that an old role for dopamine, and/or related compounds, in modulating behavior in response to environmental stimuli made them natural raw materials for use in the evolution of genuine reward-based control systems, when they arose in various animals later on.

The view tying feelings to learning is one way of finding an evolutionary landmark distinguishing simple from complex evaluation. But some of the best behavioral evidence for pain in invertebrates involves moment-to-moment reward-based behavior, not long-term change (Elwood 2012). These behaviors show trade-offs between competing goals – hermit crabs will leave shells to avoid electric shock, but better shells will only be relinquished after stronger shocks. Those trade-offs, which need not involve lasting behavioral change, seem powerful evidence for affect in their own right. In reply, it might be noted that these animals can also learn instrumentally. Still, is there reason to think that learning per se is what counts? An alternative view is that learning is standing in here for a general sophistication in the handling of valence in experience, or is one variety of this sophistication among several. Perhaps instrumental learning (or a subset of it) is sufficient but not necessary for the kind of evaluative cognition associated with subjective experience.2 Something that does seem to make sense at this point, though, is the general idea of an evaluative path to consciousness.

Evaluative feelings are plausible early forms of subjective experience. Perceptual states of some kinds are another plausible form. Both have been used in single-factor theories. People also often write as if they go together – as if once you are “conscious,” you are aware of the world and experience things as good or bad. But these two features might come apart; the presence of one does not imply other, and each might have their own role in evolution.

First, it seems possible in principle to have a rich form of evaluation present in an animal that is quite unsophisticated on the sensory side. Such an animal would not be entirely cut off from the world; no animal is. But assuming some distinction between genuine perception and mere sensitivity (Burge 2010), it seems there could be an animal that was richly involved with evaluation and affect, but not in a way that included a sophisticated referral of sensed events to objects in the environment. The organism might lack the ability to track exactly what is going on around it, but have a stronger registration of whether whatever is going on is welcome or unwelcome.

The other separation seems possible as well. There could apparently be an animal that tracked the world with its senses in acute and complex ways, handling the self/other divide in a sophisticated manner, but was much simpler on the evaluative side – an animal more “robotic” in that sense.

In vertebrates, we have both sides – complex sensing and evaluation. The same is seen in octopuses. But other cases might probe the relationship between the two. For example, some land-dwelling arthropods might be examples of perceptually complex animals with much simpler evaluation.

All the cases are uncertain. Some spiders show complex behavior (Jackson and Cross 2011). In Perry et al. (2013), spiders are absent from the list of instrumental learners. Sometimes jumping spiders are reported as instrumental learners, but at best they are an interesting borderline case, given what is known. What has been shown is that during an attempt to catch an individual prey item, a trial-and-error process is used to find a way of deceiving the prey with signals. Successful signals are not (as far as is known) carried over from day to day, and there is no reason why they should be. I said above that I doubt that learning is the crucial element on an evaluative path to consciousness, so I don’t think the absence of learning here need be especially significant, but spiders remain animals where there is an apparently limited role for integrated, non-routine guidance of behavior by evaluative experiences.

Wasps are also listed as classical but not instrumental learners in the Perry et al. review (though I have seen one positive report: Huigens et al. 2009). The category “wasp” does not pick out a definite branch of the phylogenetic tree, as ants and bees are embedded within the same branch, surrounded by various animals with a wasp-like lifestyle.

These sorts of cases give us at least a sense of what to look for, and if arthropods of this kind had rather simple evaluative capacities, that would make ecological sense. Terrestrial arthropods such as wasps often have short lives dominated by routine – by a specific series of behaviors that have to be performed. But these animals can face substantial sensorimotor demands, especially those that can fly.

What about the other side? In the Perry et al. review, gastropods (slugs and snails) are the least mobile animals reported to have shown instrumental learning. What has been found is, as far as I know, very simple forms of this learning, not the discovery and entrenchment of novel behaviors. But they seem a possible case. They have fairly simple eyes (though some do have low-resolution image-forming eyes – Nilsson’s “Class III” eyes) and simple ways of moving (no flight, though some can swim). They may be simple on the sensory side and stronger on the evaluative side: they might have a fairly rich sense of good and bad, but a weaker grip on what exactly is going on in the world.

So there are two traits here that have plausible connections to subjective experience, but they do not look like different paths to the same thing. They lead to different things. Both of them can be summarized with the idea that there is “something it’s like to be” one of those animals, but the evaluative and perceptual forms of this feeling-like-something are different. Animals might gain both features, either one first and then the other, or both at once. They might also stop having gained one, if the second is of little use or precluded for some reason. Are all the sequences equally plausible in principle? Speculatively, I suggest that the evaluation-only and evaluation → perception paths might be less straightforward. Animals may need to have fairly complex behavioral capacities in order for complex evaluation to do them much good, and if they have those complex behavioral capacities, they might need fairly complex sensing as well. The converse does not hold; if your life is short and routinized, then evaluation may remain simple, even if you have complex sensorimotor tasks to deal with. This would make it hard to start with the evaluative form of consciousness and move to the perceptual form, easier to move in the other direction. I raise this asymmetry tentatively, and I may also be short-changing the gastropods (Gelperin 2013).

Earlier I discussed Feinberg and Mallatt’s view of sensing and consciousness (2016). In their full treatment, they distinguish several kinds of consciousness: exteroceptive, interoceptive, and affective (sometimes collapsing these into sensory and affective consciousness). They see instrumental learning as important on the affective side, and note the possible role of gastropods as richer on the affective than sensory side. But they group arthropods together as a single case, one probably showing all their varieties of consciousness. I think, instead, that arthropods might diverge in notable ways. Some marine crustaceans are long-lived and may have more “open” lives than arthropods on land. Adamo (2016), commenting on Klein and Barron’s claims for insect consciousness, also notes that insects tend to face selective pressure to reduce the size of their brains. A short-lived animal with little scope for flexible, open-ended behavior that is also under pressure to keep its brain small might keep its evaluative machinery simple – too simple for consciousness. Elwood’s work (discussed above) shows that evidence for pain is quite strong in some crustaceans – stronger than it is for insects, who have not, to my knowledge, been found to engage in behavioral trade-offs or wound-tending of the kind seen in crustaceans (Eisemann et al. 1984, Sneddon et al. 2014). On the other hand, instrumental learning has been found in insects of several kinds, including learning based on aversive stimuli (heat).

So at least in principle, we see several different path types that animals may have taken in the evolution of consciousness, as well as a significant chance of multiple path instances. A single path instance is only plausible if consciousness is very evolutionarily shallow, restricted to animals like us, or very deep, creeping into existence early in animal life, or even before.

1 Prinz also thinks that a kind of synchronized neural pattern, gamma waves, have special importance to consciousness – I won’t discuss that part of his view here.

2 I am indebted to Tyler Wilson for pressing this argument about learning to me. See also Shevlin (forthcoming) on the significance of motivational trade-offs.

Adamo SA (2016). Consciousness explained or consciousness redefined? Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 113(27): E3812.

Allen C (Chapter 38 in this volume). Associative learning.

Allen C, Fuchs P, Shriver A, and Wilson H (2005). Deciphering animal pain. In M Aydede (ed.), Pain: New Essays on Its Nature and the Methodology of Its Study. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, pp. 351–366.

Baars B (1988). A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker M, Wolanin P, and Stock J (2006). Signal transduction in bacterial chemotaxis. Bioessays 28: 9–22.

Barron AB, Søvik E, and Cornish JL (2010). The roles of dopamine and related compounds in rewardseeking behavior across animal phyla. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience 4: 1–9.

Budd G, and Jensen S (2015). The origin of the animals and a ‘Savannah’ hypothesis for early bilaterian evolution. Biological Reviews 92(1): 446–473, epub ahead of print. doi:10.1111/brv.12239

Burge T (2010). Origins of Objectivity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chalmers D. (1996). The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Crapse P, and Sommer M (2008). Corollary discharge across the animal kingdom. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9: 587–600.

Damasio A, and Carvalho G (2013). The nature of feelings: Evolutionary and neurobiological origins. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 14: 143–152.

Dehaene D. (2014). Consciousness and the Brain: Deciphering How the Brain Codes Our Thoughts. New York: Penguin Random House.

Denton D., McKinley MJ, Farrell M, and Egan DF (2009). The role of primordial emotions in the evolutionary origin of consciousness. Consciousness and Cognition 18: 500–514.

Eisemann, CH, Jorgensen WK, Merritt DJ, Rice MJ, Cribb BW, Webb PD, and Zalucki MP (1984). Do insects feel pain? – a biological view. Experientia 40: 164–167.

Elwood RW (2012). Evidence for pain in decapod crustaceans. Animal Welfare 21: 23–27.

Farris SM (2015). Evolution of brain elaboration. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 370: 20150054.

Feinberg T, and Mallatt J (2016). The Ancient Origins of Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gagliano M, Vyazovskiy V, Borbély A, Grimonprez M, and Depczynski M (2016). Learning by association in plants. Scientific Reports 6: 38427.

Gelperin A (2013). Associative memory mechanisms in terrestrial slugs and snails. In R Menzel and P Benjamin (eds.), Invertebrate Learning and Memory. London: Elsevier, pp. 280–290.

Ginsburg S, and Jablonka E (2007). The transition to experiencing: II. The evolution of associative learning based on feelings. Biological Theory 2: 231–243.

Godfrey-Smith P (2015). Integrated information. http://metazoan.net/27-integrated-information/

Godfrey-Smith P (forthcoming). Evolving across the explanatory gap.

Huigens ME, Pashalidou FG, Qian M-H, Bukovinszky T, Smid HM, van Loon JJA, Dicke M, and Fatouros NE (2009). Hitch-hiking parasitic wasp learns to exploit butterfly antiaphrodisiac. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 106: 820–825.

Jackson R, and Cross F (2011). Spider cognition. Advances in Insect Physiology 41: 115–174

Klein C, and Barron AB (2016). Insects have the capacity for subjective experience. Animal Sentience 9(1).

Merker B (2005). The liabilities of mobility: A selection pressure for the transition to consciousness in animal evolution. Consciousness and Cognition 14: 89–114.

Milner D, and Goodale M (2005). Sight Unseen: An Exploration of Conscious and Unconscious Vision. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Overgaard M, Rote J, Mouridsen K, and Ramsøy TZ (2006). Is conscious perception gradual or dichotomous? A comparison of report methodologies during a visual task. Consciousness and Cognition 15: 700–708.

Nagel T (1974). What is it like to be a bat? Philosophical Review 83: 435–450.

Nilsson D-E (2013). Eye evolution and its functional basis. Visual Neuroscience 30: 5–20.

Perry C, Barron A, and Cheng K (2013). Invertebrate learning and cognition: Relating phenomena to neural substrate. WIREs Cognitive Science 4: 561–582. doi:10.1002/wcs.1248

Peterson K, Cotton J, Gehling J, and Pisani D (2008). The Ediacaran emergence of bilaterians: Congruence between the genetic and the geological fossil records. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 363: 1435–1443.

Prinz J (Chapter 17 in this volume). Attention, working memory, and animal consciousness.

Shevlin H (forthcoming). Understanding suffering: A sensory-motivational account of unpleasant experience.

Sneddon L, Elwood RW, Adamo SA, and Leach MC (2014). Defining and assessing animal pain. Animal Behaviour 97: 201–212.

Tononi G, and Koch C (2015). Consciousness: Here, there and everywhere? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 370: 20140167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2014.0167

Trestman M (2013). The Cambrian explosion and the origins of embodied cognition. Biological Theory 8: 80–92.